Worldviews Conjured by Words

featured photo | Pixabay

Originating from profound antique cosmologies—composed of chirping birds, murmuring springs, thundering skies, and echoing mountain ranges—an assembly of sounds informs human languages with meaning in naming and identifying things in the world around us; describing and defining sensations, relationships, and codes of conduct; understanding and expressing complex realities of time and space; and so much more. All of this is bundled into utterances that strive to verbally convey our very existence and lived experiences.

A significant component of shaping our worldviews resides not only within our cultural stories but also within the very words and the language we hear and speak. Questions stir within me as I make my way through the Tongass forest with my Tlingit friends:

Where are the Earth-honoring words in our minds and upon our tongues in the dominant culture? Where is the language that animates the land and inherently connects us to place, a living Earth, and an alive, story-filled landscape? Is there any chance that the poetry of our living Earth can still be heard, hidden fugitive-like in the ancestral tongues of the dominant culture? How can we support the leadership of Indigenous Peoples who are working to protect and revive their languages that carry invaluable knowledge, and which are hanging by a thin strand due to the relentless assault of colonization?

I have always been fascinated by words. Not just their meanings, but their etymology—a word’s origin and development. But my interest reaches further into a word’s actual sound and how it affects our senses and how the word-sound connects us to our antecedents, who formed speech to transmit what is choreographed in the mind.

As many of us learned in high school physics class, sound is produced by waves, passing through air or water in the form of vibrations that most of us can hear with our ears and feel with our bodies. But science alone cannot account for the magical conjuring that transforms sound waves into declarations of poetic “amore” or fiery calls to action that raise our adrenaline; or recitations of wisdom that ring true in our inner knowing; or eloquent prayers and incantations that alter our very consciousness; or the distinct and familiar voices of loved ones that thrill our hearts and make them flutter.

As many of us learned in high school physics class, sound is produced by waves, passing through air or water in the form of vibrations that most of us can hear with our ears and feel with our bodies. But science alone cannot account for the magical conjuring that transforms sound waves into declarations of poetic “amore” or fiery calls to action that raise our adrenaline; or recitations of wisdom that ring true in our inner knowing; or eloquent prayers and incantations that alter our very consciousness; or the distinct and familiar voices of loved ones that thrill our hearts and make them flutter.

By joining consonants and vowels, we can conjure concepts, actions, realms of existence, mystical imaginings, and a surfeit of emotions into existence. By spelling out words, whether using a written alphabet or a series of phonemes, we create communications that can influence our human experience and perceptions, from the intimacy of a meaningful exchange with a beloved to a visionary oration to the global community. While the ability to use language is a seemingly mundane, everyday experience, it is one of the most puissant agencies we have as humans—one that must be wielded with care, wisdom, and accountability. Language is foundational in influencing and informing our worldview and the way we imagine, experience, and actualize the world around us.

I am particularly interested in how we can redevelop an Earth-loving language that respects nature and the staggering and awe-inspiring reality of existence itself—a language that can hold the multivalent auspicious nature of our living Earth; a decolonized, anti-racist language of equity and care; a language whose very syntax and timbre convey the remarkable and ancient kin relationships within the web of life; a sumptuous, multidimensional language that those of us speaking modern languages can employ to share our histories, cosmologies, and traditions; a language of animacy and enchantment that can knit us to the land, grounding us to a specific place and opening our hearts and minds to the aliveness of the world and our love for nature.

Do we have access to words and languages that are life-enhancing, that awaken our consciousness to an animate Earth and our place in a living cosmology? Do the words we choose, and the order in which we string them together, depict the world as a web of sacred systems with agency, or instead, tragically, as a vault of commodities and dead-matter resources for human use?

Of course, evolving our language is not enough on its own to completely transform our worldviews or our actions toward the sacred land. Using words that convey a living Earth does not necessarily guarantee that speakers will respect the web of nature. That said, the vocabulary, syntax, and word meanings we use every day, out loud and in our minds, do, in the larger cultural context, shape the way we perceive the world, deepening the well-worn paths in our minds that reflect our cosmologies, societal assumptions, and values that ultimately affect our actions. Altering the way we communicate, and exploring new ways of conceptualizing and imagining, can forge new thought patterns and perceptions. Thus, part of making space for diverse worldviews, healing our relationship with nature, and finding new ways of being lies within the realm of language, memory, and a storied living landscape.

It is fortunate that the articulation of a multivalent Nature is brilliantly alive in hundreds of Indigenous languages around the world today, describing the natural world with powerful agency while also transferring invaluable wisdom of ecologies and land relationships through generations of memory.

Tragically, however, Indigenous languages are seriously threatened by the assault of modernity and colonization: in fact, many profound languages have already died, or are dying, due to the ongoing attack on Indigenous Peoples. And in this great offense, we cannot underestimate the truly devastating loss of worldviews and immense knowledge. As philosopher and polyglot George Steiner comments, “When a language dies, a possible world dies with it. … a language contains within itself the boundless potential of discovery, of recompositions of reality, of articulate dreams.” There has also been a significant loss of words and languages from older land-based times the world over. Noam Chomsky points out, “Some of the most dramatic language loss is in Europe. If you go back a century in Europe, all over the place people were speaking different languages.”

