The Practice of Lucid Dreaming

The Practice of Lucid Dreaming

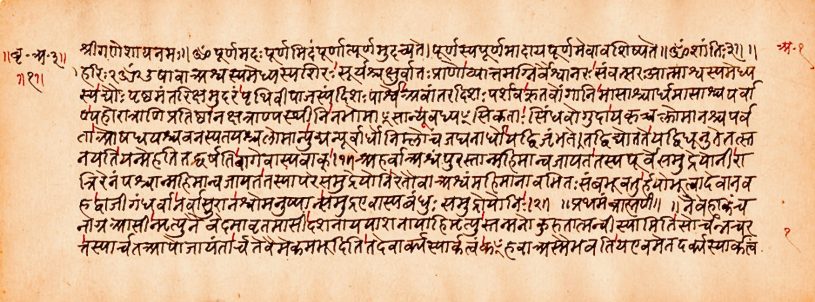

When one goes to sleep, he takes along the material of this all-containing world, himself tears it apart, himself builds it up, and dreams by his own brightness, by his own light. Then this person becomes self-illuminated. There are no chariots, spans, roads. But he projects from himself chariots, spans, roads. There are no blisses there, no pleasures, no delights. But he projects from himself blisses, pleasures, delights. . . . For he is a creator.

– Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 6th Century BCE.

The earliest religious texts among the people of the Indus River Valley, known as the Vedas, included a variety of practical measures to please the gods, including prayers, ethical precepts, and instructions for rituals and sacrifices. At some point after the Vedas, another kind of religious text emerged, the Upanishads, written by unknown figures over many centuries. Turning the focus of religious practice inward, the Upanishads presents a mystical philosophy of the self.

The spiritual insights in these texts can be profound, and, in the realm of dream research, highly relevant to our present-day concerns. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad presents a model of dream formation that seems to rely on nothing other than the creative power of the dreamer’s own mind. No gods or demons are involved, no journeys of the soul, no mingling with spirit beings. All that appears in dreaming, according to this text, is projected from the dreamer, drawing on the energy of “his own brightness, his own light.” This might sound like a surprisingly modern theory, close to what we dream researchers today call the neurocognitive approach. And yet the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad places dreams within a bigger framework of the spiritual evolution of consciousness. The text describes four basic states of being: waking, dreaming, dreamless sleep, and turiya, which is a transcendent state of divine immersion and infinite consciousness. In this setting, the exploration of dreaming becomes a valuable source of spiritual growth.

This realization—that the inner light of your unconscious generates the worlds of your dreams—can become a stepping stone toward the higher realization that the divine light creates the world of your waking reality.

Just as God creates the universe, you create your dreams. To see more of that creative power in yourself is to see more of it in the world too.

In the contemporary study of dreams, the biggest of big fish for many researchers is consciousness—specifically the kind of consciousness that appears in lucid dreams. Maybe you have experienced dreams yourself, in which you were aware of being within a dream. Perhaps you have never had a dream like that, and you are curious why some people get so excited about the idea. For as long as I have been in the field, researchers have been arguing about the nature and significance of lucid dreaming.

We in the modern West did not “discover” lucid dreaming. As indicated by the opening quote from the Upanishads, people throughout history have been familiar with variations in self-awareness within dreaming. In later Buddhist traditions in India, China, and elsewhere, efforts were made to extend classic practices of meditation into sleep, with the resulting insight into the self-created nature of reality. Here is a passage from The Life of Milarepa, a sacred autobiography by a famous Tibetan Buddhist sage from the eleventh century CE:

During the day I had the sensation of being able to change my body at will and of levitating through space and performing miracles. At night in my dreams I could freely and without obstacles explore the entire universe from one end to the other. And, transforming myself into hundreds of different material and spiritual bodies, I visited all the Buddha realms and listened to the teachings there. Also, I could preach the Dharma to a multitude of beings. My body could be both in flames and spouting water. Having thus obtained inconceivably miraculous powers, I meditated joyfully and with heightened spirit.

Rubin Museum of Art | Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin

C2006.66.460 (HAR 921)

This sounds like a peak lucid dreaming experience. And yet, in the context of Milarepa’s life and spiritual development, it only marked a momentary stage in his further growth. Two points are crucial here: first, Milarepa’s incredible powers did not appear instantly but only after years of patient training and meditation practice. There is no fast and easy method for having these kinds of dreams. And second, Milarepa did not become attached to these powers, as if becoming a magician was the goal; rather, he let them fall by the wayside as he moved forward in his spiritual journey.

A similar insight comes in another classic work of Asian spirituality, The Inner Chapters by the Daoist sage Zhuang Zi in the third century CE. You may already be familiar with this text, in which Zhuang Zi shares an extremely vivid dream of being a butterfly, flying freely in the air. Then he suddenly wakes up and wonders if he’s a man who dreamed of being a butterfly or a butterfly who is now dreaming of being a man.

For Zhuang Zi and the Daoist tradition, his dream offers a memorably poetic expression of the higher truth of the transformation of all things. Within this lineage of spiritual wisdom and practice, gaining magical powers matters far less than learning to recognize the endless flow of consciousness as it shifts from one state to another.

Becoming a Lucid Dreamer

In developing dream recall, as with any other skill, progress is sometimes slow. Don’t be discouraged if you don’t succeed at first. Virtually everyone improves through practice. As soon as you recall your dreams at least once per night, you’re ready to try lucid dreaming.

Keeping a dream journal

Get a notebook or diary for writing down your dreams. The notebook should be attractive to you and exclusively dedicated for the purpose of recording dreams. Place it by your bedside to remind yourself of your intention to write down dreams. Record your dreams immediately after you awaken from them. You can either write out the entire dream upon awakening from it or take down brief notes to expand later.

Your dream journal is a tool, and you are the only person who is going to read it. Describe the way images and characters look and sound and smell, and don’t forget to describe the way you felt in the dream—emotional reactions are important clues in the dream world. Record anything unusual, the kinds of things that would never occur in waking life.

Dreamsigns: Doors to Lucidity

A strange little detail in your dream may help you to realize you are dreaming. I have named such characteristically dreamlike features “dreamsigns.” Almost every dream has dreamsigns, and it is likely that we all have our own personal ones.

Once you know how to look for them, dreamsigns can be like neon lights, flashing a message in the darkness: “This is a dream! This is a dream!” You can use your journal as a rich source of information on how your own dreams signal their dreamlike nature. By training yourself to recognize dreamsigns, you will enhance your ability to use this natural method of becoming lucid.

Autosuggestion Technique

Relax completely

While lying in bed, gently close your eyes and relax your head, neck, back, arms, and legs. Completely let go of all muscular and mental tension, and breathe slowly and restfully. Enjoy the feeling of relaxation and let go of your thoughts, worries, concerns, and plans. If you have just awakened from sleep, you are probably already sufficiently relaxed.

Tell yourself that you will have a lucid dream

While remaining deeply relaxed, suggest to yourself that you are going to have a lucid dream, either later the same night or on some other night in the near future. Avoid putting intentional effort into your suggestion. Instead, attempt to put yourself in the frame of mind of genuinely expecting that you will have a lucid dream tonight or sometime soon. Let yourself think expectantly about the lucid dream you are about to have. Look forward to it, but be willing to let it happen all in good time.

Excerpt from: Exploring The World Of Lucid Dreaming

A Step By Step Guide By Stephan Laberge

Internet Archive

Turiya is not that which is conscious of the inner (subjective) world,

nor that which is conscious of the outer (objective) world,

nor that which is conscious of both, nor that which is a mass of consciousness.

It is not simple consciousness nor is It unconsciousness.

It is unperceived, unrelated, incomprehensible, uninferable, unthinkable, and indescribable.

– Mandukya Upanishad

All composed things are like a dream, a phantom, a drop of dew, a flash of lightning.

That is how to meditate on them, That is how to observe them.

– The Diamond Sutra

Just as, O king, a dream is unreal, so is the universe. Who is it who constructs the universe? This is also unreal.

– The Questions of King Milinda (Milindapañha)

It is clear that all three major religious traditions of Asia—Hinduism, Buddhism, and Daoism—have been familiar for thousands of years with experiences of self-awareness in dreaming. More than that, all three of these traditions have developed practices aimed at cultivating these kinds of dream experiences and channeling their energies toward spiritual growth and enlightenment.

