Somatics, Healing, and Social Justice

Somatics, Healing, and Social Justice

Rationalism separates the self from the body, and the thinking or rational mind from the aliveness and experiences of the emotional and physical self. This philosophy moves us toward an objectifying view of the body and the physical world as parts—devoid of or separate from a person’s holistic and lived experience. This objectification, and mind-body split, have far-reaching consequences.

The rationalistic separation puts us at deep odds with ourselves. As we learn to dismiss our lived experience, to be rational instead of “too emotional,” we necessarily learn to numb, to dissociate, and to override the feelings of ourselves and others. This distancing truncates our ability to know what we deeply care about, how to relate within complexity, and how to feel and validate experiences—whether our own or those of another. Rationalism as a primary way of being tends to side with control when it comes to working skillfully with our biological/spiritual/social/psychological selves. The mind-body split reifies a particular power-over system as well.

We can consider who and what is associated with being rational—science, maleness, whiteness, education, and wealth—the “right people” to decide, advance, and rule. Consider also who and what is associated with body and feeling—sin, irrationality, emotions, “hysteria,” women, transgender, people of color, the exotic (read racist), indigenous, earth, desire—the “wrong” people to decide and lead. You can hear the multiple forms of oppression informing these and, in turn, how they are supported by rationalism.

We can consider who and what is associated with being rational—science, maleness, whiteness, education, and wealth—the “right people” to decide, advance, and rule. Consider also who and what is associated with body and feeling—sin, irrationality, emotions, “hysteria,” women, transgender, people of color, the exotic (read racist), indigenous, earth, desire—the “wrong” people to decide and lead. You can hear the multiple forms of oppression informing these and, in turn, how they are supported by rationalism.

This is not a vote dismissing rational thinking altogether or to rid us of science and scientific inquiry. Rather, it is to awaken to what is shaping us. What have been the costs of rationalism and who has repeatedly been thrown under the bus by its precepts? What of this do we want to question and change? What of rationalism as a cultural norm is deadening, disconnecting, or harmful?

The power-over economy will have us be consumers before people. Most anything we can think of to edit and manage the body is being sold to us—from a multibillion-dollar diet industry to chemicals to cover any smell. The traditional Church presents the body and human desires and sexuality as a sin. It is easier to control a person if you have made their inherent impulses toward life and contact shameful or punishable.

All over the place, from the popular culture to the propaganda system, there is constant pressure to make people feel that they are helpless, that the only role they can have is to ratify decisions and to consume. – Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent

A note about neuroscience and rationalism—there have been thousands of amazing findings within neuroscience over the last 20 years. In its current popularity, many people assume that because we can explain what happens in the brain, we understand behavior or how to change behavior. Many also interpret the brain as the most important organ—if we understand the brain, we understand humans. There are many organs without which we cannot live, like the heart, the lungs, and the large intestines. Interpretations of modern neuroscience can get caught in the same rationalistic tradition of objectifying the body as now merely carrying around the more important brain. It can also promote the idea that mental understanding alone lets us know how to change.

A note about neuroscience and rationalism—there have been thousands of amazing findings within neuroscience over the last 20 years. In its current popularity, many people assume that because we can explain what happens in the brain, we understand behavior or how to change behavior. Many also interpret the brain as the most important organ—if we understand the brain, we understand humans. There are many organs without which we cannot live, like the heart, the lungs, and the large intestines. Interpretations of modern neuroscience can get caught in the same rationalistic tradition of objectifying the body as now merely carrying around the more important brain. It can also promote the idea that mental understanding alone lets us know how to change.

We like to think of the brain as this incredible computing device, that’s designed for creativity and actualizing our purpose. The brain’s primary function is to keep you breathing, keep you alive, and keep you safe. It evolved in order to predict danger, to predict threat…. We need to hijack that machinery, and apply it in a deliberate and specific way. The good news is that your brain is a highly plastic device…. We have planning and imagination. Practices to engage the neuroplasticity will truly rewire your brain and its ability to function, so that you are set in alignment with purpose. – Andrew Huberman, neuroscientist and tenured professor in the Department of Neurobiology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, Presence: Living and Working on Purpose (Webinar, Strozzi Institute, 2018)

A somatic understanding of the body/self is radically different. It holds the body, self, thinking, emotions, action, and relating as an interconnected whole.

We, this human organism, have evolved for over three billion years. That’s a long, long time, from a human point of view. We have many capacities that we inherit through this evolutionary history, through having a human body, and many we can learn and cultivate. Listed below is an amazing range of our human capacities. Asking us to deny or compartmentalize aspects of being full humans can leave us longing for our humanity. The human organism, body/self has:

● Emotions: Inherent and foundational experiences that hold deep meaning for us. We can develop our emotional skills over a lifetime.

● Sensing and interpreting: We do this through our sense organs and through feeling. We sense ourselves, others, our environments, and the mystery (Spirit).

● Thinking, analysis, and the cultivation of critical thinking through learning and study.

● Touch and capacity to develop skilled touch: Touch is an inherent aspect of healing and bonding.

● Relating: We are social animals. We can develop our skills of relating over a lifetime. Much of how we relate is based on our own experiences of safety, belonging, and dignity—both personal and social—and the social, economic, and cultural systems we live within.

● Resilience: We have inherent resilience, and we can cultivate it.

● Presence: We have inherent presence, and we can cultivate it.

● Action: We can take action in many ways—from having conversations, to coordinating with others, to physical actions.

● Communication and language: Being exposed to and learning language is essential to our brain development. We can learn new languages throughout our lifetimes.

● Spirit: We can see this as consciousness or an animating force. This is interpreted in many ways across culture and time.

Somatics is not just an effective and potent set of tools by which to heal and transform deeply. It is also an invitation to mend a profound personal and social mind-body split, which has consequences that are more harmful than life affirming. I posit that returning or reintegrating into the life of our bodies allows us to return to a greater connection with each other, life, and land. It is a practice to help us de-objectify life. It lets us sense and feel life more readily.

All Photo-Art, Efes Kitap

From The Politics of Trauma: Somatics, Healing, and Social Justice by Staci K. Haines, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2019 by Staci K. Haines. Reprinted by permission of publisher.

About Staci K. Haines

Staci K. Haines is the co-founder of Generative Somatics, a multiracial social justice organization bringing somatics to social and environmental justice leaders, organizations, and alliances. She is the author of The Politics of Trauma: Somatics, Healing, and Social Justice.

What is Solidarity?

What is Solidarity?

I was born when all I once feared, I could love.

– Hazrat Bibi Rabia of Basra, 7th century Sufi saint

Survival has become an economizing on life. The civilization of collective survival increases dead time in individual lives to the point where the forces of death threaten to overwhelm collective survival itself. Unless, that is, the passion for destruction is replaced by the passion for life.

– Raoul Vaneigem, The Revolution of Everyday Life

One of the great crises of our times is the crisis of meaning, which is both a symptom and a cause of the broader polycrisis – the convergence of ecological, political, spiritual and social breakdown. Traditionally held certainties about humanity’s place in the world are crumbling. Those to whom we have abdicated our power – politicians, academics, doctors, experts, leaders – reflect back the confused, muddled buffoonery of a collective emperor with no clothes. Extinction illness and other psychological collateral effects are deepening both depression and denial, forcing humility and exacerbating hubris. The Anthropocene casts a long and convoluted shadow.

As the political adage goes, “we are prisoners of context in the absence of meaning.” So what then shall we do? A starting place is better understanding of and relating to the current context – i.e. assessing the nature and texture of the oxygen we breathe (even when we can’t). We can also attribute new and ancient meaning to the consequences of our actions. In this essay I argue that solidarity can play a central role in triangulating these two practices as a means towards sense-making. We can re-imagine solidarity as a communal, spiritual act. Solidarity as becoming.

Etymologically, solidarity comes from the Latin word solidus, a unit of account in ancient Rome. It then merged into French to become solidaire referring to interdependence, and then into English, in which its current definition is an agreement between, and support for, a group, an individual, an idea. It is essentially a bond of unity or agreement between people united around common cause. True to its original meaning, there is the notion of accountability at its core.

