Deschooling Dialogues | Alnoor Ladha with Zhenevere Sophia Dao

DESCHOOLING DIALOGUES

Episode 5 – Alnoor Ladha with Zhenevere Sophia Dao

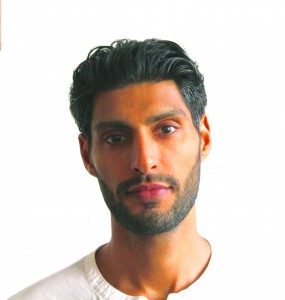

Alnoor Ladha | (LA) Welcome to the Deschooling Dialogues. This podcast is a co-creation of Culture Hack Labs and Kosmos Journal. Culture Hack Labs is a not-for-profit consultancy that supports organizations, social movements and activists to create cultural intervention for systems change. You can learn more@culturehack.io. Post-production is made possible by dedicated supporters of the Kosmos Journal mission, transformation in harmony with all of life. You can find out more@kosmosjournal.org. I’m your host, Alnoor Ladha.

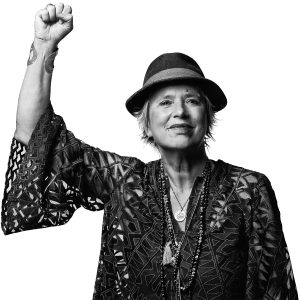

Today I have the honor of being with a dear friend, elder and mentor Zhenevere Sophia Dao. Welcome. Thank you for being with us on Deschooling Dialogues.

.

Zhenevere Sophia Dao (ZSD) | Thank you so much for having me.

AL | I’m going to forsake introductions. You and I talked about this before and we both share the feeling that there’s something reifying about the biography and it can never do justice to the paths one has walked. It can never do justice to the path you have walked and the wisdom that you carry and the ancestors that you carry and the beings that you’ve interacted with that have changed your neural wiring to be this unique complex of being that you are.

So maybe we just start with the deschooling itself at a cultural level, given that you have these very wide ranging and intersecting interests from the soma to cultural analysis to working with horses to mythopoetic somatic movement to post-Taoism. From this complex of work and even beyond, what is your sense of the current prognosis of the dominant culture, the master narrative as you would say, and what do we need to unlearn as a culture and a society to get to any place that resembles desirable?

ZSD | Let’s go back to we made a decision about two minutes ago that took us about three seconds to not have all of the introductory type material. I think it actually mirrored unconsciously my decision in the workshop to not have that opening circle of identity. In fact, it’s really a more private version of the same thing. And I think the reason that I have such an impulse toward that is because identity is becoming pornographic, exaggerated. And I think the reason that identity is having that experience is because the strain toward identity is replacing belonging.

And then the question is how did that happen? What is this sense of belonging? By belonging I mean belonging to life, that there’s a tremendous nihilism underneath the culture of cheerfulness and achievement and identity and consumeristic agency to reinforce identity because you can have the economic agency for taste for acquiring certain things that reify identity.

I think that the question that we have to ask is: why is culture so interested in exaggerating the notion of identity and yet stripping people of uncomfortable or idiosyncratic or eccentric ideals outside of the circle of identities? Why is that going on? In other words, social media, (which I’ve never been on and I won’t be on because there’s no way for me to allow myself to be in a situation where my identity has to precede my experience), why is it that social media is an identity machine? Why does it have so much purchase? I think the reason for that is what I call the nemeses, which are the forces of this particular western European Americanized culture, this particular culture to defrock people, to extricate people, to remove people from any kind of sense of belonging that could not actually be stolen, violated, appropriated.

So we end up in an identity machine. I think we’re living in an identity machine, and it’s exhausting for everyone that I know. And you can think of identity as being the little food, the little scrap of food that the nemeses, these forces that are interested in us not belonging to existence – existential, ontological, religious, sensual, intellectual, emotional, spiritual, paranormal, esoteric, intuitive belonging. There are forces that are actively engaged in removing people from those consummations and those satisfactions. What they have given us instead are just a few things of which identity is the most insidious because identity feels like individuation, but it’s overrated and it’s over. It’s exploded in our time. And identities are a room of mirrors where they flow back and forth upon each other and everyone says, you are awesome, and oh my God, what a badass you are.

There’s all of this reflection back and forth about how everyone is building their identity, but they’re doing it in an absence of belonging. So, I would say that right now there’s a tremendous victory, a heart sickening, terrible victory of these nemeses to remove people almost categorically from the liquidity, the simplicity of it has lost its meaning.

And I’m not talking about a new age or even a very sophisticated Zen-like sense of being here and now, I don’t want to be mistaken for that. I mean something much more tumultuous and beautiful as being. And that’s what we’re going to hopefully get into when I talk about negative capability and post Taoism. But just an answer to that first introductory question, the reason that I don’t want to begin with you and I trading back and forth our identities is that it’s really not that important.

I don’t mean that in either a Christian sense of self-effacement or in any other kind of Eastern sense of not the way I mean that. What I mean is that the relationship to one’s soul and to other souls is so immediate that the resume that we allow ourselves to call an identity is actually not that interesting. It disappears. Identity brings us to the water of dissolution through Eros, and then we keep making a world-making self. And so, the reason that I didn’t start the workshop that we just had at this astonishing place where I am – Brave Earth in Costa Rica – the reason we didn’t have that identity making at the beginning is because I didn’t want to spend more than half the time deconstructing the resumes so that we could actually relate to one another. And I don’t want you and I to spend half of this conversation deconstructing the identities that we’ve resurrected for each other because they’re really lies.

AL | Indeed. Thank you. When you say the nemeses, what are you referring to?

ZSD | I will qualify this by saying that all of these nemeses have tremendously powerful and potentially positive aspects. So I don’t want anybody listening to this to think that I’m radically rejecting something without a round and deeply considered view of these things. There’s so many good and value forming and very positive aspects to most of them. But I want to talk about them in the way in which they’re used to affect this incapacity to belong to life. What I call the nemesis are capitalism, consumerism, which is of course a close sibling, and then, technology and organized religion. Everyone knows that technology saves lives, that communication is happening right now with what we’re doing via technology. And we could spend the whole time talking about what organized religion actually does in an astonishingly profound and enduring way for so many people.

We could even talk about certain ways in which consumerism in which the addiction to candy in the West relates to certain fair-trade farms that are now having a slightly better lifestyle because of consumerism. And we could talk about capitalism. I don’t know that one is hard for me to defend in any way. They’re all difficult. But what I want to talk about is the way in which the organization of religion encourages the shunting of the responsibility for the work of soul-making. And this is what people like Meister Eckhart were saying so many centuries ago, that if you depend on a scaffolding, you’ll never get anywhere. And so, I mean it in that sense. When I talk about technology, what I mean is that the separation of the erotic, of the vulnerable materiality of existence is passed through the plasticity of screens, the distancing that we are so accustomed to, the ability even to have the war that we’re going through right now in the Middle East, the ability to abide by its very complexity.

The variability that we have to be aware of it, the technology makes us aware of it, which is absolutely important. But the technology also makes us able to somehow abide by it. We are saturated in images of horror. We are saturated in the media that prevents us from the shocks. So, technology is a distancing; it is an anti-erotic force that we have become so accustomed to, to the point, for instance, that we are comforted when an artificial intelligence robot speaks to us with the resonance in their voice of competence.

So, technology encourages the lack of idiosyncrasy and human dynamic, and we’re actually comforted by the most inhuman voices. So, the central nervous system has been colonized to be calmed by the absence of humanity via technology. I mean, if you were to interview a lot of people and they were to have an AI customer service representative say, hello, how are you doing today? And then another voice that might have the vernacular of a particular group of people that might have a heavy accent from Latin America or from a beautiful idiosyncratic singsong of Black vernacular. It becomes less comforting, less secure from the artificial intelligence voice. And we live with that in terms of technology.

