Climate Crisis | A Problem of Myth?

A Unified Divine and Nature

The contemporary Western understanding of myth is that of Greco-Roman gods battling epic wars upon Mount Olympus. European stories of dragons and knights. Indigenous myths explaining the origins of the seasons and the Sun, of eagle and snake gods. We define myth as something imagined, it’s a story, it’s not real. But these myths were real, in that they explained the unexplainable. How else can a hunter-gatherer in 20000 BC explain the rising and falling of the sun, or the changing of the seasons, but to give it a story and thus a meaning? Myths have such power, become so widely accepted, that they define eras of spiritual and even scientific thought.

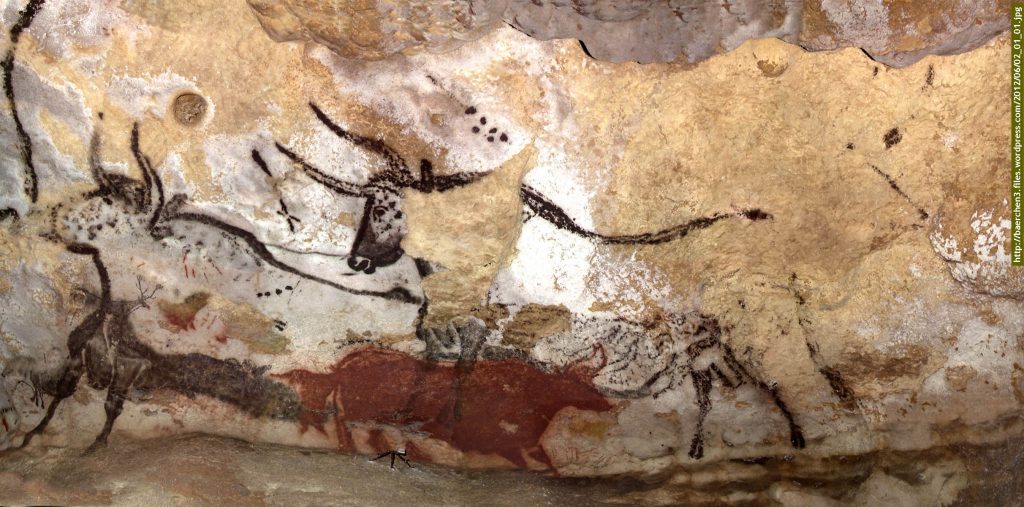

The earliest known myths personified the sky and the earth, animals and rocks, as willful, intelligent beings. At this point in myth history, the Divine and Nature are one force, not separate or siloed as we know them today. Karen Armstrong, an expert in myth, tells the story of hunter-gatherers roaming the plains of the world, deeply vulnerable to the weather cycles.

She argues that early humans created myth because life was rough, killing was emotionally painful, and they were at the whim of the elements. Thunder, floods and snowstorms were all supernatural phenomena that invoked awe and humility. Armstrong argues that myth fills the gaps of human bewilderment, adapting to the deepest traumas and mystical delights of the era. Myth is the Story humanity is telling itself to make sense of it all.

Separation Begins

By the time of the early civilizations, the Divine and Nature became distinct. Gods and Goddesses, more human, have wars and dramas, lavish feasts, and ritual ceremonies. These myths reflect the abundance and security of agricultural production and, notably non-nomadic, city dwelling. The myths helped early civilizationers explain the dumbfounding brutality and ecstasy of life: human drama, sexual temptation, organized war, and an unforgiving class system. Gods like Innana and Enki of Ancient Mesopotamia, the daughters and sons of celestial bodies, made elaborate journeys to the underworld, underwent trials of enslavement, and their deaths often coincided with natural phenomena like the Winter Solstice.

As the role of idolatry and worship increased in daily life, so did perceptions of human influence over the natural world. To pray is to influence a God, and at this point, Gods ruled nature. To that end, these myths were not seen as folklore or something ‘optional’ like contemporary organized religion. In early civilizations, myth and science were intertwined, myth and reason married in the everyday explanation of the sunrise, the harvest, the hunt, the famine, the plague and the drought. To an ancient Sumerian the underlying story was, “I live in a wonderful yet unforgiving world. I should appease the Gods in order to have a bountiful harvest and mitigate the risks of drought on my crops.” It was a practical spirituality.