Below are some reflections on solidarity within the fast-changing context of modernity, or more aptly, the Kali Yuga, the dark ages prophesied by the Vedic traditions of India. I offer these five interlocking premises in the spirit of wondering aloud and fostering allyship. I do not claim any special expertise or moral authority. Like all truths, these are subjective notions anchored in a particular historical moment, through the medium of a biased individual (accompanied by a complex of seen and unseen forces such as ancestors), and an entangled set of antecedents bringing together the past, present and future simultaneously.

Solidarity is not something activists do. It is a requirement of being a citizen of our times.

It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.

– Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene

Most of us were not taught moral philosophy outside the constructs of our institutional religions or educational systems. I would like to propose a simple, time-tested applied ethic to steer our conversation. In the troubled times we find ourselves in, our disposition should be to side with those that have less power. In the context of capitalist modernity, to borrow Abdullah Öcalan’s language, this means siding with the oppressed, the exploited, the immiserate, the marginalized, the poor.

You can examine any situation, in all its complexity, and assess the following: who has more power over the other? Who is benefitting from the other’s misery? Who is exerting domination? Where does this power come from? What are the rights of those involved? From this vantage point of critical thinking, one can then engage their moral will in support of balancing power. This can be applied to both the human and more-than-human realms of other species and animate ecosystems.

This ethic does not mean you are the judge or arbiter of final say; rather, it is a heuristic, a short-hand assessment for where to pledge your moral weight and your solidarity. Of course, the difficulty is that we are subjective beings with pre-existing identities and implicit biases. And our identities matter and impact who and how we are able to show up for others in society. Solidarity requires the cultivation of wisdom and discernment, strategy and compassion.

Sometimes being an ally to those in adverse power dynamics may mean educating the oppressor by interrupting their consciousness and steering them towards awareness of equity through relationship and commitment to their higher being. More often, solidarity requires being an accomplice rather than an ally; it requires a direct affront to power itself.

Part of our responsibility is to understand the construct of our identities. Not to transcend or bypass them, but rather, to situate our beingness (our race, gender, socio-economic status, cognitive biases, etc.) in the broader context of society in order to be in deeper kinship with others. By engaging in a perspective outside of our internalized role-type, we create the ability to disidentify, at least momentarily, with our social personas in order to be in service to others who are affected by the cultural constructs imposed on them.

However, our work of seeing and understanding the landscape and internal ley lines of intersecting identities, and the cultural byproducts they produce, does not stop here. In addition to our own inner deconstruction, we must also avail ourselves to perceiving and understanding the intersecting matrix of others – especially those who embody different histories and diverse backgrounds.

Perhaps by activating the lens of power, rendering meaning to the plight of other beings, human and otherwise, and being committed to see whole selves with multiple, intersecting identities, we can start to develop the critical capacity of moral judgement and discernment, not as something to fear, or something that others will do (e.g. activists), but rather as a requirement of being a citizen of our times.

Part of the reason we are in a crisis of meaning is that we have stopped exercising our meaning-making sensibilities – our dedication to what we deem so worthy of care that we would challenge anything, including our own constructed roles within the social hierarchy.

To become a citizen of our times requires that we understand the impoverishment of our times.

I don’t know who discovered water, but I can tell you it wasn’t a fish.

– Marshall McCluhan

We spend inordinate amounts of time consuming “culture”, yet we do not necessarily have the means to cultivate a critique of culture. Max Weber believed that the human is an animal suspended in webs of significance that we ourselves have spun. Indeed, culture is the cumulation of all those webs of significance. It is only by unveiling the threads that we can start to grasp the limitations of our perceived reality in the attempt to expand the horizon of possibility.

For those of us who live within the dominant culture of the West, our context often prevents us from understanding the consequences of our way of living. We are infantilized when it comes to basic knowledge like how money is created, where our waste goes, where our energy and resources are extracted from, where and how our food is grown, the history of our nations, and the origins of our sources of wealth.

On one level, this is an artifact of power. Privilege is a constraint. In fact, privilege is a blinding constraint. We appear to be hapless fish swimming in the ocean of neoliberal capitalism that impedes our ability to see selfishness masquerading as efficiency; destruction, war and violence wrapped in the euphemisms of economic growth and jobs; colonization masked as “development”; patriarchy obfuscated by pointing to the exceptions; structural racism occluded by “pull yourself up by your bootstraps”.

For one to understand power, one has to understand culture. In order to decode culture, one must develop critical faculties. To be critical, one must disidentify with the object of critique, in our case, the dominant culture.

This requires a de-colonization of one’s entire being. It is an ongoing praxis of deprogramming old constructs of greed, selfishness, short-termism, extraction, commodification, usury, disconnection, numbing and other life-denying tendencies. And reprogramming our mind-soul-heart-body complex with intrinsic values such as interdependence, altruism, generosity, cooperation, empathy, non-violence and solidarity with all life.

These are not programs to be swapped out or software upgrades to a computer. The mechanistic metaphors of Newtonian physics do not easily transfer to the messy reality of lived experience. These values are nurtured by entraining new beliefs, enacting new behaviors, contracting new relationships, activating new neural patterns in the brain, reordering new somatic responses in the body. And by “new”, I mean new as a subjective reference. In many ways, these are acts of remembering.

How does this apply to a politics of solidarity in practical terms? Every time we focus on a single issue that matters to us (e.g. lower corporate taxes, mandatory vaccinations, elite pedapholia rings, etc.) without examining the larger machinations of power or the interests we ally ourselves with (i.e. associational politics), we remove the possibility of true structural change. Every time we defend capitalism as a source of innovation or the “best-worst system” we have, we dishonor the 8000 species that go extinct every year and the majority of humanity that are suffering under the yoke of growth-based imperialism. Every time we say that some poverty will always exist, we condemn our fellow humans because of our own ignorance. Every time we say that we have the world we have because of human nature, we are amputating human ingenuity, connection, empathy and possibility.

We first need to understand the cultural waters we are swimming in before and during the process of forming and reforming our political perspectives. And we must deeply question any opinions we may hold that require the world to stay the way it is, especially if we are benefitting from the current order.

Solidarity is not a concept; it is an active, embodied practice

To define another being as an inert or passive object is to deny its ability to actively engage us and to provoke our senses; we thus block our perceptual reciprocity with that being. By linguistically defining the surrounding world as a determinate set of objects, we cut our conscious, speaking selves off from the spontaneous life of our sensing bodies.

– David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous

As we deepen our critique of the dominant culture, we will naturally start to oppose the values that are rewarded by our current order. By better understanding what we stand against, we will deepen our understanding of what we stand for. As we create intimacy with ideas such as solidarity, empathy, interdependence and other post-capitalist values, we refine our internal world, the felt experience of what it is to be a self-reflective, communitarian being in service to life. As we shift internally, we will find the external world of consensus reality start to mirror back these values, and in turn, our bodies will reflect the external changes.

The political transmutates into the somatic whether we are conscious of it or not. We carry the scars of history in our bodies, physically, genetically, epi-genetically and memetically. Solidarity requires that we honor history, that we do not deny or ignore the historical circumstances that led us to this moment. Techno-utopianism and the New Optimist agenda of people like Bill Gates and Stephen Pinker require amnesia and anesthesia, forgetting and numbing, as their starting place. The somatic realities of historical trauma and current life trauma, as they relate to different and intersecting social locations, presents an opportunity to redefine solidarity by engaging in relationships that actively heal the present while healing the past.

Although identities are political, they are not fixed; rather, they are emergent and ever-unfolding facets of human nature as a sub-stratum of cultural evolution. Intersectionality asks us to relate to a matrix of identities infinite in expression and limitless in nature. Rather than checking the boxes of understanding and political correctness, we are instead asked to develop our muscles of multi-faceted perception; we are asked to become more agile in our relational being and to develop a multitude of entry points to our empathy. Intersectionality challenges us to become humble in our orientation to solidarity because it requires us to question deep assumptions of our socialization. As the feminist scholar and poet Audre Lorde reminds us “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” We are tasked with developing a field of solidarity worthy of the complex forms humanity is dreaming itself into.

