The Eco-Institute at Pickards Mountain | My Experience as a Black Participant-Turned-Leader

Note: The Eco-Institute at Pickards Mountain is an Earth sanctuary and learning community dedicated to healing the human-Earth relationship. The educational farm resides on 28 acres in the Piedmont of North Carolina, eight miles west of Chapel Hill.

As I do believe in a higher power, it feels like divine intervention that my path has converged with the Eco-Institute’s —a hidden gem just 20 minutes from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where I received my undergraduate degree in May of 2020. While I was in college, I had no knowledge this space even existed before my friend Abbey participated in the Eco-Institute’s Rising Earth Immersion in 2019. It’s funny now to remember my thoughts about it at the time, including my absolute non-interest in convening with nature or being part of a farm community. I was happy for Abbey and the positive impact she had from the program, but thought, that’s not for me.

Nevertheless, as my college graduation approached, I found myself wondering how in the world I could pursue my future plans in the middle of an unprecedented global pandemic. Even more urgently, I wondered how I would sustain myself financially after losing my part-time job due to the pandemic, while also sustaining myself physically and mentally during this extremely stressful time. Five years of a hectic undergraduate schedule, including participating in the year-round consuming sport of Cheerleading for the school’s varsity teams, while regularly speaking out against systemic racism and police brutality as a campus activist and community educator, had already left me feeling worn down. This, in addition to spending the first half of 2020 trying to graduate during a pandemic, constantly grieving the murders of black people—my people—by an uncaring and unjust system, witnessing COVID cases and deaths climb each day—mounting the fears for the health and safety of myself and family—while also mourning the diseases’ disproportionate and deadly effects among black people, minorities and poor people, brought “burn-out” to a whole other level. I was nearly undone and in desperate need of space to heal from the unrelenting traumas and struggles of 2020. As I narrowed my focus on existing job opportunities, I was presented with the opportunity to apply for the position of Core Facilitator for the Rising Earth Immersion.

Processing Hesitations

I hesitated to apply for two reasons:

-

I’m a city-girl with chronic anxiety, and the idea of living among a bunch of bugs and animals that I usually assume will kill me has never excited me.

-

I was sensitive to the lack of ethnic diversity in the organization, and I feared being tokenized, unsupported, and misunderstood as the only black person in leadership.

However, after carefully reading the job description, the Eco-Institute’s mission statement, and seeing the expressed dedication to more decolonized education, inclusivity, intentional redirection of privilege for the purpose of shaping radical change and repairing Earth/human connections, I was encouraged to seriously consider this opportunity. Once I convinced myself that I most likely would not be murdered by some unheard-of species, I reached out to the Program Director, Alison Sever, to express my interest. After our interview I was even more interested in the opportunity, and I imagined the possibilities of what I could bring to the space with my own experiences and background, as well as what access to such a secluded, quiet, beautiful piece of land could offer me as a safe refuge for healing.

To prepare me for a leadership role, the Program Director, Alison, offered me a full scholarship to join for one season as a participant, while shadowing the facilitators and preparing to lead future cohorts. Again, I was hesitant…

Because I did not want to live in a yome, which is basically this room/tent thing in the woods,

Because, as a lower-income college grad, the idea of not working for five weeks was a bit unnerving,

And, because during this time of racial uprising and civil unrest, I felt guilty for retreating away to this beautiful space—like I was abandoning my duties as an activist.

Yet, I couldn’t deny what a privilege it would be to attend a $6,000 program that I knew I couldn’t have even thought about attending had it been any more than a couple hundred bucks.

Then I realized that I owed it to myself, my people, and my ancestors to rest, and felt affirmed in remembering one of my favorite quotes by one of my favorite activists, Audre Lorde: Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation and that is an act of political warfare.

Once I had the conviction that rest as a black woman is a revolutionary act and therefore my rest WAS essential to the current strivings for freedom, I set my mind on going and getting as much from this program as I possibly could. This still did not make the idea of staying in a wooden tent-like structure with no A/C in the middle of the summer more appealing, but the lease on my Chapel Hill apartment ended a day after the program was to start, and it was either a yome or my parents’ house. I figured I’d rather have the change in scenery.

Affirmation and Direction

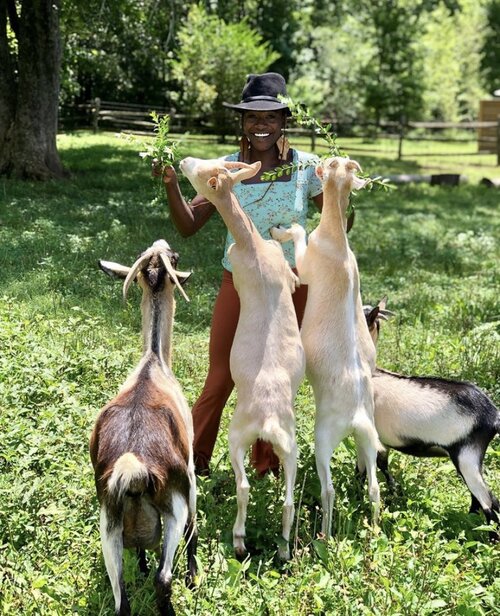

Attending this program as a participant was more life-changing than I could’ve imagined. Its uniquely holistic curriculum revealed many missing pieces in my activism. Like that I’d neglected to recognize the extent of which social and ecological justice are connected. As a black woman, I found the land connection to be one of my greatest sources of healing. Not only did I feel a sense of connection to my ancestors through the acknowledgement of their spirit and labor within the soil, but even just the act of paying attention to nature grounded me. Tending to nature became tending to myself, and through the guidance of educational resources introduced to me through the Eco-Institute, such as Emergent Strategy, by adrienne maree brown, I’ve been able to observe in nature how to best interact with change through her perfect example of “adaptability, interdependence, decentralized power, resilience and transformation.”

