The Practice of Liminal Dreaming

Kosmos | What is liminal dreaming and how is it different from the more well-known lucid dreaming?

Jennifer Dumpert | There are two dream states that, together, make up liminal dreaming: hypnagogia and hypnopompia. As you fall asleep at night or into a daytime nap, or struggle to stay awake when you’re exhausted, you pass through a hallucinogenic, psychedelic, swirling realm that feels partly like dream and partly like awareness. That’s hypnagogia, the kaleidoscopic, free-associative dream state that artists, scientists, and thinkers of all sorts harness for various purposes. In the morning, you surface from sleep through the swimmy realm of hypnopompia. Lying warm and cozy in your bed as you slowly awake, you might notice that something that began as a thought has become a dream. Memory shifts into story as your mind sinks back into dozing and you realize you aren’t actually as awake as you thought you were. Then you know you’re in hypnopompia, the twin of hypnagogia.

The word “liminal” comes from the Latin word limen, which means threshold or doorway, places that are simultaneously both and neither, in the same way that the doorway is part of both rooms and yet is also neither room.

In hypnagogia and hypnopompia, you are both awake and asleep, while also being neither. In a liminal dream, you straddle the dream world and the waking world. Because you’re not fully asleep, you can generally maintain awareness of your actual physical environment. You can identify where you’re lying, hear the sounds in the room and know what they are, even listen to and understand nearby conversations. You’re both asleep and awake at the same time, aware of your surroundings yet also immersed in the dream realm of the unconscious.

In a lucid dream, your waking consciousness arises within an REM dream. You have access to your daytime thoughts and memories, and this familiar “you” can take control of at least part of the dreaming narrative and environment. You can fly, breathe underwater, and manifest particular people and places. Unlike liminal dream space, in a lucid dream you’re fully immersed in the dream world, just as in ordinary REM dreams. Your daytime consciousness has managed to penetrate the dream, but remains separate from the circumstances of the waking world. While you can control lucid dreams, at least to some extent, liminal dreams move too fast, present too much material, and are simply too far outside normal experience to be able to manipulate at all reliably. What you can do is maintain detached awareness of what is happening even as you move deeper into dream space. Developing this awareness is how the Tibetan Buddhists begin to train for full lucid dreaming.

Whereas lucid dreams generally feel like the world, only weirder, liminal dream space doesn’t have the same narrative or environmental structure. We all move through the three dimensions of the daytime world with our personalities, desires, and thoughts intact. In lucid dreams, as in waking states, you’re a self “in here” dealing with a world “out there.” This condition breaks down in liminal dreams. Though some liminal dream experiences do insert you into a specific—if weird—place, much of the time there’s no story line, no “you”, no “world” you move through. It’s harder to map your everyday experience onto the whirling kaleidoscopic excess of hypnagogia and hypnopompia because these states feel so unfamiliar.

Kosmos | How did you become interested in dreams?

JD | Dreams have been a major factor in my life as long as I can remember. Childhood dreams have stayed with me more vividly than a lot of my waking memories. Clearly, my mind-body has always been geared that way. But over time, as I’ve learned more about the topic of dreaming, my recollection of dreams and the level of their intensity have increased. As with most things, the more you learn about something, the richer your experience of it becomes.

Dreams offer an entirely different way of experiencing our own minds. Like most people, I find that sort of experimentation irresistible. The urge to play with consciousness is hardwired into the human psyche. Little kids roll down hills and press their palms against their eyes. They spin in circles until the world tilts into an altered state of reality. We all naturally experiment with our experience of ourselves and of the world until we grow up. Then reality hardens and becomes less fluid. Adults still play with their minds, though. We drink alcohol, take drugs, dance ourselves silly, and seek out all manner of mind-expanding experiences, from sweat lodges to ten-day meditation retreats. Whole industries are built on the desire to experiment with our minds—from ayahuasca tourism to amusement parks. (Even the most straight-edge realist loves a roller coaster ride.) And yet we generally ignore the most easily available, safe, legal, free, and effective means available to us to explore consciousness.

Dreaming is the original altered state.

I’ve been spelunking inner realms with dreams my whole life, learning subtle or sometimes not-so-subtle ways of tweaking the experience for different effect, or just paying attention to my night time travels as a way of amping up the experience. At university, I wrote papers about dreams. When I was doing my Master’s Degree, I volunteered at the Jungian Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism, paying close attention to dreams. I started using the city itself as a dream journal. Then I started teaching various ways of working with dreams. Basically, I’ve been interested in dreams my whole life, from childhood. That interest has only grown over time.

Kosmos | How has your practice has affected your waking life?

JD | In the process of exploring liminal dreaming, I discovered a new mode of perception and understanding. I call this mode liminal mind, and it has changed my outlook on life. Hypnagogia and hypnopompia occupy the middle zones between awake and asleep.

Thinking of this space of the in-between as not just a phase through which to travel but as destination of its own offers new ways to see and understand the many liminal zones of the world.

Some of these liminal zones stand between what we might call the real world and the historical or mythic spaces that often occupy the same space. Australian aboriginal people believe that the sacred time of origins, called the Dreamtime, literally overlays the rocks and hills of their landscape. They can slide between these zones, at one moment standing next to a rock in consensus reality, at the next standing next to the corpse of a lizard man in the mythic world of the Dreamtime. Another example is the personal maps of meaning that organize your city, if you live in one. For one person, a corner bar is just a corner bar; for another, that same tavern is almost sacred because James Joyce once drank there. Liminal mind includes the ability to see the actual world we all share, the rock or the corner bar, yet also perceive the imaginal places and associations that overlay these places. Another great example is sound. Let’s say a bell rings across the street from where I stand. The sound waves travel through space, enter my ear, and get processed by my brain. So does the sound happen across the street, inside my head, or in the loop between bell and me? Understanding that relationship arises from what I call liminal mind.

