A Cosmic Twist

Look up into the clear night sky, and after a time you will perceive how the stars rotate around a central axis, as if on a great wheel. The ancients saw this rotation as the movement of a cosmic spindle, with its whorl in heaven and its shaft, the axis mundi, invisibly extending down to earth. Life and destiny were the threads spun by this spindle, the fabric of the world woven by the movement of sun and moon, stars and planets.

This image is remarkably universal. In The Republic, Plato beautifully describes the “spindle of necessity,” suspended from a rainbow-colored shaft of light, with an eightfold whorl of stars and planets, all singing in eternal harmonies, while the Kogi people of Colombia tell how the Mother Goddess set up a giant spindle to penetrate all nine layers of the just-created earth, still soft and unstable, which then solidified around it. The cosmic spider spins the world into existence in myths found all over North and South America, Africa, and Asia, and fate-spinning goddesses include the Germanic Norns, the Greek Moirae, and the Roman Parcae. In an apocryphal story, the Virgin Mary spins and weaves the veil of the Temple, which is the cosmos. 1

The primal activity of thread-spinning has become distant and unfamiliar to us today, through the mechanization of fabric production, but it is not difficult to recover a sense for it. Take a lock of sheep’s wool, which you can obtain from a craft store or fiber market, or perhaps even in its raw condition from a farmer. Carefully tease and puff out the short fibers until they form a fluffy ball. Starting at one point on the surface of this ball, pull out a small portion of the fibers, twisting them with your fingers. Keep pulling and twisting, gradually taking up more of the fibers, until you have a length of thread, or more likely a lumpy, unwieldy strand of thick-and-thin yarn—which may not be beautiful, but is nevertheless a transformation of the disorganized substance you started with.

You’ve just practiced one of the oldest of human handcrafts, dating back around 30,000 years, which, as we have seen, represented for our ancestors a human mirroring of the forces of the cosmos. When people became spinners, they were not merely serving a mundane need for clothing and shelter; they were establishing themselves as creators, bringing their own activity into play to shape the products of nature, no longer passive recipients or victims of natural events. Spinning brings a cosmic “twist” into the raw materials we encounter upon earth, giving them strength and continuity, and in so doing, the soul of the spinner is transformed, as well.

