Ritual Fire and Sacred Masculinity

Amos Kamil | My name is Amos Kamil. I’m a therapist and a writer. And it’s my pleasure to be speaking with Christopher Henrikson of Street Poets in Los Angeles and Boysen Hodgson of The ManKind Project. Can you say a little about that, Boysen?

Boysen Hodgson | The ManKind Project is a 37-year-old nonprofit organization that started in the US and is now in 12 independent regions around the world. We primarily do two things—we run intensive weekend trainings for men and we support peer-facilitated men’s groups. We have around 750 men’s groups operating in the United States, plus men’s groups in 26 countries around the world. In 2004, I did the New Warrior Training Adventure Weekend, got into a men’s group shortly after that, and I have been in a communications role with The ManKind Project USA for 10 years now. So, I’ve actively participated in a profoundly life-altering and affirming circle of men for 17 years.

Amos | Excellent. And, Christopher, tell us a bit about Street Poets.

Christopher Henrikson | Street Poets is a nonprofit organization here in Los Angeles that started in a juvenile detention camp in the LA County probation system. We harness the healing power of poetry and music to build community and create initiatory pathways for young people to step into purposeful adulthood. So, there’s some overlap with what Boysen is describing—rites-of-passage work and homecoming retreat work for people transitioning from one state of being to another and one place to another.

Christopher Henrikson | Street Poets is a nonprofit organization here in Los Angeles that started in a juvenile detention camp in the LA County probation system. We harness the healing power of poetry and music to build community and create initiatory pathways for young people to step into purposeful adulthood. So, there’s some overlap with what Boysen is describing—rites-of-passage work and homecoming retreat work for people transitioning from one state of being to another and one place to another.

Amos | In my practice, I see many men, and I’m always stunned when I asked them the question, “How many friends do you guys have, male friends?” And very often—I’d say 90 percent of the time—the answer is, “I don’t really have friends” or “Oh yeah, I got high school buddies I haven’t seen in 20 years.” Have the lives of men become more narrow socially? Are you seeing that?

Christopher | That’s happening. And then the opposite is happening too. The box that’s “traditional masculinity” has begun to break down and crack. There’s much more gender fluidity in our culture now. The old structures, modes, economic ladders, everything is kind of being swept into this current of change. So are those old ideas and old senses of identity around masculinity and male identity.

That said, what you’re describing is very much a reality, especially in a certain generation of men in our culture right now who are struggling to find a deeper sense of purpose. The suicide rate for men in their early fifties in our culture has been spiking in the last few years. So, I think that a lot depends on the age group that we’re talking about.

I work a lot with young men and boys coming into adulthood. They are entering a landscape that is kind of tabula rasa, you know? Those old pathways are not as clear for them anymore. And there’s a gift in that, as well as dangers and challenges that come with that.

Boysen | That was really well said. At The ManKind Project, our “spot” for men has been those men who hear a call at midlife. A lot of the men that come to the organization are in their late thirties or in their early forties. They’re looking out at the landscape. They’re recognizing that all the stories they were told—about what they’re supposed to be, what they’re supposed to do, how they’re supposed to feel, how they’re supposed to hold it together—are all bullshit. Now what? “You told me if I did this, that I’d be happy and successful. You told me if I did this, that I would be a man. It’s not working. I feel lonely and isolated and disconnected from myself and disconnected from other men and disconnected from my kids.” There are a lot of men who come to the work who want to know how to love their kids better. They want to know how to love their wives better. They want to know how to be with their partners better, and they don’t have the skills. On some level, the work that we do at The ManKind Project is like remedial emotional intelligence work:

Boysen | That was really well said. At The ManKind Project, our “spot” for men has been those men who hear a call at midlife. A lot of the men that come to the organization are in their late thirties or in their early forties. They’re looking out at the landscape. They’re recognizing that all the stories they were told—about what they’re supposed to be, what they’re supposed to do, how they’re supposed to feel, how they’re supposed to hold it together—are all bullshit. Now what? “You told me if I did this, that I’d be happy and successful. You told me if I did this, that I would be a man. It’s not working. I feel lonely and isolated and disconnected from myself and disconnected from other men and disconnected from my kids.” There are a lot of men who come to the work who want to know how to love their kids better. They want to know how to love their wives better. They want to know how to be with their partners better, and they don’t have the skills. On some level, the work that we do at The ManKind Project is like remedial emotional intelligence work:

What are you feeling, man?

