Seeing Truth in Van Gogh

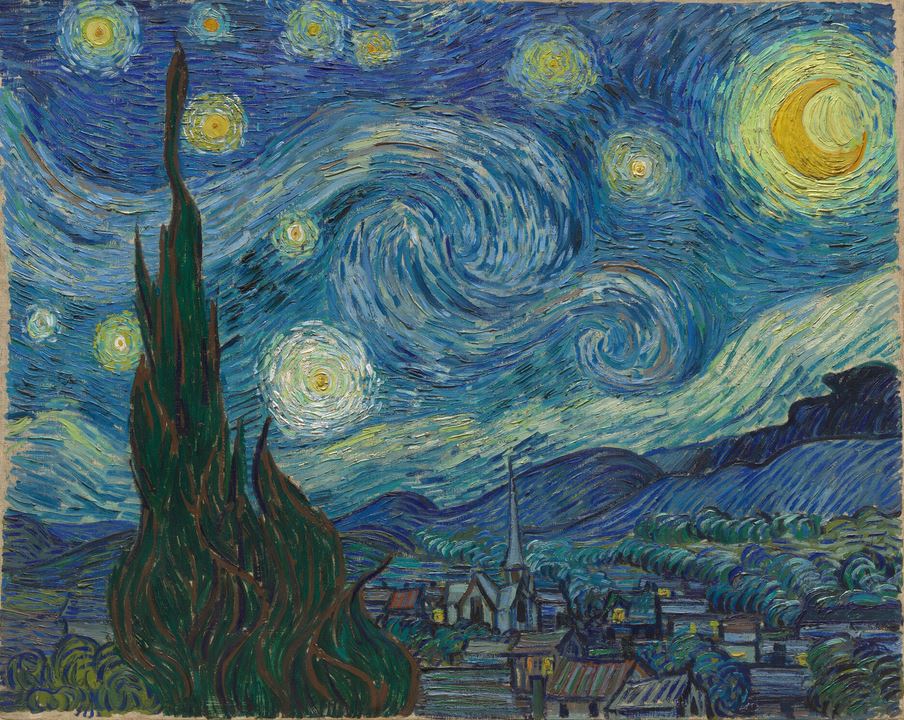

As a college student, I often stretched out on my bed and gazed up at the poster of The Starry Night I had pinned to the ceiling, wondering about the artist, Vincent van Gogh. Was he crazy? After all, he did cut off his ear. Was he stoned? Hallucinating? Just where did this wild swirl of starlight come from?

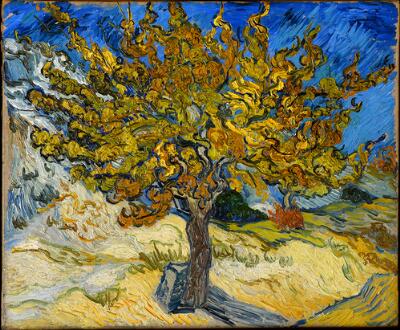

Decades later, I stand in a spacious gallery at The Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California, inches from another of his works, The Mulberry Tree, wondering why I love this painting so much, and why so many others do too. A trio of women hover behind me, waiting. But I don’t move. I look.

In a golden field, under a dramatic blue-toned sky, the mulberry dances, whipping its fall-gilded branches in an explosion of light and energy. With vigorous brushstrokes laid on so thickly they rise from the canvas, Van Gogh draws me into the scene. Branches shake. Leaves twist. Dry grass crunches underfoot. An unseen bird calls. At the base of the tree, touching the trunk, a mysterious object rests. A rock with an inscription? A tombstone? Had the mulberry tree been planted on a loved one’s grave? Was a life nourished by a death?

Following the lines of the trunk from the stone to the branches to the curled brushstrokes of the autumn leaves, I stop thinking and simply see. Then I get it, or to be more precise, it gets me. Van Gogh did not paint a mulberry tree, he painted the life force of the tree. He did not paint stars. He painted the turbulent energy of the cosmos.

***

Outside the window of the room where I write, I see part of a California live oak, framed as in a painting, its massive, forked boughs covered with grey bark like the skin of an elephant. From its branches hang leathery year-round leaves. Sometimes squirrels scramble over the tree’s boughs, teasing my dog from a safe perch high above the ground.

It’s mind-boggling that this formidable oak thrives on the narrow strip of land between a sidewalk and an asphalt road. But Van Gogh’s painting has opened me up to the tree’s essence—its power, strength, and energy. It’s no mulberry. It doesn’t sing and dance. It’s a mighty oak. It beats a drum and swaggers. When confronted, it stands firm. Sure, it may shake in the Santa Ana winds scattering leaves across the pavement, but its trunk is never broken and its thick branches hold fast. Van Gogh helped me see the inner truth of this oak, and I learn from its resilience.

