A Participant Critique of the French Mutual Aid Network, Solaris

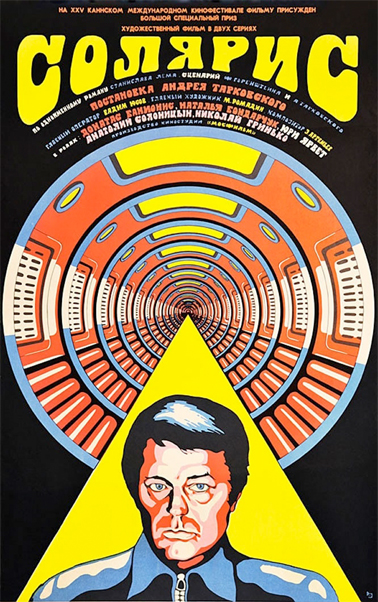

A few months ago, someone shared with me a link to a video in French that immediately caught my attention. It introduced a new network, called “Solaris.” At first I wondered whether it might be an Andrei Tarkovski fan-club. I had always found the Soviet director’s famously long, slow, and deeply poetic works, such as Mirror (1975), Stalker (1979), or Solaris (1972), rather fascinating. The latter is about a cosmonaut who travels into distant space where, in orbit around a mysterious planet, he finds the borders between dream, memory, and reality are beginning to collapse.

But the network has little to do with Soviet cinema – and everything to do with another kind of collapse. This Solaris is dedicated to the creation of a multitude of self-organised, hyper-local groups, all around the world, in order to foster solidarity and mutual aid between neighbours. The rationale for doing so is that authoritarian governments are on the rise, as exemplified by stringent and divisive Covid policies; and that, simultaneously, energy, communications and food supply disruptions are to be expected in countries like France shortly, partly as a consequence of the war in Ukraine, described as about to spread to the whole of Europe. It is therefore necessary for ordinary citizens everywhere to organise, urgently, in order to prepare for “severe disruptions” to normal life.

The method for doing so is supposed to be as decentralised as possible. Anyone is invited to form a team of three local coordinators, who spread the word and invite their neighbours to meet one another and form a mutual help group. The coordinators’ role centres around collecting from every group member a list of useful equipment and competences that every person is willing to put in the service of the group, on a voluntary basis, to collectively face the oncoming catastrophes – from chainsaws to first aid skills. Each group is also invited to organise workshops and share knowledge on how to prepare an emergency ‘BoB’ (Bug-out Bag), forage for wild edible plants, or filter water. There are supposed to be no chains of command: every group can choose to replace their coordinators if they aren’t satisfied with them, and no-one from any other group (be it at regional or national coordination levels) can tell a given group what to do.

I was enticed by this method of organising. Although the focus of Solaris seems clearly practical rather than political, the general spirit reminded me of anarchist self-organised affinity groups, and even of the municipalist (or democratic confederalist) ideas put forth by the anarcho-ecologist thinker, Murray Bookchin. I knew these radical ideas had been implemented to a degree by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (also known as Rojava), after the start of the Syrian war in 2012.

But I also felt cautious, as I saw no set of guidelines (nor signs of capacity-building) around how to manage issues of power within a given group, besides a milquetoast – and rather unrealistic – recommendation for coordinators to “leave their ego in the dressing room.” For example, how to prevent coordinators from using the personal information they had, about each member, for their private purposes? And how to hold them accountable?

Another reason for caution was that I quickly became aware Solaris had emerged from the French ‘anti-vaxx’ movement. Not that I considered myself ‘pro-vaxx’: by that time, I had developed many strong feelings about the way governments – and particularly the French government – had been managing the pandemic. I still consider these policies to have been largely misguided, harmful, and favouring increased state surveillance (not to mention disaster capitalism). But as someone whose opinion shifted gradually, I had always tried to listen and empathise with ‘those in the other camp’, and felt wary of associating with what I felt might be a slightly militant network.

However, I decided to follow my curiosity.

