DESCHOOLING DIALOGUES

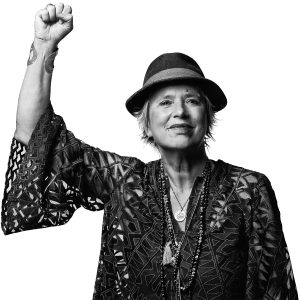

Episode 2 – Alnoor Ladha with V

Alnoor Ladha | Welcome to the Deschooling Dialogues. This podcast is a co-creation of Culture Hack Labs and Kosmos Journal. Culture Hack Labs is a not-for-profit consultancy that supports organizations, social movements and activists to create cultural interventions for systems change. Learn more at www.culturehack.io

Post-production is made possible by dedicated supporters of the Kosmos Journal mission – transformation in harmony with all Life. Visit www.KosmosJournal.org to join.

I am your host, Alnoor Ladha.

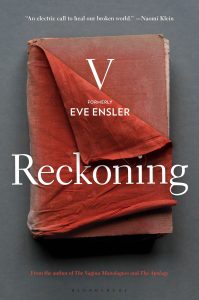

Today we’ll meet with V, formerly Eve Ensler, the founder of V-Day, One Billion Rising, and so many important organizations and non-organizations and movements in the space of social justice and beyond. She’s also the co-founder of City of Joy, which is a physical healing center and space in the Congo. She is the author of Vagina Monologues, The Apology, and her latest book Reckoning just came out. We’re going to talk about that today and so much more. You can Google her and you’ll find out all the things she’s up to in the world and all the relationships she’s been weaving for 30 plus years. Thank you for being with us, V.

V | I’m thrilled to be with you, Alnoor.

Alnoor | Let’s start with what’s animating you and what’s moving you in this chaotic moment we’re in, this bifurcation of late-stage capitalism, what feels like peak capitalism in some ways. And peak patriarchy, peak inequality, peak white supremacy, peak stupidity, and maybe even peak possibility.

V | Yes, I think all of the above. I’ve just come off a three day amazing meeting with One Billion Rising coordinators from all over the world where we meet every year to imagine and create the vision for the risings that will follow in the upcoming year. It’s been an amazing few days. Women from Afghanistan, from Democratic Republic of Congo, from India, from all over.

One of the things that really struck me is this disparity between what happens when we are in community and working together and imagining and dreaming together and the explosiveness of our solidarity and love versus what people are up against when they are struggling in their own countries. This morning, Lucinda was leaving, going back to South Africa, and she said, “I’m full of this love and I’m full of this solidarity and I feel like I’m going back to war.”

I think there’s many people in that room who would’ve said the same thing. And the wars are on many different levels. There’s climate wars, the war against the planet. There’s war against people in terms of racism, the war against LGBTQ, migrants, war against workers. We can just go down the list, but I think what’s really hitting me, and something I was really talking a lot about is so much of my life, I’ve been in the struggle. I’ve been fighting against, I’ve been up against patriarchy, up against White supremacy, up against capitalism, up against imperialism. And I feel like those terms and that way of operating are not working for me anymore because I feel like as we move against the machine and against the patriarchy, they’re still defining the narrative because they’re defining what we’re doing.

Alnoor | The terms.

V | The terms. When I wrote The Apology, which was a book I wrote because I waited for so many years for my own father to apologize to me, for the sexual abuse, for the violence, for the degradation of my spirit, for the decimation of my character, I wrote his apology to me because he was dead, and for 31 years he had never written it to me, but I needed to hear it. I needed the word.

So I kind of climbed into my father and I wrote it in his voice. And he was present for the nine months that I wrote it. And when I was over, the last line of the book is “old man be gone” and my father literally disappeared into the Cosmos and I know he’s in a better place. I know he did a lot of reckoning in his own soul and moved himself out of a very, very, very, very dark zone that he was in.

One of the things I realized is that so much of my life had been guided by my rage at my father, proving to my father I wasn’t the person he thought I was. I would show him and I’d be this or I’d be that, but he was controlling the story. And since the end of that book, that motor that was driving my life to prove to my father, it’s just gone. It’s gone. So what’s happened is I’ve got to create a new motor that isn’t about him, that isn’t about patriarchy, that isn’t about any of these things. It’s about imagination. It’s about the dream. What is the dream? What is our dream? What’s the world we want and how are we going to create it?

