Mind and Music

Editor’s note: Andrew Lipke is an accomplished composer, producer, arranger, conductor, vocalist, multi-instrumentalist, and educator active in many styles across multiple genres. He is also my neighbor.

Kosmos | You were a kid in South Africa just before apartheid ended, right? if the trajectory of your life from childhood to now could be characterized by a musical composition, what kind of composition would it be?

Andrew | Well, that’s interesting. I guess it would definitely be varied. There would clearly be a first part and a next part. It was challenging to live in a system that was antithetical to the ways in which you believe humans should interact with each other. Every white family in South Africa had a maid and gardener and so forth. It’s not so dissimilar to this country when it comes to undocumented non-English speaking people doing a lot of the work in all the yards and everything.

But the thing that was very different was that there were all these rules in place where after a certain hour people had to go to the townships or bus out of the city. And that definitely felt – even as a child who didn’t have any other reference, partly because of being brought up in the Methodist church – it didn’t feel right,

I turned nine when we moved in ’87, so in my mind, everything previous to that is a little bit hazy and everything since then is crystal clear. We most often use the word trauma in a negative connotation. And maybe I’m incorrect in thinking that there are other ways that it can be applied. But as far as something traumatic in my life, it was that move from South Africa to America. There was this sort of epic, shattering experience landing in New York City. It was very much like the scene in the Wizard of Oz where she walks out of the house.

So, if it was a composition, there would definitely be a ‘before’ sound and an ‘after’ sound in it – you would know right away which was which.

Kosmos| Whether you’re composing, conducting, arranging, singing or playing different instruments, how do you make your approach to the inherent order, that underlying ‘intelligence’ that is somehow common to all music?

Andrew | I think it’s a combination of two things. The energy part of it, the part that you’re calling the ‘intelligence’ is the fuel that propels the emotional significance that we find in music. That ‘thing’ is ineffable. It’s like God or it’s the same thing to me. It’s that same core magic energy, consciousness, whatever you want to call it… awareness.

That’s really what all music is if it’s honest music. And the less you try to know about it, the better you are. The less you try to understand it in the way that we think about understanding something, the better you are. You want to feel it. You want to practice getting close to it.

There’s a great Philip Glass documentary where he talks about it being like this underground river that you want to be able to access as much as possible. The more you access it, the more natural it will feel. It’s a lot like praying, or meditating. But the more boundaries and guidelines and personality traits and specifics that you give it, the further away from it you get.

All the other aspects that come along with how to use it in order to communicate something, to me, is really just problem-solving as you deal with different genres or different modes of musical expression. The problems start to differ a little bit, but they all start with the same problem and then they start splintering off from that.

The core problem is that you want to convey this thing that’s unconconveyable, right? It’s a feeling, or maybe conveying is not even a thing. You want to capture it. I feel a certain way when this sound hits and I want to capture this and find a way to put it in a little package and say, ‘okay, here’s this feeling that I was able to capture and put in this thing’. And then other people, when they interact with it, sometimes they feel that same thing, and there’s magic and mystery to how that is possible. I don’t know how music works at all. I have some theories about why it can have the effect that it does, but I don’t know how it does. It doesn’t really make any sense.

Throughout my development as a musician, I’ve been interested in so many things, partly because of how they solve problems differently. You have the question of form. If I’m doing something for an orchestra, I have all the practical problems of the individual instruments. Every instrument has a range, every instrument has a tessitura, a place where they shine the best, but then again, they may be really effective in their upper register or lower register, or when they’re really stretched they sound a certain way. I guess through various points of my life I’ve been fascinated by, and curious about what some solutions are to all these various sets of problems.

Cello playing really high feels like somebody’s soul is coming out of their body. And the violin playing low feels like all these different things that are very technical but don’t have anything to do with the music. It’s kind of like comparing the parts of an engine in a car to actually going somewhere. You’re not thinking about ‘going somewhere’ when you’re wondering, ‘how do I get this engine to work?’

Kosmos | Do you sit down at a piano to compose the same way you compose on your guitar?

Andrew | It’s very different. Now you’re dealing with electricity, so it’s a whole other set of problems: What’s the tone? What kind of preamps are you using? What kind of guitar are you using?

I still oftentimes will do things on a guitar and not know what I’m doing, for lack better term. I don’t tune into the theoretical aspect of it. It’s harder for me to do that on piano because I was trained earlier in that, and when I play something, I’m automatically sort of thinking about it theoretically.

I love classical musicians. I write for classical musicians, but I’m not a very good classical performer. I tend to change things randomly, and you don’t want that to happen when you’re a classical musician. However, I love the relationship of written music to music at large. Written music is a completely different way of engaging with those things that we were talking about. Written music fundamentally changes how people think about music.

There’s a lot of discussion about what classical music is or isn’t, and the difference between classical music and popular music. I think the difference is very simple. Classical music for the most part, starts on the page.

Recorded music is capturing a performance, or these days synthesizing a performance, whatever you want to do with it. But either way, you are creating the version of a thing in sound. It’s ones and zeros most of the time, but it actualizes in sound.

