Wealth as Responsiveness to Earth Wisdom

featured image | Photo by Louis Maniquet

As Turtle Islanders, we welcome you to our lands, but we did not invite you to claim ownership over the land, life, and love that the Earth provides to all equally and freely.

I have known many Native peoples and have witnessed different telluric ceremonies through cosmic observations and respectful syncretism. We, Indigenous, must demand to ameliorate humanistic ideas beyond the normalized perfunctory nod and anthropocentrism of the West.

Occidentalized societies must understand their origins and reckon with the consequences that others have had to endure. The concept of duality, which pits humans against Nature, has led to the exploitation and commodification of the Earth, often justified by Western monotheistic ideologies. It is crucial that we recognize these issues and recognize that these ideologies are not sustainable and equitable when searching for relationships with the living world

I’ve been asked how I can live in two worlds, one of modernity and one of ancient thinking. I’m one Lakota living in one world. The modern world would call the ancient, especially, Native people as primitive and out of touch with modernity.

In the visceral context of Lakota there are no “opposites”, meaning without dividing. If you placed two mirrors in front and behind you, and slightly turned one there would be the vanishing point emphasized in the language of no opposites.

(I hope that makes a little more sense).

The “between worlds” ideas would only conceive thoughts of cultures clashing, worlds different in duality, resulting in winners and losers. Between worlds is neither divided by light nor dark, good and evil, nor exclusion or inclusion. It is neither a place nor an extreme limitation-defined existence where you live or perish. It is a place of liminality, an unknown, for the sake of humankind’s attempt and persistence to possess it. It is without light and dark and connected to eternal continuity, seeding in a place of mystery.

The wise thought-keepers of the Lakota have descriptions that encode such thoughts and cannot be slowed in their journey from eternity to eternity. Where no human being can live is where accounts remain within the language, never to be replaced with subjections of turmoil or objectification. It is called a ‘sacred space,’ a ‘holy place’ where there is no beginning and no end but only continuity.

The respectful syncretism of mystery and origin is not the grumble of Lakota cosmology but the consternation of a Western identity crisis perpetuated by disconnection to the wiser elder — Earth.

The untapped abundance of Native people’s contemplation and consciousness is a daily reminder to speak to a world that has forgotten its origin by the anthropic principles the Western mindset touts for all humankind.

I have witnessed, participated in, and performed different ceremonies, cosmic observations, and respectful syncretism in my short lifetime. I have a small inkling of how, when, what, who, and where has the truer key. I do this explanation within the mind and language of discrimination I’m writing in – i.e. with English – and its perceptive duality and binary concepts. This is a disclaimer: being neither a shaman, medicine man, spiritual interpreter, space cadet, chief, guru, or academic scholar.

Immemorial Dimensions

In the context of many Indigenous peoples, I have experienced and gently given a trusted question without expectations that usually was considered (to sit with the stars) by traditions that are not antiquated but even more modern than academic jargon of duality looking for an exit strategy. The self-torture of misused language is likened to badly used energy – language is energy.