Much less attention to the conscious dimensions of dreaming appears in Western history. Although the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle mentions in passing the occurrence of self-awareness in dreaming, he gives no special attention to it. The rise of the Abrahamic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam put more emphasis on the content of dreams as messages of divine reassurance and prophetic warning. But they bracketed out the questions Zhuang Zi and other Asian mystics were asking about the form of dreaming as a state of consciousness.

Eventually, in modern Western society, it no longer became possible, as a matter of linguistic usage and common sense, even to speak about self-awareness in dreaming. Talking about being aware in a dream was like talking about the coolness of fire or the softness of a rock: you were making no sense. People could talk about lucid dreams in the context of occult and esoteric writings, but these reports were often meandering and impressionistic, making it easy for mainstream scientists to dismiss them out of hand.

Making broad generalizations about something as complex and multifaceted as human religiosity is difficult. Yet the historical evidence suggests a real difference of attitude toward lucid dreaming between the Asian religious traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Daoism, on the one hand, and the Abrahamic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, on the other.

The former group, by and large, acknowledges the varieties of consciousness in dreams and sees this as a spiritual opportunity. The latter group, by and large, ignores consciousness in dreaming and regards it as spiritually irrelevant. Most Indigenous cultures, especially those with shamanic practices, would seem to side with the Asian religious traditions on this issue.

Neither perspective is ‘right or wrong’. If nothing else, this brief history suggests that the current excitement about lucid dreaming in the modern West might represent a kind of cultural rebound effect. Perhaps many of us are experiencing a new surge of interest in lucid dreaming because our culture has paid such minimal attention to this aspect of our dreaming selves for centuries.

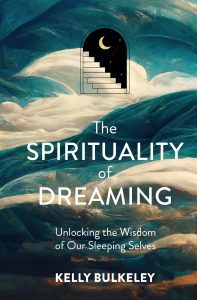

Excerpted with kind permission.

The Spirituality of Dreaming: Unlocking the Wisdom of Our Sleeping Selves by Kelly Bulkeley

Available now: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop.org, Broadleaf Books

Return to Ageless Spirit Contents Page

About Kelly Bulkeley, PhD

Kelly Bulkeley, PhD, is a global expert on dreaming and a psychologist of religion focusing

on dreams. With degrees from Stanford University, Harvard Divinity School, and the

University of Chicago Divinity School, he is director of the Sleep and Dream Database,

senior editor of the journal Dreaming, and former president of the International Association

for the Study of Dreams. His books include Dreaming Beyond Death, Big Dreams, An

Introduction to the Psychology of Dreaming, and Dreaming in the World’s Religions. His work

has published in the New York Times and TIME magazine. Bulkeley lives in Estacada,

Oregon.

The Power of the Immersive Arts to Catalyze a More Peaceful World

Featured photo | Immersive Art Show: ‘WERK in Progress’ | CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED

“For millennia, gathering around fire has been inspiring conversations that evoke the imagination, help people remember and understand others in their social networks, heal rifts of the day, and convey information about ways of being that generate productive behavior and relational trust.” -Polly Wiessner, Anthropologist

For those of us who strive to remain grounded, awake, sensitive, and conscious of what’s going on in the world today, it’s clear that we are living in a defining epoch of earth’s story, and of the story of humanity itself. We are witnessing precipitously rising levels of ecological degradation, species extinction, violent conflict, authoritarianism, and economic disparity.

In my journey as a lifelong musician, and as a social artist committed to crafting transformative experiences, I have aimed to bridge divides, heal wounds, realign spirits, inspire souls, and unify the fragmented aspects both within us and in the world around us. This dedication has convinced me that there is an evolving, more engaged role that the arts must serve in our society if we want to leave a world where our children might not only live, but truly flourish.

The Immersive Arts | Catalysts for Coherence

What exactly are the immersive arts?

Immersive art forms have the power to deeply resonate and transform people. They intentionally combine experiential elements such as music, spoken word, and poignant imagery to catalyze proactive changes in our emotional, somatic, and spiritual states. When the need for compassion and tolerance is more important than ever before, it’s vital that we explore new ways to tap into these arts strategies. They can subtly influence us to evolve into more holistic individuals, fostering open-heartedness, receptivity, and presence. As the world’s complexities mount, these forms of expression become essential bridges, guiding us towards more humane interactions and understanding.

For the last twenty-five years, I have devoted myself to creating immersive music, transformative and healing media, and musically enhanced art forms for health and well-being. My aim has been to inspire individuals to navigate both their professional and personal journeys with heightened mindfulness, resilience, compassion, and gratitude for the preciousness of life.

By integrating immersive arts modalities in a certain way, and at a certain time, I discovered they could help counteract the insidious numbness of social disengagement, potentially even rekindling an inner vibrancy. My hope is that this offering might embolden you to discover your own versions of the principles I share here, taking the time to notice what happens within you when you engage with immersive art forms.

What started me on this journey? I began playing the piano at five years old, when I could basically play any tune I heard. My formal education led me to institutions like Oberlin Conservatory where I focused on composition and ethnomusicology, (which was an early clue about my fascination with immersive art forms). After years of yearning to be a film composer, I mastered the art of film scoring —the craft of creating music that subconsciously resonates emotionally with the viewer, enhancing narratives and evoking emotions. By the early 1980’s, I had founded one of the most successful music production companies in the San Francisco Bay Area, and I spent the next eighteen years scoring national television shows, feature films, and commercials.

However, in 1998, after nearly two decades of success, a serious bicycle accident left me wondering if I would ever play the piano again. Not long after, I experienced a heartbreaking separation from my wife, with whom I was blessed to have a daughter. Having recently lost my father, the series of profound losses forced me to reevaluate my identity and purpose.

As luck would have it, I was approached at this time by pioneering healing team Michael and Doris Stillwater to explore how we might musically support those facing death, dying, and the end of life process. I ended up pouring my soul into the creation of some of the most powerful music that ever came through me. The project, entitled Graceful Passages: A Companion for Living and Dying, resulted in a globally acclaimed listening resource that carefully edited, curated, and musically enhanced the spoken messages of solace and support from world-class visionaries such as spiritual teacher, Ram Das, death and dying pioneer, Elisabeth Kubler Ross, renowned Buddhist teacher, Thich Nath Hanh, and nationally known Rabbi Zalman Shacter- Shelomi, to name a few.

As Graceful Passages became known more around the world, I dedicated myself to exploring more ways in which music and sound modalities could meaningfully impact the psychosocial healing process for patients, professional caregivers, family members and even our social networks and institutions, especially during the most significant passages we will ever traverse: birth, serious illness, and the dying process.

I wondered, can we harness these art forms to awaken multi-dimensional coherence on a personal and collective scale? How could these art forms play a role in fostering more peaceful and collaborative ways of engaging with each other, or even with ourselves during the most significant transitions of our lives?

Transformances | Awakening the Art of Interconnectedness

Over 400,000 years ago, humanity embraced the elemental power of fire in tribal rituals, awakening a primordial connection with themselves, the planet and one another. Beyond its practical uses, it was a communal touchstone, bonding people through shared rituals and gatherings, reflecting our connection with the cosmos.

In today’s digital age, many of us crave that deep-rooted connection. Yet, through immersive art modalities, we can harness online platforms to foster these primordial bonds around zoom’s digital “fires”. When we become more emboldened to engage in more heart-centered practices in professional contexts (supported by the science, of course) we can elevate our community gatherings into more unitive and memorable experiences. This approach embodies the principles of Emanuel Kuntzelman’s seminal compilation of essays entitled “The Holomovement”, which urges us to recognize the unity of all things, inviting us to actively participate in our culture’s transformative shift from the ‘ME’ of individualism to the “WE” of a global community ethos.

In a quest to spark this sense of global unity, I collaborated with author and visionary Sarah McCrum to produce a series of short, contemplative films that I entitled “transformances.” These short, evocative pieces were commissioned by Unity Earth executive director, Ben Bowler to provide the 2022 World Unity Week with transcendent shared experiences for the global online program. They served as immersive catalysts, inspiring thousands of people from around the world into a shared collective introspection. I share with you this one – Invitation to Unity, – which we extemporaneously created to share at the beginning of meetings, as an instrument for deeper, more connected and collaborative social interactions. Many of us observed that the effect was immediate; hearts opened, boundaries dissolved, and people breathed more deeply, fostering a collective environment of unity, connection and understanding.