I don’t, I don’t know.

Well, how would you know what you’re feeling?

I don’t know.

What sensations do you have in your body?

I don’t know.

I have two teenagers. Tabula rasa is a beautiful way of saying it—it’s a blank slates to a degree. What I notice about teenage boys, especially, is that they are saying, ”Wait a minute. I’m still seeing all of these images in popular media of the tough guys and what it’s supposed to look like. And maybe it looks different than it did in the 1980s, but there’s still a lot of imagery out there that says I’m supposed to be this.” And on some level, we still don’t have a fully human vision of boys and girls, young men, young women, where we can all just embrace every aspect of ourselves.

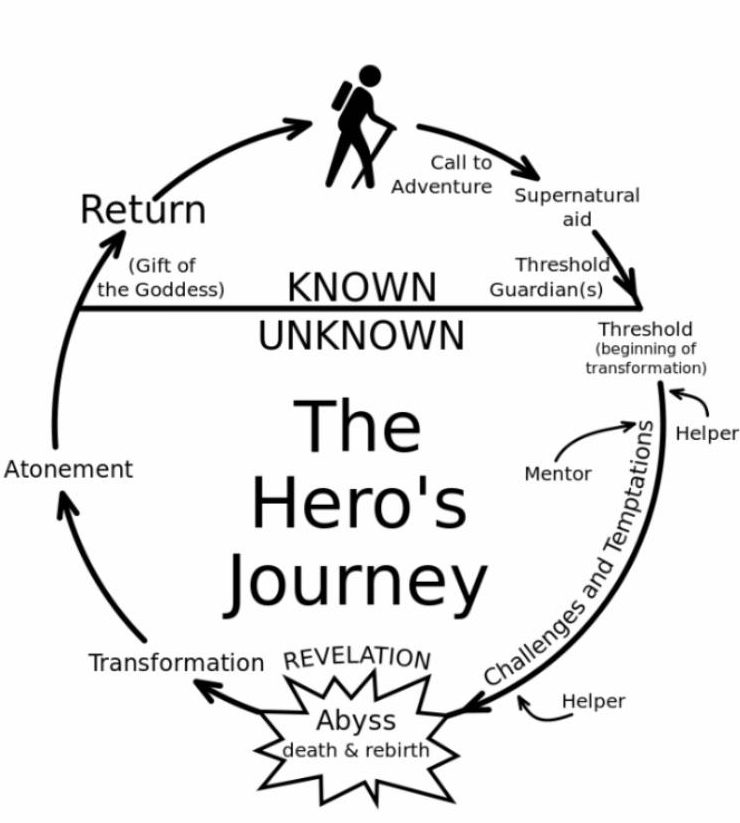

Amos | You have both mentioned something interesting—that transition from boy to man. Why are initiation experiences essential to the transition from boy to man, or from midlife to elder?

Boysen | I think that liminal spaces give us permission to stretch outside of limitations that we’ve had, right? The trainings that we do in The ManKind Project remove you from your normal life and put you in a space where there’s a lot more heat than you’re probably used to, and then we see what happens with all of us together. We get permission to go deeper into our bodies and deeper into what’s going on with us than we might usually get. I think ritual is essential. And what Chris was saying about the transformative power of music and poetry and ritual—100 percent.

Christopher | I would add to that too. I came to this work through the portal of working with incarcerated youth and incarcerated boys, most of whom were gang affiliated. What you see with gangs is an attempt to fill a void in our culture, especially in inner city communities. It’s the only thing that you see there in terms of initiatory pathways for young people that has any structure, except that it doesn’t initiate them into adulthood or purposeful adulthood. It’s initiating them into a form of death or self-destruction.