Up to this point in myth history, the Divine, in some form, was still tied closely with Nature and its unpredictable forces. But as we enter the Era of Empires, monotheism takes hold and the relationship between the Divine and Nature grows even further apart.

Rise of the Human

Commerce, trade, and mercantilism matured to a point where people grew disconnected from their primordial connection to Nature – their food. In empires like the Byzantine and Roman, daily life for the common city-dweller was functionally removed from agrarian woes. People were losing the need for the Gods of the harvest, and the Pantheon would soon collapse. While monotheistic high holidays would roughly follow the pagan calendar, the stories of Abraham and Christ would serve a new regime of myth.

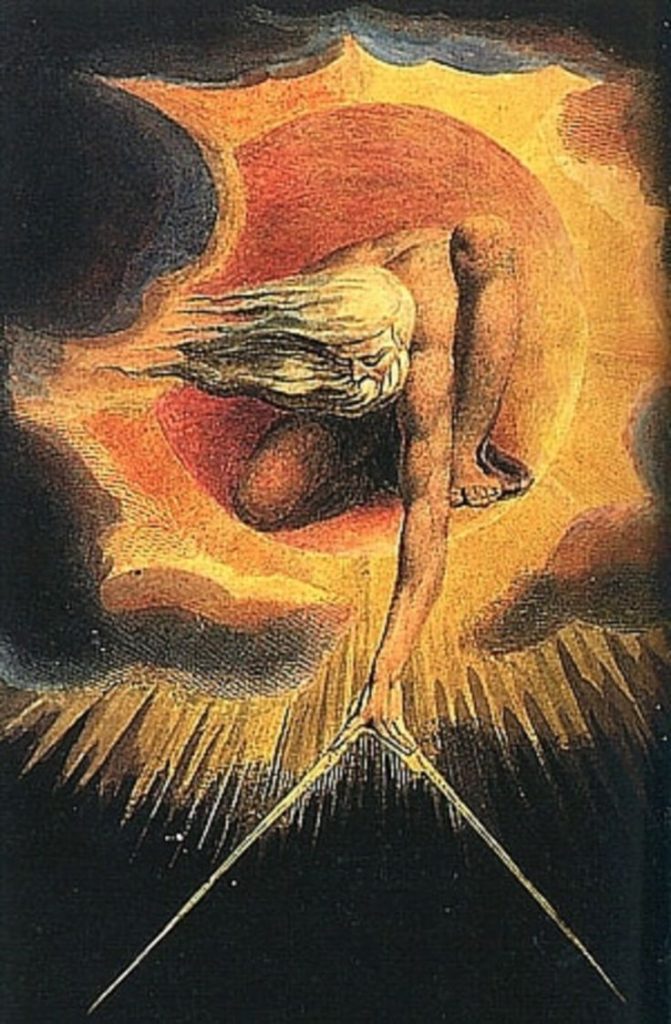

In the Era of Empires, humans begins to see God as the all-knowing creator of Nature, a top-down magician, a man with a plan, as opposed to the gods of early civilizations – Titans, who emerged from the primordial soup of the universe wielding brutal power.

And with Jesus, who was both the Son of God and a man, people, especially men, were reflected more clearly than ever before as all-creators themselves. One could say the ego of the collective was growing its control over Nature and forming a mythology of the righteous individual.

In parallel, the dance between myth and science becomes obvious in classical studies like astronomy. Until the 16th century AD, humankind widely accepted that the Earth was at the center of the universe. This supports virtually every post-Neolithic myth tradition, reinforcing the uniqueness and privilege of the human race at the center of the cosmos. This ‘geocentric’ model of the universe described how the sun and planets rotate around the Earth, had spiraling orbits to explain retrograde movement of planets, and all manner of assertions that are laughable by today’s scientific standards. But for millennia of recorded history, the myth of a human-centric solar system was backed by science.

Institutional sciences were, to some extent, conducted in the service of proving God’s greatness. The likes of Socrates and Galileo were prosecuted for their discoveries that didn’t align with the worldview, the mythology of that time.