In our age of divisive media and dwindling attentions, these art forms offer a rare refuge. They provide moments to pause, allowing participants to rest their cognitive minds while grounding themselves in gratitude and connection. It aligns us with the intrinsic interconnectedness that indigenous wisdom and modern science both recognize.

Imagine major institutions adopting such modalities—starting business meetings with two minutes of beauty and insight, cultivating an atmosphere of collective intent. When organizational leaders adopt such immersive formats, they champion collective well-being, for the good of the whole. Such artistic pauses have the potential to shift outcomes, broaden horizons, and reconnect us with our shared human legacy.

The Power of Vibration and Frequency

In the vast celestial dance that binds the universe, everything vibrates – from the palpitations of our hearts to the oscillations of distant galaxies. As our societies struggle through storms of change and uncertainty, an understanding of frequencies and vibration becomes imperative.

When we transcend entertainment, music can serve as a vibration-based vessel, navigating our way to ignite empathy, bridging cultural divides in shared communal experiences, and elevating our ability to become more centered in our hearts. And when we utilize music to help people connect the sacred stillness within themselves – in these times of over-stimulation, violence, and heart/mind fragmentation – we are given the chance to come back home to ourselves, to our sense of belonging.

Merely relying on intellect to address global challenges is a misstep. Real change emerges when the mind’s brilliance aligns with the heart, where the arts come alive acting as bridges, transcending cultural barriers, promoting compassion, and highlighting our shared humanity. In our fast-paced world, intentional pauses are vital. By aligning with the beautiful frequencies of nature, we can elevate individuals and communities, fostering holistic engagement and deeper connections.

Visualize city councils invoking shared purpose through multi-sensory experiences, or corporate boardrooms reconnecting to humanity before making decisions. Envision classrooms worldwide beginning with videos that foster mindful collaboration and curiosity. This is the immersive arts’ magic: recalibrating our collective intentions and awakening to what matters most for our collective well-being.

Now is the moment to integrate these immersive arts strategies to craft experiences that know no borders. Let’s start inviting artists who are dedicating themselves to applying these modalities towards the Greater Good to wield their transformative power, celebrating our interconnected essence. Together, we are called to resonate, align, and architect a harmonious future with a more courageous intention to allow these compelling experiences of coherence and beauty to have its way with us – aligning our life-generative intentions, awakening our interconnectedness, and catalyzing a felt sense of our unity with all life.

About Gary Malkin

Gary Malkin is a multiple Emmy award-winning composer, producer, public speaker, music & wellness consultant dedicated to harnessing music’s capacity to cultivate multi-dimensional coherence, especially during the most challenging transitions and phases of our lives. The composer/producer of the globally-acclaimed listening resource, Graceful Passages, (co-created with Michael and Doris Stillwater), creator of the successful Gaia streaming TV series, Islands of Inner Peace, & the co-creator of the widely respected caregiver audio series, Care for the Journey, Gary has just completed a fully realized stage musical about the miracle of birth and life with his collaborators, Lisa Rafel, and corporate leadership consultant, David Surrenda, Ph.D. called “Can You Hear Me? A story about sex, love and OMG Birth”. (www.CanYouHearMeTheMusical.com) Gary is a frequent guest on webinars where he introduces innovations in health, wellness, and personal/spiritual development. He is currently launching a new educational platform with spiritual guide, Hope Fitzgerald designed to help people cultivate resilience and grief literacy while mastering the art of change called You, Awake. (www.You-Awake.com) He collaborates with author/visionary, Sarah McCrum, on the creation of ‘transformances”, extemporaneously created immersive media resources for catalyzing coherence, holistic attention, and presence. A member of the Association for Transformational Leaders & The Evolutionary Leaders in good standing, Gary is committed to innovative ways in which deep listening to immersive arts resources can awaken higher states of unity consciousness. His websites are www.WisdomoftheWorld.com and www.You-Awake.com.

The River Threshold

The River Threshold

THE ENDING CAME three years ago, from the day before we went to the river. One version of the ending, anyway. She and I sat at a picnic table near a stream with a therapist who was also my uncle, and we said out loud in the summer June air that we couldn’t give what the other wanted. She said she couldn’t live with me anymore and be who she wanted to be. I said I couldn’t live indefinitely separate and fragmented. We said these things for the purpose of freeing each other, though freedom didn’t liberate like we thought. There have been numerous endings. Another ending came down by the river, three years and a day later.

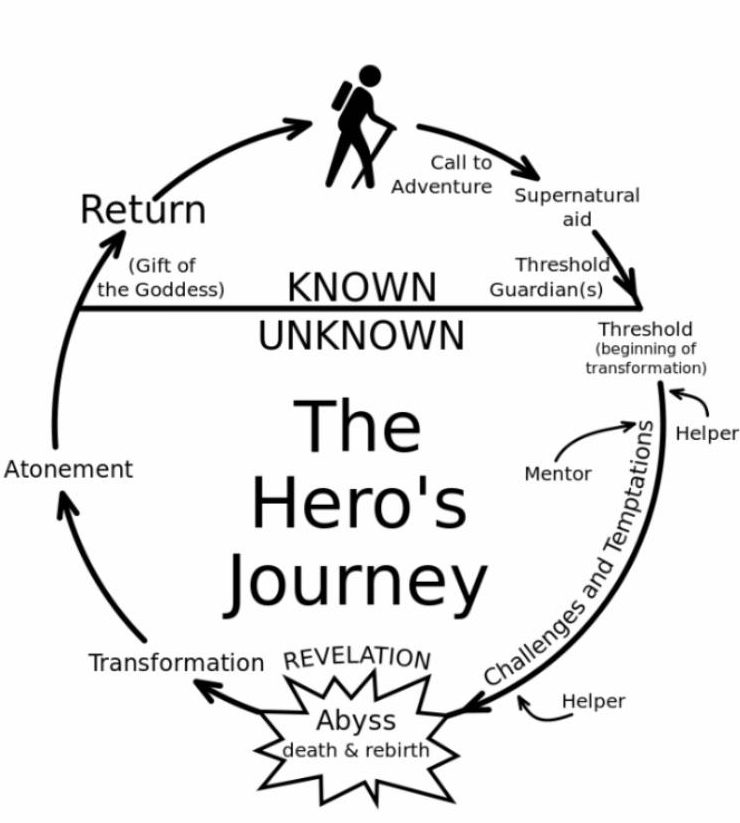

I’ve come to learn that transitions don’t often look like crossing a straight line. We circle back, or in some way forward, because circling is rarely a straightforward repetition of what came before. Instead, it’s a need to follow-up, continue, revolve. Grief is the emotion and the practice that accompanies irreversible transition – like final goodbyes, certainly all kinds of death, even births because all beginnings start with an ending.

Grief never completely goes away either, circling like water cycles, tears turned to thunderstorms, so pieces left from these endings didn’t get cleaned up, growing back together again in a hurtful dark. John O’Donohue, poet-priest from Ireland, pictured this process like being “ambushed” in the middle of daily tasks, when you think you finally have your heart back. Ambushes, small and large, kept surprising me, so I knew I needed to transition again, or make visible a practice of my transition. I felt ready to cross the threshold into the next time of my life, to leave behind an architecture I no longer lived in but perhaps occasionally squatted in, a memory palace where particular dreams still had a haunting life. As far as I was concerned, those dreams were welcome to remain encamped there, but I needed to move out.

Another poet, David Whyte, once remarked that the greater difficulty of a relationship’s end may not be leaving the person but leaving the shared dreams. No matter who or what comes next, he said, “no matter what species of happiness you would share with them – you will never, ever share those particular dreams again, with that particular tonality and coloration.” The end is an extinction.

But I was ready, really actually ready, for a new lease on a house of life. Life was moving on, as it always does, and I was mostly living it, though parts of me weren’t. I needed help to step through the doorway from this dying house. So two friends came to help me cross the threshold.