As we start to become practitioners of solidarity, we might find that our humanity expands as our conceptions of identity expand. We might find that we are more resilient in the face of the onslaught of neoliberalism and its seductive forces. We may find ourselves less susceptible to advertising propaganda or conspiracy theories on the one hand, or existential angst, despair and ennui on the other. We may find ourselves more adept at holding multiple simultaneous truths, ambiguity, apparent chaos and other paradoxes. We may find that solidarity as embodied practice is where true meaning and integrity comes from.

As we start to see how all oppression is connected, we can also start to see glimpses of how all healing is connected. And that our own liberation is not only bound up with that of others but that our collective future is dependent on it.

Solidarity is not an act of charity, rather it is a means of making us whole again. Solidarity will ask of us what charity never can.

Solidarity is a pathway to spiritual development

The world is perfect as it is, including my desire to change it.

– Ram Dass

It is a common belief that there is an oppositional relationship between inner work and outer work, spirituality and politics. They are separate domains – politics happens in halls of power or the streets, and spirituality happens in ashrams, churches, temples, forests, caves and other places of worship. This separation is often manifested in statements such as “I have to take care of myself before I can help others”. Although there is some truth in this sentiment, it overlooks the possibility that being in service to others is being in service to one’s self. The act of solidarity for another being or community of beings feeds the soul and cultivates character in ways that often cannot happen through traditional spiritual practices.

It is a common belief that there is an oppositional relationship between inner work and outer work, spirituality and politics. They are separate domains – politics happens in halls of power or the streets, and spirituality happens in ashrams, churches, temples, forests, caves and other places of worship. This separation is often manifested in statements such as “I have to take care of myself before I can help others”. Although there is some truth in this sentiment, it overlooks the possibility that being in service to others is being in service to one’s self. The act of solidarity for another being or community of beings feeds the soul and cultivates character in ways that often cannot happen through traditional spiritual practices.

The binary thinking goes both ways. Political communities often lack deeper spiritual practices and metaphysical worldviews beyond Cartesian rationalism. Activists often get burned out because they lack spiritual resourcing and a sustained depth of purpose. On the other hand, spiritual communities are often disconnected from reality as they attempt to bypass the physical plane. Through solidarity, there is the possibility of a sacred activism that creates lasting structural change.

For example, by engaging in collective prayer as an act of solidarity, we are exerting our life-force for shared healing, knowing and trusting that our healing is entangled with the healing of all others. Our individual healing can be a consequence of our prayer, but to focus our prayers on simply our own safety, abundance, etc. is to relegate our relationship with the divine into a selfish monologue.

Often, collective prayer or contemplation can become an entry point into a more thoughtful, delicate activism. Even for those deeply steeped in direct action and political organizing, transforming reactionary impulses such as outrage into intentional prayer opens latent potentialities. By spending time in contemplation about what another being may be going through, we access the possibility to live many lives, to see many perspectives, to hear many tongues, to know many ancestors, to receive the blessings of many deities. In that sense, empathy and solidarity are gateways to what quantum physicists call non-locality.

Solidarity expands our capacity for generosity, pleasure and grief

Generosity is doing justice without requiring justice.

– Imam Junaid of Bhagdad, 9th century Islamic scholar

Among activists, there has historically been a strong culture of self-flagellation, worldly denial and asceticism. This has partly contributed to a political climate bereft of pleasure, especially on the Left. This in turn repels potential allies and diminishes the appeal of social justice movements. To paraphrase Emma Goldman, a revolution without joy is not a revolution worth having. Nor will our subconscious ratify its manifestations. Part of the practice of resistance to dominant culture is to create and live alternatives of such beauty and extraordinariness that the so-called “others” are magnetically drawn to post-capitalist possibilities.

The more we develop our capacity for pleasure, the more we can access the immediacy of the present moment. The skill of being present with what is while creating what could be also allows us to access the deep grief that comes with being a human in the Anthropocene and potentiates the generosity of spirit that is required to flourish in these times.

As we remain present, as we hold what spiritual traditions call “witness consciousness” in the face of planetary destruction – of other species, of cultures and languages we will never know because of our way of living – we may also access the mythopoetic aspects of our being, the archetypal realms that can assist us in reshaping the physical world. We may start to remember that our lives are creative, shamanic acts we are performing on ourselves.

The practices of tending grief, of being faithful witness, of opening to pleasure, of deepening generosity, of expanding our circle of concern, can rewire our identities from atomized individuals having a personal experience to inter-relational beings taking part in the immensity of a self-generating cosmos.

As we shed the veils of separation and anthropocentric logic created by monocultures of the mind, we open ourselves to what the physicist David Bohm called the implicate order, an omnicentric worldview connected to the wholeness of every perceived other.

We are being prepared for even deeper complexity, breakdown, tragedy, renewal and rebirth. This transition calls upon all of us to be vigilant students of our cultures, to contemplate our entangled destinies, to abandon our entitlement, to transcend the apparent duality of inner and outer work, and to reaffirm our responsibility to each other and the interwoven fabric of our sentient planet and the living universe. Through solidarity we give more of ourselves over to the divine, to the collective unfolding, so the future can reflect back who we really are.

Special thanks to Carlin Quinn, Yael Marantz, Martin Kirk, Blessol Gathoni and Jason Hickel for their contributions. As with all acts of creation, this article was a communal endeavor.

About Alnoor Ladha

Alnoor Ladha is co-director of the Transition Resource Circle and co-author of the book Post Capitalist Philanthropy: Healing Wealth in the Time of Collapse.

Alnoor’s work focuses on the intersection of political organizing, systems thinking, structural change and narrative work. He was the co-founder and Executive Director of The Rules, a global network of activists, organizers, designers, coders, researchers, writers and others focused on changing the rules that create inequality, poverty and climate change.

CRAZYWISE | Shamanic Mysticism and Mental Wellness

CRAZYWISE | Shamanic Mysticism and Mental Wellness

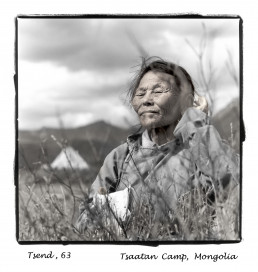

Cover Image | Sukulen, 37, Mt. Nyiru, Kenya

As a young girl, Sukulen began having dizzy spells and hearing voices. She said she was very frightened and thought she was getting ill. Her grandmother assured her that she was healthy and was, in fact, very gifted. Sukulen is now a highly respected “predictor” and healer in the Samburu tribe. Two months before I arrived, she had told several people in her village that I was coming and had described in detail my appearance and the equipment I was using.

For over twenty-five years Phil Borges has been documenting indigenous and tribal cultures. He often saw these cultures identify “psychotic” symptoms as an indicator of shamanic potential and was intrigued by how differently psychosis is defined and treated in the West.

For over twenty-five years Phil Borges has been documenting indigenous and tribal cultures. He often saw these cultures identify “psychotic” symptoms as an indicator of shamanic potential and was intrigued by how differently psychosis is defined and treated in the West.

Phil’s recent project, CRAZYWISE, explores the relevance of Shamanic traditional practices and beliefs to those of us living in the modern world. Through interviews with renowned mental health professionals including Gabor Mate, MD, Robert Whitaker, and Roshi Joan Halifax, PhD, Phil explores the growing severity of the mental health crisis in America and discovers a growing movement of professionals and psychiatric survivors who demand alternative treatments that focus on recovery, nurturing social connections, and finding meaning.

KOSMOS: You have shared wonderful portraits of shaman with the world. Your first experience with an altered state of consciousness as a cultural ritual was in Tibet?

PHIL: Yes, the State Oracle of Tibet, the Nechung Oracle is channeled through a Medium, called a Kuten and is the protector spirit of the Tibetan people. The Oracle is often consulted by the Dalai Lama on important issues. When I first met the Kuten in 1994 he was a 30-year-old monk named Thupten Ngodrup .

It was amazing to see this ceremony where he went into trance and spoke in an altered voice while the monks attending him wrote down everything he was saying. Then he lost consciousness and had to be carried out of the room. At first, I thought maybe this was a performance. To tell the truth, I just didn’t know what to think of it. However, two days later I got to interview the Kuten. He spoke little English, but I could tell, this young guy was sincere. He said, “when I’m in that state, I really don’t remember what I’m saying.” He loses himself entirely to this spirit entity that comes through him.