AL | There’s an impotence that comes from the mediation.

ZSD | Yes, that’s right. And what is that impotence? That impotence is in the language that I use in positing that impotence as encouragement to make people at home with a vast distance from their Jing. And the Jing is a term from traditional Chinese medicine that I have benefited from and separated myself from. The traditional Chinese medicine definition of Jing is the sheer sexual essence. The Taoists, the classical Taoists and the traditional Chinese medical culture, separate Jing and Chi and Shen. And so, when I say that these nemeses are invested in separating people from the Jing, I don’t mean their sexual energy because I define the Jing as the substance of the soul, by which I mean the particular potential of each individual and therefore the potential of the collective. As the consciousness of unified potentiates, there is a vested interest in removing people from the idea of destiny. Destiny meaning that one has the responsibility to fulfill their Jing, that things like instinct, desire, intuition, dream, longing, even ambition on the level of the soul’s cry out.

I was ambitious to learn horses, right? I was ambitious to understand how to read. Well, even on that level, we are asked to separate ourselves. So, when I say Jing throughout this conversation, I mean the vested interest in removing people from this natural instinct to be brave enough to become the shape of one’s soul. And we are living in a time in which radical people are in total agreement with that separation by virtue of being given these scraps of exaggerated identity. If you want to make someone feel really good about not having direct intimacy with their soul, give them a big dose of identity.

AL | I love this full circle thread back. So, when we ask what culture and society needs to unlearn, part of the practice is around identity itself, which is being formed by the structures, you call them the nemeses, essentially this is the operating system that we’re ensconced within. And then you move to this post-Taoist lens where instead of separating Chi, which is traditionally life force and Jing, which is the sexual force and Shen, which is the spiritual force, you’re essentially saying these are connected energies and it’s more than the physicality of energy that’s moving through the body. It’s the destiny of the soul. And when you don’t have that and you’re not connected to that, you cling to identity. The fabricated superficial identity that culture manufactures for us. We take on our role as citizen-subjects and our nation states and our desert myths and our religions, and these things become tantamount to a personality and an identity that is not connected to something more immense.

ZSD | The immensity, that’s a word that I use a lot. The soul is immense.

And experience is immense, but in order to communicate the soul to experience, there needs to be a language of the soul. And that language has been all but entirely eradicated through the culture of cheerfulness and achievement. So that’s how that’s affected. And one of the things that I’m trying to do in the philosophy of post-Taoism is dignify emotions and states of being that get a negative bad rap in terms of existence when they actually are what makes someone feel the immensity of what it is to belong. Emotions like grief, experiences like suffering. What is the purpose of anger? What is the purpose of suffering? What is the reason that we have such strong feelings? What about disorientation itself? I try to speak on a philosophical level about how these experiences are actually the way in which the soul shapes itself and makes it immune to the manipulations of a facile society.

So, in other words, when we grieve in this society, we are sick. We are considered basically disabled and sick, and the sooner that we can be restored into a productive mode, the healthier we are perceived to be. And that’s a tremendous sickness. If we understood that to grieve is the process by which we value something, we become commensurate with a loss, our personality becomes commensurate with a loss. And when our personalities become commensurate with a loss, then we cannot be redistributed back into a production society as if that’s our worth because we’ve been to a place where we understand why we live in the first place.

But if we think that grief is a disability that we have to recover from as quickly as possible in order to demonstrate some kind of sovereign, neoliberal, upright posture, performance prowess, then we’re never going to belong. And so, we’ve got a situation where basically the least amount of soul is the greatest amount of success and we’re in that loop.

And so, all of these questions, that’s why all of the questions about how to live, how to praise, how to overcome political and sociological dismaying circumstances, they’re all empty because there’s a great nihilism behind them that says when the protest is over, how many likes do I have? What’s my identity now? And so, these acts that used to be transgressions and transformative and used to cost the soul the value of being itself that is being taken away from us. Say that line one more time, that used to cost the soul. I can’t remember being themselves. We have souls and we’re here to make life commensurate with the immensity of those souls. And that has a cost. It has a cost; it has a cost in accepting that our sensitivity must at times make us damaged. Then there can be a recovery. But if we think we’re too immune to damage, there will be no recovery.

What is the cost of love? The cost of love is anything from deep betrayal and loneliness and abandonment to the unspeakable beauty of a consummation in all forms of love. But all along that vast immensity, there’s no place in actual love, in the actual exchange of the sacrifices and the loss of self and the finding of the self that goes on in great love. All of that is a cost that is not available to consumerism, to technology, to an organized spiritual religion. It’s not available to the capitalistic structure that says we are at our best when we are superficially healthy. In fact, health, one of the fulcrums by which this murder of soul is being affected is on the notion of health.

And I don’t want to talk, I don’t want to keep talking because I love your mind so much that I want to make sure that you speak.

AL | No, no. Say more please.

ZSD | Well, just that if you take away negative capability, by which I mean in this very short nutshell, by which I mean the power of certain disorienting emotions and certain perspectives of vertiginous helplessness. If you take away the power of those experiences, then you relegate health to the status of the least affected people. So, the healthy ones are the ones who don’t have the neck injuries and the disc deteriorations. You’ve lost your viability; you’ve lost your ability to concentrate through pain. You’ve lost your ability to concentrate on the job at hand through pain. And this is happening right now in one that I love. Through pain, you become aware of childhood infirmity, someone else’s experience.

You lose the specificity of your agency. And in this culture, that is the definition of a loss of health. Health is the one who is least sensitive because they can still perform. So, at the moment when a life to me is becoming healthy through the hesitations and the disorientation and the questioning that comes through even the least physical pain, they are considered healthy by the society. To me, they are beginning to belong. And that belonging and the acceptance of that belonging and all of its considerations – maybe I won’t travel on that airplane that long. Maybe I need to be here where I should be. Those are actually what makes the fabric of belonging and we’ve been completely deceived that prowess and performance and cheerfulness make meaning. And that is why we have modes of communication like social media where the design is to not inquire into the flora fauna of a person’s actual existence, and we celebrate achievement, and we push toward achievement.

So, we don’t have a language for the way in which belonging, and power is actually related to phases of discomfort and existential loss and infirmities. We celebrate superficial health as evolution. And that’s why the yoga journals can’t have a person whose face is beshadowed. You’re not going to see on the spiritual journals of today a face that might be navigating shades of depression. It’s impossible because you cannot sell the spirituality of transcendence if you traffic in infirmity. And that is a good tusk lie because the truth of belonging is always the transformation of infirmity into the eternity of belonging.

AL | I want to pause there for a second and just hold that the Occidental mind, the western socialized mind is going to say, ‘I don’t want infirmity’. And the cultivation of negative capability is not a way to transcend the pain. It’s not a way to do infirmity better. That’s not what you’re saying.

ZSD | Yes.

AL | I think this is critical, right? Because you’re not saying here’s another avenue to achieve that same state.

ZSD | Exactly.

AL | You’re saying that the state’s that come from not being okay from the wear and tear of empathy and what you would say sympathia is more soul transforming than what any of the veneer of the culture can offer. The health, the financial success, the house and the car, and all of the traditional trappings. And if someone asks you, how do you justify this claim, what do you say? And not that you want to persuade anyone, but to give them insight.

ZSD | I mean, that’s the cosmic joke. that what I’m saying is so universal that it’s embarrassing. And every single person on this earth, if they’re honest, would say that it is when they threw out their back that they understood how much they loved their wife. It is when they lost the job that they understood that they had been lying for 10 years in that career. It is when you were betrayed in love, that you had the opportunity to understand how precious your own soul is. And it would be, you go on and on with that. And there’s no one that escapes that, no one. And it’s a great joke that humanity has not evolved. I said in the workshop something like, the last president that could show his face as a totem of soul was Abraham Lincoln. And we now have leadership, we have faces and bodies and leadership that cannot express any infirmity even in their late seventies. Even in the late seventies.