***

DAVE AND KYLE have been involved in all this from the beginning, from building that house, talking about its construction, to sitting in its loneliness with me, now helping me move out. Kyle and his wife Ginger even officiated the wedding, the ceremonial moving in, talking in the thick damp Arkansas heat about marriage as coevolution, which confirms the end is indeed an extinction. Kyle also first offered me the language of architecture for understanding the close intimacy, the careful maintenance, of inhabiting a marriage, and the many painful ways its borders can be violated. Dave was at the wedding too, reading Wendell Berry’s “The Country of Marriage,” a long poem about marriage as a place to adapt to, where general affection becomes particular love and an unfamiliar landscape becomes home. Country is a distinct metaphor from architecture, though similar enough that selectively re-reading the poem now eerily surveys a different country. Or perhaps the same one, now seen with grief after exile, anguish after extinction.

Instead of moonlit longing and restful union, consider insomniac nightmares held captive by the one you love: “I dream of you walking at night along the streams . . . You are holding in your body the dark seed of my sleep.”

Or the dizzying unknowing of why we were drawn together at all, times when no words came, ambushed instead with unexpected visions:

Was it something I said

that bound me to you, some mere promise

or, worse, the fear of loneliness and death?

A man lost in the woods in the dark, I stood

still and said nothing. And then there rose in me,

. . . the words of a dream of you

I did not know I had dreamed . . .

And then, with a twist of finality, twisted from the abundant freedom of self-release into the suffocating abandonment of drowning:

What I am learning to give you is my death

to set you free of me, and me from myself

into the dark and the new light. Like the water

of a deep stream, love is always too much.

Grief can do that to you, make you question everything you thought you knew or understand, like poems or people. Did I hallucinate all that tenderness? Those times that felt easy and comfortable? Did I make that whole country up?

Dave has crossed through this country in his own life. I’ve sometimes been jealous of his journey because he was much less responsible for its ending than I am for mine. But I no longer want to linger on the sharp fault line edges of my flaws, though the voices in my head, sometimes spoken in her tone, remind me of who I’ve been when I tried to defy my failings. It always takes at least two, but could I even be good, the voices asked, when I’m so imperfect? Doesn’t imperfection mean I deserve what I got? “Flickers of guilt kindle regret/For all that was left unsaid or undone,” wrote John O’Donohue about the heat I’ve felt. Guilt is a real condition, regret a necessary emotion, but I no longer hate myself and I want to keep it that way.

My friends came for a June weekend and we talked, hiked, looked at my gardens and the nursery where another friend and I grow trees and ourselves. That first night, successively drinking whiskey, bourbon, and gin, I told them that I couldn’t shake the image of threshold, its old word-roots grown from a double sense of treading and separating, walking and winnowing. Crossing over something into somewhere else, returning changed to a changed place. In her manual on power, Cyndi Suarez reminds that rites of passage always “begin with a threshold – a challenge one cannot meet without transcending one’s current idea of oneself”: a strategy for meeting needs no longer works, a story no longer rings true, an initiatory move into a new age. That transcendence was what I was looking for. The earth also has thresholds, from one biome to the next or when slow small disturbances finally crest into quick changes. That’s where I was, at the biome doorway. I needed to physically walk through a threshold, to separate myself from the past by treading, not just talking about it.

They listened, asked questions. Dave wondered if there was anything else I needed to say to her. I knew there was, especially towards the very end, but I’d never really let myself speak directly to her those words out of fear of making it worse, out of fear of sounding like I was avoiding myself. I spoke countless things to her in our short shared life: some beautiful, some vulnerable, some cynical, some that still taste bitter in the mouth. After too much time defending and deflecting, the bitterness baked into a story solely filled with all my dysfunctions and imbalances. Usually all I could see were those sharp fault lines, all my worst moments carved in stone. Dave told me that a grief ritualist suggested to him that he say his unsaid words out loud, as if to his former partner but directed to a rock. Your soul, the ritualist explained, doesn’t know the difference between the firmness of the rock and the firmness of her. Your soul simply needs to speak. Maybe, Dave added, I also needed to say out loud a counter-narrative to the bitter stone story.

I told them I wanted to be by the river. I’d spent a lot of time there, crying my grief into the flow, ritualizing my return to this chosen home, joyful play with friends floating in the current. The river felt right. Partly because I think emotions move like water, and grief is like their river. My friend Karla McLaren, loving guide to emotions and empathy, says that grief is unlike sadness, which arises to help us let go of what’s no longer working but we could choose to hold onto. Grief arises when something is actually lost, a never-to-return loss, taking us down to the deep places because they are the only places left to go. Grief moves at extinction events, when things die. I decided to take grief to the South Fork of the Shenandoah, to the river I know.

Before Kyle and Dave came, my grief had already moved me to the river, stepping in, lifting my feet, floating further down. I swam over to a shelf of rock cropped out from the steep bank beneath the road. I undressed, reentered naked, with my grief, to midriver where the current swept swiftly. I bore my feet down into the stone and used an old drifting mop handle to anchor myself. I didn’t know what I was going to say, with so little to draw on in my so-called culture, this whitewashed colonizing culture, death-denying and therefore grief-avoidant. Martín Prechtel says that it “is a terrible source of grief in itself to not be able to grieve.” So I made up what I needed to say on the spot. “So be it,” wrote Cormac McCarthy in The Road. “Evoke the forms. Where you’ve nothing else construct ceremonies out of the air and breathe upon them.” I constructed a ceremony out in the otherworld of water and I screamed it under the thudding slip of the current.

Unable to grieve, we’re haunted by what we’ve lost, trapped in-between, never separated enough from the loss to tread to another union. Grief can’t be outrun, outthought, though it can be outsourced, pushing the burden to someone and somewhere else with unforeseen consequences, grieving turned to grievance. Grief is a powerful enough riverine force that it needs ritual, instinctive or inherited, to help responsibly shape its course, charting the changes that always shape our lives. Francis Weller identifies two gifts ritual offers grief: containment and release, the safe holding and the free letting go, a kind of vessel for pouring. Ritual doesn’t erase wounds, doesn’t forever remove the burden of grief, but it maintains and tends, helps us offer gratitude where we can, provides regularity for the maintenance and tending. Repeating a ritual doesn’t mean anything is broken. Maybe my grief wasn’t stuck, just unfinished, maybe never quite done, the ritual never completely over. My desire for a threshold was a need to find my ground, to create an altar or shape, like the river itself. An actual river to correspond to what Weller names “riverbeds in our soul” carved by sorrow.

Maybe, I told Kyle and Dave, we could make a threshold on the ground with sticks or stones like my fault lines, dismantling them once I crossed to recognize the movement. But the image still looked too much like crossing a straight line, even though taking it apart afterwards disrupted the linearity. Whatever the threshold, it needed to be actual, made with the world itself. Dave encouraged me to write down what I needed to say, then burn it. Then Kyle said maybe the river is the threshold. We should cross it and on the far shore make a fire and burn the words there and then cross back over. The flame and the flowing moving place were to be the doorway in time, a grounded sense of time, which moves in cycles and not lines. I said that’s what we needed to do.

***

Moving in circles, I had carried grief to the river before and yelled an underwater ceremony. I had also burned words before, a disposal to signify an end. Nothing broken, only maintenance and tending, moving in circles. Six months after the picnic table ending, I moved out of the Shenandoah Valley to be near family, to separate and heal, maybe to run away. In the ensuing weeks I couldn’t sleep for feverish turning, fitful weeping for her. For months prior I carried a stack of printed emails, ostensibly to provide a thorough history for therapists, but also somehow evidence of chaos-making communication, a paper trail to defend myself.

One late night I evoked the form of a ritual. I typed her a new email, this time in a different tone than before, no more ands or buts or also, simply “Yes, I am sorry.” No excuses or defenses, just responsibility for my part without expectation and a list of all the gifts she’s given me. I told her I felt more broken open than ever before, remembering all the instances when I was demanding, stubborn, condescending, overly assertive in my presence and desires, the ways she then backed away, lay low, withdrew in response. I told her I felt sick at my immaturity and misunderstandings that led to arguments, silences, turnings away. I could taste the dismissing tones in my mouth, could hear their off-key pitch, could feel their imprint in the squint of my face. I told her I was sorry. I apologized because I needed to so I could be who I wanted to be. Because apology is a kind of naming. Because sometimes we do wrong things, and it’s important to admit them. Then I shaved my beard, cropped my hair close, stripped, and made a fire in the yard. I burned the hair and I burned the paper trail so I couldn’t follow it again. The ritual did something only it can do, what talk therapy can’t get at. After sending her the email and burning the papers I slept more soundly than I had in recent memory. I also still had my grief when I woke up.

