DESCHOOLING DIALOGUES

Episode 4 – Alnoor Ladha with Tiokasin Ghosthorse

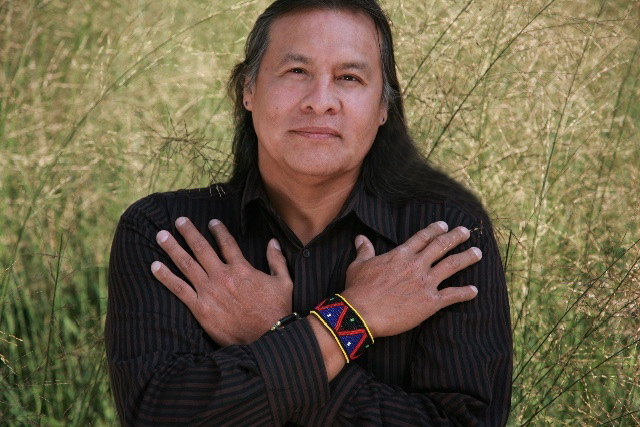

Alnoor Ladha | (LA) Welcome to the Deschooling Dialogues. This podcast is a co-creation of Culture Hack Labs and Kosmos Journal. Culture Hack Labs is a not-for-profit consultancy that supports organizations, social movements and activists to create cultural intervention for systems change. You can learn more@culturehack.io. Post-production is made possible by dedicated supporters of the Kosmos Journal mission, transformation in harmony with all of life. You can find out more@kosmosjournal.org. I’m your host, Alnoor Ladha. In this episode, I meet with Tiokasin Ghosthorse. Tiokasin is a Lakota elder. He is the founder and host of First Voices Radio that has been running for 31 years, the first Native-only radio show in Turtle Island. He’s also the founder of the Akantu Institute. He’s a dear mentor, older brother, friend, ally, teacher and elder. I’m excited to have him here on this episode of Deschooling Dialogues.

AL | Welcome Tiokasin.

Tiokasin Ghosthorse (TG) | Thank you so much for asking me.

AL | We’re meeting here in Kingston in upstate New York. Tiokasin does not live too far away. And I wanted to start with just a general introduction, not the traditional biography necessarily, because I know that would make him uncomfortable, but to ask about the inquiries you’ve been walking with and how you find yourself here in the historical civilizational crossroads we find ourselves in.

TG | Well, Alnoor, thank you for that. And thank you for this honor to be on the Deschooling Dialogues. And I think about this: how do we give praise or credit to that language that controls us? So we say…well, the moon, you were meant to be here like the moon, the sun, and the stars, right? So that’s a one-way street. But from where I think, it’s that the moon, the sun and the stars meant for me to be here. You see? And it changes everything. And I think that’s part of the deschooling, it’s how we perceive this binary language. It’s a destiny, even fate. We have no choice when chance is totally organized.

And so we work out of that spirit of being where we are, being present. I cannot be in the future and in the past at the same time, yet I can be. And that’s where we get the word Akantu: an Earth being in the ancient future now. As far as we know, Lakota is a 200,000 year old dialogue with Earth and where our thoughts come from – the listening underneath from the Earth. And it’s where our thoughts come from because we’re made up of that same composition.

AL | (03:42) Part of the inquiry of Deschooling Dialogues is an acknowledgement of this current moment that we’re in. I know the Hopi would call this the Time of the Sixth Sun or the Iroquois, the Prophecy of the Seventh Fire. And the Vedic tradition would say, this is the Kali Yuga, the Dark Ages. The Alchemical tradition would say, we’re in the underworld now. What do we need to understand about this current context in time? And what habits, practices, behaviors, cultural norms do we need to unlearn?

TG | Well, that’s a good question. There is no beginning and there will be no end to this, to put ourselves in context of being here in a spatial atmosphere, so to speak, not a temporal one. We’re not in rhythm with the Earth anymore. So our languages are not in rhythm with the Earth. We come up with ‘climate change’ and to some people that was caused by racism, it was caused by all these ‘isms’ that civilization came up with.

TG | Well, that’s a good question. There is no beginning and there will be no end to this, to put ourselves in context of being here in a spatial atmosphere, so to speak, not a temporal one. We’re not in rhythm with the Earth anymore. So our languages are not in rhythm with the Earth. We come up with ‘climate change’ and to some people that was caused by racism, it was caused by all these ‘isms’ that civilization came up with.

But when you bring that climate change to Native peoples, we’re going, what is that? It only speaks of being out of rhythm and understanding. We’re still expecting to adapt Earth to our needs, and there’s no contemplation about how much we take from Earth? Are we extracting from the Earth or even learning to respect it in ceremony?