And maybe what happens is that there’s this crazy patriarchal post-capitalist falling, broken down world; but alongside it, there’s this other world that we’re creating and it gets to be so beautiful, so connected, so caring, so lush, so fertile, so sexy. So everything is such that everyone’s like, wait, wait, wait, I want to be in this world. I want to be here.

And I think we spent a lot of time over the last few days in our meeting dreaming and asking what are the principles of this new world? What does the new world feel like? What’s happening in that world? And I think it gave everybody so much energy to get out of the fight. The fight, we’re always in the fight. So that’s what I’m dreaming about.

Alnoor | So how did you get to that state? I also grew up as an activist and organizer out of the anti-globalization movement. And when you’re in the face of the oppression machine, when the World Bank is displacing your land or WTO is liquidating your assets and making deals at a nation-state level and all of that, and the corporate state nexus is moving, there’s such a deep sense of helplessness. And what you’re saying is you’re also accessing some kind of non-dual state to hold it in its full shadow, but also hold possibility in its full light. And it requires work in some ways, internally, and maybe we think of it as work-play. Qhat was the process to get there?

V | A lifetime. But also Carl Jung said, “In order to survive in this century, you have to hold two opposite ideas at the same time.” I didn’t used to be so comfortable in the middle.I was an either-or person. And I think one of the things age has done or just evolving as a person, is that this place of… it’s not even ambiguity so much as it’s ambidextrousness, it’s this ability to fly through these different seasons of beginnings and ends and these possibilities of some world collapsing as another world is beginning.

Look, there is plenty, plenty to resist. There’s a lot to resist. But what I feel so much having been on the streets for so much of my life, I’ve camped out, I’ve endlessly protested. We need that. It’s never either/or. But there’s also something else we need. I’ve learned so much from the women of Congo where I’ve spent so much time and particularly at City of Joy, which is this revolutionary center and a sanctuary for young women who have been through the worst sexual abuses. They are shattered when they arrive at City of Joy. But in the process of being there for six months, they begin to get healed and whole.

Look, there is plenty, plenty to resist. There’s a lot to resist. But what I feel so much having been on the streets for so much of my life, I’ve camped out, I’ve endlessly protested. We need that. It’s never either/or. But there’s also something else we need. I’ve learned so much from the women of Congo where I’ve spent so much time and particularly at City of Joy, which is this revolutionary center and a sanctuary for young women who have been through the worst sexual abuses. They are shattered when they arrive at City of Joy. But in the process of being there for six months, they begin to get healed and whole.

And one of the things they’ve taught me is that it’s about energy. It’s about energy. Here they are in the midst of the worst circumstances in the world, but they are singing all the time. They are dancing all the time. They’re moving energy in a certain way that keeps them rising and imagining keeping them deeply connected to each other. And I don’t know, I think sometimes the world can make us feel so despaired, so despaired, like if you just sitting in the room, hearing what’s going on in South Africa, hearing what’s going on in the Congo, hearing what’s going on in Afghanistan right now to women, it’s just mind blowing.

There’s no way to even process what’s happened to women there. The loss of right after right after right, it’s like those beautiful Matryoshka dolls where there’s a doll inside a doll. A right inside a right, disappearing inside a right, disappearing inside a right till you’re down to literally being inside a room where you aren’t allowed to move or exist. You’re not allowed to learn. You’re not allowed to sing, you’re not allowed to dance, you’re not allowed to become.

I mean, that state of existence is so mind blowing. And we really spent time really thinking about how we got here where their rights have been eviscerated , all the things that created this moment – the imperialism, the interventions, the promises, the broken promises, the betrayals and abandonment. So I feel like there’s some place between this rage, grief and imagination. And I think I live constantly swimming in that sea of rage, grief and imagination.

Alnoor | And how do you access it?

V | I access it through writing and art and creation. I access it through my deepening and ongoing love for the mother and her creation and the trees and the birds and the water and the turtles and everything that is here that she’s created. I access it through my connection to my beloved friends and family and my glorious sisters in this movement, who are really working from the core of their souls for a new world.