When we asked him how he became a Kuten he told us as a young monk he began to hear voices, had unusual mood swings, became sick and disoriented and thought he was dying. An older monk took him aside to tell him he had a special sensitivity and could be very useful to the Nechung Monastery and the Tibetan people.

KOSMOS: Very different experience than in our Western world! I’m sure, you have seen that a lot of these shamanic experiences follow similar patterns: hearing and seeing things that others can’t, being overcome by spirit, intense interest in the community about what the spirits are saying or doing.

PHIL: Yes, and I found it fascinating that they are often selected by the community for having what I always thought of as ‘a psychotic experience’ like hearing voices, having personality changes and mood swings. That interested me – what we consider “psychotic” symptoms was an indicator of shamanic potential! However, at the time, I didn’t know that twenty years later I would be making a film called CRAZYWISE that explored this further.

When I would go into a community to do a photoshoot for the UN, Amnesty International or an NGO, I’d ask “who are your healers, who are your visionaries?” And I started to hear this story over and over again – the way they were selected was most often a crisis. Once in a while it came down through a lineage like a son or daughter of a shaman would take over as a shaman. But, most of the time it was a crisis that identified the young initiate as having shamanic potential. Sometimes it was a physical crisis like a near fatal illness, but most often it was a mental/emotional crisis.

KOSMOS: Have you had any experiences you found it difficult to rationalize?

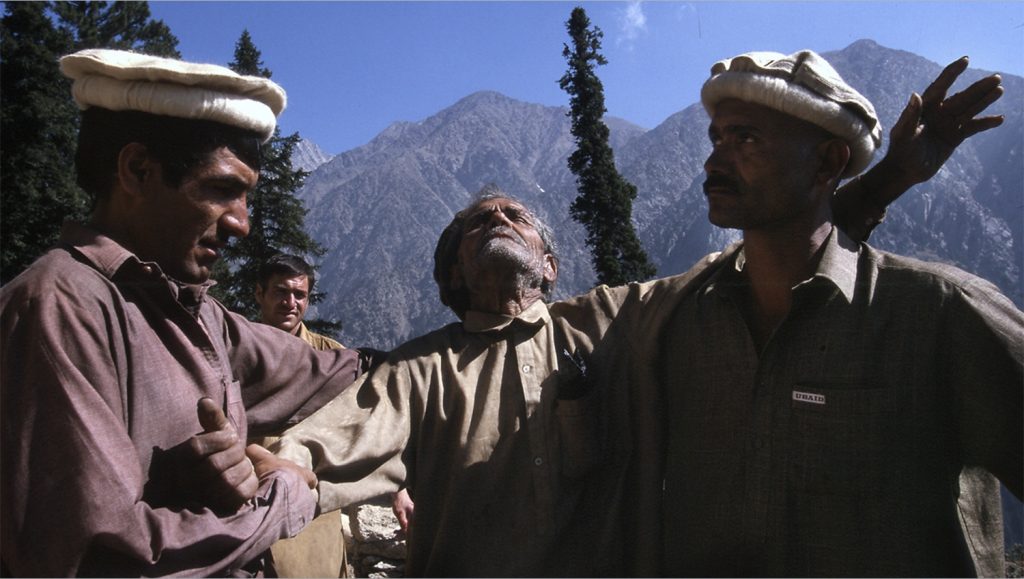

PHIL: I took my 16 year old son, Dax, on a trip to Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province to an area right on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan. There is a group of animists, the Kalash, who go back to the time of Alexander the Great, and have very different beliefs than the Islamic culture that surrounds them.

There were three shaman in the area and one of them was a goat herder who was considered to be the most powerful of the three. So Dax, our translator and I hiked up the mountain to his camp to visit him. His camp was right on the Afghan border and the shaman was a very talkative, outgoing 60 year-old man named Janduli Kahn. He said, “I want to do a ceremony for you in the morning to bless your journey.” I really didn’t want him to do it because he had to sacrifice one of his animals. They induce their trance by sacrificing an animal, then pouring the blood over burning Juniper branches and inhaling the smoke. I tried to talk him out of doing the ceremony but he insisted saying “you have traveled so far to get here I must do it.”

So, the next morning his sons started the fire, sacrificed the animal and caught their father as he fell backwards into a trance like state. A few moments later he came out of the trance, didn’t say a word and disappeared into his rock hut. We never saw him again. That was it.

So, the next morning his sons started the fire, sacrificed the animal and caught their father as he fell backwards into a trance like state. A few moments later he came out of the trance, didn’t say a word and disappeared into his rock hut. We never saw him again. That was it.

So I asked the sons, “What happened when he went into the trance? Did he say anything.”? And one of them told us his father said ‘our journey would be very difficult, but we would be safe’

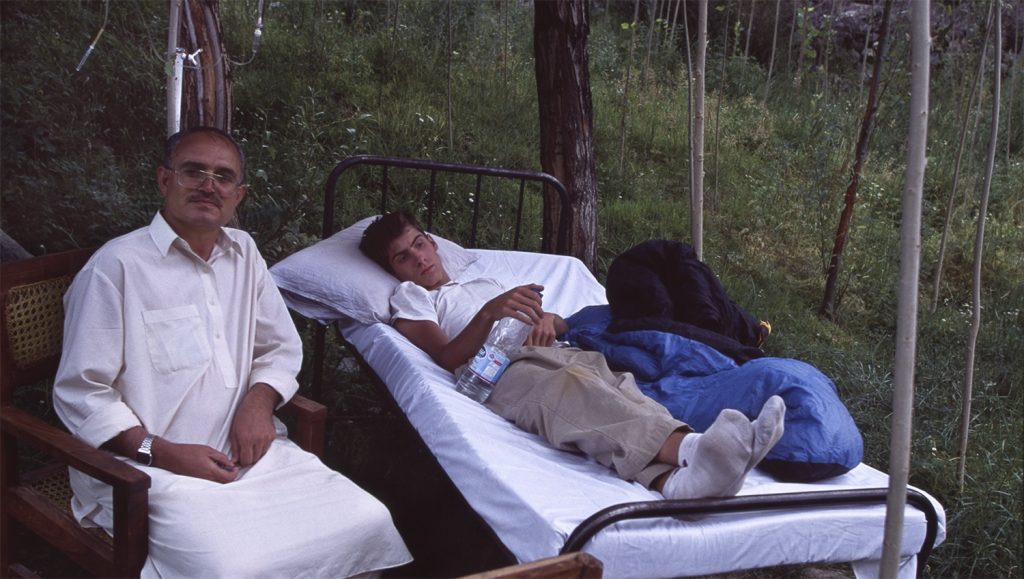

Dax became extremely ill over the next few days as we continued our journey into the remote Hindu Kush mountains. We were out in the middle of nowhere, literally. I mean, you would pass a shack every once in a while, and I was getting very worried. Dax couldn’t keep anything down and was very dehydrated and weak. He reached a point where he had a hard time sitting up and was slumped over.

I finally pulled off and set him under a shade tree because we had just passed a couple of little shacks. I was panicked!! I ran back and banged on the door of one … and a doctor from Islamabad who was visiting his mother answered the door! Wow. He had an IV drip with glucose and saline and set up a cot in their back yard where we rehydrated Dax. In two hours and he was fine. Unbelievable. I could not help hearing the words of the Kalash Shaman repeating in my head. (Interview continues below the Gallery)

I finally pulled off and set him under a shade tree because we had just passed a couple of little shacks. I was panicked!! I ran back and banged on the door of one … and a doctor from Islamabad who was visiting his mother answered the door! Wow. He had an IV drip with glucose and saline and set up a cot in their back yard where we rehydrated Dax. In two hours and he was fine. Unbelievable. I could not help hearing the words of the Kalash Shaman repeating in my head. (Interview continues below the Gallery)

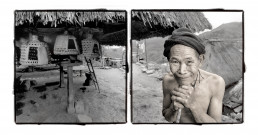

Namid 70 Tsagaannuur, Mongolia

Namid started her shamanic work when she was 14 years old. I watched in amazement as she spent a whole night beating her drum, sweating profusely, spinning wildly and repeatedly falling to the floor, calling on the mountain spirit to help a woman having trouble in pregnancy. She continued to see people the next morning who had come from miles away to seek her help. One by one, she gave them the money I had just given her for my lodging. She said, “if you want to live a long life, continue to help others.” (Darkhad)