So we revert to ritual and we cannot practice rituals. We have to live ceremony. And so, in this way, ceremony is constantly in the language. I’d say maybe three quarters of Lakota, Old Lakota is ceremonial creation within almost every word.

And when you get to that dialoguing with Earth, you understand that relation, the relational value, of these languages, how we learn. And I like the fact that you’re Sufi because you would understand this: that our values, which I can’t name all numerically right now, but those values we learn in silence. We can’t instruct them, we can’t point at them, but we understand the energy of it and this is how we keep who we are because we know what we’ve learned.

Western society is only a coat or the ‘colonial coma’ as our friend Vanessa [Andreotti] would say. And so it’s up to us to look at this colonial disposition that we all have. We go to the clothing store, we put on the errors of, ‘I have a PhD, I have this and this and this,’ and it works in that world, but does it work with the natural world? Where is the natural being these days?

So when I think about unlearning, it’s easier for me because I come from that base, not something that came on the ships or where I was forced to 2000 years ago, 3000 years ago when all the war happened against the Earth, to begin there by separating humans from the Earth. And so we continue to speak that language. And I think part of that is learning that history, as I have to understand what went on with them, that they had to jump on a ship and bring the pain without understanding the pain.

AL | (07:35) And so partly what you’re saying is, in order to deschool and unlearn, we first actually have to understand the impoverishment of the time and the moment we’re in, but also who your people are, what culture are they coming from? When you say the people who came off the ships, you’re talking about what Steven Jenkinson would call the spiritual orphans of the West. Those who came from Western Europe as part of the conquistador, colonial imperialist project, most of whom were not that themselves, but were the direct frontline troops of the English or the French or the Spanish or what have you. They were the kind of undergrowth, the so-called citizenry pushed to repopulate the badly named New World.

TG | It’s like looking west, and maybe for them it’s the right direction to the promised land, but the path they took was the wrong one.

And so you need to back up on that path. And you can picture this, you can picture this. It’s beyond metaphor, but if you understand the energy of this language that I’m speaking, that we are speaking now, it’s wasteful. The language looks at almost everything as having a waste, a conflict and antagonism at war with itself. Doubt, self-doubt, needs, how do you say, self-esteem therapy.

And so from that viewpoint, we saw the people needing that self-aggrandizement as the language comes from ‘I, me, my mine’ and ours that came over. We didn’t understand that, but we could see it in more of a whole. So we stepped back and watched it happen, and we understood that these people were spiritually starving because they brought religion, science and authoritative stances and everything that they could to come and conquer. Well, now it’s reversing itself. So when I talked about this, how do you say this, immunity.

AL | The auto-immune phase of the Anthropocene.

TG | This autoimmunity, this language, it’s eating itself. And this comes true with Sitting Bull. Now I’m going to repeat what I heard when I was very young, as best as I can. What happened is Sitting Bull saw this thing that he couldn’t figure out what it was…very many little white packages eating the land, and he couldn’t understand it.

And it turned out to be covered wagons eating the land. And it ran out of land to eat. And so when it turned on itself, which its doing now, and I can say the date that I know in my lifetime is 1992. 500 years after this thing, this white package. What eats itself are parasites. What eats itself that we could understand then was maggots. So this attitude, these ideas, this language is eating itself. That’s what I mean by autoimmune language.

AL | (11:40) And so maybe as we’re talking about the kind of unlearning aspect, you could give us a contrast with, for example, Old Lakota. From what I’ve learned from you, Old Lakota is a language based on verbs, on action and is therefore inherently animistic and alive versus the kind of dead, inert language of objectification and nouns and the thing-ification that is in English, in addition to what you said, it is a binary, oppositional kind of reductionist language. But there’s something core to Old Lakota that you’ve spoken about before, which is that the learning and the unlearning and the wisdom is in the very language itself as a living entity.

AL | (11:40) And so maybe as we’re talking about the kind of unlearning aspect, you could give us a contrast with, for example, Old Lakota. From what I’ve learned from you, Old Lakota is a language based on verbs, on action and is therefore inherently animistic and alive versus the kind of dead, inert language of objectification and nouns and the thing-ification that is in English, in addition to what you said, it is a binary, oppositional kind of reductionist language. But there’s something core to Old Lakota that you’ve spoken about before, which is that the learning and the unlearning and the wisdom is in the very language itself as a living entity.

TG | It’s like speaking a commonsense language that misses. When I talked earlier about cultural diversity, well, the reason why we are more or less resilient is that we know where the power, the oracle is. And to walk with that with, as you would say, dignity, but to walk with the Earth beneath your feet, stars above, and these pictures, these ideas that this energy is to understand what we are saying.