And what I would say, you said the Occidental response to that would be ‘are you saying Zhenevere, that we all need to be perennially broken and sad and injured and depressed? Is that what this woman is saying?’ And that’s not at all what I’m saying. I’m saying that life, the ecology of life is dependent upon the bravest participation in the uncomfortable shades of being, in order to create an actual network of faith in life that can then do the marvelous things that make us belong, which is not to conventionally succeed.

Where there are those marvelous things, there is risk. So, I would say that’s the purpose, and there’s more to risk, to sacrifice. To feel, to be penetrable by someone else’s pain. Where is the fortitude? Where does it come from to risk, to feel someone else’s pain as if it were your own? Where does that come from? It comes from health, but it comes from health as I’m defining it, not from health as the distance from the potential of disability or a sacrifice of prowess.

And so, what we do is we hide, we cheat being, we go into our nuclear families which have been designed to hide the truth of the soul, and then we put the bandages on. If we’re lucky, we tell our intimates how our back hurts, we tell the people how we’ve just been diagnosed with diabetes. We say we have a heart condition and then we pump ourselves up and go back out and try and perform. And that divide, that divide creates loneliness. And in that loneliness, the society has this amazing answer: it’s called entertainment. Entertainment nulls the existential absurdity of that gulf. It’s an incredible gulf. Everyone goes home if they’re lucky and tells the truth about the soul where they tell it to themselves and then they go out and perform.

And what fills the disaster of that lie is the numbing of entertainment. And that is where the nemeses are victorious, if you cannot take your face and your body into the place where your genius called your vocation is working, if you cannot take that into that place, then you have to hide it. Then you have to hide it by cheerfulness and entertainment, and you have to root for the team and you’re going to need conventional substances, not ritualized substances, but conventional substances to lubricate that absurdity.

And that is why we have advertising, and why it works. That’s why we have a mania for sports. Whether these people make the kind of money that could run small countries for years, one of their salaries, that’s why we have this. The exaggeration of that is because the debt to the soul is that great.

That’s why we live in such a pornographic society in terms of sincerity. Sincerity we can imagine is the opposite of what we have made out of identity. The word identity today means the audacious willingness to push your personality’s resume into the fray of loneliness. And that’s how I would define identity today.

An identity that is bond and bounded to soul. What does that look like? How is it cultivated? I’m pointing to negative capability and potentially transitioning us to negative capability because what I’m learning from you is that there is a cultivation of this identity and soul can be recouped, but it requires practice and alertness. It is not going to happen within the confines of this culture. That is a categorical statement. And one of the reasons that I’m still imagining that teaching has a purpose, is that sentence is not going to happen.

And in this workshop that we just finished, it was amazing. I won’t say that person’s name, but I pointed out the way the eyes of that person became so wide and childlike to imagine that they’ve missed the opportunity to develop their power through trying too quickly to overcome depression or sorrow or grief or insecurity. I’ve gone through the traditional classical Taoist creation cycle, which identifies emotional qualities and some of them I’ve understood as really applicable to this, applicable to this situation. And some of them have had to pull out of my own imagination to try and make more useful patterns of the reinforcement of soul. So, for instance, if we look at wood, wood is an element in that cycle. And if we imagine the realm of wood instead of the element of wood, we imagine psyche in terms of wood, the ancient Chinese talked about wood very understandably and concurrently related with growth.

I am interested in what makes growth on the level of disorientation based on what I was just saying because my growth is not something that begins in its idea. I want to grow, so therefore I grow. It doesn’t begin there. And I’ve identified it as “awful inferiority” as a negative capability of the wood realm of existence, of the cosmology. I use the word awful in the old way as in full of awe. And I’ve grown in my life when I see and feel something in which I have an awful, a full of awe sense of inferiority. And because we don’t have a language for the beauty of that feeling, because any kind of inferiority must be annulled to represent this neoliberal high stature posture, an inviable posture. A person who cannot brook inferiority at all, we’re cut off from that notion. And I have depended on awful inferiority in order to become who I am.

And so that’s a negative capability. What is it? It means that when you see something beautiful or immense, you feel incapacitated. And in that incapacity instead of becoming either envious or in rejection, you become an erotic longing for self-sameness with that thing. So when Van Gogh is looking, Van Gogh is a master of negative capability. And if you read his letters, he’s always referring to these other painters and how astonishing what they do is and how it’s just almost unbelievable. And he writes for pages and pages about the way Monet uses color, the way Rembrandt can make soul in a way that he thinks it’s almost impossible to do. What’s happening in the alchemy of his ancient soul is that his daemon, his inner angel of authenticity, his daemon is being activated in order to cultivate risk. So awful inferiority is necessary to be inspired to take the inhale of risk.

And so that’s a negative capability. What is it? It means that when you see something beautiful or immense, you feel incapacitated. And in that incapacity instead of becoming either envious or in rejection, you become an erotic longing for self-sameness with that thing. So when Van Gogh is looking, Van Gogh is a master of negative capability. And if you read his letters, he’s always referring to these other painters and how astonishing what they do is and how it’s just almost unbelievable. And he writes for pages and pages about the way Monet uses color, the way Rembrandt can make soul in a way that he thinks it’s almost impossible to do. What’s happening in the alchemy of his ancient soul is that his daemon, his inner angel of authenticity, his daemon is being activated in order to cultivate risk. So awful inferiority is necessary to be inspired to take the inhale of risk.

Risk is always dependent upon an inhale, and awful inferiority causes the gasp of the inhale and says, you are so beautiful. I want a self-sameness with you. But if I’m told that I can’t experience inferiority and succeed and be successful or be healthy, I have to have a moment of non-conventional ill health. I have to think I can’t do that. I’m too short, I’m too emotional. I’m not focused enough. I have to go through these insecurities and then somebody very intelligent, well, let me finish that phrase. I have to go through these insecurities which we would try and null because we don’t have an education of the soul making potential of the power potential, of inferiority, of the feeling. We don’t see it as a phase. And that’s why I have laid in the lap of the Taoist cosmology because it’s a phase.

That’s what I love about the Taoist cosmologies is that we imbue phases and those phases are transformative. It’s just that the Taoist cosmology doesn’t traffic in the soul like this. And so, I’ve had to invent psycho-spiritual attributes to an elemental cosmology that are more directly useful to the process of making a soul in relationship, to becoming strong enough to withstand the nemeses in real-time so that a biography becomes the process of developing oneself in a very eternal way and one can become much more adept at not being interested in the seductions that are everywhere.

AL | The soul’s task in this context is very different from the soul’s task in a context, let’s say even a hundred years ago or 50 years ago. And so, there’s this interesting relationship between identity, the context of the nemeses in the state they’re in, whatever we want to call it, late-stage capitalism, the Anthropocene and the soul.

Part of what I would love to hear is, even though the notion of the soul for many will feel alien, what does being incarnated at this moment ask of us? I don’t know, perhaps can we say that the soul has chosen to incarnate in this moment in the face of all these struggles and all these difficulties and a culture that doesn’t even acknowledge its existence in order for transformation to happen beyond our linear rational understanding of what that could be?

ZSD | Well, is that too loaded? No, Al, no, no, no. Nothing you offer is too loaded. It’s just pleasure. Let’s not let this conversation end without talking about the war in the Middle East. A podcast is going to last a long time and disastrously new news will come and these atrocities will have to be logged into the memory as others come. But right now we have this situation with Palestine, Gaza, Israel, and if you speak as you do about now what’s being asked, if we look at negative capability and the relationship between pain and anger, or pain and revenge, as just as with an individual life, with a collective life, with a nation state, with nation states, with communities…If we imagine exactly the opposite, if we risk mysticism and imagine exactly the opposite to the Christian notion of the inherent sinfulness, and if we imagine that the altruism and the love that we feel tribally is actually meant to perforate into an ecological understanding, a sympathia en masse, which would characterize the true purpose of humanity as the evolution toward a mass sympathia, then if we look at negative capability in the way that I’m talking about it, we can imagine that atrocity is meant not to create an immediate mathematical response of revenge and violence and anger, but it is meant to create an ecological width of sympathy that is beyond reason. We are still living within the convenience of reason.