Laya 81 Banaue, Philippines

Laya is a powerful Monbaki (shaman) in a mountain tribe called the Ifugao. When Laya was very young, his mother died and Tofong, the forest spirit, came to him shortly after. Today when Laya is treating a patient, he brings an offering into the forest for Tofong and shouts out the ill person’s name. If Tofong accepts the offering, Laya said the hair on the back of his neck will stand on end and he will feel the spirit enter his body – a good sign for the patient. The catholic church has recently lifted its ban on Ifugao rituals. (Ifugao)

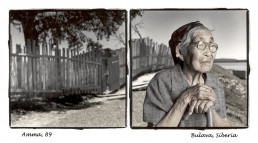

Amma 89 Bulava, Siberia

Amma had just completed an Ulchi ritual, called a kasa, for a neighbor who had died. She stayed up with the body for three days and nights while guiding the soul of the deceased to the “other world”, called Buni Village. She told me the kasa is very dangerous as the journey to Buni Village could cost her her life. Amma became a shaman rather late in life. She told me that she resisted the calling for many years because a shaman’s life is so hard. She said, “it’s not like a profession that you learn-it’s a calling one receives from the nature spirits.” (Ulchi)

Crazy…or wise?

The traditional wisdom of indigenous cultures often contradicts modern views about a mental health crisis. Is it a ‘calling’ to grow or just a ‘broken brain’? The documentary CRAZYWISE explores what can be learned from people around the world who have turned their psychological crisis into a positive transformative experience.

Watch the entire film at:

vimeo.com/ondemand/crazywise

KOSMOS: We don’t yet have the capacity in our culture to explain these non-ordinary experiences or states of being. We chalk them up to coincidence or magical thinking. But something deeper seems to be going on and we have a lot of catching up to do. When did you decide to make the film?

PHIL: One evening a friend of mine and I got to talking about making a short film on meditation. And the second or third person she sent to talk with me was Adam, who is featured in the film.

When Adam was 20, he had a psychotic episode and was immediately taken to a psychiatrist and put on a whole medication routine. And it went very badly for him. He was on 15 pills a day and having horrible side effects. So he stopped all his medication at once and did a 10 day silent meditation retreat, meditating 10 to 14 hours per day. I’ve since learned this is a very dangerous thing to do but it worked for Adam and he was able to go back to his job at a Whole Foods grocery store. I thought his story was very interesting, so I decided to start interviewing him every 2 to 3 weeks. He continued doing the meditation retreats until his fourth retreat when issues of a childhood molestation came up for him. He was quite upset but the retreat leaders were unable to handle that type of a problem and sent him home. When he told his parents that his grandfather had molested him they didn’t believe it.

Consequently he was rejected by his main pillars of support– his parents and the meditation community. It was shocking to see how fast he spiraled down after that happened. I mean, he was a healthy, normal kid when I met him and within a couple of weeks after that he lost his job and became homeless. He even looked totally different!!

KOSMOS: I have seen this before, that what we call a psychotic episode can completely transform the person – even the way they look in some cases, the way they talk, their whole demeanor.

PHIL: Especially the way they talk. I delved into the neuroscience of this and it’s fascinating what is being discovered right now, actually. Anyway, Adam became the catalyst for the film, CRAZYWISE. The film does not seek to over-romanticize indigenous wisdom, or completely condemn Western treatment. Not every indigenous person who has a crisis becomes a shaman. And many individuals benefit from Western medications. However, I believe indigenous peoples’ acceptance of non-ordinary states of consciousness, along with the use of rituals and metaphor that form deep connections to nature, to each other, and to their ancestors, is something we can learn from.

The loss of ego that can come from a mental/emotional crisis is a spiritual experience. Absolutely is! And many who successfully navigate the experience without being frightened can emerge stronger with more purpose and compassion.

But that’s the key. Often when you come back and you tell the people who love you the most, – your parents or your lover, or your boss, or your best friends – about things you’ve experienced that they can’t relate to. They get frightened and you pick up on that. The person in this state is extra sensitive to colors, to sounds, all their senses are amped up. Somebody who’s turned up the volume on all their senses, can pick up those feelings coming from other people and it scares them.

One of the things I’ve heard over and over again is, any time there’s a sense of unease or fear coming from those who know them best–it can make them think, ‘Yeah, maybe I am crazy. Something’s wrong here’, when what they really need is unconditional love and acceptance.

KOSMOS: Maybe the same is true on a collective level, that as a species or at least as a society, we can’t transform our collective trauma without new ways of understanding and radical love. What is coming up for you when you think about the collective experience that we’re now going through?

PHIL: I’ve talked to hundreds of people that have gone through that on a personal level – transformation coming out of crisis. Again, if they successfully navigate it, they usually come out with a lot more compassion and a lot more empathy.

So, if it’s anything like a personal crisis, our collective crisis has to be framed correctly.

This is a breaking down of the old concepts and structures, from our use of fossil fuels to the way we see different humans and non-humans as ‘other’. This is the breaking down in preparation for a birth of a whole new way of seeing and being in the world. And, it can go very badly if it isn’t framed properly – as a breakthrough rather than breakdown.

Our collective psychological crisis can also be an opportunity for growth and potentially transformational, not a just a catastrophe without meaning.

About Phil Borges

Phil Borges, has been documenting indigenous cultures and striving to create an understanding of the challenges they face for over 25 years. For his program, Stirring the Fire, Phil produced and filmed several short films, capturing the stories of women heroes and the issues they face all over the world, both as solo projects and in collaboration with organizations such as UN Women and CARE. Phil has spoken at multiple TED talks; including TED in 2007, TEDxRainier in 2012 and TEDxUMKC in 2013 and hosted television documentaries for Discovery and National Geographic.

Recovering the Divine Feminine

Recovering the Divine Feminine

I would like to offer an archetypal overview of where and how the masculine and feminine archetypes—reflected in the image of a God or Goddess—became separated, and why this separation has led to such deep crisis in Western civilization. I am not speaking only of the pandemic, but the far greater challenge of climate change.

We live in a world that has been governed by the masculine archetype for some 2,500 years, without the feminine archetype to balance it, with no sacred marriage between them. As a result, world culture and the human psyche are now dangerously out of alignment with the Earth and the Cosmos. The Feminine stands for the soul, for the heart, for compassion and justice—the two primary values which protect and serve life. It is summed up in this statement by a Council of the Indigenous People of North America:

All Life is sacred. We come into Life as sacred beings. When we abuse the sacredness of Life we affect all Creation.

Through ignorance, hubris, and the belief that we could dominate nature to the advantage of our species alone, we have interfered so disastrously with the organism of the planet, that over the last 50 years, our growing numbers and our exploitation of its resources have brought about the destruction of 60 percent of all species. Today we are faced with a choice—a choice that will determine whether or not we survive as a species. Can we relinquish the false myth of growth, progress, and consumption we have been living by, and cease our ongoing assault on the life and resources of the planet? Or will we continue on the same senseless path of conquest and domination?

Two thousand years ago, this prophecy was recorded in the Fourth Gospel of the Essenes. This Gospel, and three others, were discovered by Edmund Szekely in the secret archives of the Vatican and translated from the Aramaic by him:

But there will come a day when the Son of Man will turn his face from his Earthly Mother and betray her, even denying his Mother and his birth right. Then shall he sell her into slavery, and her flesh shall be ravaged, her blood polluted, and her breath smothered; he will bring the fire of death into all the parts of her kingdom, and his hunger will devour all her gifts and leave in their place only a desert.

All these things he will do out of ignorance of the Law, and as a man dying slowly cannot smell his own stench, so will the Son of Man be blind to the truth: that as he plunders and ravages and destroys his Earthly Mother, so does he plunder and ravage and destroy himself. For he was born of his Earthly Mother, and he is one with her, and all that he does to his Mother even so does he do to himself.

Every word of this prophecy has come to pass. Believing ourselves to be separate from and above nature, we have grossly interfered with the harmony of the natural world and are bringing disease and possible extinction upon ourselves.