So when we speak this language is so that you understand the energy, you describe the energy, then you understand the motion of the energy, and that’s all you need! And that comes without conceptual thinking because it’s the feeling that’s there, that’s present. And when you’re present with the feeling you can see everything. One of the ancestors said, the center of the universe is everywhere. So you have quantum physics within the language that helps you go outside of the box of conception.

The box that I describe as ‘the beginning and the ending’, the superior, inferior, the cause and effect, those are very right-angled thinking or thought processes. And so if you have verbs, it’s always a continuum. And in order to have to be in the continuum, you need the verbs to see where you are in the present always. And to understand the energies are beyond just material, the world realm and the dimensions that we see, you really can see them.

You can listen to the plants, you can hear their music, everything, but you have to be in the language. We just can’t say, oh, I hear plants. And just kind of like tongue-in-cheek philosophies you really can, we’ve known this. We know that trees communicate, we’ve known that before books were written. We’ve known about the mushrooms; we’ve known about this. But that’s the slower learning process. So it’ll be easier for me to unlearn, take the coats off because the process of learning is slow. It’s not like you say quick, you go to class, you got it, you come back for another and then you get your degree saying, you know something. But that’s only survival in this society.

So I think part of that is using this language that we’re speaking less and understanding the energy that we’re feeling that has no expression in this language.

AL | (15:25) Beautiful. Thank you. And another aspect then around deschooling is maybe private property and all of our conceptions of ownership, which are also related to language. ‘Mine me’, is the egocentric language that is sort of core to the Eurocentric approach. Maybe you could say something about the dissolution of these abstract ideas that have so much material influence. Our laws are just essentially built around the protection of private property for a gentry class of historically white Christian males.

TG | Wow. Well, from what I understand of this history of the West, how ownership got here is that we have it now. We have it in our colonized view as native people because we have to survive in it. So everything is moving in that direction. And that’s a loss to cultures of Earth.

Civilizations, you can have the one that I spoke about ‘spiritual civilization’. I don’t know if there’s something like that. There’s religious civilization, but spirituality to me always has culture. The culture of spirit, and spirit defines that culture, and therefore these words are not mine. It’s the message behind that.

Silence again is the biggest decoder, the master of unlearning because you get to feel what you’re thinking, not conceive what you think you’re thinking, if that makes sense. So this is why ceremony is part of that unlearning, as you know. It’s unlearning, seeing, perceiving, not even questioning, because that question deserves an answer, so to speak. It’s that accepting without allowing that answer to overwhelm you like heaven and hell, it’s very dualistic thinking. So it’s silence that’s the biggest healer. Silence is something that is all around. You swim in it every day like intuition. Intuition is the language of silence.

Silence again is the biggest decoder, the master of unlearning because you get to feel what you’re thinking, not conceive what you think you’re thinking, if that makes sense. So this is why ceremony is part of that unlearning, as you know. It’s unlearning, seeing, perceiving, not even questioning, because that question deserves an answer, so to speak. It’s that accepting without allowing that answer to overwhelm you like heaven and hell, it’s very dualistic thinking. So it’s silence that’s the biggest healer. Silence is something that is all around. You swim in it every day like intuition. Intuition is the language of silence.

AL | (17:54) Say a little more about your conception of intuition, because I think this is also of course core to the notion deschooling, right? We’ve formalized our abstract thinking and then we’ve married that with vocation where the entire point of education is to get a job, to be a cog in the capitalist machinery. And so what is the role of intuition as part of our, let’s say, initiation into at least attempts at a wisdom culture.

TG | ‘Common sense culture’, I would say. So intuition, at least to me, my thought process is it’s a being. How are we treating intuition by saying it’s a hunch, it’s a guess. It’s a gut feeling. It’s very disrespectful when we look at it that way or we roll the dice. Intuition already knows where it needs to be. It doesn’t cost anything, right? It’s totally free. And when you’re free, all dimensions are available. And so where’s the language to describe that free? The being-intuition.

And in comes the human being that no longer knows how to be a human being but has become a human doing. That they do so many things that they forget the essence of the silence that they were born from, into, and will go out of this dimension in. It’s to understand that peace with Earth is peace honored and it’s simple. That’s what I could come up with. Peace with Earth is peace honored.

Now to have an answer for you. The spirits have to tell you this. It does not mean I’m a shaman or spiritual guru or anything like that, a medicine person. I’m just a regular being with common sense. And when you’re in that place, when you see the light beyond what you can describe with the words of this language, even my language is that we are out of rhythm with nature so much that we have to call it ‘nature’. Nature, or you say Gaia, I say Mother Earth, which is not really what Maka Ina means. In fact, it’s beyond that description of this language. So we have a lot of work to do to unlearn, to deschool, to un-Westernize. To take Maka Ina again, to unlearn, to wake up from the coma.