Alnoor | That’s what I notice about you, the most, in some ways, that you’re creating embodied cultures. You’re doing it with other people. You’re in the dialogue of: this us-versus-them binary, traditional activism can only get us so far. And yes, let’s hold all the truth and all the pain and let’s put it on the table, and let’s also live into the values of post capitalism of what comes next. And you’re doing them simultaneously. There’s no amputation. It’s like you’re metabolizing the darkness and you’re creating the (I don’t want to call it “new”), let’s say new-ancient-emerging cultures.

V | I look at City of Joy, it’s such a metaphor for me, this place, this lotus. And lotuses are the only flower that seed and blossom simultaneously, that grow from the mud.

And I look at where City of Joy is located in Bukavu, Eastern Congo, where the war is still raging after all these years, after millions dying and hundreds of thousands of women being systematically raped and their bodies destroyed, so much poverty and such profound poverty where Congoleses are living in the richest, most resourceful country in the world, and they literally can’t eat their own food, can’t access their own minerals because all these multinationals [corporations] have come from everywhere in the world to extract and take and move them off their lands. And here is this place, City of Joy, in the middle of all that – a jewel in the midst of so much suffering – and its spinning a new energy and creating a new world.

And around it, there’s this camp of widows of soldiers, and it’s a very impoverished camp, but we’ve now brought them into our fold. They’re part of our web. And a lot of the women in the camp are starting to work at City of Joy. They come and dance with us and eat with us. They celebrate Christmas with us, and now they’re beginning to change. They’re beginning to get this energy that’s coming out from City of Joy.

So it’s really taught me, you forge the diamond with love and care, in the midst of anywhere that’s impoverished, in the midst of anywhere where people are hurting and suffering, and that diamond, it begins to radiate out. It begins to glimmer out. It’s contagious. I mean, the way complaints are contagious or suffering is contagious, joy is contagious. Possibility is contagious. Love is contagious. And so how do we do the outrageous, absurd act of loving more, of caring more, of believing more at a moment that tells us to do the exact opposite. And to me, it’s very Beckett. It’s very Beckett. I’ve always loved Beckett. He’s my favorite writer. ”You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on. “

Alnoor | Do you think that it’s possible, even in the midst of bereft and impoverished culture like the US? We’re sitting here in Kingston, in upstate New York, the former capital of the state, the landing place for the British monarchy, and then IBM 200 years later. A shared friend of yours and mine, said to me, IBM: the internalized British monarchy. It’s the same thing. And it’s destitute here in many ways, culturally, spiritually, and the women of the Congo, and cultures worthy of the word culture, they have dance at their core and they have music at their core, and they have community at their core. Can it happen here?

Alnoor | Do you think that it’s possible, even in the midst of bereft and impoverished culture like the US? We’re sitting here in Kingston, in upstate New York, the former capital of the state, the landing place for the British monarchy, and then IBM 200 years later. A shared friend of yours and mine, said to me, IBM: the internalized British monarchy. It’s the same thing. And it’s destitute here in many ways, culturally, spiritually, and the women of the Congo, and cultures worthy of the word culture, they have dance at their core and they have music at their core, and they have community at their core. Can it happen here?

V | Of course it can happen here. Look, I’ve had such great fortune to be able to have toured this country so many times because I’ve done a bunch of plays. When I did the Vagina Monologues, I probably went to every city in this country. When I did The Good Body, I toured this country. When I did Emotional Creature, I toured. I know this country really well, and I know the people of this country really well. And there is a hunger in the people of this country for a new culture, for principles, for things to believe in. One of the things we were creating this week is the philosophy of rising and really mapping out what are the principles that we believe in as a movement.

What if we have a new philosophy? What if we create a new vision of the world and we have tenets of it that we all agree to?

Alnoor | Do you want to share some of them?

V | One is, do no harm. Do no harm and honor each other’s becoming, honor each other’s becoming. And that means that we don’t interrupt each other’s processes, whether it’s gender evolution, whether it’s artistic evolution, repairing and healing from trauma, whatever it is. I think listening, listening, deep listening, it’s a principle. Radical empathy. Radical empathy. Becoming willing and teaching yourself how to really feel what another person is going through. I think making art and the creation of art are part of everything we do. So it’s not seen as this separate thing the way America has divided it out and made it so insignificant.

