Baptism of Fire

I heard the knock in the engine just after I saw the road sign. It said, “Manning—50 kilometers.” It bothered me—the knock—because it wouldn’t stop, and because, other than knowing how to put in gas and oil, I knew nothing about car engines. I was on a long, lonely stretch of road in northern Alberta, driving from Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories to Edmonton. And I didn’t want to get out of the car.

It was a beautiful winter morning. But two days before, there had been a huge dump of snow. During the night, the plows had left eight-foot drifts on the side of the road. It must have thawed for a while, and when the temperature began to plunge, it coated everything—the trees, the road signs, and the telephone poles—in a surreal world of ice. I’d been creeping along the highway for miles, peeking out from under my visor to protect my eyes from the glaring sun, trying to keep the car from drifting into the snow banks. It was like driving on an ice rink. And now the engine was complaining, and I didn’t want to get out of the car because it was something like -35 and still going down. And I didn’t know anything about engines.

I pulled over in the shadow of the snow embankment, popped the hood, and looked in at the engine, hoping that the problem was going to be easy to fix, like some wire or something hanging down from the side of the engine that you just had to plug back in. Or better still, maybe some off duty auto mechanic would be passing by, see me looking under the hood, park in front of me, and walk up to me and say, “Need any help?”—which wasn’t too likely since I hadn’t seen another vehicle on the road for the last half hour.

Just as I was reaching over the engine to wiggle some mysterious part that seemed to be vibrating, I heard something behind me. I turned around. There was a snowshoe sitting right in the middle of the road. I looked around trying to figure out where it had come from. Then, as I watched, another one flew in an arc from the other side of the piled up snow. It hit the centre of the road and skidded upside down to the other side. This was followed a moment later by a head, a body, arms, and legs that suddenly appeared at the top of the embankment, teetered unsteadily for a moment, and came slithering down onto the road. I watched as he picked himself up and began to brush himself off.

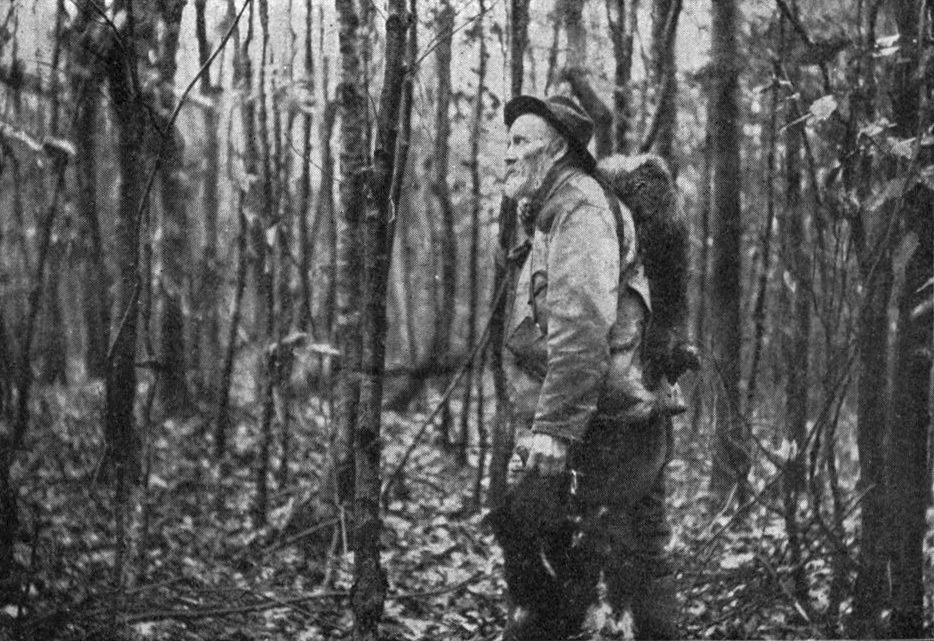

He was a gaunt looking character, tall and thin. He had one of those long brown greatcoats like you see the defeated German troops wearing in the films as they retreat from Stalingrad. He had a sort of pilot hat with padded ear flaps, white arctic boots, and a rucksack on his back. I could only guess at his age. But he looked quite old. It was hard to tell how old because he was in disguise. Icicles hung from his eyebrow, his mustache, his long thick beard, and even from his shoulder-length hair that poked out from under his cap. He had worked up a real sweat pounding through the bush. When he shook his head to clear the snow, the icicles seemed to tinkle together like a soft wind through glass wind chimes.