Indigenous author and teacher Martín Prechtel recounts one of his many experiences with language in his book The Disobedience of the Daughter of the Sun, offering a particularly insightful look at the verbs many Indigenous languages use and the need to keep this knowledge alive. He grew up speaking a refined Indigenous language on a reservation in New Mexico and later spoke Tz’utujil and other intricate Mayan dialects while living in Guatemala. Within this context, he makes the distinct point that none of those ancient, complex languages possesses the verb “to be.”

For those of us whose first language is English or another Indo-European language, it can be difficult to imagine a conversation without “she is,” “they were,” or “it is.” The primary way to express ourselves without “to be” is through copious use of metaphors. But Prechtel tells us, “The brilliant ingenuity of Indigenous language and what is indigenous in all languages, especially the language of origination, ritual and sacred, though often mounted on rails of metaphor, is the way they zoom way past metaphor into realms of understanding that have metaphor looking rather naïve.” Speakers of non-to-be languages do use idioms for other purposes; however, in places where we would use a “to be” construction, they express that connection in ways that reflect their way of thinking about the world and, specifically, the relationships between beings living in the world.

The dependence of Indo-European languages on “to be” constructions also informs the way we interpret a culture’s rituals. An Indo-European speaker, for example, often will view an Indigenous ritual as a metaphor: this represents the universe; that represents the sun; this is a fertility symbol, and so on, instead of seeing that the universe is versus that it is being represented. Prechtel goes further to describe how the verb “to be” is the way English speakers normally express a connection between two entities. Indigenous and non-to-be languages can express these connections in ways that reflect—and shape—the speakers’ understanding of relationships. Prechtel shares an example from the Tz’utujil language, which uses the verbs “ruqan” and “ruxin.” Both are often incorrectly translated as “to be,” but in fact they mean “carries” and “belongs to”; for example, “Ruxin wa ja vinaq” literally means “It belongs to those people,” but an English speaker would say “That is how those people are.” If one were to translate “This is my land; this land is mine” into Tz’utujil, it would become “Javra uleu ruqan cavinnaq joj; ruxin joj ja uleu,” which literally means “This soil carries my people; we belong to this land.”

It requires extra attention for a speaker of a “to be” language to create a sense of belonging to a place and the precise nature of the relationship between humans and the land, and between beings and their attributes or states. While English speakers can also misrepresent a relationship using the verb “belong”—for example, “this land belongs to me,”—using a verb other than “to be” forces a speaker to stop and think of what they are saying.

On occasion I have experimented with phrasing where I grew up as “The coastal land of Mendocino carries me,” or “My family belongs to the land of Mendocino.” It might seem strange at first, but if I belong to the land of Mendocino, and its soil carries me, what then is my responsibility to the land, to other beings who live there, and to the original peoples of these lands?

Most Indigenous languages recognize non-human beings with agency as “persons” and express these relationships as sentient kin. In contrast, many Indo-European languages such as English are human-centric, and they tend to objectify the land and her natural systems, portraying them grammatically and lexically as non-animate beings without agency. Internalizing this kind of language and hearing it daily reinforces the dominant culture’s worldview of the other-than-human world as separate from and lower than humans, and therefore existing solely for human benefit.

Anishinaabe and Métis scholar Mary Isabelle Young, in her book Pimatisiwin: Walking in a Good Way, gives several examples of the way her language treats non-humans as living beings with a spirit. An Anishinaabe-speaking participant in Young’s project shared that the Anishinaabe language uses two suffixes to pluralize a noun: one for animate nouns and one for inanimate nouns. Trees and rocks are animate, living, so they take the same animate suffix used for humans and animals, while the inanimate suffix is reserved for non-living things such as dishes.

Similarly, in Mundari, a language spoken by the Munda peoples of northeast India, forces of nature such as wind, rain, and rivers are grammatically “animatized” when they appear as the subject in a sentence with a transitive verb—animacy is indicated by agreement elements affixed to the end of the verb, indicating that their agency is equal to that of humans, animals, deities, and the astral bodies.8 This is not surprising, given that the Munda peoples hold an animate cosmology worldview, and the Munda revere their deities, including the Mother Earth Goddess Chalapachho Devi, in sacred groves called sarna.

When I consider the kind of human beings we in the dominant culture need to become to live in a post-colonial context and navigate the Anthropocene, I realize our work is not only to support Indigenous-led efforts to revitalize and protect their languages, which is absolutely critical, but also to transform our own tongues into languages of belonging and kinship by learning to bend, circumvent, liberate, and stretch language that currently objectifies nature until we become speakers of languages that affirm a living universe. No doubt, this is a long-arc cultural transformation strategy, but one I think is necessary.

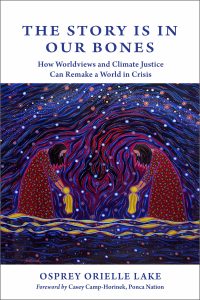

Excerpted with permission from New Society Publishers

The Story is in Our Bones: How Worldviews and Climate Justice Can Remake a World in Crisis

by Osprey Orielle Lake