First Contacts

To my surprise, I found that in the space of a few months since its creation, Solaris groups had spread all across France (and to other countries, largely francophone) – including to my neck of the woods. So I decided to get in touch. It was easy, as every group can create its own open communication space on the social network Telegram, which people can join freely. I was soon able to attend a meeting, which took place simultaneously online and offline. Nearly 20 people attended, which seemed like an impressive turn-out for a small town like mine. They were mostly middle-aged or retired folks, with average education levels and little to no activist backgrounds: a hospital nurse, a kindergarten teacher, company employees. I might have brushed shoulders with some of them on the bus, or while grocery shopping. Ordinary people freaked out about the future.

As expected, the meeting felt a bit chaotic, as facilitation was improvised and people were still getting to know each other and figuring out what to do next. The three coordinators were quiet and didn’t seem confident in their role yet. People excitedly discussed various other Solaris groups that existed in the region, and who was doing what – “So-and-so are prepared to host 17 people at their home if need be: they have foldable cots, and enough drinking water for two weeks!” We compared the respective merits of different forms of emergency supplies, from army combat rations to freeze-dried foodstuffs. Another recurrent theme was that of operational security, which I found intriguing: “Send all your email through Protonmail!” or “Download Telegram directly from the official website, to make sure the code hasn’t been tampered with.” I don’t often hear older, non-techy folks talk about such things. The subtext was obvious. “It is a fact that the DGSE (French secret services) are keeping an eye on us,” declared a retired fireman, who said he had contacts in the army.

The discussion also touched upon the origins of the network. Solaris started off in October 2021 in an unlikely location, a town in the rural département of Aude, not far from where I live. The founder was one Frédéric Vidal, a former journalist who nobody seemed to know much about. Vidal appeared in some of the videos I had watched. Fifty-something, with high cheekbones and long hair somewhat reminiscent of an Argentinian gaucho, he had come across to me as stolid, humble, and humane. He was rumoured to have helped organise several active Solaris groups where he lived.

The meeting dragged on, and coordinating conversations in-person and online with a single cell phone proved to be a challenge. I left early. I was disheartened by the lack of leadership or facilitation, but still curious to see whether this might be a good way to start getting more involved in community-building activities locally. Later, I heard a decision had been made: a workshop would soon take place to teach people how to use CB radios to communicate with one another. The use of such equipment is strongly advocated within Solaris, as a means to maintain communications between group members – and from one group to the next – in case of a breakdown of internet and cellphone networks. As I wasn’t keen to invest in those geegaws right away, I didn’t join in.

A few weeks later, however, I attended another workshop, which took place in person at someone’s home. It was about water filtration and storage. Though instructive, I didn’t sense I was learning anything more than what I could have found on YouTube. Moreover, I felt uncomfortable with the way conversations were monopolised by a few individuals – including the rather assertive retired fireman from the previous meeting, who was holding the workshop. He had laid out a complete list of other instructional activities that would be taking place in the future. At the bottom of the page was a strange motto he had crafted: “Whoever neglects to prepare themselves should prepare to be neglected.” Just a detail, but it irritated me. What it implied was that only active ‘preppers’ deserved to be saved from whatever was in the offing. Where was the “solidarity” that Solaris was supposedly about?

I started to feel less inclined – and too busy – to participate in group activities. Nonetheless, I stayed in the Telegram group and scanned conversations now and then.

The Great Call

From early on, I was encouraged by the emergence and rapid expansion of Solaris’s fractal model of local organising, reliant on the use of Telegram and a few simple steps for bringing people together and building up local self-sufficiency in a time of generalised dependence on long and fragile supply chains. I also appreciated the general message I perceived from Solaris videos and webpages, which focused on solidarity, mutual aid, discarding transactional exchange, fostering “the love of everything alive” (source), as well as enabling relationality and belonging in Western societies that are afflicted by an epidemic of loneliness… “without a hierarchy, and without a leader” (source).

On the website, some language did feel strange, for example, “[Solaris] mettra en lien les hommes et renforcera ce lien” (source), which can be translated as “Solaris will connect men together, and reinforce this link” (“les hommes” has long stood for “humanity” in French, but tends to be less widely used in this sense, nowadays, for obvious reasons); or “L’Esprit SOLARIS… C’est marcher droit, ensemble, le regard clair, la main ferme, le souffle calme, tournés vers un présent constructif et positif” (source) (“the Solaris spirit is about walking straight ahead, together, with clear eyes, a firm hand, a calm breath, facing a constructive and positive present”). Whose “firm hand” is this, I wondered, and what is it up to? But I chalked it up to romantic, old-school writers.