I remember when we started OBR, a radical dance movement to end violence against all women, girls and trans and non-binary people in the world. And I was interviewed on this show called Hard Talk in Britain, and the guy looked at me and he said, “Tell me Miss Ensler, what does dancing do?” And I just started laughing and I thought , what doesn’t it do? What doesn’t it do? But it’s this idea of perceiving art and dancing and music and poetry and theater as if it’s some lowly thing that you get to as an afterthought, as opposed to being the center of whatever we are and whoever we are. Because the one thing art can do is break through binaries. It can surprise you and open up your heart and take you out of your mind.

Alnoor | And it’s inherently disruptive because the entire West is based on axiomatic, Cartesian linear logic, which is why art is seen, in one sense, as frivolous. It’s not “productive”. It goes against the Protestant work ethic. But then on the other side, it’s the secular religion of the West. We lionize artists and create these museums and spend hundreds of millions of dollars on static pieces of paper, which is very telling of the Western psyche, to both demonize and lionize the thing it doesn’t understand.

V | I think what America is most afraid of: disruption. I write about it, actually in Reckoning, there’s an essay called Disruption. Because I remember hearing about this town where the people knew they were living next to a poisonous factory that was literally making everyone in the town sick, but nobody wanted to give up their houses. No one wanted to give up their comfort. No one wanted to move, no one wanted to be disrupted. No one wanted to move out of whatever comfort zone, so they were actually willing to just get sicker and sicker and sicker. That is somehow the story.

V | I think what America is most afraid of: disruption. I write about it, actually in Reckoning, there’s an essay called Disruption. Because I remember hearing about this town where the people knew they were living next to a poisonous factory that was literally making everyone in the town sick, but nobody wanted to give up their houses. No one wanted to give up their comfort. No one wanted to move, no one wanted to be disrupted. No one wanted to move out of whatever comfort zone, so they were actually willing to just get sicker and sicker and sicker. That is somehow the story.

Alnoor | That’s the metaphor.

V | It’s the metaphor. It’s like we drug people in this country. We overeat. We’re addicted to everything. The opposite of disruption is to keep everyone anesthetized and numb and sleepy and not believing they have any rights or ability to advocate for themselves or another way of being here. And it’s not accidental that the pharmaceutical companies have made so many drugs and gotten so many people hooked on these drugs. So people aren’t feeling their rage, they’re not feeling upset, they’re not feeling the level of intensity they need to feel in order to question or rebel. So I’m really big on disruption.

Alnoor | Let’s talk about the body. We have not explored the body as a site of revolution, but there’s a lot of parallels between the demonization and lionization of the arts and demonization and lionization of the body. We’ll do anything from the most insane untested pharmaceutical drugs to life-extension machines, to uploading our consciousness to the AI to keep this thing going. And yet we have almost no relationship with it as a dominant culture. And maybe you can say a little bit about the body and your relationship in understanding the role of the somatic experience in liberatory expression.

V | Well, it’s so interesting what you’re saying because I think it’s kind of parallel to what we were saying about demonizing and lionizing. It’s like we do a lot to the body, but somehow the body doesn’t exist. It’s only conceptual. The body is where the real change happens. At a very young age, because my father sexually abused me and beat me,I left my body. It was the the landscape of so much horror and so much pain and so much brutality that I couldn’t live in my body. Anytime I tried to come back into it, there were memories, there were scars, there were beatings there.

So I left and I lived in my head. I remember I wore a hat all the time. It was just to keep my head on because the whole world was there. I was just a head. I had a therapist who once said to me, I’ve never thought of you as a person with a body. And then one night when I was performing the Vagina Monologues, I actually came back into my vagina right there on the stage and I went, whoa.I am in my vagina.

And that was the beginning of a journey of return because patriarchy and that violence had pushed me out of this body. And what’s happening to women country after country is the occupation, raping, decimation, battery of our sexuality and our core energy force. Patriarchy and violence have separated us from our vitality and life force.

I got very bad cancer 14 years ago and ironically it was the thing that moved me back into my body. I know now when I’m in my body, I have the energy I need, I have the vision I need, I have the clarity I need because I’m connected to the Mother. It is body to body. I am her body. She is my body. When they pushed us out of our bodies through violence and occupation, they pushed us out of our own wisdom, intuition, our sense of continuity and community. And that’s what has to be restored.