To explore liminal dream space for creativity, try this exercise:

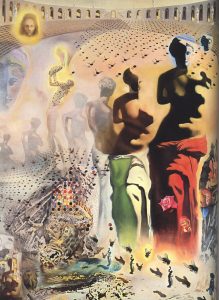

THE DALÍ/EDISON METHOD (FOR HYPNAGOGIA)

Many people have tapped into the creative potential of hypnagogia. Both Salvador Dalí, the surrealist artist from Spain, and the American inventor Thomas Edison conceived more or less the same exercise independently of each other. When feeling tired, each man would sit in a chair holding something in his hands. Edison held balls in both hands, whereas Dalí placed a solid brass Spanish key in one hand. Beneath them lay metal plates placed on the floor. Each would sit in the chair and start to drift off, until the balls or key dropped onto the plate and woke the holder. Edison kept a notepad nearby to write out ideas. Dalí kept a sketchpad. Here’s one way to adapt this practice, though you can find alternatives quite easily.

Wait until you naturally feel sleepy. Thanks to chronotypes and circadian rhythms, most of us experience an energy dip in the afternoon. Just before bed is also good.

Sit comfortably in a chair. If you’re at work, try this at your desk. You can also recline. If you really can’t nap, even lightly, sitting up, go ahead and lie down.

Hold onto something that will clatter loudly when you drop it. You can try holding something over metal plates. You can also hold a bell, a handful of change, or a jingly dog toy. If you’re lying down, just raise your arm in the air.

Keep something next to you to record your ideas. Pen and paper or a digital sketchpad work, as do voice-activated recorders. You can also just dictate into your phone, but set

Drift off into hypnagogia.

Once you drop what you’re holding, or your arm drops, without doing anything else start capturing what’s in your mind.

As always with exercises like this, remember that you’re exploring creativity and generating ideas for yourself. Creativity is not the sole domain of artists, nor is the need to generate ideas confined to academics or inventors. We all hold the potential to make things, to ponder things, and to generate great ideas. Because everyone has access to liminal dreaming, anyone can benefit from these exercises.

From Liminal Dreaming, Exploring Consciousness at the Edge of Sleep, by Jennifer Dumpert, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright ©2019. Reprinted by permission of publisher.

Kosmos | Early in Liminal Dreaming, you share the story of how Thomas Edison and Salvador Dali independently of each other developed practices for using liminal dreaming. Did liminal dreaming prove itself to be a catalyst for certain aspects of their lives?

JD | Many people have tapped into the creative potential of hypnagogia. Both Salvador Dalí, the surrealist artist from Spain, and the American inventor Thomas Edison conceived more or less the same exercise independently of each other to harness hypnagogia for creativity and to generate ideas, a practice I present in my book. It’s a really easy exercise that anyone can undertake to access creativity or generate ideas.

I think that the main reason liminal dreaming opens up visionary possibilities and helps unlock problems is because different modes of thought come together, a kind of two-for-one deal. Most of the time you spend in liminal dream states, you retain at least some semblance of your waking self. The logical, linear, and focused part of your mind remains active to varying degrees. But you’re also dreaming, adrift among intuitive, visual, emotional thought processes and associations. As a bridge between conscious and unconscious mind, liminal dreaming provides a unique opportunity for approaching creative, emotional, and even quite practical questions.

Kosmos | How would you describe the influence of liminal dreaming on the everyday life of someone who takes up the practice?

JD | The influence that liminal dreaming has on those who try it can vary widely, depending on how deeply someone goes into the practice and what motivates them to do it. Everyone is a natural liminal dreamer. We all pass through hypnagogia every time we fall asleep and hypnopompia when we wake, though people who snap wide awake immediately might not experience much hypnopompia. Because we all experience it so regularly, liminal dreaming is extremely easy to learn. Just pay attention as you slide into slumber or coast back up to waking consciousness. That’s probably enough to find the space, though the how-to exercises on www.liminaldreaming.com are easy to follow. Really, though, reading this article is probably enough for most people to have the experience.

Once you learn to locate liminal dream space, you can decide how you want to use it. You may feel satisfied with simply being aware of this marvelous mind state and learning to enjoy the wild ride through your own unconscious. After all, doing things for fun is good for you. Joyful activity promotes good health and happy life. You might also, as I have, really get into it and devote yourself to consciousness experimentation. I use liminal dreaming like a meditation practice, following the ever unfolding moment in the absence of the dominance of my waking ego’s constant grip on my experience, with its expression via never-ending internal monologue. To have a different experience of my own mind fills me with wonder.

You can also direct the experience. I love when people tell me about how they use hypnagogia and hypnopompia. Many people access the visionary space of the liminal dream to amp up creativity to help them write, make art, or solve problems. I wrote a big chunk of one of my most commonly given talks in a hypnagogic dream. People use the practice to deal with insomnia. Learning liminal dreaming changes your relationship to falling asleep so it really helps people who suffer from the inability to easily slip into slumber. I provide a lot of examples in the book for how people might use liminal dreaming in their lives, though I’d say the ones I listed are the most common.