He looked at me and nodded, showing no great surprise at landing almost on top of me and my car in such a remote location. He then looked up and down the road in both directions, turned back to me, and said, “Could use a ride.”

“Sure,” I said, “where you going?”

”Manning.”

“You don’t know anything about cars, do you?” I asked.

“Not really,” he said. He glanced at the engine block but didn‘t show a great deal of interest. Just shook his head.

So I closed the hood. He went to retrieve his snowshoes, threw them into the back seat along with the rucksack, and clambered into the passenger seat beside me. I could see his knees were up around his chin, so I reached under the front of his seat for the lever and pushed the seat back as far as it would go. Then we started off, crawling along the icy road in the glaring sunlight.

For a while he didn’t say anything. As he started to thaw, he took a rag out of his pocket, took his cap off, and started mopping his face and head. A bit of steam rose from the top of his head. “Sounds like you’re trying to throw a piston,” he said. I nodded knowingly.

“Is there a garage or a dealer in Manning?” I asked.

“What kind of car is this?” His eyes were looking around the dashboard for an insignia.

“A Volvo,“ I said, “an old Volvo.”

“I don’t think you’ll get any help in Manning,” he said. “Nobody knows anything about foreign cars. You’ll probably have to go on to The Peace.”

“The Peace?”

“Peace River,” he said.

“Oh, do you think I’ll make it?”

“You might,” he said without too much conviction in his voice.

More silence.

I was holding the car in the middle of the road, trying to keep it from sliding off to the side. He was using the warmth of his hand to melt the frost on the side window so he could look out at the scenery.

“What were you doing in the bush?” I asked.

“Checking my trap line.”

“Tell me about trapping up here,” I said.

So he did. He talked in a sort of rough way with a slight French-Canadian accent, but he seemed fairly well educated or at least knowledgeable about his business. He discussed the life of the trapper; the decline in prices (“You can’t make a living at it anymore.”); the lifestyle; the “goddamned anti-fur lobby”; the problems with the new Connibear trap; the “damned government that put in this superhighway” that destroyed the wilderness and forced him to move his cabin further back into the bush; global warming and the dangers it causes: “Not nearly as cold as it used to get in the old days, and you take your life in your hands trying to cross rivers and lakes in the winter.”

“How’d you get into it?” I asked.

“My father was a trapper,” he said. “It sort of came naturally. When I came back from W-W-1,” he pronounced each letter separately, “there wasn’t much else I could do.”

“What branch of the armed forces were you in?” I asked.

“What?” He looked at me. “Hearing ain’t good no more.”

I raised my voice, “Were you in the army?”

“Yeah, I was a grunt. A foot-slogger.”

“Did you see action?” I asked.

“Yep. For three whole days…and, for two and a half days, I was flat on my back.”

Puzzled, I looked over at him. He was clearing the spot on the window. It had begun to frost over again. Lousy Volvo heater.

“They shipped me over to France to a battle called Vimy Ridge. I just got into the trenches where my battalion was stationed, and we got the signal to go ‘over the top.’ I got about twenty yards, was climbing over some barbed wire, and got hit in the leg. The guys behind me just mashed me down as they ran right over top of me. They left me behind. Then they clambered all over me again as they came running back…and then the Germans, right behind them, they mashed me down. It went on like that for about two days—first one side taking the ground, then the other side taking it back. I kept getting stepped on but didn’t say a word because, in the lull between charges, the snipers were just sitting back taking pot shots at anything that moved in the other guy’s uniform. It was the worst at night. You’d hear some poor devil stuck in the barbed wire yelling for help. They’d send up a flare, and the machine guns would start pounding away, raking the barbed wire. For two whole days I lay there looking up at the sky. If guys weren’t walking on me, they were zipping bullets around me.”