However, my discomfort grew a few months later upon reading an announcement from founder F. Vidal, which was forwarded to my local group’s Telegram space. I later realised Vidal’s messages were regularly forwarded and pinned to the group page by my group admin, a privilege from which no-one else seemed to benefit. It was around mid-June. Vidal said that a “Great Call” (Grand Appel) was hereby being broadcast across various networks, including Solaris, which were uniting to create a new movement: Freedom March (La Marche pour la Liberté).

The purpose of this movement was explicitly about generating more solidarity and mutual aid, and “to prioritise the protection of the most vulnerable people, starting with children going back to school after the summer” – in reference to fears over compulsory vaccination programs for children, which so far have proved unfounded in France. Vidal acknowledged he had proactively started this initiative, without consulting the network at large (because “the operation had to remain as discreet as possible and to be launched very rapidly,” for unstated reasons), and said he was therefore open to criticism. But he also wrote that he “[did] not doubt that the immense majority of Solaris members would agree with this call,” and stressed that every cell was free to decide whether to actively engage with other fellow networks. Concretely, this meant local group coordinators could choose to add members of other networks to their directory.

The Telegram message shipped with a link to a video, shared – like most other Solaris content – on the independent viewing platform Odysee.

The video is titled “The Great Call” – although its original full title, as displayed on this blog post showing the full transcript, is rather “The Great Call to the Sovereign People of France.” It opens by denouncing how “world events that have unfolded since 2020” have brought about “the execution of worldwide policies, decided by a few.” Relying on “fear… and enormous lies,” and enabled by “true media terrorism,” these policies “aim at imposing a totalitarian way of life, through corrupt organisations financed by the richest people on the planet.” A “false sanitary pretext” is being used, “just like ecological pretexts… to better cow populations.”

Unmistakably, although the terms “virus” or “Covid” are never uttered, the Great Call is about rising up against Covid-19 policies and the “New World Order.” It urges the viewer to join networks opposing this state of affairs, so as to “create real solidarity locally and provide quick and efficient responses to any expressed need.” It also mentions how even “the State bodies… which still harbour healthy values” will have to “choose their camp.”

Following the recorded speech segments, the video presents photos of demonstrations against Covid-19 policies taking place in various countries, superimposed with slogans in English and French, and claiming that “For the first time, a large European movement is mobilising.” It concludes with a list of networks people are invited to join, displayed on a background of paintings by Thomas Cole – including from the famous series The Course of Empire, which depicts the rise, decay, and collapse of European civilisation, followed by its return to an idyllic, pastoral state.

The Dark Side of Solaris

The video left me with an unpleasant taste in my mouth. What was it that felt so unsettling?

It wasn’t the call to resist Covid policies. As I mentioned, I had no love for most of the measures decided by the French state. Rather, I was bothered by the aesthetics and the language. The music, especially, grated on my nerves. Towards the end it spirals out of control, into an orgy of strings and choirs reminiscent of Hollywoodian peplum extravaganzas (Gladiator, anyone?). As for the language, it carries the same heavy whiff of old-school heroic and romantic spirit that I detected in other Solaris messaging, but on steroids. The video tells a story of a struggle between forces of light (the people) and darkness (government) in bombastic and deterministic terms, with phrases like “We are all at a crossroads… Conciliating the fear of saying ‘no’ and freedom of choice is no longer possible.” But I was particularly put off by references to “the peoples of the West” or the “will” of the “sovereign” people of France, whose “veins” flow with an “innate or acquired inheritance.” As someone who mostly identifies with anarchism and the radical left, I was deeply concerned about these phrases, which sounded right-wing and nationalistic.

This prompted me to check what people were saying about the video in my local Solaris Telegram group chat. No-one voiced any comments about it, although the admin and someone else posted enthusiastic emojis. As I scrolled up the group timeline, I reached the time of the results of the recent French presidential elections. These elections saw centrist Emmanuel Macron re-elected on a platform that shamelessly copy-pasted many themes from the discourse and programme of his extreme-right adversary, Marine Le Pen, who came in second, with her highest score ever. In the following legislative elections, her party, Rassemblement National, grew tenfold at the French National Assembly, and its members conquered important new positions in the state apparatus.

In our Telegram chat, several members of our group expressed disappointment that Le Pen had not won the election, and one even commented that “Marine would have made a better shepherd for the French population.” My heart sank when I saw that no one challenged this comment, and that it was cheered by several group members.

Of course, this is just an anecdote, and does not mean that Solaris is mostly won over to the extreme-right. However, a few weeks later, an article presenting three writers’ investigation of Solaris threw even more cold water on whatever remained of my interest in this network. The text was published on the anarchist website LundiMatin. It has the clickbait title: “Solaris Network: Fake Dissidents, True Ecofascists.”

Initially, some of what it says made me feel like dismissing the whole piece out of hand. In particular, it confusedly lumps the use of “horizontal” governance processes like Holacracy together with ideas of collapsologists like Pablo Servigne – and those of notorious representatives from the French alt-right movement and other conspiracy theorists. The authors claim that anyone speaking of collapse while arguing in favour of decentralised governance systems are in fact “ecofascists,” who instead of calling for political action to reduce the impacts of current harmful social and ecological disasters (as a result of capitalism and consumerism, for example), are in fact trying to convince people to simply “live with these disasters, while awaiting the manifestation of a supreme leader who will guide us through this ordeal, including through incitements to hatred and preparing for war.”

There is a lot to unpack in this accusation. Suffice to say that, indeed, ecofascist trends (i.e. perspectives that combine environmentalism with fascist viewpoints and tactics) are emerging around the world – as has been most tragically exemplified in terrorist acts such as the mass shootings that took place in Christchurch, El Paso, and Buffalo. In France, too, seeds of recognisable ecofascist thinking can be identified among proponents of the Nouvelle Droite neo-fascist movement, although their political influence remains marginal at present, including within Le Pen’s Rassemblement National party. However, associating collapsologists with this trend, such as Pablo Servigne – who has professed his leftist politics and anarchist leanings on several occasions – or supporters of decentralised governance models, is sheer nonsense.

Besides, it has also been shown repeatedly (for example, here, here, or here) that envisioning the collapse of industrial consumer societies does not mean giving up on political action, nor does it necessarily have anything to do with waiting for a providential saviour to emerge and set things right. The Deep Adaptation Forum itself is a living statement to the contrary. A network founded on the premise that societal collapse is either likely, inevitable, or already happening, the Forum explicitly condemns in its Charter “all authoritarian, fascist, or racist discourses and responses.”

Ecofascists?

Nonetheless, I found that other parts of the article were much more worthy of consideration. For instance, the authors asserted that Solaris founder F. Vidal is the author, under the pen-name Le Passeur (which means “The Smuggler” or “The Boatman”), of the long-running blog Urantia Gaïa. According to a shady-looking web directory, Vidal does appear to be the owner. What confirms this possibility in my view – beyond the unmistakable writing style – is that Urantia Gaïa published several articles centred on Solaris, such as this one, or this one, featuring the “Great Call to the Sovereign People of France” video and its transcript.

The blog was online for over 11 years. Le Passeur announced that he would close it down in August 2022, without explaining why, even though Urantia Gaïa had gradually attracted a substantial readership. He was true to his word. Could this be due to some potentially embarrassing content that he was hoping to bury? For example, witness this post, according to which “the term SARS-CoV-2, in Sumerian phonetics, means Harvest or Genocide depending on how it is broken down”; several other texts, such as this one, supporting Donald Trump’s narrative of an election that was stolen due to the plot hatched by an evil cabal; or, more worryingly still, the following prophecy:

“The sword of France will rise in the hand of a man of Providence, transparent, not driven by his ego, and carried by the spiritual energy that suits what the nation needs. A man capable of federating, without aspiring to cling to power, the Gallic tribes…. This man, I believe, has already manifested himself, emerging from a luminous breakthrough far beyond human questions….” (Dec. 2020)

This providential, ego-less, and transparent Gallic superman who will lead a “crusade against the corrupt institutions” of his country, with the support of the “sovereign people” and, “undoubtedly,” of the army… Who could this be?