At some point, a time between the burning in the yard and the burning by the river with my friends, after many more things had been said, she also wanted a ritual to end our marriage. She told me she wanted to break the wine glasses I gave her for our first anniversary, at the homestead where our marriage lived and struggled the longest. After a week of trying to convince myself to do it, I replied no, thank you. I understood, even respected, the intention, but the tone and the act felt nearly violent in the midst of unrequited words, unreciprocated responsibility, and premature for what I actually wanted at the time but felt was no longer possible: to repair all this shit, to resurrect extinct dreams, to be with her light and warmth.

***

I feel some awkwardness writing all this down now, a little embarrassed at the melodrama of it. Perhaps that’s true of intimate moments of transformation told aloud. I’m tempted to temper the personal focus, abstracting my experience into a general meditation on marriage or the grief of this time, from viruses to civil war vibes. But that’s not what this story is about. I’m attempting to write vulnerably, a version of truthfully, without self-pity but with detail to the ritual of grieving heartbreak and mistake. I don’t want to distract from that with generalities or dilute it by drawing attention to all the ways I was hurt too. Each ritualized time felt ordinary, almost exactly natural, an invitation to feel deeply without selfishness. Weller believes that sorrow connects us to the world, the personal to the planetary, and all this personal talk of endings does make me think of the planetary ones. He says that grief finds us through five gates: the reality that we lose everything we love; the places that haven’t known love; the loves we expected but never received; the sorrows of the world globally known but individually felt; the unmetabolized grief inherited from our ancestors. Gates are, after all, thresholds, and all of Weller’s gates involve separation and treading. They all weave together the solitary and the social, the personal and the pandemic.

As for embarrassment, Prechtel affirms that this is grief’s natural and necessary sound, indifferent to misunderstanding. Purposely done, he believes, true and free grieving as an entire people could revive entire cultures, it could “make life more deliciously alive.” And Grief is in fact the best friend of Praise, dwellers in separate chambers of the house of Love, which is the heart. “Grief is praise,” Prechtel vows, “because it is the natural way love honors what it misses.” Both “are very practical versions of love in motion,” a river not a bog.

We can never praise if we never grieve.

***

WE DROVE DOWN out of town to the river, in the gray spray of rain. Parking roadside, we descended a footpath to the wide floodway, filled with trees along a tributary creek. The green of the place met my vision and focused me down under the canopy to the cool wet air and earth. Dizziness clouded me in recent weeks, unable to steady my gaze, as if I were looking through a screen or the long lens of a telescope. But the green and gray, the silvered brown of the river, brought me to attention.

We treaded the soft last path to the bank, colonnaded by rows of Sycamore and Cottonwood, some of the tallest and roundest of either tree I’ve seen in this great valley. Every time I walk that path I stop short before them, each time struck by the size of their immense gorgeous growth. Tree size isn’t a good gauge for age, and both Sycamore and Cottonwood grow very quickly, but those trees have certainly been there a while. Some of the trunks would take all three of us to wrap our arms around. On this day, Sycamore and Cottonwood appeared out of the gray like gatekeepers, druidic in their rooted silence, calm in the lengthening rings of their lives that regard as restless my sense of patient time. Prechtel says grief “is what living beings experience when what or whom they love dies or disappears.” Living beings: more-than-human, more-than-mammals, more-than-creatures-with-brains. I wondered what loves those trees have seen disappear, and what arboreal grief sounds like. I touched the living barked beings closest to the path as we passed, toward a ritualized past.

I felt my stomach coil as we came out of the trees to the water, heard before seen. Not a resistance to what we were doing, but a hesitance. I had symbolized my grief here before to make this place home, but the invitation for grief to come in the company of these friends, to cross a threshold at and as this river, moved down in my body with appropriate gravity. What moved in my gut also seemed to move through the land, circulating through me and the water and wind, then grounding itself in the imagery of a house, with a doorway I needed to cross to make a new home, one I was already preparing for and should step into, resolvedly, committedly, readily. I was now in a relationship with a wonderful person, Christen, and we had been dreaming about that new home, both relational and physical. But I hadn’t been fully ready to plan, with dates and announcements and communal ceremonies to witness the commitment made, which was another threshold I would need to cross. First, I needed to step over this one, to separate and tread, winnow and walk, in a communal ceremony with my friends.

I looked at the river and questioned if we should cross. The current’s clip was swift. Not dangerously so, but enough that we needed to move carefully and alertly. Dave found a soda bottle with a twist-on cap and shoved into it a lighter, a pen, and some paper. We stripped to our boxers and I descended into the cool water, kept a foot on rock until I was part of the way over before shoving off and plunging at an angle for the river to sweep me across. A thick stand of young Sycamores greeted me on the stony sandbar, with river’s fast flow behind me and slow pools ahead before the actual bank. Dave and Kyle followed and we crossed the shallow divide beyond the Sycamores and came to the far shore. For our purposes, we came into the otherworld.

The gray rain gave the world the pallor of ash. Lament was in the air, rain falling steadily like a kind of sadness. John O’Donohue heard in water the “voice of grief.” In one praise poem, he hailed the “grace of water,” its “liquid root” working through “the long night of clay,” and also the “humility of water,/Always willing to take the shape/Of whatever otherness holds it.” The water from the sky shivered into the water through the land, expressions of a cycle turning over and over into one another. They met, flowed with persistence, a quiet but firm insistence that this day is what we had to work with, the water and the grief will not be unbearable, but they’re also not going away. So we made our ceremony with what we had, and I tried to imitate the humility of water by taking the shape of its own liquid root.

I separated from the shore and ducked further inland, just enough to where I had some solitude. I found what seemed like a path, another shape humbled by the flow of water. I knelt, opened the mason jar in my hand that held some torn pieces of envelope and biochar, wood from the stream in town cooked down into carbon to absorb nutrients. I carry the jar in my backpack, my homemade version of incense or anointing oil. When I remember, I leave a sprinkle at the feet of plants where I harvest food or gather seeds, or at the landfill when I contribute to its leaching burden. Biochar takes what is often discarded and turns it into a sponge to hold fertility, which is a kind of memory releasing over time.

I enclosed myself in a circle of char, smeared the stain on my fingers onto my forehead. Then I wrote. The rain quickly dampened the paper, but it took the words I needed to say. I wrote to her as if I spoke to her. I said the words that still stung me, the stories still hounding me, the regrets still hanging over me. But the only water that fell was the rain. I felt the heaviness of grief’s gravity pulling at my face, but my tears remained up.

When I finished writing, I slowly walked toward the bank. I smelled smoke, then saw clouded curls of it. Despite the damp, my friends had made a fire beneath a Sycamore and a Walnut. Between the two trees, past floods had packed bark, leaf, and twig into a dam from which Dave pulled enough dry material to ignite with the lighter. More sticks and small branches fed the smoky flame, the smoke becoming part of the overhead gray. We began placing rocks around the fire’s edge and huddled close to feed and feel its small warmth. I bent over my knees, elbows tucked down, face close to wet earth, holding wet paper that held the marks of my grief-wet words.

I read them aloud, parting the rain with their clearness, and my tears broke through to fall with the rain. My body had been holding more grief, a flow in need of moving before I had enough room for my life. I could have forced my way forward with it stuck, but I’d done that before, trying to be ready to move on when I wasn’t prepared, and I knew eventually grief would flood me again. The ritual made room, both to feel and for the feeling to pass on and make room for something else to move in. “It becomes hard to trust yourself,” wrote the again-wise O’Donohue.

All you can depend on now is that

Sorrow will remain faithful to itself.

More than you, it knows its way

And will find the right time

To pull and pull the rope of grief

Until that coiled hill of tears

Has reduced to its last drop.

My tears kept falling, uncoiling themselves as I spoke words I’d wanted to say to her but never fully said, now without concern for consequences. No attacks, no excuses, only honest and unhedged, stitching two stories out of the fault lines. Kyle and Dave didn’t react, saying nothing, maybe listening, watching the fire and offering company.