What I realized was that in order to help someone transition out of gang life, their psyches needed to be engaged at that same depth level they engaged with when they were brought into the gangs in the first place.

And “death” is an essential element to that process. And I’m not necessarily speaking about literal death, although in some cases its presence is a part of that initiatory journey too.

I realized that I was trying to create a doorway for them out of a place that they had gone—you could call it the underworld; you could call it some kind of deeper, darker place. Poetry is one way to bring death and all its metaphoric and symbolic dimensions into the mix and into the conversation. For example, “What in you needs to die in order for you to continue to live in a bigger and broader way?” That question, to a teenage boy, is gonna get his attention.

Our culture has this profound baked-in fear of death because we have forgotten these rituals and these practices through the years. And we’ve forgotten how to bring death into our conversations, into our community spaces, and into our initiatory spaces in a way that opens up the potential for transformation.

Amos | I’m really struck by the Hero’s Journey—that in order for you to be able to grow into the hero you’re meant to be, you have to leave the ordinary world, right? Whether that’s the gang or that’s the work life of a 30-year-old. Then bringing death in, you know, killing off a part of yourself becomes…resurrection.

Amos | I’m really struck by the Hero’s Journey—that in order for you to be able to grow into the hero you’re meant to be, you have to leave the ordinary world, right? Whether that’s the gang or that’s the work life of a 30-year-old. Then bringing death in, you know, killing off a part of yourself becomes…resurrection.

Boysen | And it’s not just death longing. That’s one, right? There’s the birth longing. The mother longing. The God longing. The father longing. Right? And bringing all of those into a place where it’s like, “Okay, you wanna create that? Good. Let’s create that right now, and bring that into the space.” And I think that’s the cauldron of ritual work, transformation work.

Amos | When I say the term “sacred masculinity,” what does it mean to either of you in the context of the work you do? Is this a useful term? Does it divide; does it unite? And what role has the sacred played in your own transformational experience?

Christopher | The word that comes to mind when I think of sacred masculinity is protector. And the image that comes to mind is of a tree, like a sentinel protecting the village, protecting the community, protecting those things that we think of as sacred and that need protection, that deserve our love and protection. What are the things at the heart of life that need to be protected? Sometimes, in our current culture and cultural dialogue, we lose track. For me, being somebody who stands up for justice, for what’s right, and taking care of those around us is a really essential aspect of that.

Boysen | Beautiful.

I did some etymology research, which is a fun place to start. Latin: sacer—to set off, to put boundaries around; sacred—something that is boundaried. That within here is sacred; outside of here is not. The “sacred masculine” idea of it is sometimes really difficult for me to chew on because I’m a heady guy, and I’m a modern man…. What is sacred? What is this?

But what I know is that it’s in those experiences, it’s in that liminal space, I feel something, right? There’s a bodily-felt sensation in this experience of sacred masculinity and the experience of sacred femininity. It is set off from everything else. It’s different. It’s a different space, different time.

And—yeah, I’m bringing God into the conversation—Robert Bly talked a lot about verticality—that something that was really missing in our culture was grounded into the deep earth, into the mud (Jungian, shadow work, archetype work), and connected to the vertical expansive, infinite, possible. That verticality has sacredness to it. So, though I have no belief in a God, I have a belief and understanding and felt-sense of something sacred.

Christopher | And it may be just for me—the sacred masculine has an aspect of fire to it. And in our culture, as you know, we have too much fire. There’s so much violence and addiction, and these things are indicators of fire out of balance or control. But when we think about what fire looks like in balance, it’s that vertical fire in the center of the village that warms everyone, the fire through which we connect with each other, to those who have passed, to our ancestors.

When I think about sacred masculinity, it’s that kind of ritual fire at the heart of the ritual space or liminal space.

Amos | How would you say that the work you’re doing, serving the emotional needs of men, how does it ripple out? How does it impact society at large? And what roles beyond, you know, breadwinner and warrior are you putting forth as another color to paint with in the palette?