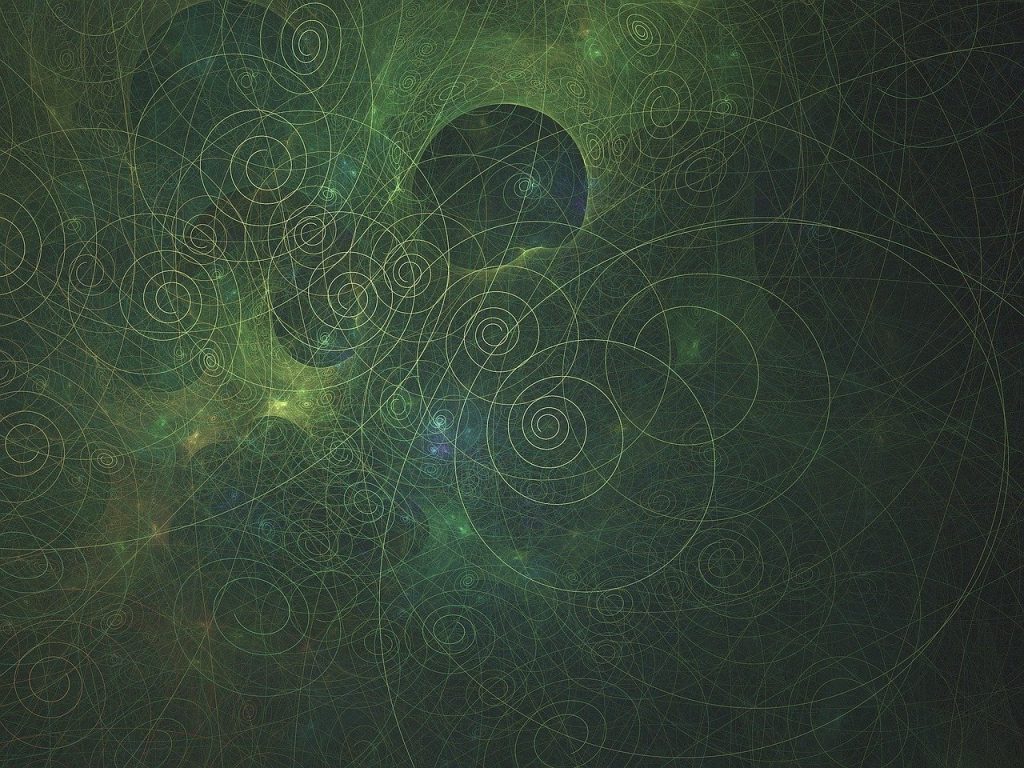

I hear that energy cannot be created or destroyed, and the pathological gist of continuing in the dualism is repetitive, like a circle. A merry-go-round.

The spiral reality surrounding the center comes from intuition, which is not bound by consciousness or limited by words. It is about accepting the pure energy, known as wakan, without trying to solve the mystery. However, the definition of “pure energy” is a spiritual concept that is not yet fully understood.

Many Indigenous people’s languages are encoded with quantum physics within their respective frames and logic. I offer the idea of standing between two mirrors facing each other, where you can see countless images of your original image.

Takuskanskan is a word with a non-conceptual meaning of energy behind energy, behind that energy, followed by energy, and so on, forever. Here is where the evolution of no opposites is imagined and lived within many Indigenous languages.

Other ways of knowing and being

The process of unlearning will take patience, and relearning differently is vital, but we should not relearn in the same way as we learned within the Western process of reductionism and possession. As an Indigenous person learning what money represents and the dazzling world of materialism often leaves me in a quandary of how humans behave in the possession of money.

A strange behavior that drew me away from what it meant to become a natural human being. We were free before freedom got in the way.

I often find myself explaining what it was like being raised on the Cheyenne River Lakota Reservation in South Dakota during my formative years. This excerpt from an article, The Struggle For Our Homes, by Don Fixico (Shawnee/Sac and Fox/Muscogee/Seminole), highlights how Native people have been severed from our original ways and alienated by modernity:

“Many people are familiar with Erik Erickson’s work in developmental psychology, in which he contended that human development occurs in eight “psychological stages.” If raised in a positive, healthy cultural environment, the individual learns – trust, autonomy, initiative, and industry. During the teen years, a sense of identity is developed. Finally, at various points in adulthood, the individual learns intimacy, broadens his or her vision to include the rest of humanity and the next generation (generativity), and develops integrity.

Few know that Erik Erickson (15 June 1902 – 12 May 1994) based his work on the Lakota and the Yurok of northern California, which he chose because of their widely divergent environments in which they lived. Unfortunately, …the disruptions wrought upon Native cultures today too often result in the worst of Erickson’s stages. Modernity [introduction of money] and Western colonial conditions breed mistrust, doubt, guilt, inferiority, and role confusion.

Erikson stressed the role of environmental and cultural factors over biology in human development.

In 1921, very few had even heard of the word culture. Today, it is in everyday vocabulary. Yet, for all the awareness, there is still woefully little understanding of just how radically different Native cultures are from the dominant [society] that surrounds them. These differences lead to very different attitudes toward the natural environment, and it is these differences that make the work … important as a preliminary matter in any understanding of Native perspectives on environmental justice.”

Egonomics – Economics

As I was thinking about how to present these ideas emulating from an Indigenous person’s non-conceptual thoughts, I thought how different it could be if Indigenous languages were not lost-in-translation. Although there have been some gains in academia, philosophy, historical and present-day thought practices, etc. the ideas of Indigenous thinking can only go so far in codifying meanings into the standardized Western mechanics of hierarchy and linear definitions of existence.