I finished what I had to say and crumpled up the sorrowed paper. I tossed it into the fire and despite the damp it too caught the light. I breathed audibly, a gasp of relief as those words turned red, then white into ash, then were gone. Dave gently stacked more of the river-racked tinder from between the two trees, our huddled shapes under them converting them into altars.

I heard the river rumbling, somersaulting in currents down toward the sea. Everything around us – the leaves, the rain, the airy nutrients – gravitated downhill with the river, including our tears, including my grief, anything with the slight weight of loss. O’Donohue calls this the “courage of a river” continuing to believe in the gradual descent of ground. I had no more words of my own, so I sang a song to match the plumb line of that courageous direction, my voice cracking from the strain of being honest. Dave knew the low rolling tune so he sang too, and Kyle hummed until we sang through the cycle again.

I heard the river rumbling, somersaulting in currents down toward the sea. Everything around us – the leaves, the rain, the airy nutrients – gravitated downhill with the river, including our tears, including my grief, anything with the slight weight of loss. O’Donohue calls this the “courage of a river” continuing to believe in the gradual descent of ground. I had no more words of my own, so I sang a song to match the plumb line of that courageous direction, my voice cracking from the strain of being honest. Dave knew the low rolling tune so he sang too, and Kyle hummed until we sang through the cycle again.

We sat a few minutes longer, wind shushing through us, until I said I was ready. The fire died enough that I could scoop some white ash into the jar of black char, a symbol of dark carbon absorbing the nutrition. We spread the stone circle back out and let the rain dowse the embers. I picked up a small smooth stone, warm to the touch, about the same size as one I plucked from the shelf in my apartment at the last minute before driving to the river. The one she gave me after the last time she left, with a note telling me she was giving me this small stone, “a little guy” that she’d put a lot of love into.

I didn’t want to let it go. I wanted to keep holding it with a special place on my shelf-top altar. I could have done so and doing so wouldn’t be wrong except I knew it was no longer right for me. The small stone was just large enough to block the threshold into the next room, the room made by walking and moving the grief and that one small stone with love in it.

Kyle and Dave crossed the river first, fumbling in the rapids with goofy grins and laughter. I waited in the otherworld, crouched on the rock-rolled shore beneath the Sycamore stand until they crossed. Then I waded into the same river where I had shouted my grief the summer before. I swam to midriver, slipped underwater to the underworld, braced myself against the turning current. I opened the jar and poured the ash and char into the pastel river, bending up by the mountain but carried down to the sea. I came up out of the river and across the threshold.

I later learned that Karla McLaren suggests five rules for a good ritual. First, be clear about your intentions, to know why you’re having the ritual in the first place. Second, mark a clear beginning, with a phrase or sound or movement, so you know what came before and what comes after. Three, define the location of your ritual, with clear boundaries to know where the edges are in time and place. Four, feed and tend your altar or shrine, to stay alert and aware for as long as the ritual lasts. And five, close the ritual with intention, with a phrase or sound or movement, clean up what needs cleaning, remove what needs removing, and celebrate because good work has been done.

The three of us sat on the trunk of a branch, worn smooth by water. I retrieved a pipe from our bundle of shirts in a stump, along with a jar of dried Mullein leaves. We lit a small fire in the bowl, passed it between us, puffing herbal smoke into the smoky rain. We didn’t talk, just smoked, a quiet sober celebration at the ritual’s end. Dave and Kyle grabbed their clothes and I stood at the water’s edge, small love-filled stone in hand. I let it go in an arc to midriver where it crossed the surface line of the water, following the liquid root down, a disposal to signify an end. A story in firm stone to heal a fault line. Maybe my grief wasn’t stuck, only unfinished. Maybe never quite done.

We passed along the soft path back up the creek, beneath the cathedral Cottonwoods and Sycamores. Kyle hugged us, got in the car back to Connecticut. Dave and I drove up out of the river’s floodplain and back into the heights of town.

***

ALMOST FOUR MONTHS later, Kyle and Dave came back to the watershed, only a score of miles upstream from our river threshold, for my wedding ceremony. The two of us, Christen and I, decided a few weeks after the ritual that we were ready to move into the next room, the biome beyond the many small disturbances. We stepped below the spring house and across the small stream that cuts below our new home, carrying the water down toward the creek that enters the river at the point where my friends and I crossed to release my grief. She and I stepped on stones over cool water to the gentle otherworld bank, to plant two little Willows while loved ones sang to us, waiting for us to cross back from our past grief, from the future of those Willow roots, to the present of our lives on the other side.

About Jonathan McRay

Jonathan McRay is a father, farmer, facilitator, and writer in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. He grows beautiful and useful trees that cross-pollinate food sovereignty and ecological restoration with Silver Run Forest Farm, a riparian nursery, woodland collective, and folk school practicing agroforestry, watershed health, and restorative justice. As a facilitator and mediator, he supports grassroots groups and community organizations through conflict transformation, popular education, and participatory decision-making. Jonathan is also learning to give up erosive perfectionism in favor of joyful growth.

Hope Leans Forward | The Body as Grounded Wisdom

Hope Leans Forward | The Body as Grounded Wisdom

The body is our house—and how we live in it and where we

occupy it are uniquely ours, as well as being part of the common

human experience. The body is a treasure trove and an exquisite

vehicle for our practice of waking up and being with what is.

—Jill Satterfield

My grandmother, Lillian, like my mother, was a domestic and tough, but she also had a tender side. I absorbed her toughness more than her tenderness, even though I admired her tender side. When they came, the tender moments took me by surprise, and I cherished them. We had a ritual every week where she would get out the foot basin and the Wray & Nephew overproof white rum. My job was to wash and massage her feet with the rum. She believed white rum would cure her debilitating arthritis, and I felt special, being asked and sharing the time.

Her feet were muscled, boxer-like and built, evidence of a hard life of little ease. At that time, she was well into her seventies, youthful by today’s standards, but back then, she was worn out, nearing the end of her life. Consciously or not, I absorbed many messages from this ritual. Two stand out. First, it’s exhausting to be a Black woman; it runs your body into the ground. Second, self-care is essential, indispensable when life is hard. She deserved, she earned, this moment to care for herself and for her body.

This memory lingered in me when decades later, following an intuitive sense that I needed to care for myself in a different and unaccustomed way, I began studying Kundalini yoga. My work was punishing my spirit and my body, and I needed to find a way out of the mess. I had worked myself into uterine fibroid tumors that eventually contributed to several miscarriages. While I received medical treatment, there was no safe place for me to talk about what was happening to my body. I joined a support group for women who had experienced miscarriages, but I felt isolated as the only Black person in the group.

To heal myself from the pain, I created rituals of healing, much like my grandmother did with me. I attended retreats for women who had experienced miscarriage. I lit candles. I prayed. I read books on loss and grief. Yet all this and more couldn’t dislodge the grief that had me like a straitjacket. It wasn’t until I traveled to Japan on the eighty-eight-temple pilgrimage of Shikoku that I began to heal, an experience I described in my first book, The Road That Teaches: Lessons in Transformation through Travel.

Our pilgrimage began in Osaka, and we took the high-speed train to Mount Koya, or Kōya-san, a World Heritage Site and the birthplace of Kobo Daishi, the founder of the Shingon school of Buddhism. The pilgrim officially begins at the temple gate at Koya as a symbolic act of commitment. Passing through the gate, the pilgrim takes a vow to complete the pilgrimage, not just for themselves but for the benefit of all beings. With moss-covered rocks, the scent of incense, the sound of temple bells and fast-moving water down forested hillsides, Mount Koya is a “thin place,” where the material and spiritual world meet.

As I entered the graveyard and passed through the temple gate, I bowed. The cemetery was partly dedicated to Jizo Bodhisattva, the Japanese deity said to aid pregnant women and travelers. Jizo is the caretaker of deceased infants and children, including fetuses lost to miscarriage and abortion. Hundreds of stone statues of Jizo line the cemetery stone walls. Some wear handsewn capes and hats, others stand atop mossy rocks, and still others receive a love note written in longing and loss. A damp teddy bear, a bouquet of faded flowers, yet another story of loss and love.