Eternity is available in the human being through compassion, through strange hermeneutics of sacrifice, understanding, pauses, hesitation, complications of consideration in this case historical consideration that would pause the lever of hatred and revenge. These are not available even to nation states because of a lack of the negative capabilities. So, if we trust the negative capabilities on an individual level, then we can begin to imagine how nation states would actually have things like hesitation, pause, lateral consideration, grief as an etymological soaking outward into sympathy, anger as a specific quality that then creates the transformation of that thing so that repetition becomes impossible because that specificity has been alchemized by virtue of its precision. These are the tangible ways that the little tiny thing that I’m talking about is actually geopolitical. And it is a great embarrassment that we have a situation like we do now where we have these toy soldiers and these lashings of unconsidered violence that move toward the dimensions of genocide without a single piece of dialogue that could consider soul. It is only action, reaction, violence, re-violence.

We should be so embarrassed as to feel a lean towards suicide as a species. We should consider that we do not deserve weather, that we do not deserve rain, that we do not deserve the sound of the tide, the feeling of animals roving around in the dark, that we do not deserve these things because to deserve them would be to ensoul human civilization in such a way that by now, by now, the conversation that would inevitably be happening now is what is the nature of catastrophe? What did it do in your soul? What did it make you think of?

We should be embarrassed that if we are responsible parents, we say things like, ‘don’t pick on Johnny. His parents are stressed at work economically and he’s unpredictable. Give him a wider berth, give him a wider berth. It’s school. Offer him a different kind of time. Half your sandwich. Don’t wield the guns and fight at recess.’ Those same adults that say things like that to their children are bombing each other without a single collateral thought of the making of the soul. And so negative capability. It is the truth that there are no longer political answers, there are only spiritual answers.

Nothing can be solved politically anymore. All there is is the individual soul and the collective soul working in tandem to understand the potential that negative capability has to transform one into the awareness of the ecological other. That’s all we have, and we have failed that. So absolutely what’s going to happen all of the time is conflict, hatred, disaster, repetition, and then reprieve from ourselves of entertainment on and on and on without end. And we’re seeing that played out right now. Walls will somehow be erected; hearths will be somehow attempted to be restored in the places of conventional might. Entertainment will come back into the culture and numb what happened. And in horrors where there is no possibility of resurrecting safety and comfort, they will be forgotten. And we have to cry so loudly. It’s not a cry against the atrocities, only it’s a cry for the loneliness of the soul. And the negative capabilities are the nutrition, the nourishment that the soul needs in order to expand consciousness in the way that I’m talking

AL | Do you believe we’re capable of that?

ZSD | I don’t know. I don’t know. And I’m pushing back having to pause the interview. I don’t know. I think that we must. Trauma is the subject. I say that trauma is the zeitgeist of our time. And I think the reason that trauma is the zeitgeist of our time is because trauma is the apotheosis of the absence of negative capability. Culturally, trauma is how the soul gets abandoned in its wound. And we would rather focus on trauma than on what makes trauma so inestimably inevitable. We would rather focus there because when we focus on trauma, we can begin to participate in the kind of exaggerations, the kind of dramas that the nemeses want us to participate in. So, we can have a savior and a victim which is familiar to the plots of the nemeses. And so, we glorify trauma in the face of trying to imagine its ideology. That is actually the most clever way to avoid negative capability.

So, when you ask me if there’s going to be a shift, it’s actually going to occur on the level of personal bravery. Very interestingly, Scott Peck said in his book of the eighties that ‘evil is the refusal to suffer.’ That’s a profound truth. And if we don’t develop the language of negative capability as the very structure of power, we will always choose to refuse suffering.

Why would you do anything else if you didn’t have elders, wiser older people, parents, teachers, instead of saying, ‘you are a mess, you are acting foolish, childish, wounded, sick, you disgrace me. Come back when your face is clean, come back when your posture is tall. Come back when you’re ready not to proffer your agency into the capitalist machine of productivity. Otherwise, I don’t want to see you.’

If we are creating a society like that, then we are creating trauma because trauma is the very correct hysteria in the absence of the development of the soul. And so, if there’s going to be any conversion of this pornography, it’s going to happen on the level of individual courage where people are somehow given a taste of negative capability as the foundation of actual power, which then translates into belonging. And I don’t see it happening. The reason I started to cry is because every system that we have, in particular the media, have proliferation of identity through successful achievements. I mean what is like, but an exclamation of a small successful achievement.

I like your face. I like the dance that you just put up. I like the song you made. I like. I’m not interested in the constituents of negative capability that made it possible. I like its sellable product. So, I don’t know. I don’t know. In this climate, which is headlong crafting us to be subsumed by artificial intelligence, that is the ultimate goal of the nemeses is to make us indistinguishable from artificial intelligence so that whatever powers can be will have no soul interruption, no groundedness, no beautiful transgression, no beautiful denials, no negativity, no ability to respond. That’s where we’re headed. And I think radicalism now can only be negative. There’s no place left for positive radicalism. There’s no positive anarchy. Any positive anarchy becomes its opposite in the instant of its semantic, it’s lost. Immediately it is appropriated. Immediately a protest is lost. The moment that everyone has their selfie sticks, then the protest is lost.

AL | What does negative anarchy or anarchism look like?

ZSD | Negative anarchism would be the willingness to absorb the absence of triumph. For instance, it is sickeningly exhilarating to drop bombs. It is heart rendering vertiginous to accept wound as unacceptable and to allow the wound to be shared, to be articulated, to have its time without having a recuperative response. So, a negative activism would have a different rhythm than we have now. We are caught in binaries because we don’t understand different peripheral rhythms. We have a capitalized sense of temporality. This thing that happened must be answered right now. We don’t have an awkward time. We don’t understand the value of feeling impotent in order to grow and deepen more eternal power. We can’t abide by infirmity, impotence, ambivalence, hesitation, confusion, disorientation. That is where values become interconnected with eternity. But because we have only reactivity, we have no chance. Negative anarchy would be an entirely different rhythm in which the soul would be centralized as the secret mystical power behind actual power. And that is possible, but so unlikely that I would be disingenuous to imagine it.

As possible. It is such a formidable thing. Everything is geared against it. Even our personal relationships are geared against it, right? We can’t stay in those places. We want to move on to what we call health. There needs to be a radical inversion. So, a negative anarchy would be an anarchy that must feel impotent for a small time while it develops its collateral constituency, it’s collateral values. If it just rebounds back, force meets force, atrocity meets protest. I’m not saying there’s no place for protests, but in the inner workings of protest, it is the alchemy that’s lacking. Otherwise, we are simply infantile. And that’s what I see.

AL | Beautiful. I think this is a perfect pregnant pause. This will be continued. We are in the middle.

ZSD | But can I say one more thing that I don’t want you to cut when this goes out? I miss your mind and I know that I’m the one being interviewed, but you and I have spent many, many days in discourse and in this particular moment I know that I’m obliged to give something of my thought and my caress, but I need to have another venue where we can imitate more the way we’ve been talking. And I do feel a sense of responsibility not to shirk the ideas that you’ve asked me, but I don’t want you to cut what I’m saying now because I want everyone to know that the Eros between our minds and our hearts has enabled me to be here in the first place. And that should be intense and alive dialogue.

AL | Part of the practice of Deschooling Dialogues is to share the insights and the practices of people like you who have shaped my soul in your ability to be able to be outside the culture enough to see that this is happening. And when I feel into this kind of arc, this mimetic arc that was created in our conversation, now, I don’t feel the need to insert my version of ‘identity through idea’ because there’s something to be said.

We’ve gone from what do we need to unlearn, which is identity itself. Currently our identity is linked to the superficiality of the nemeses, of our role as consumers. Our role is in some socioeconomic hierarchy. Our role as our identification with nation, state and religion. These are how we are finding belonging. How many people have reached out within the Jewish community to people I know in the Jewish community and have said, what are you doing for your community?

Rather than looking at truth, justice, historicity, etc. what we’re actually just looking for is these shallow understandings of identity that make us feel safe temporarily. And then keep us locked into the process of cause and effect. And when I hear you speak, what’s being activated for me is what you would call the daemon, the emissary of the soul that is saying to me, this is truth. And even though there’s this kind of communalistic, anarchist part of me that wants to believe that this is not an individual game, when you say things like, there’s great personal bravery that’s going to be required. I want to move to, there’s collective bravery that’s required. But there is no collective in absence of individual choice and will and agency. And unless we are willing to go to the depth of the soul, the interface with that daemon in whatever way is required. Silence, meditation, psychedelics, horses, equine therapy, whatever your practices to be able to access this interface with the daemon that is always there, that always exists.

But our distraction via entertainment, consumption, technology, etc. prevents us from accessing this. But it is possible. And when I hear your, in some ways your daemon speaking, what I’m compelled to realize and understand is that we must be willing to go to these sites of the wound, the trauma itself, and not try to pathologize it, not try to amputate the fact that trauma will happen, that illness will happen – this is not something to be cauterized – the site of the trauma is the moment of expansion into the wound, the moment of expansion into the goodness, the moment of expansion into the daemon’s ability to speak. Then all is lost. I also don’t know if it’s possible, but I think it’s critical that your contribution in this way is laid out without interference. Maybe summary but not interference. And there will be other venues for that.

ZSD | Well, I am only willing to say goodbye on this podcast if I say, you talked about your soul being in relationship to some of these ideas. My soul has been in relationship to some of your ideas. And that’s the only way that I feel truthful in saying goodbye to the listener in this conversation.

AL | Thank you for spending the time. It’s been an honor.

Deschooling Dialogues | Alnoor Ladha with Tiokasin Ghosthorse

DESCHOOLING DIALOGUES

Episode 4 – Alnoor Ladha with Tiokasin Ghosthorse

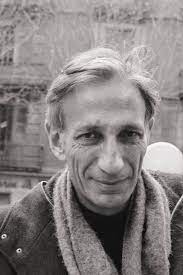

Alnoor Ladha | (LA) Welcome to the Deschooling Dialogues. This podcast is a co-creation of Culture Hack Labs and Kosmos Journal. Culture Hack Labs is a not-for-profit consultancy that supports organizations, social movements and activists to create cultural intervention for systems change. You can learn more@culturehack.io. Post-production is made possible by dedicated supporters of the Kosmos Journal mission, transformation in harmony with all of life. You can find out more@kosmosjournal.org. I’m your host, Alnoor Ladha. In this episode, I meet with Tiokasin Ghosthorse. Tiokasin is a Lakota elder. He is the founder and host of First Voices Radio that has been running for 31 years, the first Native-only radio show in Turtle Island. He’s also the founder of the Akantu Institute. He’s a dear mentor, older brother, friend, ally, teacher and elder. I’m excited to have him here on this episode of Deschooling Dialogues.

AL | Welcome Tiokasin.

Tiokasin Ghosthorse (TG) | Thank you so much for asking me.

AL | We’re meeting here in Kingston in upstate New York. Tiokasin does not live too far away. And I wanted to start with just a general introduction, not the traditional biography necessarily, because I know that would make him uncomfortable, but to ask about the inquiries you’ve been walking with and how you find yourself here in the historical civilizational crossroads we find ourselves in.

TG | Well, Alnoor, thank you for that. And thank you for this honor to be on the Deschooling Dialogues. And I think about this: how do we give praise or credit to that language that controls us? So we say…well, the moon, you were meant to be here like the moon, the sun, and the stars, right? So that’s a one-way street. But from where I think, it’s that the moon, the sun and the stars meant for me to be here. You see? And it changes everything. And I think that’s part of the deschooling, it’s how we perceive this binary language. It’s a destiny, even fate. We have no choice when chance is totally organized.

And so we work out of that spirit of being where we are, being present. I cannot be in the future and in the past at the same time, yet I can be. And that’s where we get the word Akantu: an Earth being in the ancient future now. As far as we know, Lakota is a 200,000 year old dialogue with Earth and where our thoughts come from – the listening underneath from the Earth. And it’s where our thoughts come from because we’re made up of that same composition.

AL | (03:42) Part of the inquiry of Deschooling Dialogues is an acknowledgement of this current moment that we’re in. I know the Hopi would call this the Time of the Sixth Sun or the Iroquois, the Prophecy of the Seventh Fire. And the Vedic tradition would say, this is the Kali Yuga, the Dark Ages. The Alchemical tradition would say, we’re in the underworld now. What do we need to understand about this current context in time? And what habits, practices, behaviors, cultural norms do we need to unlearn?

TG | Well, that’s a good question. There is no beginning and there will be no end to this, to put ourselves in context of being here in a spatial atmosphere, so to speak, not a temporal one. We’re not in rhythm with the Earth anymore. So our languages are not in rhythm with the Earth. We come up with ‘climate change’ and to some people that was caused by racism, it was caused by all these ‘isms’ that civilization came up with.

TG | Well, that’s a good question. There is no beginning and there will be no end to this, to put ourselves in context of being here in a spatial atmosphere, so to speak, not a temporal one. We’re not in rhythm with the Earth anymore. So our languages are not in rhythm with the Earth. We come up with ‘climate change’ and to some people that was caused by racism, it was caused by all these ‘isms’ that civilization came up with.

But when you bring that climate change to Native peoples, we’re going, what is that? It only speaks of being out of rhythm and understanding. We’re still expecting to adapt Earth to our needs, and there’s no contemplation about how much we take from Earth? Are we extracting from the Earth or even learning to respect it in ceremony?

So we revert to ritual and we cannot practice rituals. We have to live ceremony. And so, in this way, ceremony is constantly in the language. I’d say maybe three quarters of Lakota, Old Lakota is ceremonial creation within almost every word.

And when you get to that dialoguing with Earth, you understand that relation, the relational value, of these languages, how we learn. And I like the fact that you’re Sufi because you would understand this: that our values, which I can’t name all numerically right now, but those values we learn in silence. We can’t instruct them, we can’t point at them, but we understand the energy of it and this is how we keep who we are because we know what we’ve learned.

Western society is only a coat or the ‘colonial coma’ as our friend Vanessa [Andreotti] would say. And so it’s up to us to look at this colonial disposition that we all have. We go to the clothing store, we put on the errors of, ‘I have a PhD, I have this and this and this,’ and it works in that world, but does it work with the natural world? Where is the natural being these days?

So when I think about unlearning, it’s easier for me because I come from that base, not something that came on the ships or where I was forced to 2000 years ago, 3000 years ago when all the war happened against the Earth, to begin there by separating humans from the Earth. And so we continue to speak that language. And I think part of that is learning that history, as I have to understand what went on with them, that they had to jump on a ship and bring the pain without understanding the pain.

AL | (07:35) And so partly what you’re saying is, in order to deschool and unlearn, we first actually have to understand the impoverishment of the time and the moment we’re in, but also who your people are, what culture are they coming from? When you say the people who came off the ships, you’re talking about what Steven Jenkinson would call the spiritual orphans of the West. Those who came from Western Europe as part of the conquistador, colonial imperialist project, most of whom were not that themselves, but were the direct frontline troops of the English or the French or the Spanish or what have you. They were the kind of undergrowth, the so-called citizenry pushed to repopulate the badly named New World.

TG | It’s like looking west, and maybe for them it’s the right direction to the promised land, but the path they took was the wrong one.

And so you need to back up on that path. And you can picture this, you can picture this. It’s beyond metaphor, but if you understand the energy of this language that I’m speaking, that we are speaking now, it’s wasteful. The language looks at almost everything as having a waste, a conflict and antagonism at war with itself. Doubt, self-doubt, needs, how do you say, self-esteem therapy.

And so from that viewpoint, we saw the people needing that self-aggrandizement as the language comes from ‘I, me, my mine’ and ours that came over. We didn’t understand that, but we could see it in more of a whole. So we stepped back and watched it happen, and we understood that these people were spiritually starving because they brought religion, science and authoritative stances and everything that they could to come and conquer. Well, now it’s reversing itself. So when I talked about this, how do you say this, immunity.

AL | The auto-immune phase of the Anthropocene.

TG | This autoimmunity, this language, it’s eating itself. And this comes true with Sitting Bull. Now I’m going to repeat what I heard when I was very young, as best as I can. What happened is Sitting Bull saw this thing that he couldn’t figure out what it was…very many little white packages eating the land, and he couldn’t understand it.

And it turned out to be covered wagons eating the land. And it ran out of land to eat. And so when it turned on itself, which its doing now, and I can say the date that I know in my lifetime is 1992. 500 years after this thing, this white package. What eats itself are parasites. What eats itself that we could understand then was maggots. So this attitude, these ideas, this language is eating itself. That’s what I mean by autoimmune language.

AL | (11:40) And so maybe as we’re talking about the kind of unlearning aspect, you could give us a contrast with, for example, Old Lakota. From what I’ve learned from you, Old Lakota is a language based on verbs, on action and is therefore inherently animistic and alive versus the kind of dead, inert language of objectification and nouns and the thing-ification that is in English, in addition to what you said, it is a binary, oppositional kind of reductionist language. But there’s something core to Old Lakota that you’ve spoken about before, which is that the learning and the unlearning and the wisdom is in the very language itself as a living entity.

AL | (11:40) And so maybe as we’re talking about the kind of unlearning aspect, you could give us a contrast with, for example, Old Lakota. From what I’ve learned from you, Old Lakota is a language based on verbs, on action and is therefore inherently animistic and alive versus the kind of dead, inert language of objectification and nouns and the thing-ification that is in English, in addition to what you said, it is a binary, oppositional kind of reductionist language. But there’s something core to Old Lakota that you’ve spoken about before, which is that the learning and the unlearning and the wisdom is in the very language itself as a living entity.

TG | It’s like speaking a commonsense language that misses. When I talked earlier about cultural diversity, well, the reason why we are more or less resilient is that we know where the power, the oracle is. And to walk with that with, as you would say, dignity, but to walk with the Earth beneath your feet, stars above, and these pictures, these ideas that this energy is to understand what we are saying.

So when we speak this language is so that you understand the energy, you describe the energy, then you understand the motion of the energy, and that’s all you need! And that comes without conceptual thinking because it’s the feeling that’s there, that’s present. And when you’re present with the feeling you can see everything. One of the ancestors said, the center of the universe is everywhere. So you have quantum physics within the language that helps you go outside of the box of conception.

The box that I describe as ‘the beginning and the ending’, the superior, inferior, the cause and effect, those are very right-angled thinking or thought processes. And so if you have verbs, it’s always a continuum. And in order to have to be in the continuum, you need the verbs to see where you are in the present always. And to understand the energies are beyond just material, the world realm and the dimensions that we see, you really can see them.

You can listen to the plants, you can hear their music, everything, but you have to be in the language. We just can’t say, oh, I hear plants. And just kind of like tongue-in-cheek philosophies you really can, we’ve known this. We know that trees communicate, we’ve known that before books were written. We’ve known about the mushrooms; we’ve known about this. But that’s the slower learning process. So it’ll be easier for me to unlearn, take the coats off because the process of learning is slow. It’s not like you say quick, you go to class, you got it, you come back for another and then you get your degree saying, you know something. But that’s only survival in this society.

So I think part of that is using this language that we’re speaking less and understanding the energy that we’re feeling that has no expression in this language.

AL | (15:25) Beautiful. Thank you. And another aspect then around deschooling is maybe private property and all of our conceptions of ownership, which are also related to language. ‘Mine me’, is the egocentric language that is sort of core to the Eurocentric approach. Maybe you could say something about the dissolution of these abstract ideas that have so much material influence. Our laws are just essentially built around the protection of private property for a gentry class of historically white Christian males.

TG | Wow. Well, from what I understand of this history of the West, how ownership got here is that we have it now. We have it in our colonized view as native people because we have to survive in it. So everything is moving in that direction. And that’s a loss to cultures of Earth.

Civilizations, you can have the one that I spoke about ‘spiritual civilization’. I don’t know if there’s something like that. There’s religious civilization, but spirituality to me always has culture. The culture of spirit, and spirit defines that culture, and therefore these words are not mine. It’s the message behind that.

Silence again is the biggest decoder, the master of unlearning because you get to feel what you’re thinking, not conceive what you think you’re thinking, if that makes sense. So this is why ceremony is part of that unlearning, as you know. It’s unlearning, seeing, perceiving, not even questioning, because that question deserves an answer, so to speak. It’s that accepting without allowing that answer to overwhelm you like heaven and hell, it’s very dualistic thinking. So it’s silence that’s the biggest healer. Silence is something that is all around. You swim in it every day like intuition. Intuition is the language of silence.

Silence again is the biggest decoder, the master of unlearning because you get to feel what you’re thinking, not conceive what you think you’re thinking, if that makes sense. So this is why ceremony is part of that unlearning, as you know. It’s unlearning, seeing, perceiving, not even questioning, because that question deserves an answer, so to speak. It’s that accepting without allowing that answer to overwhelm you like heaven and hell, it’s very dualistic thinking. So it’s silence that’s the biggest healer. Silence is something that is all around. You swim in it every day like intuition. Intuition is the language of silence.

AL | (17:54) Say a little more about your conception of intuition, because I think this is also of course core to the notion deschooling, right? We’ve formalized our abstract thinking and then we’ve married that with vocation where the entire point of education is to get a job, to be a cog in the capitalist machinery. And so what is the role of intuition as part of our, let’s say, initiation into at least attempts at a wisdom culture.

TG | ‘Common sense culture’, I would say. So intuition, at least to me, my thought process is it’s a being. How are we treating intuition by saying it’s a hunch, it’s a guess. It’s a gut feeling. It’s very disrespectful when we look at it that way or we roll the dice. Intuition already knows where it needs to be. It doesn’t cost anything, right? It’s totally free. And when you’re free, all dimensions are available. And so where’s the language to describe that free? The being-intuition.

And in comes the human being that no longer knows how to be a human being but has become a human doing. That they do so many things that they forget the essence of the silence that they were born from, into, and will go out of this dimension in. It’s to understand that peace with Earth is peace honored and it’s simple. That’s what I could come up with. Peace with Earth is peace honored.

Now to have an answer for you. The spirits have to tell you this. It does not mean I’m a shaman or spiritual guru or anything like that, a medicine person. I’m just a regular being with common sense. And when you’re in that place, when you see the light beyond what you can describe with the words of this language, even my language is that we are out of rhythm with nature so much that we have to call it ‘nature’. Nature, or you say Gaia, I say Mother Earth, which is not really what Maka Ina means. In fact, it’s beyond that description of this language. So we have a lot of work to do to unlearn, to deschool, to un-Westernize. To take Maka Ina again, to unlearn, to wake up from the coma.

AL | (20:42) Maybe this is the last question as I want to honor your time. A westerner saying, okay, well I understand what you’re saying around silence, around intuition, around language, but I need to put food on the table and put my kids to school and play my role in the machinery of capitalist modernity. What would you say to that person?

TG | I would say, how much do you want to participate in giving yourself away?

There is no word for sacrifice [in Lakota] – it is that which gives itself to you – that is sacrifice. We are taught that, again, we don’t lead; we don’t follow, we walk with – which is sacrificing to us. And so we have to always treat that in a ceremony. Everything is ceremony to us. So as a language, and when I think about, yeah, I have to drive a car to get here, I have to have food. And we are taught to ask in this society – basically a beggar’s language, a language of scarcity.

But on the other end is, well, you must speak a language of abundance, that’s not “it”. That’s not the opposite of scarcity. So, it is just what it is. What do you need today? Because the future will always, if you understand today, the future will always be available as well as the knowledge of the past. And I think that’s where we have to decode our own thinking and get away from the ego as you understand- the identity that we’re supposed to have within the survivor language. This is a survivor’s language that we’re speaking. Whereas you can’t speak this way in Old Lakota, you can’t speak a survivor’s language based on fear. And if you consider fear a being, then you also understand how this society understands it. Dualistically.

AL | (22:58) There’s a line that has come to me a couple of times in meditation and ceremony, which is, “trust is the ultimate suicide pact with the universe. You have to be able to stand at the edge of consciousness and be willing to fall and know that you will be caught.”

TG | I love that.

AL | And even the relationship with scarcity and abundance and money, it’s like part of a spiritual practice that I know I will be provided for if I am in resonance with the desires of Mother Earth, Pachamama, the Gaian whole, whatever you want to call it. But that requires a belief in something bigger than you.

Yet institutional religions of the West, the corporate capitalist structures, the political leaders, the media, they’ve hollowed out that relationship. They’ve said, trust us, right? Academia, science, we know the answer to everything. We’ll get the grand unifying theory of everything. Here’s why you’re doing what you’re doing. Here’s where we’re going. Here’s the capital T truth on the human experience in all the ways historically cognitively, neuro-scientifically, physically, metaphysically. And so this monopoly has mediated our relationship with something bigger than us to trust and to be in service to. And that gap requires some bridging. And we’re like these spiritual orphans on one side of this vast chasm with no bridge. And maybe you could leave us with? What does that bridge look like? Is there even a bridge? Is there a way to build that bridge? Is there something we can do in our bodies to start even attempting to conceive of the bridge?

TG | There is no bridge.

If you’re in it and you’re understanding your place, that like you were meant to be here, that sounds so cliche, but Wana, Wana means now. And like we say, Taku Ashka, which means the spirit behind the spirit, behind the spirit, behind the spirit. It’s like dimensional effects that we have. Where does your energy go when you speak? It just doesn’t stay right here. It goes out. Technically this broadcast, spiritually, energetically. It always moves and it always, you identify that if you understand that the continuum, not of time, but the continuum of emotion and energy, that’s where it comes from. So, if we understand that I am not the message, but the message that I carry is bigger. And that’s why I think First Voices Radio is what it is because it’s always been about the message that it goes. And somehow, I don’t see how it kept going with no funding, blah, blah, blah.

AL | (26:03) And you’re not planning for that?

TG | No, I’m not planning for it. I just want to be here because that’s the message, to be here.

AL | And I love that you’re just so direct about it. There is no bridge, but there is an awareness of consequence. And if we are aware of the consequences in the present moment and anchored in the present moment and in place, then we can actually deepen our practice of trust.

TG | Yes, because the Earth trusts you to give to you air, water, food, comfort, all of that. And you see that that overwhelms all the discomforts. And we need to be between those quote ‘dimensions’ or worlds to understand the mystery that it already understands us.

The trees acknowledge us when we walk in the forest. We don’t go to nature. Nature is in us. So we never separate it. We don’t have to build bridges; we don’t have to connect. We’re in relationship, we’re in dialogue. We’re in conversation all the time with everything that we know, atomically down to the neutron is, that everything is alive.

We’ve known that way before Western science came here. And to lose that means that we’re going to have to give up our relationship with nature and the quick fixes that are coming. that are here and now have to be proved, proven by science. And we just kind of sit back because we know that we have the time, so to speak. So patience is one of the virtues that you learn in silence. It’s not taught; you learn it.

AL | Beautiful. I think that’s a great place to end. Thank you so much for your time, for your eldership, for the way you walk in the world and all that you do.

TG | Honored. Honored, always. Alnoor, thank you so much for this. It’s good to be here.

Deschooling Dialogues | Alnoor Ladha with Sophie Strand

DESCHOOLING DIALOGUES

Episode 3 – Alnoor Ladha with Sophie Strand

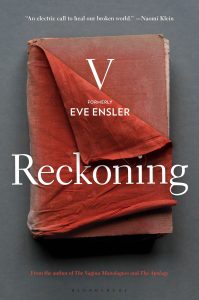

In this episode of Deschooling Dialogues, host Alnoor Ladha talks with Sophie Strand. She is a writer based in the Hudson Valley who focuses on the intersection of spirituality, storytelling, and ecology. But it would probably be more authentic to call her “a neo-troubadour animist with a propensity to spin yarns that inevitably turn into love stories.”

Her first book of essays, The Flowering Wand: Lunar Kings, Lichenized Lovers, Transpecies Magicians, and Rhizomatic Harpists Heal the Masculine is out now from Inner Traditions. Her eco-feminist historical fiction reimagining of the gospels The Madonna Secret will also be published soon. Her books of poetry include Love Song to a Blue God (Oread Press) and Those Other Flowers to Come (Dancing Girl Press) and The Approach (The Swan). Follow her on Facebook or on Instagram @cosmogyny.

AL | Welcome to the Deschooling Dialogues. This podcast is a co-creation between Culture Hack Labs and Kosmos Journal. Culture Hack Labs is a not-for-profit advisory that supports organizations, social movements and activists to create cultural interventions for systems change. You can find out more at culturehack.io.

Post-production is made possible by the dedicated supporters of Kosmos Journal, focused on transformation in harmony with all Life. You can find out more at kosmosjournal.org. And thank you to Radio Kingston for the use of this space today. I’m your host, Alnoor Ladha.

I’m here with Sophie Strand, who’s a dear friend, sibling, an inspiration when it comes to weaving words and worlds. She is a writer, a compost heap, a troubadour, an animist, and she’s the author of the Flowering Wand, which is out now, and Madonna’s Secret, which is coming out this summer. Welcome to Deschooling Dialogues. Thank you for being with us and taking the time.

SS| Thank you so much for having me and for having my little dog who may vocalize during this.

AL | So let’s start with a little bit about the inquiries you’re holding now and a little bit about the journey.

SS | A little bit about the journey. I was raised in a swamp of Theravada Buddhist monks, rabbis, theologians, rescued possums, raccoons, mountains. My parents write about the history of religion and they also write about ecology. So, I definitely have a root system in these things and was produced by dinner table conversations that range from eco-anarchism to the history of Christianity.

SS | A little bit about the journey. I was raised in a swamp of Theravada Buddhist monks, rabbis, theologians, rescued possums, raccoons, mountains. My parents write about the history of religion and they also write about ecology. So, I definitely have a root system in these things and was produced by dinner table conversations that range from eco-anarchism to the history of Christianity.

These days, I’m thinking a lot about healing paradigms and how they’re helpful and how they also constrict us and foreclose certain possibilities for wellness. And I am looking at my own story with chronic illness and with trauma under a different lens, under a more interspecies lens, trying to problematize the ways in which I have focused on the human when it comes to healing instead of my wider connectivity. What are you thinking about right now? I know you just finished a book on philanthropy, composting philanthropy.