The Gods of Cause and Effect

But a major shift occurs in the character of myth during the early Enlightenment. In his Essay on Human Understanding, John Locke espouses that the human mind is born a blank slate and shaped by environment and experiential factors, not pre-determined by God. Sir Issac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principa Mathematica boiled down the forces of nature into three simple principles.

The likes of Newton and Locke concretized the principles of Cause and Effect in the human psyche, they shifted the Story of Humanity forever. Cloaked in the rationality of science, a new era was born where God was not to be thanked for bounty, but rather, the laws of physics and philosophy could explain all Earthly matters.

With Newton’s spark, the Age of Reason, the Enlightenment, and the Renaissance slowly pulled the mysterious power of the Divine away from collective consciousness as the certainty of science filled the void. The certainty of science and the control it implies, became more palatable to the human psyche than the wild whims of a distant God. Ever so subtly, humanity began to worship the Gods of Cause and Effect.

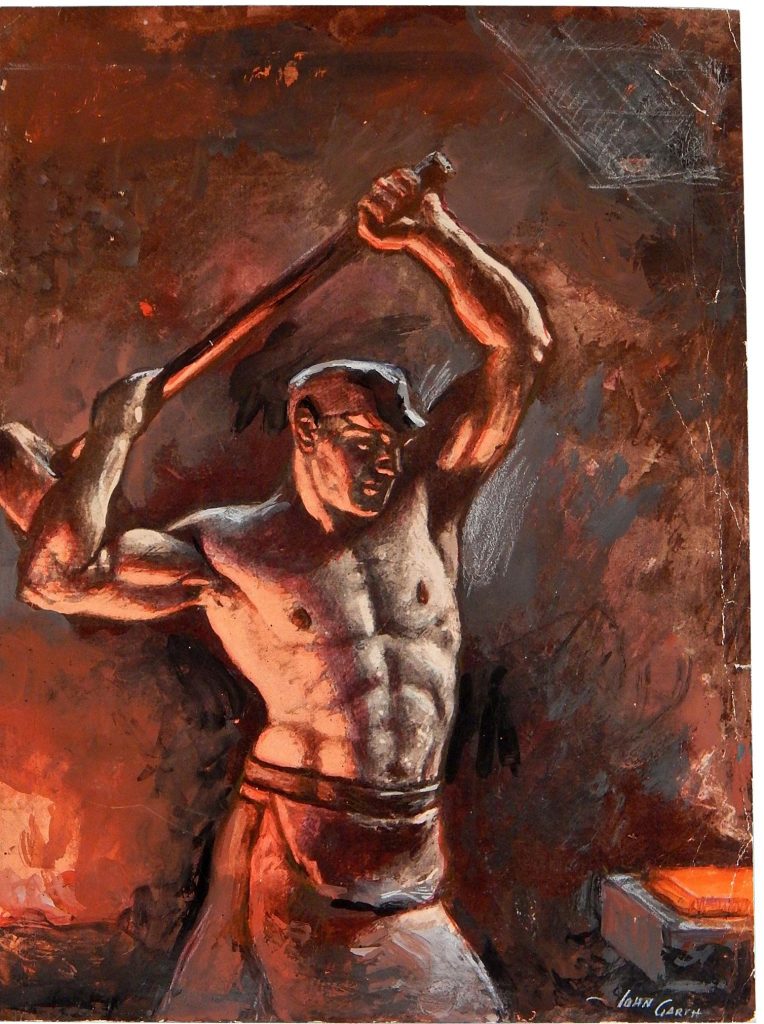

With the new mythology of science, our belief in the Gods of Cause and Effect would ignite widespread revolutionary thinking. Free to affect the state of Earthly matters, entire populations would topple monarchies in the French and American Revolutions. Free to tame the forces of nature, seeds of the Industrial Revolution were sown.

Mankind stepped fully into its power with this revolution, and the Divine saw its steep relegation to unearthly concerns. Nature, now even further from the Divine, was controllable and predictable. Transportation, entertainment, and even agriculture were gaining independence from the cycles of Mother Nature. In the same stroke, the collective psyche became fearless and disconnected from Nature too.