For years after the miscarriages, I felt barren and broken by the loss, shame, and guilt. There was a ragged, dispossessed part of me that I couldn’t shake. Here in the cold spring dampness of Kōya-san, my loss and grief were acknowledged and shared, not by a handful of people sitting across a table in the basement of a hospital support group, but openly by a culture and a people. I sensed that those in the cemetery around me understood and, unlike the support group, made space for the grieving to be and to breathe. The Japanese people recognized and honored the grief of miscarriage and abortion through this cemetery and these healing rituals, which said to me, What happened to you happened to us. What you’ve done, we’ve done. You are loved here. You can heal here. All of you is accepted, loved here.

The loss from the miscarriages is still there, though less so; less chokingly devastating, but there. Looking back now, I realize that in some ways, the miscarriages were fueled by fear of further loss, of the uncertainty and fragility of relationships that held me back from loving and being loved. I kept second-guessing myself with questions: Was it my unrelenting drive to “succeed”? Was it the running from poverty and toward a legal career? Was it the years of weight training and intense exercise that had eventually molded my body into an impenetrable shape? The one thing I did know was that the healing I was seeking wasn’t in the support groups with people comparing and one-upping their loss. The beginning of my healing started in a very unlikely place, halfway around the world in a cold, damp cemetery in Japan, where the collective grief was free to breathe and be held by everyone. With all this, I arrived at my first Kundalini yoga class: tough-minded and tough-bodied.

I started studying and practicing Kundalini yoga at about the same time I began studying meditation in the Plum Village tradition. Yoga and meditation were part of my healing process after a surgery for the uterine fibroid tumors, after my painfully short first marriage, and while pinned beneath the weight of my Big and Important Job as a lawyer-lobbyist.

As I began to practice yoga, one of my first realizations was that my breath and body were frozen and rigid, like a block of ice. I could barely turn my spine from left to right. My fingers dangled a couple of feet away from the ground as I folded my body forward, my hamstrings screaming with tension. Most shockingly, I couldn’t feel my breath.

My years of living an intellectual, success-driven life set me up for intellectual breathing. I was largely in my head, cut off from the wisdom of my body. My breathing was frozen. I was so focused on “getting there” as opposed to “being there,” and had spent so much time trying to outrun poverty and prove my own worthiness to myself and others that I had forgotten how to breathe. My breath, mostly in my upper chest, was shallow, and I recruited the secondary respiratory muscles of the neck, upper chest, and shoulders instead of the primary respiratory organ of the diaphragm, abdominal muscles, and the intercostal muscles between the ribs. I had forgotten how to breathe with my whole body.

In studying yoga, I recognized and acknowledged patterns from decades of living remotely in my body. In law school, I studied torts, evidence, commercial law, but I learned nothing about my body, the breath. And years of working hunched over a computer left me nearly inflexible in body and spirit. Though breathing fully and completely lies at the very center of life, I was stuck in a shallow pattern that mirrored my stressful life. With Kundalini yoga, I set out to reclaim my breath and my body.

Before I began Kundalini yoga, I experienced chronic pain in my jaw, upper back and shoulders, and sides of my neck from poor breathing and a habit of bracing myself, which even affected my mood. Unconsciously clenching muscles in the anal sphincter affected my back and shoulders. I was hyper-vigilant and impatient with a nasty edginess. Even today, when I have a flash of impatience, I still catch myself and notice that my breathing tracks the feeling in my body. I feel my breath weak and uneasy.

After my return from Japan, I began reading the books of Judith Hanson Lasater and Donna Farhi, long-time yoga teachers, and then took breathing-focused classes with them. In The Breathing Book, Farhi points to several important characteristics of “free breathing,” which helped me understand the crucial, essential link between the mind, the body, and the breath. It was time to practice, even though I had plenty of resistance and plenty of skepticism. I’d lie on the floor with my knees bent or resting the back of my knees on the edge of a chair and listen to myself breathe. I felt dumb, like “This is a total waste of time.” I thought, “I could be squatting or deadlifting weights. I could be walking seven or eight miles, uphill. What am I doing here?”

I’d force myself to lie there being still, waiting for something, anything to happen, waiting for a signal. I stuck with it, and after a couple of weeks of this “do nothing” breathing exercise, one day I felt something. It was my breath but not in my chest and shoulders. I felt it at my reproductive organs and below the navel. It was like my body was opening and closing to the rhythm of my in- and out-breath. Oscillating, at first the breath was moving my tailbone and then rolling upward and outward to my shoulders and hands and then downward and inward to my legs and feet. Like boneless seaweed, the breath moved higher and lower, left and right, circular and in, multidirectional, then becoming calm and effortless. Through quiet attention, patience, and perseverance, this bruised and battered part of my body was beginning to move in freedom and harmony.

Slowly, incredibly slowly, I was being invited to trust and allow the breath to emerge and to release naturally. As I practiced this “do nothing” breathing, these words came to me:

Allowing ease and release

Allowing body to soften

Allowing breath to know ease

Allowing kindness

Allowing in-breath to meet the out-breath

Allowing pause between the in- and out-breath

Allowing lungs to be free

Allowing belly to be free

Allowing the heart to be free

Rise

Fall

In

Out

Deep

Slow

Breath.

As I invited the breath, I was being invited to inquiry, not only about my body, but also about my hard-driving life, my values. As I began with this foundational breath and body awareness practice, I retrained how I was breathing. And as I did, a lot of my chronic neck and upper-back pain was alleviated. But more importantly, through the breath, the real me—the vital me, the whole me—was rediscovered. I had found a different kind of intellect, a wisdom from inside my body that felt whole and right.

* * *

“Do nothing” breathing is now one of my most important rituals and I offer it to individuals in my coaching and leadership work, as well as to groups on retreat. Several years ago, I was invited to open the annual conference of Spiritual Directors International with my dear friend Karen Erlichman, and we offered a version of the “do nothing” breathing. The grand ballroom was packed with maybe six hundred people all practicing the breath I stumbled upon at the height of disconnect from my body. Most people were standing with their hands on their belly, breathing. Some people were laid out on the stage flat on their back, eyes closed, following this essential breath back, way back to an essential part of themselves. Still others sat in chairs, gently swaying from side to side. It was beautiful. Here’s what we did:

“Do Nothing” Breath Inquiry Practice

Choose what’s best for your body to sit, stand, or lie down, and allow yourself to get in a comfortable position.

- Allow your eyes to be open or closed. Notice what feels most comfortable.

- Notice the shape of your body without judging yourself.

- Feel your feet on the floor if standing.

- Feel your legs, hips, torso, arms, chest, face.

- Allow your spine to relax, and become aware of the back, sides, and front of the body.

- Bring your attention to your breathing.

- Feel the breath come in and go out.

- Notice and feel the in-breath.

- Notice the pause between the in- and the out-breath.

- Notice and feel the out-breath.

- Feel the belly rise and fall.

- Practice gently bringing your attention back to the sensation of breathing; feel the rise and fall of your belly.

- Feel yourself breathing in and out.

- Imagine your body like boneless seaweed with roots, grounded yet totally free.

- Notice how you’re feeling physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually.

- Take a moment to sense your breathing and ask yourself, “Where do I feel my breathing?” and simply wait.

- Return to the question over and over: “Where do I feel my breathing?” Let whatever perceptions you have be here without editing them. Don’t discount tiny movements.

- Place one hand on the belly and the other at the chest or any place on your body, if that’s appropriate for you, and feel the movement of the hand at the belly and at the chest or that part of your body.

- Ask yourself, “What does my breath feel like?” and simply wait without judging yourself. Gently keep returning to this question: “What does my breath feel like?” Become aware of words or images that might arise to describe your breath. Again, let whatever perceptions you have be here without editing them.

- Return your attention to the body and mind, gathering an impression of how you are doing at this moment. There is no need to change or edit this moment.

- When you are ready, stretch gently to close this practice and notice how you feel.

My grandmother had little chance to practice “do nothing” breathing. Yet our ritual of washing her feet with white rum taught me that you’ve got to make doing nothing a major priority, no matter what. And I do and will continue to practice that for her now.