Alnoor | And in many ways, like the dualism that came out of first, the Renaissance and then, the Enlightenment, essentially said: the mind and body are separate. Mind is superior. Cartesian dualism then translated into all other dualisms. There was us and then there was the other. Then of course the White male Christian was on top of that. So the othering happened to women, to Indigenous people, to Black people, to bodies-of-culture of all types. And it’s not a us versus them thing because it’s physically manifested in our disconnection from our body at a societal level, at a cultural level.

There’s a heretical Sufi line that says: “the body is the prophet.” The reason it’s heretical is in traditional institutional Islam, one would say Mohammed is the last prophet. It comes from actually a triptych, which is: “the body is the prophet, the ummah is the prophet, the desert is the prophet.”

So the body, as you say, is our direct relationship to the Mother, to Earth itself. Pachamama, Gaia, however you want to see it. The Ummah means community. It’s the community of people around you that keep you accountable to those practices. And the desert is the prophet, that is the ecology is the prophet. There is no consciousness outside the living landscape. And that these are three cascading nested ontologies or types of beingness, which is body, community, place.

We don’t have a relationship at a cultural level, at least with either of those three central pillars of a mystical tradition, let’s say, or an Indigenous tradition. So the last question and part of the inquiry of this podcast is: what do we need to unlearn societally, individually, at a community level? However you want to answer it.

V | That we’re separate. The idea that we’re separate from the earth, separate from each other. I think we have to unlearn and refuse hierarchy and dominance. We have to first and foremost dismantle patriachy.

Alnoor | It’s an invented construct.

V | Invented concept. Insane, insane idea. We have to unlearn masculinity and this absurd notion of masculinity. We have to unlearn patriarchy, but it’s even bigger with patriarchy. We have to lift this bell jar of patriarchy that we’re under. We have to literally lift it so we can be free to take our minds back again, to think in a way that allows us to imagine a future. We have to unlearn the fact that there’s not enough for each of us. That there’s only limited scarcity. The fact of the matter is if we were all living in the life of a… I read this somewhere, it was so beautiful, the life of a middle class person in Italy, we could all be living the life of a middle class person in Italy.

For all the resources of the world were divided up, where all the billionaires put all their money into this pot. We could all be living beautiful lives where we had food and water and we went to school and we had healthcare. And imagine this, so we have to unlearn the fact that that’s not possible. We have to unlearn capitalism for God’s sakes, and the system that is crushing us, crushing us. We’re at the apex of it, and it’s just firing on all cylinders right now, of just merciless death and destruction.

Alnoor | We were speaking with Vanessa Andreotti, who wrote Hospicing Modernity, a couple of days ago, and she was saying one of her elders, chief Ninawa from the Huni Kuin people of Acre in Brazil said, “Colonialism is an impairment, an imposed sense of separation.”

This was his definition of colonialism. That it’s a cognitive relational neurobiological impairment based on the illusion of separation. That was his definition for whiteness and colonialism. It’s not racial. If you have been socialized into the illusion of separation, that is the colonization of your mind and body and heart and soul.

V | And it’s actually the breakdown of them because we can’t live in separation. It’s too lonely, it’s too fragmented. It’s really just PTSD. That’s all it is. It’s just trauma, and when you really begin to know that you are every person you meet and everything you touch, then you realize that you don’t really have to exist at all.

Alnoor | It’s enchantment.

V | It’s enchantment. You just surrender to this gorgeous sea of ultimate becoming. I think what we really have to get rid of is the fundamental belief that we as people do not have the wisdom, power, energy to actually reinvent the world or return to the world that we came from. We have that power. It’s just a question of being so close to each other that we are constantly in this ongoing state of collective remembering, Remembering, caring, connecting, becoming, evolving.

Alnoor | Beautiful. I think that’s a great way…I won’t say end because we’re always in the middle, but it’s a good way to stay in the middle with you for now.

V | Okay, beautiful.

Alnoor | Love you my dear. Thank you so much for being with us.

What a powerful, passionate and inspired conversation! I could feel the dance, the song, the fervour of V’s joyful ‘contamination’ stirring so much in my psyche. She pushed me. Disrupted me… and I loved her for it! Thank you for this. I will share it generously with others!