The beliefs in collective action and righteous individualism would dance through the setlist of the 18th through the 21st century. Erupting in spikes of concern and chaos around economic inequality or civil rights, the Industrial and Technology Revolutions have become the contemporary dance floor for myth. A mass eruption in automobile and home ownership, consumer goods, and consumer electronics would further reinforce assertion of control over Nature and the disconnection of the Divine from everyday happenings. Barring the Naturalist movements of the era, the mythical roles of the Divine and Nature would remain more or less unchanged. That is…until environmental disasters gained popular attention.

Seeking Balance

Clair Patterson was the geochemist who uncovered the mystery of widespread lead poisoning in America in the 1950s. Much like the beginning of the climate change debate, there was a collective denial of the problem. For people who wielded science for progress, it was too much to believe that individual actions, like driving a car with leaded gas, could cause population-wide poisoning and transoceanic destruction.

Enter Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson, telling of the adverse effects of indiscriminate pesticide use. Enter Jane Goodall, with her humanization of our non-human neighbors. Enter the Exxon-Valdez oil spill. Enter the Amazon Rainforest ablaze. Enter Greta.

Humanity’s archetypal detachment from Nature is now being challenged within a single generation. Our ability to operate independent of consequence is being denied. The pendulum is swinging back towards collective action, towards the sacrifice of the righteous individual for the benefit of the collective. Humans are becoming once again humbled in the face of Nature, like so many millennia ago.

And with this Great Turning, the collective psyche is abuzz, frantic, and clouded. “Can we do anything right?” There is a scramble for answers and solutions, the majority of which still rely on the old myths and a spiral into political polarization, wars over resources, vengeful advocacy, or outright denial.

These are the growing pains of a new myth emerging. Social unrest, mental disorder. This generation faces greater uncertainty and polarization than any of our living ancestors.

In The Upswing, Putnam and Garrett map America’s “social cohesion” between the 19th and the 21st century. Low social cohesion means political polarization and worldview disagreement among the general population. Analyzing extensive data sets, they find the two lowest points in America’s history of social cohesion: first the Gilded Age, and the second, today. Only in the grim times of an industrial smokestack chugging, child laboring, economically cleaved America, was political divisiveness as bad as it is today.

However, The Upswing shows that in the intervening years, from the early 1900’s through the 1960’s, America experienced an extraordinary reduction in economic disparity. Social cohesion increased in parallel. The Collective responded to the poor working conditions and inordinate wealth accumulation of the time.

Today, we live with a dominant myth of Righteous Individualism, signified by wealth fetishization, populist rhetoric, and technology addiction. A hobbled, yet mighty narrative of Collective Action is only beginning to rise again. While a painful experience, the growing prominence of Nature in our mythology is causing the pendulum to swing once again.

So, what is the myth of tomorrow, the one that helps curb climate change?

From the mid-60’s, there has been a popular resurgence of indigenous cultural wisdom, from how to tend the land, to honoring Mother Earth in ritual ceremony. These resemble the first principles of myth, back in the Paleolithic age, where our everyday existence is steeped in reverence for our reciprocity with Nature. Could it be that the next era is one of individuals choosing to live different lifestyles?

Could it be that a deep-shift in our mindset would compel us collectively scale-back our consumption? Travel less? Eat only local? For those privileged enough, to give up all things that are out of balance?

Or are we too locked-in to global supply chains to transform? Are our lifestyles so cushy, that we’ve inadvertently limited our ability to scale back? Does survival ultimately mean polluting Nature and ourselves?

“Climate grief” is an emerging phenomenon that provides a window into the direction of myth. In a 2019 poll by the American Psychological Association, 68% of US adults reported ‘at least a little’ anxiety about climate change. Almost half of young respondents (ages 18-34), said their anxiety about climate change was affecting their daily lives. It’s clear to most Americans that our daily lives are not sustainable, and it’s tearing us apart from the inside out. Could it be that we, collectively, feel trapped into making unsustainable lifestyle decisions?

The next mythology must bridge this paradox: an economy locked-in to unsustainability, juxtaposed with a pervasive, rising reverence for Nature. Ideally, the macro forces that cause climate change – exploitative economics, consumerism, and technology fetishism – will begin to shift as our mythology changes. Maybe we will learn to revere those things again that regenerate ourselves, Nature, and our collective psyche.