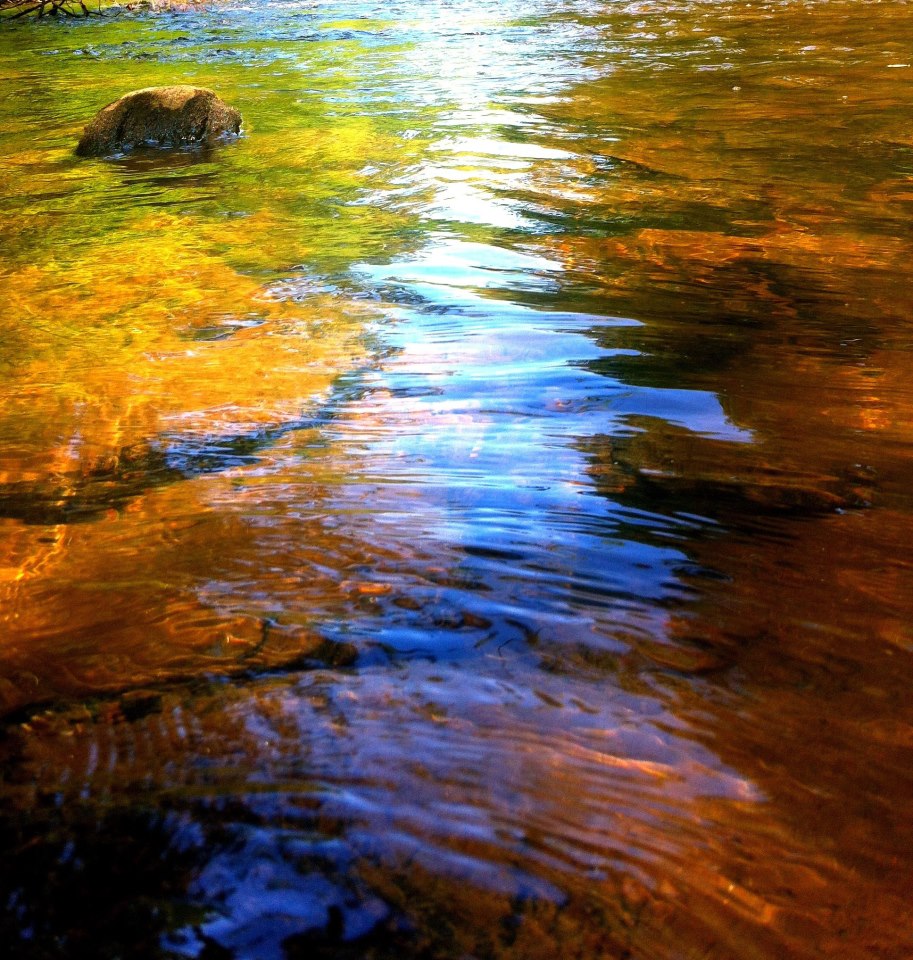

When we spin a thread, we are actually creating an extended, attenuated spiral, and the spiral is a cosmic form that repeats itself on all levels of our living world, from the shape of our galaxy to the helical structure of our DNA. More tangibly, spirals can be found everywhere in nature, in whirling clouds and swirling water, in unfurling fern fronds and seed-filled sunflower heads. Even the hair on the back of our own heads grows in a spiral pattern. The uneven, rotating crimp of sheep’s wool is actually what makes it much easier to spin than smooth fibers like cotton and flax; the wavy fiber complements the movement of the spindle, and locks the spiral structure in place.

When we spin a thread, we are actually creating an extended, attenuated spiral, and the spiral is a cosmic form that repeats itself on all levels of our living world, from the shape of our galaxy to the helical structure of our DNA. More tangibly, spirals can be found everywhere in nature, in whirling clouds and swirling water, in unfurling fern fronds and seed-filled sunflower heads. Even the hair on the back of our own heads grows in a spiral pattern. The uneven, rotating crimp of sheep’s wool is actually what makes it much easier to spin than smooth fibers like cotton and flax; the wavy fiber complements the movement of the spindle, and locks the spiral structure in place.

The spiral dances of the moving stars and planets were tracked by ancient astronomers, and humans very early took up this motif in their artworks and cultic images, chiseling spirals on passage tombs in Ireland and rocks in the Arizona desert, carving them on Chinese jade animals and the Ionic column capitals of Greece. The originators of the art of spinning must have felt that they were echoing the forming of matter by cosmic forces.

Tools were soon invented to make the process quicker and the products more consistent. Probably first a stick was thrust into the fibers, which could then be rolled down a thigh instead of doing all that tedious finger-twiddling. This is something you can also try out yourself, using a small, smooth stick with a hooked end that you pick up in the woods and trim to suit your needs. A more complicated development involved using a length of spun thread to tie a flattish, roundish stone together with a protruding stick, thus making a weight to drive the turning motion and a handle that could be used to start the stone spinning, as well as to wind the thread around as it was produced. 2 In time, this evolved into human-crafted spindle whorls and shafts, which give us Plato’s cosmic image, and the spindles of countless fairy tales.3

Spinners were imitating a divine process, and their work and their tools were always invested with symbolic meaning. The discovery of a spindle made of precious silver and gold in a Neolithic grave site in Anatolia, Turkey, demonstrates just how far back this symbolic, ritual significance extends. Meanwhile, the familiar stories of spindles and spinning that have come down to us often make clear that dangers and risks are involved in such an undertaking. If performed without reverence, it could lead to disaster.

In “Mother Holle,” for example, a story about two stepsisters, the industrious spinner reaps a golden reward, while the one who is too slothful to complete her task is punished with a hideous fate. This is more than a cautionary tale intended to frighten girls into fulfilling their societal roles, for as Jacob Grimm himself described in his Teutonic Mythology, Mother Holle is a manifestation of a Germanic nature-goddess, Hulda; it is said that snowflakes are the feathers shaken from her bed. When the girls fall into her world by tumbling into a well, they enter into the world behind nature, the world of the elemental forces that cause snow and rain, growth and fertility. Diligence in spinning is a sign that one is worthy of taking up that cosmic task, of becoming a co-creator with the divine. The alert awareness and feeling-sense required for good spinning are equated with compassion; the good sister answers an apple tree and an oven that call out to her for help, while the lazy one ignores them. Her failure dooms her to be covered with pitch, an outer sign of her inner insensibility.

Mechanization and materialization of the cosmic spinning activity can also lead to dire results, as shown in the tale of “Rumpelstiltskin.” In this story, the girl is a poor miller’s daughter, and the mill, like the spindle, is a wheel that resonates with the cosmic motion of the heavens. But rather than a simple tool for bringing order into chaos, it is a huge machine that crushes and pulverizes the living grain into a lifeless powder, rendering the miller poor indeed. To return life and value to this material, turning it into bread, would require a further step of transformation, of hard work and patience, but instead of humbly acknowledging this, the miller is moved by an impulse of worldly greed. He makes a wild claim that his daughter can spin straw into gold, and a grotesque trickster figure steps in to do it. Faced with her impossible task, unable to admit her inadequacy, the girl enters into a bargain with the subhuman creature.