In order to transform our present view of reality we need to understand the ideas and beliefs that have created it. When did we lose the awareness that all life is sacred? Why did we lose the feminine archetype that connected us to nature?

Owing to the research that I and others have conducted over the last 40 years, we now know that in the Paleolithic and Neolithic eras, the principal deity worshiped was the Great Mother. In this forgotten cosmology, there was no Creator beyond creation. Creation emerged from the womb of the Great Mother. All species, including our own, were her children. Everything on Earth and in the Cosmos was connected through relationship with her.

Then, around 1,500 BC, there was a change so great that its repercussions are keenly felt in all aspects of Western civilization. This change was the replacement of the Great Mother by the Great Father. As the monotheistic Father, God brought creation into being as something separate and distant from Himself, so nature became split off from spirit and was no longer sacred. Simultaneously, the rise of powerful city states in the Middle East led to the creation of a succession of vast empires, territorial conquest, and war.

Although the architectural, artistic, and literary creations of these empires were extensive, the suffering created by them was also widespread. Millions of young men lost their lives to war and died in atrocious pain. Millions of women and children were killed, raped, or sold into slavery. Deep traumas were created in the collective psyche of humanity that are unhealed to this day. During millennia of war, we forgot about nature and our relationship with her. Gradually, we developed the idea that we were above nature, entitled to control and dominate her for the benefit of our species alone.

Another event contributed to the loss of the sacredness of nature—a forgotten event that also had a devastating effect on women and the planet.[1]

The Jewish people once worshiped both a Goddess and a God—a Queen and a King of Heaven—who together created the world. But in 621 BC, under a king called Josiah, a powerful group of priests called Deuteronomists took control of the First Temple in Jerusalem. They removed every trace of the Goddess Asherah, the Queen of Heaven, who was worshiped as the Holy Spirit[2] and Divine Wisdom, and also as the Tree of Life—a Tree that connected the invisible and visible worlds, and whose fruit was the gift of immortality. The shamanic rituals of the High Priest which had honoured and communed with the Queen of Heaven were replaced by new rituals based on obedience to Yahweh’s Law.[3]

But the Deuteronomists didn’t stop there. They also created the Myth of the Fall with its punishing God and its grim message of guilt, sin, suffering, and the banishment of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden.[4] They demoted the Goddess—whose title was Mother of All Living—into the human figure of Eve. They blamed Eve for the sin of disobedience that brought about the Fall and for bringing sin, suffering, and death into the world. Henceforth, all women would be contaminated by Eve’s sin and would have to be under men’s control lest they create further disasters. From it there developed the idea that the whole human race was tainted by original sin, punished for a primordial act of disobedience. The created world was no longer a manifestation of the Tree of Life but was viewed as contaminated by the Fall, no longer sacred. Woman’s long oppression, even persecution, stems directly from this myth. Her voice was silenced for millennia.

Yahweh was left as the sole transcendent Creator God; The Divine Feminine aspect of God was deleted from the image of deity. The only place where the concept of the sacred marriage survived was in the mystical Jewish tradition of Kabbalah, known as the Voice of the Dove.[5] The Divine Feminine was not only banished from Judaism, but also from Christianity which took its image of God from Judaism. Islam also had a sole male creator god. The end-result of this new polarizing cosmology was that life on earth was split off from the divine world; nature was split off from spirit. Men came to be identified with spirit and women with nature. Body was split off from mind and mind from soul. Sexuality was sinful. Woman’s only role was to obey and serve man and carry his seed. All this was a complete reversal of the earlier cosmology focused on the Great Mother.

There is one further factor that needs to be included in this story: the deliberate decision by the Roman Church to wipe out all trace of Jesus’ marriage to Mary Magdalene. Think what it would have meant for the development of Western civilization if the union of Jesus and Mary Magdalene had been celebrated by the Church founded in his name. Had their marriage been recognized and Jesus not turned into the celibate Son of God, Christianity would have had a totally different history without a celibate male priesthood and without the terrifying persecution of women in the witch trials that scarred Europe for five centuries. We might have been spared the disastrous association of sexuality with sin and the misogyny and mistrust of women that affects our culture to this day.

Because of this history, we have been on the wrong path for more than two thousand years, out of alignment with the Earth and the Cosmos. It has led us to this time of crisis and of awakening, and to the need for a new, yet very old story that tells us we are the life and breath of the Divine in human form and that all life is infused with Divinity.[6]

Materialist or reductionist science is built on the flawed foundation bequeathed to it by patriarchal religion and has dispensed with both God and the soul. It tells us that the universe is without life, purpose, or meaning. When the physical brain dies, that is the end of us. The highest authority is the rational mind. We are separate from the world around us. The master story is technological progress and unlimited growth.

I think this explains why, in a worldwide culture influenced by the secular philosophy of science, we have come to believe that it doesn’t matter what we do to matter—that nature and matter are not sacred, that we are not part of that sacredness. This is why there is no foundation for morality in our relationship with the Earth. What we think we need, we take.

Jung could see the dangers of this materialist philosophy and commented:

As scientific understanding has grown, so our world has become dehumanized. Man feels himself isolated in the cosmos, because he is no longer involved in nature and has lost his emotional “unconscious identity” with natural phenomena… No voices now speak to man from stones, plants, and animals, nor does he speak to them believing they can hear. His contact with nature has gone.[7]

Once, long ago, the world was experienced as alive with spirit. Nature was part of a sacred cosmic whole. In spite of horrendous persecution, Indigenous peoples of the world have kept alive this awareness of the sacredness of nature and the idea of our kinship with all creation.

The new story emerging in quantum physics tells us that the universe is a unified field. Our lives are part of a cosmic web of life which connects all life forms in the universe and on our planet. Every atom of life interacts with every other atom, no matter how distant. A new vision is struggling to be born—a vision of our relationship with an intelligent, living, and interconnected universe.

We are called to a profound process of transformation that is manifesting as a new planetary consciousness: a consciousness which recognizes that we are part of a Sacred Web of Life. We need a science and a technology that does not seek to dominate nature but works with nature, humbly respecting its harmonious order. We need women who truly embody the Feminine to guide us,[8] working with enlightened men, to restore the values and the practices that can transform our relationship with the planet into one of love and care.

This pandemic carries an urgent message for us to wake up to the small window of opportunity we have to change course before it’s too late. This means change in every sphere of life: change in the very concept of what it means to be human and living on this extraordinary planet—change above all, in our relationship with the Divine Feminine. We tread a path which is on the knife-edge between the conscious integration of a new vision on the one hand, and the virtual extinction of our species on the other. Which path will we choose?

This essay is derived from a talk given for Humanity Rising, August 11, 2020

[1] See Betty Kovacs, Merchants of Light (Claremont: The Kamlak Center, 2019)

[2] This loss of the Holy Spirit was repeated at the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE when the Hebrew feminine noun for the Holy Spirit—ruach—was translated first into the Greek word pneuma which is genderless, and then into the Latin spiritus sanctus which is masculine. The Christian Trinity was rendered entirely masculine and the former feminine gender of the Holy Spirit was permanently lost to Christianity.

[3] The books of the Old Testament Scholar, Margaret Barker, give the facts of this story in detail.

[4] Genesis 2 & 3

[5] See Anne Baring, The Dream of the Cosmos, rev. ed. (UK: Archive Publishing, 2020), chapter 3.

[6] See my talks on Hinduism, Buddhism, Daoism, and Christianity on www.annebaring.com.

[7] Carl G. Jung, Man and His Symbols (New York: Random House, 1986), p. 95

[8] By this, I mean women who are not taken over by the will to power.

About Anne Baring

Anne Baring b. 1931. MA Oxon. PhD in Wisdom Studies, Ubiquity University 2018. Jungian Analyst, author and co-author of 7 books including, with Jules Cashford, The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image; with Andrew Harvey, The Mystic Vision and The Divine Feminine; with Dr. Scilla Elworthy, Soul Power: an Agenda for a Conscious Humanity. Her most recent book, The Dream of the Cosmos: A Quest for the Soul (2013, updated and reprinted 2020), was awarded the Scientific and Medical Network Book Prize for 2013. The ground of all her work is a deep interest in the spiritual, mythological, shamanic, and artistic traditions of different cultures. Her website is devoted to the affirmation of a new vision of reality and the issues facing us at this crucial time of choice. www.annebaring.com

An Evolutionary Transition Is Coming—Are You Ready?