He paused, pulled out a pouch of tobacco, and began rolling a cigarette by hand. Halfway through he asked, “Do you mind?”

“No,” I said.

“Want one?”

I shook my head. He rolled the tobacco back and forth on the paper in his palm. He licked the paper, sealed the tobacco in, and then ran his fingers down the length of the cigarette a few times to straighten it. He put it in his mouth, lit it with a wooden match from a small box he kept in his breast pocket, took a long drag, and gently exhaled the smoke against the windshield.

“Anyway,” he continued, “they found me a few hours after the last charge, still hanging there, passed out from the pain. A dog sniffed me out—one of our dogs. They pumped in the morphine, and I ended up in hospital. A few days after I got there, I remember a general coming to visit the ward I was in. He asked me where I was from and how I ‘got it.’ I told him. He said to me, ‘Son, you had a real baptism of fire, didn’t you?’ I said, ‘Yes, Sir,’ but I didn’t know what he meant by that ‘baptism of fire’ thing. Later someone told me it meant I had made it. I was a real soldier because of what I had been through. Anyway, they gave me a medal and shipped me home. My leg got better, or almost better, but my mind wasn’t right for a long time. One of those army head doctors in Edmonton told me to do something that wouldn’t take too much thinking. So I came back here and began to work my father’s old line.”

“Ever have a family?” I asked.

“Yep. Had a wife and two boys. She was Chip.”

“Chip?”

“Chipewyan. She was a Chipewyan from northern Manitoba. I’m a Metis from Paddle Prairie up north. You passed by it on the way down. She died about twenty years ago.”

I nodded, as if remembering passing his community.

“Don’t know where the boys are now. Might have died. One of them was in the Navy and used to send me a bit of tobacco money in the mail from time to time—but I haven’t heard from him for a long time. In the early days, the wife and I used to listen to the CBC every Friday night, and they would pass on messages to people in the bush. We were hoping to get a message from the boys. But we never did. Can’t blame them really for not staying in touch. I was strange in the head when they were young and used to get drunk from time to time.” He took a final drag on his cigarette and stubbed it out in the ashtray.

“What about you?” he said.

“Me?”

“Yeah, tell me about you.”

“Okay, but first a pit stop.” We got out of the car and stood a few yards apart drilling yellow holes into the embankment. It now had to be about -40, and the engine sounded as bad on the outside as it did on the inside. We hopped back into the car, shared some coffee I had in a thermos, and started up again.

“I was born in Toronto, spent a dozen years or so in a monastery, and worked as a priest in New York and Baltimore doing a lot of social work types of things in inner cities. Then I lived in Paris for a while working as a student chaplain during the student riots in the spring of 1968. Then ended up in the States, left the priesthood, and worked with hippies and drug addicts in Milwaukee for about five years.”

“What kind of priest?“ he said.

“Roman Catholic.”

“You couldn’t get married, right?”

“That’s right.”

“It ain’t natural,” he said.

“Yeah, I know. That’s one of the reasons I left. So, I met my wife, we got married, and we’ve had three children—two boys and a girl. My wife’s a school teacher.”

“What do you do now?” he asked.

“I work mostly with native groups, in Inuit and Dene communities around the North, helping them set up programs and services—that kind of thing.”

“Do you still do priest things?” he said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Do you still work as a priest?”

“No, not really.”

“But you still know things—about God and death and stuff.”

“Yeah, I guess.”

He turned back to the window, and, for a couple of minutes, he scraped the frost on the edge of his spy hole with his fingernail, making it a bit larger. We drove in silence just listening to the sound of the tires and the knock in the engine. After a while, he looked over at me and said, “What happens to babies when they die early? Where do they go?”