AL | (20:42) Maybe this is the last question as I want to honor your time. A westerner saying, okay, well I understand what you’re saying around silence, around intuition, around language, but I need to put food on the table and put my kids to school and play my role in the machinery of capitalist modernity. What would you say to that person?

TG | I would say, how much do you want to participate in giving yourself away?

There is no word for sacrifice [in Lakota] – it is that which gives itself to you – that is sacrifice. We are taught that, again, we don’t lead; we don’t follow, we walk with – which is sacrificing to us. And so we have to always treat that in a ceremony. Everything is ceremony to us. So as a language, and when I think about, yeah, I have to drive a car to get here, I have to have food. And we are taught to ask in this society – basically a beggar’s language, a language of scarcity.

But on the other end is, well, you must speak a language of abundance, that’s not “it”. That’s not the opposite of scarcity. So, it is just what it is. What do you need today? Because the future will always, if you understand today, the future will always be available as well as the knowledge of the past. And I think that’s where we have to decode our own thinking and get away from the ego as you understand- the identity that we’re supposed to have within the survivor language. This is a survivor’s language that we’re speaking. Whereas you can’t speak this way in Old Lakota, you can’t speak a survivor’s language based on fear. And if you consider fear a being, then you also understand how this society understands it. Dualistically.

AL | (22:58) There’s a line that has come to me a couple of times in meditation and ceremony, which is, “trust is the ultimate suicide pact with the universe. You have to be able to stand at the edge of consciousness and be willing to fall and know that you will be caught.”

TG | I love that.

AL | And even the relationship with scarcity and abundance and money, it’s like part of a spiritual practice that I know I will be provided for if I am in resonance with the desires of Mother Earth, Pachamama, the Gaian whole, whatever you want to call it. But that requires a belief in something bigger than you.

Yet institutional religions of the West, the corporate capitalist structures, the political leaders, the media, they’ve hollowed out that relationship. They’ve said, trust us, right? Academia, science, we know the answer to everything. We’ll get the grand unifying theory of everything. Here’s why you’re doing what you’re doing. Here’s where we’re going. Here’s the capital T truth on the human experience in all the ways historically cognitively, neuro-scientifically, physically, metaphysically. And so this monopoly has mediated our relationship with something bigger than us to trust and to be in service to. And that gap requires some bridging. And we’re like these spiritual orphans on one side of this vast chasm with no bridge. And maybe you could leave us with? What does that bridge look like? Is there even a bridge? Is there a way to build that bridge? Is there something we can do in our bodies to start even attempting to conceive of the bridge?

TG | There is no bridge.

If you’re in it and you’re understanding your place, that like you were meant to be here, that sounds so cliche, but Wana, Wana means now. And like we say, Taku Ashka, which means the spirit behind the spirit, behind the spirit, behind the spirit. It’s like dimensional effects that we have. Where does your energy go when you speak? It just doesn’t stay right here. It goes out. Technically this broadcast, spiritually, energetically. It always moves and it always, you identify that if you understand that the continuum, not of time, but the continuum of emotion and energy, that’s where it comes from. So, if we understand that I am not the message, but the message that I carry is bigger. And that’s why I think First Voices Radio is what it is because it’s always been about the message that it goes. And somehow, I don’t see how it kept going with no funding, blah, blah, blah.

AL | (26:03) And you’re not planning for that?

TG | No, I’m not planning for it. I just want to be here because that’s the message, to be here.

AL | And I love that you’re just so direct about it. There is no bridge, but there is an awareness of consequence. And if we are aware of the consequences in the present moment and anchored in the present moment and in place, then we can actually deepen our practice of trust.

TG | Yes, because the Earth trusts you to give to you air, water, food, comfort, all of that. And you see that that overwhelms all the discomforts. And we need to be between those quote ‘dimensions’ or worlds to understand the mystery that it already understands us.

The trees acknowledge us when we walk in the forest. We don’t go to nature. Nature is in us. So we never separate it. We don’t have to build bridges; we don’t have to connect. We’re in relationship, we’re in dialogue. We’re in conversation all the time with everything that we know, atomically down to the neutron is, that everything is alive.

We’ve known that way before Western science came here. And to lose that means that we’re going to have to give up our relationship with nature and the quick fixes that are coming. that are here and now have to be proved, proven by science. And we just kind of sit back because we know that we have the time, so to speak. So patience is one of the virtues that you learn in silence. It’s not taught; you learn it.

AL | Beautiful. I think that’s a great place to end. Thank you so much for your time, for your eldership, for the way you walk in the world and all that you do.

TG | Honored. Honored, always. Alnoor, thank you so much for this. It’s good to be here.