Boysen | Um, lover. Nurturer, magician in the kind of Jungian archetypal sense, alchemist.

Christopher | Healer.

Over the last 15 years or so, I’ve been up maybe nine or ten times to Mendocino, California, for the Mosaic Multicultural Foundation Men’s Retreat. Michael Meade is the chief convener of that, and the late Malidoma Somé, Jack Kornfield, Luis Rodriguez who’s a poet and an elder in our Street Poets community, and many other wonderful men. One of the things that comes up every year is how the women in their lives, when the men are preparing the retreat, get a little anxious, like, “What’s going on?” They want to know. But the men who return year after year say their partners are now like, “Go, go.” They’re like kicking them out the house.

Because they know that when they come back, they’re gonna be more present. They’re gonna be more grounded. They’re gonna be more connected to their hearts. They’re gonna be more able to show up for their partners in ways that are more compassionate, more tuned-in to their own sacred feminine as well, and to the creative sides of themselves and their full dimensionality. So, I think there’s a massive ripple effect that men’s work, in general, can have on the culture as a whole.

Boysen | We do homecomings after the New Warrior Training Adventures where we invite friends and family. And there’s a period of time when we ask partners and friends and family to stand and say something about what has happened when their man has gone through this experience. Wives and partners come and face the man who went off into the woods for this experience to say, “When you came home, I looked in your eyes and there you were! You were there. That’s the man I fell in love with. That’s the man I knew you could be, that got lost so long ago.”

My wife knows who I am. She knows when I’m here. And she knows when I’m not. Doing men’s work helps me be here.

Amos | How do you incorporate a wider palate of what it means to be a man into your work?

Boysen | Continuing to grow and change. It’s a very alive conversation, and I’m grateful. I thought I had a handle on this stuff 10 years ago. No way. The amount of evolution today and how fast it is moving, I come back and keep saying, “Oh my God, I used to think that was fixed. I had a perspective on that.” Now I look out and it’s like, “Wow, I don’t have to have a perspective on that.” It’s being created right in front of me. It’s being created by 14- and 15- and 16-year-olds right in front of me.

Christopher | The metaphor that we work with a lot at Street Poets is that of a river, a rushing river. Whenever you’re in the rapids and you try to grab onto things or keep things the way that they’ve been, it creates more suffering generally. A lot of my personal practice and the practice of our community has been a practice of letting go of old ideas, old ways of looking at things and surrendering to the flow of that river. Allowing new ideas, new ways of showing up in the world to present themselves and to be open to learning from them.

The fluidity that exists in the culture right now around gender identity, and really in almost every area, has been an ongoing practice of surrender and staying open, curious about where we’re headed as a humanity.

I think we all know on some level that radical change is necessary in our culture in many ways and many areas. And evolution is something we want to invite in. So, part of that is just keeping our hearts and ears open to what new information is presenting itself.

Amos | I love that image of the raging river, and it actually leads me to the next question. Our screens right now are filled with horrible images of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, right? You can’t avoid it, and that’s sort of, you know, masculinity run amuck. Chris, you were talking before about the fire out of balance—being used to destroy. Does authoritarianism and its rise in the world reflect an imbalance in masculine energies?

Christopher | Yeah, absolutely. I think you’re seeing shadow masculinity.

Fascism, authoritarianism is masculinity run amuck. War and the military industrial complex still, in many ways, dominates the physical world. One way of looking at it is it’s in its final death throes on some level. At least that’s the way I’m choosing to look at it.

But let’s hope that those death throes don’t kill us all, right? There’s the potential, anytime you’re dealing with the kind of change we’re dealing with, that those forces are gonna rise up more strongly than ever and surface so that they can be addressed, dealt with, and seen more clearly.

We’re seeing some really obvious examples, both in our own leadership in the past six, seven years and clearly in the Russian leadership and other governments as well. The rise in fascism is a symptom of something that needs to be surfaced in order for us to address and transform it. But I’m not sure that means that Putin’s going to go through some magical transformation himself on a personal level. It may be more about what happens beyond him.