Excerpted with kind permission from:

Hope Leans Forward

Hope Leans Forward

Braving Your Way toward Simplicity, Awakening, and Peace

by Valerie Brown

PUBLISHER Broadleaf Books

PAGES 275

PUBLICATION DATE November 8, 2022

Recipient, Nautilus 2023 Gold Award for Eastern Spirituality

About Valerie Brown

Valerie Brown a Buddhist-Quaker Dharma teacher, facilitator, and executive coach. A former lawyer and lobbyist, she is co-director of Georgetown’s Institute for Transformational Leadership as well as founder and chief mindfulness officer of Lead Smart Coaching. She is an ordained Buddhist Dharma teacher in the Plum Village tradition, founded by Thich Nhat Hanh, and is a certified Kundalini yoga teacher. In her leadership development and mindfulness practice, she focuses on diversity, social equity, and inclusion. Brown is an award-winning author whose books include Hope Leans Forward, The Road That Teaches and The Mindful School Leader with Kirsten Olsen. She holds a juris doctor from Howard University School of Law, a master of arts from Miami University (Ohio), and a bachelor of arts from City University of New York. Brown tends a lively perennial home garden in New Hope, Pennsylvania.

A Cosmic Twist

A Cosmic Twist

Look up into the clear night sky, and after a time you will perceive how the stars rotate around a central axis, as if on a great wheel. The ancients saw this rotation as the movement of a cosmic spindle, with its whorl in heaven and its shaft, the axis mundi, invisibly extending down to earth. Life and destiny were the threads spun by this spindle, the fabric of the world woven by the movement of sun and moon, stars and planets.

This image is remarkably universal. In The Republic, Plato beautifully describes the “spindle of necessity,” suspended from a rainbow-colored shaft of light, with an eightfold whorl of stars and planets, all singing in eternal harmonies, while the Kogi people of Colombia tell how the Mother Goddess set up a giant spindle to penetrate all nine layers of the just-created earth, still soft and unstable, which then solidified around it. The cosmic spider spins the world into existence in myths found all over North and South America, Africa, and Asia, and fate-spinning goddesses include the Germanic Norns, the Greek Moirae, and the Roman Parcae. In an apocryphal story, the Virgin Mary spins and weaves the veil of the Temple, which is the cosmos. 1

The primal activity of thread-spinning has become distant and unfamiliar to us today, through the mechanization of fabric production, but it is not difficult to recover a sense for it. Take a lock of sheep’s wool, which you can obtain from a craft store or fiber market, or perhaps even in its raw condition from a farmer. Carefully tease and puff out the short fibers until they form a fluffy ball. Starting at one point on the surface of this ball, pull out a small portion of the fibers, twisting them with your fingers. Keep pulling and twisting, gradually taking up more of the fibers, until you have a length of thread, or more likely a lumpy, unwieldy strand of thick-and-thin yarn—which may not be beautiful, but is nevertheless a transformation of the disorganized substance you started with.

You’ve just practiced one of the oldest of human handcrafts, dating back around 30,000 years, which, as we have seen, represented for our ancestors a human mirroring of the forces of the cosmos. When people became spinners, they were not merely serving a mundane need for clothing and shelter; they were establishing themselves as creators, bringing their own activity into play to shape the products of nature, no longer passive recipients or victims of natural events. Spinning brings a cosmic “twist” into the raw materials we encounter upon earth, giving them strength and continuity, and in so doing, the soul of the spinner is transformed, as well.

When we spin a thread, we are actually creating an extended, attenuated spiral, and the spiral is a cosmic form that repeats itself on all levels of our living world, from the shape of our galaxy to the helical structure of our DNA. More tangibly, spirals can be found everywhere in nature, in whirling clouds and swirling water, in unfurling fern fronds and seed-filled sunflower heads. Even the hair on the back of our own heads grows in a spiral pattern. The uneven, rotating crimp of sheep’s wool is actually what makes it much easier to spin than smooth fibers like cotton and flax; the wavy fiber complements the movement of the spindle, and locks the spiral structure in place.

When we spin a thread, we are actually creating an extended, attenuated spiral, and the spiral is a cosmic form that repeats itself on all levels of our living world, from the shape of our galaxy to the helical structure of our DNA. More tangibly, spirals can be found everywhere in nature, in whirling clouds and swirling water, in unfurling fern fronds and seed-filled sunflower heads. Even the hair on the back of our own heads grows in a spiral pattern. The uneven, rotating crimp of sheep’s wool is actually what makes it much easier to spin than smooth fibers like cotton and flax; the wavy fiber complements the movement of the spindle, and locks the spiral structure in place.

The spiral dances of the moving stars and planets were tracked by ancient astronomers, and humans very early took up this motif in their artworks and cultic images, chiseling spirals on passage tombs in Ireland and rocks in the Arizona desert, carving them on Chinese jade animals and the Ionic column capitals of Greece. The originators of the art of spinning must have felt that they were echoing the forming of matter by cosmic forces.

Tools were soon invented to make the process quicker and the products more consistent. Probably first a stick was thrust into the fibers, which could then be rolled down a thigh instead of doing all that tedious finger-twiddling. This is something you can also try out yourself, using a small, smooth stick with a hooked end that you pick up in the woods and trim to suit your needs. A more complicated development involved using a length of spun thread to tie a flattish, roundish stone together with a protruding stick, thus making a weight to drive the turning motion and a handle that could be used to start the stone spinning, as well as to wind the thread around as it was produced. 2 In time, this evolved into human-crafted spindle whorls and shafts, which give us Plato’s cosmic image, and the spindles of countless fairy tales.3

Spinners were imitating a divine process, and their work and their tools were always invested with symbolic meaning. The discovery of a spindle made of precious silver and gold in a Neolithic grave site in Anatolia, Turkey, demonstrates just how far back this symbolic, ritual significance extends. Meanwhile, the familiar stories of spindles and spinning that have come down to us often make clear that dangers and risks are involved in such an undertaking. If performed without reverence, it could lead to disaster.

In “Mother Holle,” for example, a story about two stepsisters, the industrious spinner reaps a golden reward, while the one who is too slothful to complete her task is punished with a hideous fate. This is more than a cautionary tale intended to frighten girls into fulfilling their societal roles, for as Jacob Grimm himself described in his Teutonic Mythology, Mother Holle is a manifestation of a Germanic nature-goddess, Hulda; it is said that snowflakes are the feathers shaken from her bed. When the girls fall into her world by tumbling into a well, they enter into the world behind nature, the world of the elemental forces that cause snow and rain, growth and fertility. Diligence in spinning is a sign that one is worthy of taking up that cosmic task, of becoming a co-creator with the divine. The alert awareness and feeling-sense required for good spinning are equated with compassion; the good sister answers an apple tree and an oven that call out to her for help, while the lazy one ignores them. Her failure dooms her to be covered with pitch, an outer sign of her inner insensibility.

Mechanization and materialization of the cosmic spinning activity can also lead to dire results, as shown in the tale of “Rumpelstiltskin.” In this story, the girl is a poor miller’s daughter, and the mill, like the spindle, is a wheel that resonates with the cosmic motion of the heavens. But rather than a simple tool for bringing order into chaos, it is a huge machine that crushes and pulverizes the living grain into a lifeless powder, rendering the miller poor indeed. To return life and value to this material, turning it into bread, would require a further step of transformation, of hard work and patience, but instead of humbly acknowledging this, the miller is moved by an impulse of worldly greed. He makes a wild claim that his daughter can spin straw into gold, and a grotesque trickster figure steps in to do it. Faced with her impossible task, unable to admit her inadequacy, the girl enters into a bargain with the subhuman creature.

When he claims her child as his reward, the girl, now a queen, has to earn back her life-giving power of transformation. And this time the way is through language, through naming. She must name the unknown and feared element in her life, must know it intimately, in order to overcome it.

It’s no accident that spinning is associated with language, that we speak of “spinning” a tale or telling a “yarn.” This, too, represents a step toward cosmic awareness, a human participation in the processes that create our destiny. When we look at events with such a higher awareness, we can perceive the links between them and come to a better understanding of their true essence. Spnning is rescued from falling into a mechanical search for material gain, and transformed into a quest for meaning and knowledge.

As anyone who has tried it knows, spinning is not a mindless task. It requires constant attention not to end up with a broken thread or a tangled mess. At the same time, the rhythmical balance of hand and mind working together is deeply satisfying and calming. The spinner may find her own thoughts changing, becoming organized along with the fiber, leading to new inspirations and insights. An inner “golden thread” can be sensed, one that connects us to the cosmic rhythms which created us.