An Evolutionary Transition Is Coming—Are You Ready?

“This is the greatest discovery of the scientific enterprise: You take hydrogen gas, and you leave it alone, and it turns into rosebushes, giraffes, and humans.”

The famous line from cosmologist Brian Swimme is striking because it transcends the frameworks and categories which we place over the continuum of life and reveals that, when all is said and done, the universe is not a noun, but a verb: a single miraculous process of becoming.

People find it hard to conceptualise cosmological, biological, and cultural evolution as one process. But when we take the tightly compartmentalised domains of scientific knowledge, bundle them together, roll them out like pastry, and take a big step back, a few patterns and trajectories, which are consistent throughout all those successive levels of evolution—from the Big Bang to the present moment—immediately become visible.

For one—the universe started in absolute simplicity and has evolved toward complexity. From hydrogen, atoms formed the heavier elements; from atoms emerged molecules; from simple prokaryote cells came more complex eukaryote cells; from eukaryote cells came multicellular organisms.

Another—as evolution has progressed, the scales of cooperative organisation have got larger. When life first emerged on this planet, it was at the scale of a millionth of a metre. But single-celled organisms cooperated to form multicellular organisms, and multicellular organisms cooperated to form groups of multicellular organisms such as shoals of fish, beehives, and packs of dogs. The trajectory was recapitulated in human evolution—bands cooperated to form tribes, tribes to form chieftainships, chieftainships to form city states, and city states to form modern nation states. In global economic trade, although not yet in politics, cooperation now spans the entire planet.

But it’s the third trajectory which is most interesting for those who study change: evolutionary change is not linear, but telescopic. Evolution is, itself, evolving, acquiring new creative capacities, and accelerating. Put more simply, evolution is getting better at evolving.

The first major evolutionary transition was the emergence of life, kickstarting the process of biological evolution. Initially, all life was single-celled and reproduced asexually; that is, by simply copying the genetic material of one generation to produce the next. Other than occasional mistakes in the copying process, or mutations, each generation is genetically identical to the last. With such little variation between generations, evolution is painstakingly slow.

The second major evolutionary transition was the transition to sexual reproduction. Sexual reproduction is still biological evolution—it’s just biological evolution powered in a new way. Rather than blind copying, sexual reproduction works by mixing the genetic material of two different organisms together. Each offspring is, therefore, genetically unique: with far greater variation to go to work on, evolutionary change could occur orders of magnitude faster than it could via asexual reproduction, leading to a flourishing of diversity and complexity, and the evolution of the five major animal kingdoms.

The transition to human cultural evolution represented a more fundamental shift. Cultural evolution is still variation and selection at work, but this time we’re talking about the variation and selection of ideas or memes, as opposed to the variation and selection of genes.

Take a new recipe for example: let’s say I write a new recipe for a cheesecake and post it online. If the recipe is good, people will use it, recommend it to their friends, and it will spread. Next, let’s suppose someone comes up with an improvement. Then the two variants of the recipe will compete with each other, and whichever recipe is tastier is likely to spread more widely, and the less tasty variant is more likely to die out. That is variation and selection at work, pure and simple.

Languages, businesses, technologies, religions, fashion, music, even something as abstract as systems of governance, all undergo variation and selection, and, just like our genes, they jostle and compete to drive our behaviour.

The key advantage of cultural evolution is that adaptive information is transmitted from organism to organism horizontally via language, as opposed to biological evolution where it’s carried in our DNA and inherited vertically over generations. If we’re mentally flexible enough, we can change our behaviour the moment we receive new information; this gives humans their evolutionary edge. As evolutionary psychologist Steven C. Hayes wrote: “‘survival of the most adaptable’ is far truer to the whole of evolutionary data than the hoary phrase ‘survival of the fittest.'” Thus, while it took over four billion years of biological evolution for insects and birds to evolve the capacity to fly, through cultural evolution humans developed manned flight after only 50,000 years.

Notice also how there’s a layering effect—just as sexual reproduction did not bring an end to asexual reproduction, cultural evolution did not bring an end to biological evolution. They’re more like new pathways through which the evolutionary process can unfurl. Much like removing progressively larger and larger rocks from a dam, evolutionary transitions allow the rapids of change to flow more powerfully than they could before.

And so while stars and planets are still forming over aeons of cosmological evolution out there in space, and biological evolution is trundling along over millennia under the sea and in the forests, the human race is being catapulted forward with every passing decade of cultural evolution as our tools, technologies, and societies get more and more complex. What begins as a drop, turns into a trickle, and ends as a torrent.

Now the floodgates are about to open. We are on the cusp of another great evolutionary transition. Just as sexual reproduction turbocharged the biological evolutionary process, Conscious Evolution is about to turbocharge the cultural evolutionary process.

When Darwin published On the Origin of Species, a critical feedback loop was connected: evolution became conscious of itself. Much like an individual undergoing a spiritual awakening, the evolutionary process has, through us, awoke to itself.

And that self-awareness represents a huge evolutionary leap forward. As any therapist will tell you, the first step toward changing your patterns of behaviour is to become aware of them. What unconscious triggers cause you to get angry or reach for another glass of wine? If you can become truly self-aware in those moments, then you have given yourself a choice. You’re no longer stuck in an automatic pattern of behaviour.

What I’m trying to describe here is analogous, except we’re talking about the self-awareness not of individuals, but of the evolutionary process as a whole. Because evolution, too, has its habits and patterns, and some of those are conducive to humanity’s evolutionary flourishing, while others are holding us back.

Take the human proclivity for sugar for example. Our taste for sugar has been shaped by millions of years of biological evolution in a hunter-gatherer context where sugar was rare, and a sweet tooth would have conferred a survival advantage.

But now that processed sugar is readily available, our taste for sugar is no longer a reliable guide to survival and reproductive success—it’s more like a reliable guide to diabetes.

The same goes for all sorts of human behaviours that have been shaped by our evolutionary past: the drive to accumulate wealth, status, and power; to hoard resources; and engage in in-group/out-group tribalism. These behaviours may have made evolutionary sense in a hunter-gatherer context where we lived in small groups, violence between groups was common, and natural resources were abundant. But in our radically altered modern context, many of those instincts and desires have become maladaptive—they no longer serve the evolutionary purpose they were intended for and, indeed, they may even be actively detrimental to our individual and collective chances of survival.

What we need is the ability to let all of that go, so that rather than unconsciously playing out our biological conditioning, we become conscious architects of our individual and collective destinies.

Through the evolution of human consciousness, cultural evolution has the potential to move from being a largely unconscious process pushed forward by our biological conditioning to a fully conscious process pulled forward by our visions of a better future. By coming to understand the process in which we’re embedded, by extrapolating those trajectories I’ve described into the future, we can tack more closely to the wind, charting a path which is aligned with the arrow of evolution.

If, as a species, we can successfully make the transition to Conscious Evolution, not only will we dramatically increase our chances of survival, but we will be stepping into a story which can provide meaning and purpose for humanity’s existence.

As the developmental psychologist Abraham Maslow pointed out, finding meaning and purpose is a very real human need; when left unfulfilled, people suffer.

The role of helping people find meaning and purpose used to be met squarely by religion. But after the historical Enlightenment and the Age of Reason, many people began to realise that in their more archaic forms, the great mythic religions don’t stand up to rational scrutiny. And in its place we are left with a science which, for all its explanatory power in telling us how the world works, has almost nothing to say about how we should live in it.

And so today many people find themselves without a story that can point to their place and purpose in the universe, and yet can withstand the test of rational scrutiny.

And that’s what Conscious Evolution is. It’s the new story that we’ve been waiting for.

It’s a story about where we’ve come from, who we are, and where we might go.

It says loudly and clearly that our choices matter, that the evolutionary process is not just a meaningless random walk, but that it’s actually going somewhere and humanity can be a part of that if we choose to.

It calls us to stand at the apex of a 13.8 billion-year-old process, a process which will continue long after we die, and invites us to pull it forward in our own unique way—to become free, creative, and conscious participants in the thrust of evolution.