Amos | We’ve had a very fractured American society during the last six or seven years. How do you guys incorporate different political views into your work?

Boysen | With great difficulty is what I would say. I think that the pandemic has exacerbated that problem a lot. I’ve sat with men who have wildly different political views than myself for many years. And being in the pandemic, I haven’t been able to sit in a circle with these men and really sense them. And so what am I left with? I’m left with my head games. I’m left with my stories. I’m left with the echo chambers of the kind of news and media and messages that I get. And they’re left with the echo chambers of the kind of news and media they get. And then out of all of that beautiful Jungian shadow work, we’re projecting it all over each other—making one another “bad,” making one another “evil.” Men have hardened me into perspectives that I don’t even hold. And I’m sure that I have hardened them into perspectives that they don’t even hold. Schizogenesis is the word for that, right? We define ourselves in opposition to others.

Christopher | I’m going back to that river and fear—there’s a lot of fear in our culture right now. And, whenever fear is on the rise, it’s natural to reach for black and white answers and even authoritarian leaders who say they have all the answers. It’s important to have compassion for people who make choices ruled by fear. Some of my fear may be reduced because of the people that I’m surrounded with on a daily basis and have intimacy with. Other people don’t have the luxury of being in those same circles and spaces. Boysen’s absolutely right—all of these things have been exacerbated by our isolation from each other over the last couple years and our dependence on things like social media, sadly, to figure out how and what we’re supposed to think.

Amos | For many years, I’ve been an advocate of National Service. So that the kid from, you know, Compton gets to meet the kid from Nebraska. It doesn’t necessarily need to be toward the military; it could be planting trees. It could be visiting old age homes. But the notion that you’re giving up something for the broader society could do a lot. I don’t understand why this country doesn’t have it. It seems like something that everybody could agree with.

How about a little bit of a different tack here? I think you are both familiar with my work exposing sexual abuse in the world. How have the abuses in private schools, academic religious schools, the Catholic church, the Boy Scouts impacted the men you serve? What’s being done at your organizations to protect men from these abuses? And have you noticed a change in, let’s say, the last 10 years where people are actually speaking about it more? Has there been a shift?

Boysen | I see Chris nodding also. Absolutely. And what I see is a growing willingness over the last couple of decades for the many men who have experienced childhood sexual abuse to come forward in a way that they hadn’t before. And I think that opens the possibility for more men in our culture to believe women and to hold a compassionate perspective for what they’ve gone through. It also brings more accountability when men are no longer denying and hiding the things that happened to them or the things that they did. It creates more accountability in the culture, which, I think, is what we need to break through.

Christopher | Big yes. To everything you just said, Boysen. And yes to your question as well, Amos. The de-stigmatization of the childhood sexual abuse wound in males, particularly, is something that has been dramatic and continues to be a sign of really positive change in our culture over the last 5, 10, 15 years. Working with gang members here in Los Angeles for the past 25 years, that’s been the final threshold kind of wound in terms of the transformational journey for a lot of them.

I would be shocked if it wasn’t something close to 75 percent of them who have been abused sexually as children or, in one way or another, had that boundary crossed.

And it’s rare that they’re able to begin unpacking that until, in my experience, they get into their twenties. It’s a very unusual teenager who can start to unpack that when they’re still in that hormonal shift and struggling to figure out their sense of identity. So, in our experience, it’s folks that we’ve worked with for 10 years, maybe since they were 14, 15, who begin to get around to that layer of themselves in their mid- to late-twenties.

I think as a result of the work that people like you have been doing, Amos, to shine a light on these larger incidents, it’s actually opened the door for people at a younger age to begin to talk about this. And more high-profile folks are speaking about their own abuse. It feels like things are shifting in a really positive direction there. So it’s something we can feel good about as a culture, I think.

Amos | Yeah. Thanks for saying that. In terms of your statistics, that’s really young for them to be talking. The average male, if he speaks at all, and this is statistics, is usually in his fifties.

Christopher | Wow.