Whoever he is, this übermensch can count on many allies. Thanks to the Lundi/Matin article, I found out more about the speakers who appeared with Vidal in the Great Call video, all spokespersons for the networks mentioned at the end. Some, such as Christine Deviers-Joncour, are fond of quoting from QAnon conspiracy websites; others, such as Jacob Cohen or Marion Sigaut, are known as close followers of Alain Soral, one of the most influential extreme-right ideologues in recent French history. Étienne Chouard is notorious for doubting the historical existence of Nazi gas chambers, and Chloé Frammery has made it her mission to question the reality of climate change.

In other words, Vidal did choose to make the Great Call video together with prominent representatives from the French “fachosphère.” Though far from being known for their environmental concerns – which makes it far-fetched to label them “ecofascists” – the politics of these web celebrities all tend to the hard-right side of the spectrum. No wonder I couldn’t stomach their language, or their musical tastes!

Where to Find Community?

These discoveries left me feeling angry and disgusted. By all accounts, the far-right has never been so strong in France since the end of World War Two. Marine Le Pen could very well become the next French president, the implications of which are enough to send shivers running down my spine. On the other side of the Alps, Georgia Meloni, who has praised Mussolini and been involved in several neo-fascist parties, is another example of such trends – she has just stepped up as Italy’s new Prime Minister.

I have stopped attending the occasional gatherings within my local Solaris group, which seem to have become sporadic anyway. How could I ever want to maintain relationships with others in a network whose very philosophical foundations are a reflection of the rise of fascism in France, and elsewhere? A network founded by someone believing in the arrival of a national superhero, sent by cosmic forces to selflessly purge the corrupt institutions of his country – perhaps with a little help from the army as one of these institutions that “still harbour healthy values”? I can’t help but recall the key role that military and paramilitary organisations have played, historically, in the ascent to power of several fascist regimes, such as that of General Franco in Spain.

Wondering how much the other group members knew about all this, I shared a link to the Lundi/Matin article in our local Telegram chat, asking folks whether Vidal or anyone else had responded to it publicly. Reactions were subdued, to say the least. Mostly, my message was ignored. Only a few days later did someone reply, curtly, regretting that the article was written by “anti-resistants” who made “baseless claims.” Shortly afterwards, the group admin posted a link to an article that made a case for the flat earth theory. Despair rose in me.

And yet – I could not help reminding myself that the people I had met in these gatherings seemed, in many ways, much like me. Worried about the increasing weirdness, unfairness, and scariness of the world. Fearing the collapse of everything they held dear. Looking for others with whom to find a sense of belonging and safety in this atomised society. Seeking a community in which to feel taken care of, and in which to take care of others. How many of them voted for Marine Le Pen? How many did so out of a sense of fear and disconnection? Or disorientation, as a result of fragmented worldviews? Hannah Arendt famously identified loneliness – and the lack of a common ground of experience with others – as enabling the rise of totalitarianism:

“The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction, in other words, the reality of experience, and the distinction between true and false … people for whom those distinctions no longer exist.” (The Origins of Totalitarianism, 1973)

Spoiler alert! At the end of Tarkovski’s Solaris, the main character appears to return to Earth from the space station where he was sent, and reunites with his father. But it’s an illusion: in fact, he is trapped at the surface of the mystifying liquid planet he has been orbiting around.

I wonder: How may I find, or help establish, more authentic common ground with those around me who have been led to support toxic ideologies? How may we come back “down to Earth” (in the words of Bruno Latour), together, without creating further separation and harm, or trapping ourselves in hermetic bubbles of alternative reality? How to strive for deep political change in an increasingly violent context, while foregrounding values such as compassion, openness, and solidarity? How to heal our relationships to ourselves, each other, and the rest of the living world, in this time of momentous and confusing change?

As I mull over these thorny questions, Rainer Maria Rilke’s famous words come back to me:

“Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.”

I intend to keep looking for others with whom to better live my way into new answers. But sadly, I doubt I will find many in Solaris.