As the great evolutionary philosopher Teilhard de Chardin wrote:

“At once humbled and ennobled by our discoveries, we are gradually coming to see ourselves as a part of vast and continuing processes; as though awakening from a dream, we are beginning to realize that our nobility consists in serving, like intelligent atoms, the work proceeding in the Universe. We have discovered that there is a Whole, of which we are the elements. We have found the world in our own souls.”

The only question is: are you ready to play your part?

***

The Conscious Evolution Podcast is out now on Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

About Robert Cobbold

Robert Cobbold is a philosopher, educator, and public speaker who has delivered transformative educational experiences to over 40,000 young people worldwide. He is founding editor of Conscious Evolution, an online publication and podcast aiming to disseminate the evolutionary worldview, and kindle an evolutionary transition, and CEO of Native.

We The "Peoples" | The UN at 75

Throughout the ages, humanity has been advancing on a winding path towards higher degrees of maturity. The well-being of humankind is not static; it requires ever greater degrees of commitment to fulfilling ever increasing ambitions. At each stage, even significant advances may prove inadequate. And it is in these moments of great crisis when humanity is called on, by virtue of the prevailing circumstances, to reconsider its trajectory. Largely, though not exclusively, driven by enormous tragedy, these moments are significant in the narrative of human progress. They become key markers, elements of our unfolding story—though, their historical import may be difficult to discern at the time. Few could have predicted, for instance, the extent and effect of either of the World Wars at their outset—yet the duration and depth of both tragedies gave rise to new conceptions of global governance, as seen in the emergence of the League of Nations and United Nations, respectively.

At this, the 75th Anniversary of the United Nations, the world is seeing yet another collective tragedy unfolding in COVID-19, its effects analogous to that of a war, though of a different form. And many predict that it presages additional global calamities. Like previous historic inflection points, a robust dialogue on the future of humanity is needed. The People’s Declaration and Program for Global Action adopted at the UN75 People’s Forum in May is one contribution to this necessary global discourse. Completed before the Declaration to be adopted by world leaders later this month, it offers an approach to the global problems we face that goes beyond the confines of political boundaries. Speaking in the voice of “we the peoples”, it analyzes the reality of the world in which we live, articulates the needs of humanity in light of that reality, and lays out a process by which those needs can be met. It turns to the UN in its current form as a starting point for further iteration, but challenges some of the underlying assumptions which, although helpful at the inception of the UN, have shown their limitations in light of present circumstances.

The People’s Declaration was put together through a process of collecting perspectives from a wide range of voices around the world and identifying points of convergence at the highest level of consensus. Recognizing that “progress depends on universal participation” and that “the advance of one leads to the advance of all,” by harmonizing our diverse perspectives we hope to help humanity walk a path towards greater flourishing.

The hope is that significant change at this time of profound transition can be ushered in without comparable degrees of suffering. Through a lively and growing discussion, we hope to articulate a compelling vision for humanity, one that describes a destiny in which our highest aspirations find expression. While the great sacrifices that led to the League of Nations and the United Nations can be measured in the immense loss of life, let us commit to bringing about a more just and equal world through only the loss of outworn ideas and narrow self-interest.

THE WAY FORWARD

In order to advance a conversation on the future of humanity, there are certain necessary preconditions. First, and most importantly, we must acknowledge that we do not have a system for global governance suited to today’s needs and that we do not know what that system will look like. Logically, this leads to acknowledging a second point: humanity’s interconnectedness, oneness and, accordingly, our shared destiny. This is what distinguishes the modern era from any time that preceded it.

Third, certain values in pursuit of equality and dignity must increasingly guide our behavior: the search for truth, trustworthiness, justice, honesty, integrity, to list a few. Finally, as consensus around these three points is consolidated, substantive dialogue and experimentation around new arrangements of governance can take place.

Specific reforms have been presented time and again, but they often meet resistance—often for reasons of territorial sovereignty. By looking at areas of the UN where the ceding of sovereignty has produced useful results (e.g. technical bodies like the International Telecommunication Union and the International Civil Aviation Organization), similar measures could help serve to strengthen the hand of those trying to enact reforms of the peace and security architecture, or the climate and environmental institutions. More dramatic ideas, like a global tax body, a standing reserve force, or a World Parliament would be well served by further discussion and the broadening of consensus. This  historic UN anniversary, coincident with the unfortunate nexus of cascading global crises, lends an opportunity for sustained deliberations about the next steps in humanity’s efforts towards just governance at all levels.

historic UN anniversary, coincident with the unfortunate nexus of cascading global crises, lends an opportunity for sustained deliberations about the next steps in humanity’s efforts towards just governance at all levels.

Ultimately, humanity requires a global structure that is as integrated and comprehensive as the global realities it faces. While its implementation may seem out of reach at the moment, as Nelson Mandela famously said, “it always seems impossible, until it’s done.” So let’s get to work.

About Daniel Perell

Daniel Perell joined the Baha’i International Community’s United Nations Office as a Representative in 2011. His areas of work include social and sustainable development, global citizenship, human rights, the role of religion in society, and defense of the Baha’i Community. He is currently a Global Organizing Partner of the NGO Major Group and the Chair of the NGO Committee for Social Development.

Venerating the Sacred | Art as Cultural Therapy

Venerating the Sacred | Art as Cultural Therapy

Featured Image: Puma Concolor Coryi | The Florida Panther

A reserved, stealthy predator of enormous physical grace and power, the Florida panther is one of the most majestic large felines in the wild. While jaguars roamed as far east as Louisiana, and pumas were widespread from the East to the West coasts, today the Florida panther is the only large feline remaining in the Southeast. Once found throughout the southeast United States, the Florida panther now is critically endangered, occupying only a small area of South Florida, about 5 percent of its former range, and it numbers just 100 to 120 individual cats. Source: Center for Biological Diversity

Artist’s Statement

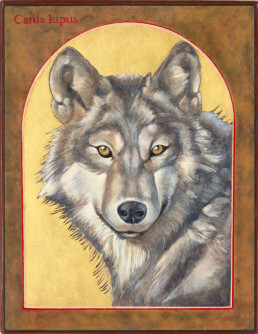

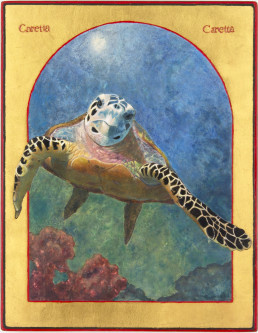

Icons— those ancient paintings we see in museums and Christian Orthodox Churches— expressions in symbolic form of the teachings of the saints, ascetics and leaders of the Church throughout the centuries. In the Orthodox tradition, they are considered scripture in images and “windows to the Divine.” Their function, through their contemplation, is to draw us closer and connect us to the numinous world behind all phenomena.

I have been a practitioner of this ancient art form for nearly thirty years. I experience it as a joy and a transformative experience. While the iconographer is creating these prescribed images on the icon board, s/he is is steeped in these ancient teachings. The flow of the pigments, working with gold leaf, are in themselves healing.

Soon into my practice however, as an informal student of the great geologian Thomas Berry, I couldn’t help but feel that something profound was missing from this venerable tradition.

It was the anthropocentrism which felt increasingly confining to me, where nature is consigned to the backdrop for the human drama and our journey to an intimate, creative relationship with the Divine.

The problem as I saw it was that things were backwards: The Book of Nature is primary; it comes before written Scripture. Watching the Natural World unravel before me, and seeing humanity’s utter disregard for the Earth itself, with exceptions of course, I felt it was time to expand this tradition to include the Natural World.

Hence my ongoing project of contemporary icons, Sacred Icons of Threatened and Endangered Species. Each image is made with the same method and materials in creating traditional iconographic images. Like the traditional images, they are meant to be contemplated in order to experience the divine origin of these other-than-human beings.

These works are a form of Cultural Therapy, needed in order to transform our behavior toward Nature, from a use relationship to one of communion and caring. In addition to the aim of changing consciousness, this project transforms contemplation into action. Fifty percent of the sale of each work benefits the Center for Biological Diversity, an organization that fights tirelessly to secure a future for all creatures great and small.

If I could sum up the spirit behind my work, it is expressed in this passage from Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica,