Reflections on Outliving My Son

Warning: This article includes content related to the topic of suicide. If you or a loved one may be at risk, please click HERE.

It was a Saturday night when my son took his life, at the age of 27. Earlier that day, while Jon still had a functioning brain and body, he hurled three coatracks onto the floor. For months, he had been raging at us, his parents. He had no one else with whom to share an agony he couldn’t escape.

I wonder what he felt in his final moments: relief that his struggles and their futility would be over? Or did he just not care anymore? If it was oblivion that greeted him, did he finally get a break from bailing out a boat that was constantly filling through a hole the size of his human head?

My own life now lies scattered across the floor. But I know that the bridge between the breakdown of everything I thought I knew and the other shore that waits for me can only be crossed with a willingness to see Jon and myself anew.

I remember…As a teen, on a week-long trip to Mexico, he called asking us for permission to get a tattoo. We said no. He once made all the arrangements and traveled on his own to attend a gaming weekend in Atlanta. Jon was one of the best at “World of Warcraft”. He also drove to Durango, Colorado for his high school reunion. Jon had musical ability he didn’t pursue past adolescence, but he poured himself into academics In his last year of law school, he mentored other students on the Law Review, staying up late at night to answer their questions. He even wrote a forward to the Blue Book in an attempt to make its rules fathomable for his fellow law students.

But in his last months of life, he would walk around and around the block, trying to push back against his self-imposed incarceration in his bedroom.

Now, Jon’s phone rests beside our bed, kept alive on a charger, and we hear its beeps as messages bearing invitations from other gamers come in. That our socially-anxious son had a community of gaming friends should be good news, but it adds weight to the thought that he could have had a future if he had only waited another heartbeat or two.

Jon was just setting out, trying to find a place for himself so he could feel his value. Now, his broken dreams feel like those pieces of cardboard on street corners, with their faded words: “Please help me,” “Please see my pain,” “I don’t want to live like this.” Those scarcely uttered words didn’t penetrate me enough while he was alive. Now I wear them on my heart, so that when my heart learns to break, they will fall in.

Blame has no place on the path of grief: not for us, not for Jon, not for our world. What is needed now is understanding and forgiveness.

A 20-year-old picture I keep close by shows a younger version of me and a five-year-old Jon, his right arm in a green fiberglass cast – he had recently slipped off the jungle gym and broken his arm. What I see is the comfort of family, a home, and a backyard to play in.

We all had our lives to look forward to then. What went so wrong? How could Jon’s intelligence, his interests, his ability to master the demands of our educational system, all run aground just two decades later?

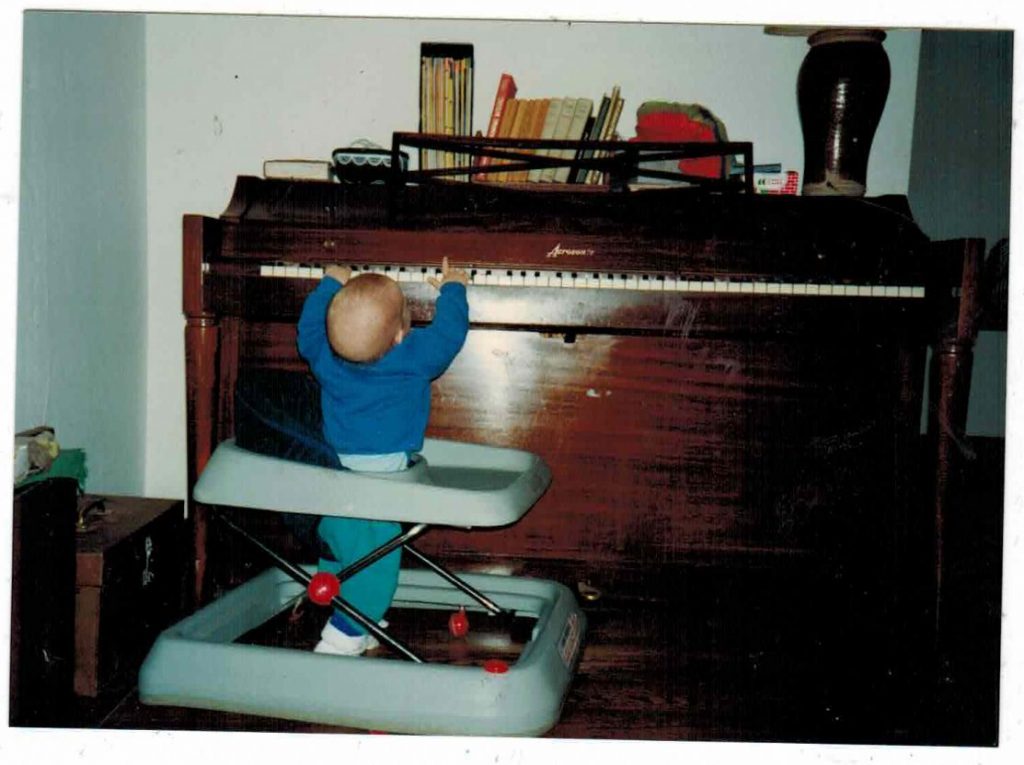

I have a photo of Jon, as a baby, reaching up to the keyboard and playing a deliberate melody. Years later, at a recital, when he played Beethoven’s “Fur Elise,” a man in the row ahead of us remarked to the woman beside him, “Finally, some real music!”

I have a photo of Jon, as a baby, reaching up to the keyboard and playing a deliberate melody. Years later, at a recital, when he played Beethoven’s “Fur Elise,” a man in the row ahead of us remarked to the woman beside him, “Finally, some real music!”

Thank God I couldn’t see then the future that awaited us. If I had known then that Jon would be swept from this world, how could I have had any hope myself?

This morning, feeling at ease, I wonder—if he ever looks my way– would Jon be glad that I sometimes am able to feel at home in the world? I don’t know if he is still hanging around; but I do remember how, even when his own distress threatened to consume him, he was always considerate of others.

What is a person to do when their world provides no juice for their soul?

What was Jon to do, after years of following the rules, working hard, being respectful, remembering birthdays, and wishing others a good day, when his own days were so rarely happy? What was he to do with the knowledge that his addiction and his obsessions were inflicting pain on the people closest to him? What was Jon to do?

Well, I know what he did. He stepped out of his own mind’s terrible regime.

As I take up the task of understanding Jon’s life and of valuing it, I need to decode a message that I believe he left me:

“This world is too sacred to leave in the hands of the lowest common denominator of fallen human nature, as we ransack Mother Earth and cast aside the lives of living beings every moment of the day and night; not only the lives of human beings such as Jon; not just the lives of all the creatures whose habitat we are destroying and whose daily bread has become imprisonment in foul cages—but future generations of all the species who call our planet home.”

A few months after Jon’s death, a therapist confronted me about my regrets, my guilt, and the horrible fear that if I had behaved differently Jon would still be alive. He told me that Jon had been trying to tell me something, but that I hadn’t heard him.

It took me until the next session before I was able to ask him what Jon had been trying to tell me.

“He was trying to tell you how much pain he was in.”

When I didn’t look away from the silence that opened up, he told me that I was now trying to rob Jon of his power to choose for himself how he lived and how he died.

I want to honor Jon’s power and his life, as I live the remainder of mine. And if Jon and I meet again one day, perhaps we will be able to look into each other’s souls and say, “Dear One, we both tried the best we knew how”.

These reflections are drawn from: ”Winter Came Early; Reflections on Outliving my Son” available HERE.

Dear Michael,

A beautifully written tribute to Jon. Your open heart doesn’t stray from the painful bits that this kind of learning requires. My takeaway was this sentence, “When I didn’t look away from the silence that opened up, he told me that I was now trying to rob Jon of his power to choose for himself how he lived and how he died.” Truly that is something that survivors can only do with the courage to face our fears of our own frail humanity. “Dear One, we both tried the best we knew how”.