Written music – you’re creating a thing that will never actually happen. It’s a soundless music that is essentially just a set of instructions that everybody who plays it will to some degree approach but never land on because it’s not possible. That’s why you can play classical music for two hundred, three hundred years and never be done, because there is no definitive version of the piece of paper. The definitive version doesn’t exist in sound. It exists written on the page. Written music is unrealized.

I enjoy the challenge of trying to figure it out, trying to solve all the problems. The thing I like the most is hearing something that doesn’t exist, putting it on paper and then having it come back and be pretty much what I heard in my mind. That’s the best, that’s the best. And these days I’m able to work with people at a fairly high level where that happens.

If you write it correctly, it happens the first time. And that’s just incredible. Or if you got something wrong, you’re like, ‘oh, that didn’t balance the way I thought it was going to balance.’ But you start getting better at being able to predict that.

Kosmos| You wrote an album called The Plague ten years before we had an actual plague.

Andrew | In The Plague, I found a more unified way of combining all the things I like to do in music. And I really enjoyed that process. Conceptually, it started with two thoughts. There was apocalyptic fever going on. I remember there was a billboard proclaiming the end of the world on May 22nd, 2012 or something. It happened to be my birthday. And the thought that popped into my head was, ‘okay, so the end of the world happens. Well, what do you do then? What’s the next day like?’ What if the apocalypse really happens and we all messed up? Nobody got the religion right? And then the other question was, ‘what would be the practical implications?’ The second song on The Plague, Reunion, is in my mind, this image of two people who feel they should be together but putting it off. And then suddenly it’s the end of the world. They can’t put it off anymore! So, she shows up at his door and she’s like, there’s nothing, this is it. If we’re going to be together, we got to do it now.

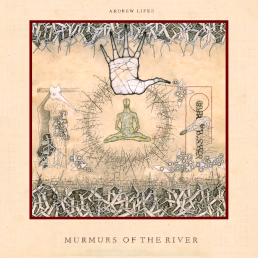

Kosmos| You have seven albums and three of them are based on one book, Siddhartha, by Herman Hesse, (Siddhartha” – released in 2015, “Kamala & The Child People” – released in 2020, and the final installment, “Murmurs of The River”, released in 2021). How did that happen?

Andrew | I read the book when I think I was 18 and I loved it very much, but also had a strong feeling that there were things that I was too young to really mine and get the full value out of them. Later, as I was doing the first album, I was growing in my understanding of classical music. I was finding connections with people who I really respected, who were starting to enjoy my work, which was validating and gave me confidence to be more bold. So, the first album was me kind of going through those processes and trying to bring some things together with some of the choral work that I put in there.

And then my buddy Steve Bradshaw, who actually did the artwork for the first and third album, (he sings in a Philadelphia choir called The Crossing, and we were becoming very friendly), commissioned me to write a piece for them, Fire and the Harp. I said to them, ‘what if this becomes a big part of the second installment of the Siddhartha story?’ And they were totally into it.

So the second album took that 20 minute piece, which I just called Kamala and kind of blew that up into the full album and created a sound world that to me felt like a combination of some of the elements of the previous album and then the dark, nihilistic, destructive energy of the very human existence in the city when Siddhartha is there. I knew that the second act or whatever, was going to be the main part of him having the crisis of Self.

There is a little theme in The Harp that comes back at the end of Kamala and the Child People, that I wrote for my daughter. It’s this one-handed piano thing, because I wrote it while I was holding her and I just kind of played it for her. It’s just a sweet little thing. And it felt like a representation of the wisdom of the child. It’s like those moments when all the things that you’ve accumulated through your life experience…if you’re quiet then this little voice of the child comes up and it’s just a simple thing that still has this profound emotional weight to it somehow.

The third album was definitely written during Covid. There’s one song, And Then There’s Me, that just gets worse and worse and worse and becomes very, very dissonant. I wanted it to have this sort of meta nature to it – the music just can’t keep it together anymore. The whole thing just falls apart at the end. And then the last track, I started playing that song No Other Love, which is actually a Chopin piece that Joe Stafford made famous in the fifties. It’s so beautiful. So, I wrote this violin part for it. It’s like there’s this… kind of just…you don’t need to do anything…

I get into discussions with my father-in-law. He’s very much into Zen. And I think the ego in Eastern influenced spiritual conversations gets a very bad rap. It’s always, ‘lose your ego, rise above your ego, get rid of the ego.’ And it’s not that I don’t disagree with that conceptually, but I think that the ego is wonderful. It’s so important. It’s the thing that makes you want to rise above it to begin with!

You have this piece of God in you and you feel the magnitude of it and at the same time, you also are confronted by the insignificance of your actual existence. You are the One, but you’re also nothing. That’s why I love the word individual – I feel like it has the whole human condition in it. Because you’re an ‘indivisible duality’. You can’t divide the dual nature of the existence you’ve been thrust into, which is you are the whole thing, and at the same time you’re nothing at all.