***

In her book The Pursuit of Spiritual Wisdom: The Thought and Art of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, art historian Naomi Margois Maurer discusses the state of mystical consciousness in which an individual sees directly into the essence of reality, senses nature’s unity, and “feels himself to be part of the flow of universal life.” She goes on to describe it as a direct experience of fundamental truths which are inaccessible to our rational state of awareness and ordinary mental processes. It is a state of knowledge and feeling, a wakeful dreaming.

Van Gogh himself said it this way in a letter to his brother Theo, “I have a terrible lucidity at moments these days, when nature is so beautiful. I am not conscious of myself anymore, and the picture comes to me as in a dream.”

***

I was seventeen, sitting with my two best friends, on a hillside meadow edged by a forest. We were on a teenage girls’ adventure in the mountains of Virginia, far from school and family. The first day of spring had come upon us suddenly. Coats were peeled off. Patches of snow in the shady spots melted. We watched the earth turn green, and smelled the change of season in the rich seed-filled loam. Like the ghosts of winter, bare trees stood guard around us. No one spoke. Thoughts ceased. We lost ourselves in nature’s quiet beauty as in a dream.

***

To look at the stars always makes me dream. – Vincent van Gogh

I’m at home in a high desert canyon, lying flat-out on a vinyl pool chair, but there’s no pool here—just dirt, sagebrush, and countless stars in a dark night sky. I spot the blinking lights of a passenger jet headed north, and the dim but steady glow of an orbiting satellite. A meteor streaks across the Milky Way then vanishes. To the southwest, Saturn with its varied rings shines bright. Farther out, comets roam, stars explode, and galaxies die.

About 130 million years ago, two stars circled each other sending out whorls of hot gas. After both became neutron stars, they collided in an explosion so fierce it created gold. Light and gravitational waves from the explosion traveled across the cosmos, reaching earth where they were detected by instruments in space and around the world including LIGO, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory.

Van Gogh had no LIGO. He’d never heard of a gravitational wave. He could not have known of this cosmic event that created so much excitement among scientists on earth, yet he painted it—ripples in the fabric of space-time, the energy of creation, and the flash of destruction, the golden dance of the universe itself. It’s all captured in that wild swirl of starlight we call The Starry Night.

Above me, the Milky Way stretches across the sky. Maybe I’ll see the International Space Station, or if I’m lucky another meteor. The coyotes are howling now, my dog with them. I sit up and call her to me. She runs out from behind a clump of rabbitbrush and across the field, her white fur glowing in the starlight.

I zip up my jacket against the evening chill, then lie back on my vinyl pool chair and reflect on the poster that hung over my bed all those years ago. I imagine the artist whispering these words of advice. “Be clearly aware of the stars and infinity on high. Then life seems almost enchanted after all.”

***

In 1889, Van Gogh was residing at an asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, recovering from a breakdown, when he painted both The Starry Night and The Mulberry Tree. But he wasn’t crazy, and he wasn’t stoned. Surrounded by nature’s beauty, no longer conscious of himself, he gazed into the essence of reality, and painted what he saw.

Romantic philosophers believed the experience of mystical consciousness could be stimulated by works of art. I can vouch for that, for I enter a different realm when I stand before The Mulberry Tree. Feeling Van Gogh’s presence in his brushstrokes, I lose myself in the image on the canvas—the colors, the texture, the energy of the tree—just as I’d lost myself in a mountain meadow all those years ago. Van Gogh’s paintings are more than masterworks of post-impressionism, and this, I believe, is the reason so many love his work. His paintings are framed windows into the essence of reality, having the power to open eyes and hearts to the hidden truth that unites us all.

I appreciate your writing! This quote stands rock solid when you walk in places such as Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, or beside an iron imitation tree in Nome, Alaska. Thanks for writing, and teaching.

It’s a mighty oak. It beats a drum and swaggers. When confronted, it stands firm. Sure, it may shake in the Santa Ana winds scattering leaves across the pavement, but its trunk is never broken and its thick branches hold fast. Van Gogh helped me see the inner truth of this oak, and I learn from its resilience.

This article is a meditative experience. The inner beauty of Van Gogh’s paintings is expressed so beautifully. My heart is filled with joy at this explosion of reality itself.

Your words resonate deeply with me as you discuss the state of “mystical consciousness” and our unity with nature. You have expressed this idea beautifully and truthfully. Thank you.

great article into the next and subtle layer of reality. it is the dream world, the world beyond our physical senses. your writing acts as a bridge between these two worlds and clarifies what art is .

and i am led to wonder about the bridge between the subtle and the canvas itself…

I grew up with mulberry trees. They are ensouled in me. There is so much beauty in the world. Van Gogh is in the universe, as we are. I love the way you interweave this. Your piece has added to the depth of belonging we can feel in the world, together with Van Gogh.