AL | Kind of against my will. Yes. I think a lot about post capitalism, not in a temporal sense of what comes after this existing system, but more about what are the enabling conditions to create embodied cultures worth living. And I see a lot of parallel between our work in the sense that you often go to ecology for your inspiration. We were talking about pigweed the other day, and you gave me the metaphor of pigweed, and I thought, wow, that’s a post-capitalist being, the pigweed. Maybe you can say a little bit about it.

SS | So a little context, my grandmother was an English rose gardener, and she didn’t know better, and she used glyphosate in her rose garden, and she died of complications from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which is now shown to be directly caused by glyphosate, and posthumously she was included in the class action suit against them, and I think a lot about it. She was the person who I felt closest to. She lived with us as she died. I loved her quite a bit. She was a gardener and a lover of plants, completely pagan without knowing that that’s what she was. And I think about how we are all threaded through with microplastics. We’re all drinking water with blood pressure stabilizers and pesticide in it and experiencing auto-immunity and cascading physical glitches that of course, the environment is also experiencing at a much higher degree.

And for me, I was thinking, I can’t purify myself. I can’t put myself into some machine that purifies my blood and fixes me. I need a good metaphor. And so, in medieval England, there were cults of saints and it seemed Christian, but really, they were syncretic with much earlier tutelary land deities. So certain plants, certain springs, certain valleys would have healing attributes, and they became conflated with Christian saints so that they could still exist within the oppressive paradigm of colonial Christianity. But they pointed to plants and animals and places that could heal you. So, you would pray to a certain saint for a toothache, for a fever, for heartache. And so, I’ve created my own cult of saints, but they’re all plants and animals and microbes, and they’re the plants and animals and microbes that are, as you said, post capitalist; ones that are not the master’s tools.

“The master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house” [Audre Lorde]. They’re always the dirtiest, most hated beings. And one of those is pigweed. And pigweed is a weed – it’s actually indigenous to America, but we treat it like an invasive species because it destroys our monocropping. It’ll get into a field. They have these deep tap roots that are impossible to get rid of without something called flame weeding where you burn down the entire field. And the best thing is they genetically outpace pesticides that they can outpace glyphosate in one generation.

AL | As their adaptive mechanism.

SS | And so they can metabolize the pesticide and learn how to get rid of it immediately. And so I started praying to pigweed just to teach me how to alchemize these poisons in my own body. So that’s one. But I like calling them post capitalism, like co-conspirators.

AL | They’re sort of apocalyptic, but also post capitalistic deities.

SS | Yeah. Do you have one right now? Can you think of one?

AL | The one that comes to mind, and you’ll probably know the Latin names better than me, is the particular fungi that infects the ant.

SS | Ophiocordyceps unilateralis.

AL | There you go. I knew you would. And why I think the metaphor is so interesting is that it doesn’t have a body in that sense. It can’t get to the top of the tree, but it can infuse the ant’s body and become a symbiont with the ant. And the research on it is really interesting because they don’t know if it’s affecting the neurology of the ant; if it’s happening at a strictly neurochemical level, like the ant is high. They haven’t figured out what the mechanism is; in which way is it doing this. And I think in some ways that the kind of post capitalist resistance is like what we have to ride the bodies of – in some ways, more mobile, more superior creatures and take root in logic like that.

SS | Yeah. I love that metaphor too. I often think of that ant when I think of art, which is ‘good art is never you’. It’s always using your body and hijacking you to do something that’s bigger than you. And that experience is usually terrifying. We do not know what that ant is experiencing, but I think Merlin Sheldrake says by the time the ant’s at the top of the plant, it’s a fungus in an ant costume, which I love. How can we become fungus in human costumes and trees in human costumes? How can we let ourselves be colonized by these beings?

AL | For me, this kind of line of thinking comes with the idea of purpose. I think a lot about how, in the living world, no species requires purpose or is contemplating their purpose or is navel gazing about its purpose. And the West is obsessed with it. From career counselors to the kind of Fordist procession that moves us towards some kind of vocational job. When you’ve come out of high school and you get these seven bad options of architect, lawyer or doctor or whatever, before we even know what we are orienting towards. A plant understands photosynthesis. It has its teleology if you will, intact. And we’re so rudderless, especially in a culture that tells us a kind of materialist reductionist fallacy of acquisition is going to somehow save us. And the only thing we need to do is whatever’s required to get us into a relatively hierarchical position to acquire more, consume more, validate more, et cetera.

SS | I was thinking about accumulation. We want to accumulate as much as possible, put as much into our bodies. And by extension, we’re making as much land into places to grow our food, our monocrops, or our cows and our chickens, which are an extension of our own bodies. But I often think of these spiders that always die when they reproduce, or they will jump into the mouths of these giant female spiders and die.

There were these rare spiders in this zoo, and they were trying to get them to reproduce, and they were waiting and trying to make sure that the lady spider didn’t eat him before they mated. And she ate him and everyone despaired because they were the last of their kind. And then two weeks later, she was pregnant. He managed to, as he was dying, do the act. And for me, I was always thinking, we think that that’s a life wasted. We think we have to save life, but life doesn’t have a savings account. It spends everything at once always.

AL | And maybe there’s a transition between these two. I think I told you about my uncle before. I remember being about 17 years old, and the career counselor or whatever they called them back then, gave me all this propaganda for Canadian universities. I’m looking at this and my uncle walks in the room and he’s like, ‘what are you doing?’ And I said, well, I have to pick what university I want to go to. And then he just sort of laughed and he was like, ‘you’ve become so colonized.’ And then his line was, ‘your life is a consequence of your prayer.’

SS | Beautiful.

AL | ‘Your life is the consequence of your prayer.’ You don’t like your optionalities, you don’t like your choice set. Go to your altar, go do your Dhikr, which is Arabic mantra, refine your prayer, and then you can negotiate with Life again. And it just recalibrated the way I was approaching this limited choice set of what I could do and what my purpose was. There is no purpose. There’s only prayer, and you’re in dialogue with this animate world. There’s a pathway in death also because I think death-phobia is driving most of our motivations at a civilizational level. It’s obvious, when we look at healthcare for example, or end of life care, palliative care, and Elon Musk wanting to go to Mars and uploading our consciousness to the AI and all of that, but also at a daily kind of quotidian way, our purpose and death are so entwined.

SS | Well, I think it’s interesting. I was just thinking of this great line from my favorite Linda Hogan poem, which is “to enter life, be food”. I think maybe the most terrifying thing is to really realize what our purpose is, which is to be food, to ‘become food’, to make ourselves edible. How do we make ourselves edible? It’s not about being a doctor or doing anything of the sort. It’s about making sure that at the end of our lives we could be eaten. And that’s very terrifying. That’s so closely wedded to death.

SS | Well, I think it’s interesting. I was just thinking of this great line from my favorite Linda Hogan poem, which is “to enter life, be food”. I think maybe the most terrifying thing is to really realize what our purpose is, which is to be food, to ‘become food’, to make ourselves edible. How do we make ourselves edible? It’s not about being a doctor or doing anything of the sort. It’s about making sure that at the end of our lives we could be eaten. And that’s very terrifying. That’s so closely wedded to death.

I often think that our fear of death is also closely linked to our weird relationships to food webs. That food webs are created by waste, by delicately plugging your waste into another being’s appetite. That’s how the nitrogen and the salmon make it all the way into the rivers, then into the bear’s bodies from out in the ocean, that the ocean is tied in deep, deep miles into the land by these salmon and by their waste decaying and being eaten by bears. And then the bears are pooping on the shore of these rivers. We don’t know how to make our waste edible anymore. We don’t know how to make our death edible. So I sometimes think that my purpose in life is just really simple. It’s very material. How do I make sure that at the end of my life I can be eaten?