Amos | And women, in their forties. My hope is that that goes down too, very soon. That’s why the statute of limitations laws were so outlandish and draconian, because they would end after somebody turned 21 in a lot of the states.

Christopher | When you’re working with brown and black males who have come with a gang background, it may be a matter of life and death whether they talk about it. It gets to a point where it’s like, “I’m either gonna die or spend my life in prison behind this stuff if I don’t apply these principles I’ve learned in the beginning of my healing journey to even this wound as well.” Because of the culture that we live in and the imbalances in that culture, there’s an urgency that exists, I think, in some of the more traumatized black and brown youth and young adult males that isn’t necessarily the case with these older white males who might still be able to function in society to whatever degree. It may take those white males until their fifties to recognize, like, “Wait, I’ve gotta address this.” And maybe it’s their first glimpse of their own mortality that begins to activate that awareness. Sadly, many young brown and black males in our culture, they’re confronted with their own mortality when they’re 10, 12, 13 years old. Death is already in their face. I think that difference may inform some of those statistics.

Amos | Interesting. I hadn’t looked at it that way. I don’t have the numbers in front of me, but that makes sense. What’s the most important message about masculinity that families, women in general, kids, and society need to hear?

Boysen | Some women in our culture, even though we all know that men are whole human beings and that men have emotional lives and depth and that men have vulnerability and fear, would rather die than see them knocked off the white horse. It’s terrifying for them to imagine a world where men are not rigidly holding themselves together and stoically pushing through, sacrificing themselves, right? It’s a scary proposition to say, “Oh, men are actually fully human and vulnerable and loving and nurturing and soft and tender and tough and strong and willful and aggressive and all of these things.” So that’s one that I think is really big. Lower the barriers, and allow men to come down off of those pedestals so that we can actually be here together.

Amos | Chris, how about you? Who are these teens-to-men, and what needs to be known about them?

Christopher | We talk about men and women, masculinity, femininity, the sacred masculine, the sacred feminine, and need to recognize that we all have all of these in us. So you can be a woman who’s very connected to her sacred masculine and shows up in the world very much that way. And vice versa, you can be a man who’s very connected to his nurturing, creative spirit. The more we begin to take it out of that binary place and into this more fluid place, following the lead of our young people is good. What does it mean to show up in a healthy, masculine way, and what does it mean to show up in a healthy, feminine way?

And that those things are not necessarily connected to the bodies into which we were born but are more about aspects and dimensions of our being. You can look at the Hindu gods and deities that have aspects of both masculine and feminine and show up in both ways. And in a lot of Indigenous cultures, the gatekeepers of ritual are the members of the community that are “two-spirited”—that have both aspects. So I think that’s where we’re headed.

And I have enormous respect for the work that The ManKind Project does. I’ve known many folks that have been beneficiaries. The vision and scale of The ManKind Project is remarkable to me. And important in a culture that has forgotten a lot of these things. So, thank you.

Boysen | Thank you, Chris. I’m just getting to know the work you do with Street Poets. Poetry and music—I don’t think there’s healing without it.

Amos | Thank you both.

Back to Earth

There is a place in between

What you and I call reality

Where a fire burns

Rainbow bright

Even in the darkest night

Rattles dance

Nature’s masquerade

As we offer old pains to the flames

There are names that we’ve forgotten

A language we’ve lost in our journeys

Into blame, seeking fame

We cast spells on ourselves

That erase our ancestors’ trail home

So I bury my roots here

Where four seasons circle the sun

Where leaves change colors

Where grass can be green or golden

The wind blows and the rains shower

Where the land provides

For all that give back to it

For all that are willing to take

Only what they need

Deep blue oceans and lakes teeming with trout

Snow-capped mountains and valleys laced with life

Where you can build a cabin and live in peace

Sip your coffee

Read a good book

Write poems on leaves lifted by the wind

Spinning directions

To reach the lost ones

And remind them

How others can get here

How they too can find a way back to earth

-Jorge Nunez

Former Student & Current Teaching Artist

Street Poets Inc.