When he claims her child as his reward, the girl, now a queen, has to earn back her life-giving power of transformation. And this time the way is through language, through naming. She must name the unknown and feared element in her life, must know it intimately, in order to overcome it.

It’s no accident that spinning is associated with language, that we speak of “spinning” a tale or telling a “yarn.” This, too, represents a step toward cosmic awareness, a human participation in the processes that create our destiny. When we look at events with such a higher awareness, we can perceive the links between them and come to a better understanding of their true essence. Spnning is rescued from falling into a mechanical search for material gain, and transformed into a quest for meaning and knowledge.

As anyone who has tried it knows, spinning is not a mindless task. It requires constant attention not to end up with a broken thread or a tangled mess. At the same time, the rhythmical balance of hand and mind working together is deeply satisfying and calming. The spinner may find her own thoughts changing, becoming organized along with the fiber, leading to new inspirations and insights. An inner “golden thread” can be sensed, one that connects us to the cosmic rhythms which created us.

This is the value we can give to our own lives, when we accept what we have been given, and shape it in wise accordance with cosmic laws, rather than attempting to deny or subvert them. In taking the latter course, we spin ourselves into another form of disaster. When in the story of “Briar Rose” or “Sleeping Beauty” the king hears a prediction that his daughter will prick her finger on a spindle and fall into a deathlike sleep, he attempts to avert that fate by burning all the spinning wheels in the kingdom. Ignorance cannot turn away a hard destiny, though; the princess’s curiosity leads her to touch the first spindle she sees, ironically bringing on the very doom the king tried to avoid.4

A better solution is to observe, learn from, and imitate the cosmic rhythms that we perceive, and to create useful products full of beauty and harmony, rather than lusting after wealth and power. In “Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle,” a king’s son is searching for a bride, who he declares must be at once the richest and the poorest. He comes to a village where he is directed to the richest girl, but moves on with hardly a glance for all her finery. The poorest girl, meanwhile, is sitting and spinning all alone in her little house; he likewise glances at her and rides away, but she looks after him until he disappears, and opens her window.

Remembering verses that her godmother used to say when she taught her the handcrafts that now form the basis for her livelihood, the girl sends out her spindle, shuttle, and needle as messengers to the prince, trailing marvelous fabrics behind them. He recognizes that his destined bride is this girl who is at once the richest and the poorest: poor in material wealth, but rich in skill and wisdom. They are married with great joy, and the tools of her labor are kept with honor in the treasury of the kingdom.

It is tempting for us to turn to external, mechanical solutions for our problems today, but human ingenuity and honest work never lose their value, when coupled with reverent appreciation for the rhythms of nature. If we can become loving creators, spinning the threads of life in harmony with the turning wheel of the cosmos, then the promise of all the ancient tales will be fulfilled, and their dangers averted.

NOTES

(1) For these and many other fascinating references to the lore of spinning and weaving, see Michael A. Rappenglick, “Cosmic Spinning and Weaving: Making the Texture of the World” in Archaeoastromy in Archaeology and Ethnography, edited by Emília Pásztor (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2007).

(2) In the short film “On Handwork” (viewable at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bfoByYLSBY8&t=43s&ab_channel=ChuckSmith), Renate Hiller demonstrates spinning with a stone tied to a stick, along with explaining its cosmic and human significance. I am indebted to Renate and her colleagues at the Fiber Craft Studio for teaching me much about both the practical and spiritual aspects of spinning.

(3) This tool, the handspindle, has been in use for over ten thousand years, and is still widely used today. The spinning wheel is only a few hundred years old. The many tales that feature spinning undoubtedly come from origins far earlier than their written incarnations, and would originally have referred to the older tool. This makes sense of a “Rumpelstiltskin” variant in which the girl is spinning on the roof (easy with the highly portable handspindle, not so much with a wheel).

(4) This tale may also have originally referred to a handspindle, or to an older type of hand-turned spinning wheel. Modern treadled spinning wheels seldom have sharp parts.

The four fairy tales referenced in this essay can all be found in the collection of the Brothers Grimm. Among other sources, the stories can be accessed on the site of D. L. Ashliman, https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/grimmtales.html: “Frau Holle” (#24), “Little Brier-Rose” (#50), “Rumpelstiltskin” (#55), “Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle (#188).