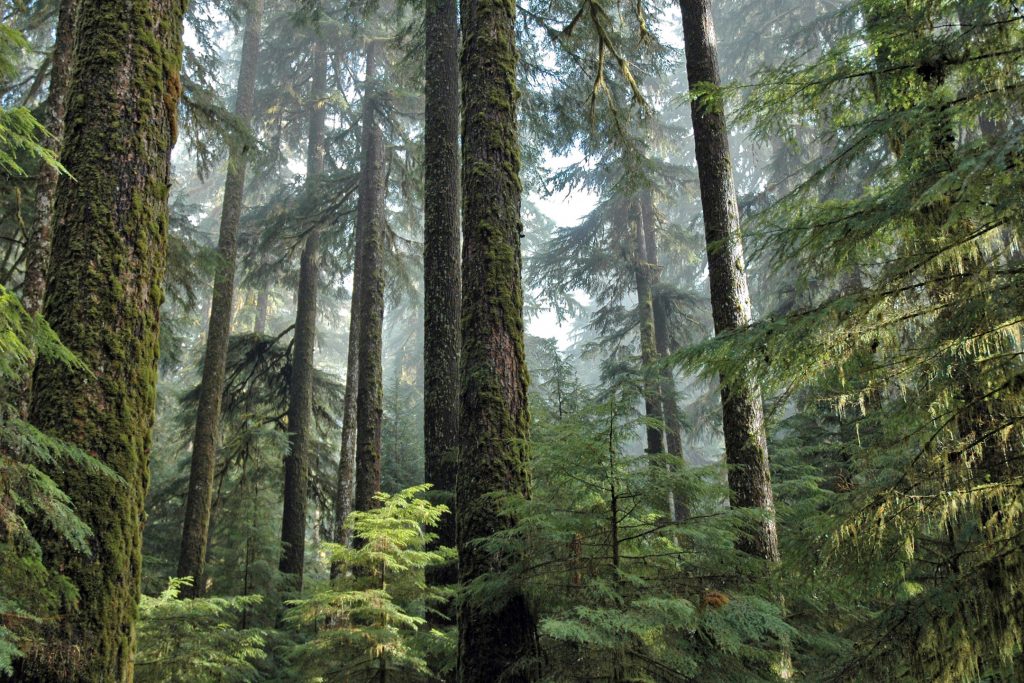

Take for example the overused statement “It takes a village to raise a child” as opposed to the never-heard statement, “It takes the land to raise a child.” The latter includes ideas concerning natural conditions, ethics, and protocols based with the Earth communicating and informing cultures about living reality rather than producing, using and practicing reality.

Most of our knowledge has nothing to do with money. Only recently are Indigenous peoples learning what it means to want. Most of our living has to do with keeping history within the context of the present living cultures, where evidence is not recorded but passed through oral relationality. This requires different research or learning experiences, as mine has, in a word, different ethno-philosophies.

Re-imagining wealth demands that we become knowledgeable about an older way of living without the invention of control and domination. And, also, to see the consequences of the do-gooder mindset and the search for solutionism, and then, alleviation from consequence of reactionary solutions that never address the root cause.

My experience has been that Western thinking has a premeditated ignorance when it comes to Indigenous philosophical thought. Native peoples are included but, at the same time, marginalized and considered outside the realm of Western logos, making it difficult to discuss. “Out of sight, out of mind” means the West has not recognized what a late friend, Jerry Mander, writes in The Absence of the Sacred: The Survival of Indian Nations: the loss of life and cultural heritage among Indigenous peoples has made it challenging to maintain a lively cultural philosophy. The lands are missing when it comes to raising a child, but that will change and is already changing.

Let us close with a story. One I heard many times and that has informed this article.

A Western cultural anthropologist was visiting a village in Africa. He pondered how he would befriend the young children intrigued by his strange clothes, hat, and shoes but were also afraid of him. The anthropologist thought he would involve the children in a little running competition. He went to his food cache, found sweet fruits, bananas, oranges, apples, and grapes, and placed them in a basket at the bottom of a large tree. The 6 to 9-year-olds were told that if they were to line up, the first one to make it to the basket would be the winner and have all the fruit.

The young children looked at each other and stood at a line drawn in the sand. The anthropologist would lower a white handkerchief, and the race would begin, culminating in a winner. He raised his hand and quickly lowered the white cloth and no one dashed from the line. Instead, the children joined hands and arms and walked together, arriving at the tree as a cohesive whole. The oldest passed the fruit to each of the children.

The anthropologist was curious and thought the children might have misunderstood his instructions. He approached the children and asked why no one ran to the tree to win all the fruit. One child turned toward him and answered, “If one child is unhappy, we all be unhappy.”

Perhaps we have to unlearn our notions of charity, justice, money and philanthropy. Perhaps true wealth is an epiphenomenon of the ecology and of the village.