“What do you mean?”

He paused, and I sensed that he was struggling for words, wondering how to tell me something.

“We had three kids,” he said, “there was a baby girl.”

I nodded to show him I was listening carefully.

“It was January and it was cold like this—only it stayed -40 to -50 for about six weeks. We were in our cabin way back in the bush, and my wife was waiting to have a baby. One night there was a storm. Some wolves came in and got to our dogs—killed my leader and another dog, tore up some of the others before I managed to get out and chase them off. But we were stranded and couldn’t get into town. We were running short on supplies, and my wife had the baby, a girl baby. It was tough for her giving birth, but not nearly as tough as afterwards. The baby wouldn’t eat. My wife kept trying to force her onto the breast. But she didn’t seem to have the strength to suck. My wife kept trying, kept putting the tit in her mouth, but the baby just couldn’t seem to do it. At night, my wife would lie in bed on her back with the baby on top of her, hoping she would suck—but she wouldn’t, and my wife would cry all night long. By the third night, she was exhausted and she fell asleep for a while. When she woke up, the baby was dead. My wife cried for a while—but I think she was all cried out. She just wrapped the baby in a blanket so the boys wouldn’t know what happened. We only had the one big room, but she didn’t want them to know just yet. So she just turned against the wall with the baby up along side her next to the wall.”

“That afternoon, I sat on the edge of the bed and talked to her. She was still lying with her face to the wall, protecting the baby. I told her we had to do something with the baby—but we couldn’t let the creatures get her.”

“Creatures?”

“Creatures—you know, the wolves and foxes and ravens. There were creatures all around our place. We couldn’t bury her because the ground was too hard, and if we just put her in the snow, the creatures would surely dig her out.”

“That night, after the boys went to sleep, I took the baby from my wife and put her in a burlap bag. I wet the bag a bit to dampen it down and tied the top with a pink ribbon my wife had been saving just in case it was a girl. I lifted the top on the stove and lowered the bag down into the flames. I remember looking over at my wife. She was sitting on a bench in front of the stove. The room was pretty dark, but I could see her face in the light from the flames. She was just looking right ahead, no tears, nothing. She was just staring at the stove with a very sad look on her face.”

“We sat together on the bench for a long time afterwards, but she didn’t say anything. In the morning, when the boys asked about the baby, we told them that she had gone up to heaven with God. But my wife knew that’s not what happened.”

“What do you mean?” I was a bit puzzled.

“My wife said that when she was a girl, the priest had told her mom that if a baby died without being baptized, she wouldn’t go to heaven. She’d go to some other place. And my wife couldn’t get that out of her mind. She blamed herself for what happened to the baby. And she never got over it. She was different after that. I don’t remember her ever laughing any more. She was always sad, and she never said very much. And we didn’t live together as a man and wife, if you know what I mean. I mean she wouldn’t let me touch her in that way—you know. We stayed together for fifteen years, until after the boys had gone, and then she died.”

I nodded, and we sat in silence for a while. My chest started to pound a bit faster. He looked over at me. I knew what was coming.

“Was she right?”

“What do you mean?” I said.

“About the place—did she go to that other place like the priest said…because she wasn’t baptized by the priest?”

I thought for a moment. “No,” I said.

“Then where is she?”

“She’s in heaven with your wife.”

He looked at me a bit puzzled.

“She had a different kind of baptism,” I said, “the kind you had in the army.”

He looked straight out the window ahead. I sensed the tension draining out of his body, and a calmness came over him as if a mystery had finally been cleared up. We both sat quietly watching the scenery go by until I dropped him outside the post office in Manning. He got out and gathered his snowshoes and rucksack from the back seat. I got out to say goodbye. We shook hands.

“Did we do the right thing, I mean with the stove and all?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “You did the right thing.”

He looked down at the ground. “Good luck with that piston,” he said. He smiled at me and turned. I watched him climb the stairs with the snowshoes over his shoulder and disappear though the double doors.