The program also introduced me to various BIPOC-led organizations doing collective work rooted in activism, alchemy, liberation, land accessibility and ancestral connection. One of the most impactful encounters for me was with the Lead to Life collective in Oakland, CA, and their co-creator brontë velez. I was deeply touched by Lead to Life’s practice of melting weapons used in acts of violence to create gardening tools, offered to the families and communities affected, and used to plant new life at the sites of that violence. After expressing my persistent pain and rage from the events of 2020, brontë highlighted the power in leaning into healing and radically transformational work, rather than constantly focusing so much attention and anger toward the systems we are trying to dismantle. This was another point of affirmation, liberation and redirection for me: that through creating, we can also dismantle.

I soon became involved with an associated farm nearby in Chapel Hill belonging to a Congolese-American couple who have now become both mentors and spiritual guides to me. Through divination, ceremony, ritual, and biodynamics, they are teaching me how to heal, lead, and transform through honoring the interdependence of all life, both seen and unseen, and observing the magic of this divine plan.

Interestingly enough, being around white people dedicated to allyship was a source of healing as well. It gave me a much needed glimmer of hope for the future of this country, and allowed me to examine how I wanted to show up as a historically marginalized minority in this program. I practiced taking up space, resting, being cared for and uplifted as a black woman, and maintaining my peace, while living in community with folks who are honest about the growth they have to do in the world of anti-racism. I carried all of this as I transitioned into being a facilitator the following season.

Co-leading a Rising Earth Cohort

My role as a facilitator of Rising Earth began in the Fall of 2020 with a 10-week immersion hosting 12 participants alongside my wonderfully supportive and insightful co-facilitator, Topher Stevens. Together we provided workshops around consent, community living, the impact of power structures and death culture, mindfulness, decolonization and imagination, self-care, and how to use one’s giftings for the common good. I facilitated healing spaces, specifically for people of color, which I felt were lacking during my time as a participant. All this while fostering better, more intentional allyship, and holding space for each individual of the group as a mentor and friend. These commitments create the foundation upon which we can confront challenges that arise within the cohorts. I know that some of the challenges we faced are common in other organizations and groups, so I will share them here. For example, the majority of the participants were white, young, and in the beginning phases of anti-racist work.

Our BIPOC participants, on the other hand, were heavily engaged with—and emotionally and physically drained from—years of anti-racist work, not to mention the reality of being BIPOC in a white supremacist society. To say the least, facilitation of this group was no easy feat! Instances of cultural appropriation, spiritual bypassing, indigenous erasure, poor accountability of privilege, and failure to be active anti-racist bystanders led to in-depth work addressing the harm and responsibility of white leadership, participants and the community alike. As a black woman who was also harmed by these experiences, to be able to show up fully for all members of the cohort and leadership team, it became even more crucial to create spaces for processing and healing for myself and other BIPOC participants, incorporating the practices of creating freedom from the inside out.

By the end of the program, I felt extremely fulfilled in seeing the growth of each participant as social and environmental justice warriors, change-makers, and more active anti-racist bystanders, but I was most proud in seeing the release and healing of BIPOC participants, made possible by the emphasis of rest, creation, unapologetic being and ancestral connection as necessary strategies to individual and collective liberation.

The fact that experiences like these are so largely unattainable to people of color because of our lack of generational wealth due to historical exploitation is devastating.

Even accessibility to nature in general is something that we don’t often have—in large part because of housing discrimination as well as our slim access to the very land our ancestors were forced to cultivate—pouring their blood, sweat, tears, and often their very lives into. I still struggle with feelings of anger and resentment around this reality because we deserve to heal and rest, and have spaces to be free to imagine and create a more liberated future. But I am grateful to be in the position I’m in now where I can help to bring that about for others as we continue to make this space accessible for all.

Future Building

I believe the impact that this program will have on the world through equipping young participants, of any racial identity, with holistic ways to reimagine and fight for their future is immeasurable. In revealing the destruction of land and Mother Earth to be largely linked to exploitative capitalism and colonialism, alumni of the program are now able to come from a holistic understanding to address climate change at its source. Through living in loving community with folks of various identities, while having real conversations about marginalized experiences and how we all experience white supremacy on a day-to-day basis—albeit differently—, Rising Earth alums from all backgrounds consistently develop more mindful, intentional, and radical allyship. In discussing self-care as an aspect of activism, alums are now able to recognize their needs on a somatic level and meet them in order to sustain themselves in this work. In linking community care to self-care, it is understood that since all life is connected, caring for others (human & non-human) is caring for oneself and vice-versa.

Lastly, when participants are facilitated in realizing their natural giftings when it comes to forms of service, they are better able to move in the world knowing how they can most efficiently and sincerely fight for the common good in their unique ways. It’s been amazing already seeing how graduates, equipped with new conversation skills, are having impacts in their own circles. From the white alums who are holding regular white caucus spaces to expand their capacities as more active allies, to the Black non-binary femmes who are finding better strategies for balancing rest and activism, to others leaning into creative film projects around Black expression and supporting food accessibility efforts—the updates I’ve gotten from the alums of this past fall cohort constantly have my heart beaming!

It is with utmost gratitude that I have been given the opportunity through this role to operate within my giftings as an activist, educator, creative, student, and healer in a way that has really confirmed my capacity to be a change-maker/change-shaper in this world. My hope is to continue doing this work while making spaces like this accessible to those who are most vulnerable and exploited in our society, and expressing the significance of being part of radically loving and spiritually-motivated community organizations like The Eco-Institute.

Photos | Courtesy Eco-Institute. except as noted