The Coincidence of Meaning

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

—Excerpt from Burnt Norton (No. 1 of Four Quartets), T.S. Eliot

One evening, years ago, I wandered through a quiet New York City park, caught in the weight of a choice that felt impossibly large: whether to move across the country for a new chapter in my life. At the time, I was casually dating someone. We weren’t in a serious relationship, and we both knew a long-distance version probably wouldn’t endure—but the depth of our connection was undeniable.

Earlier that day, they had gone to the farmers market and brought me some plums, my favorite fruit. That simple gesture lingered with me as I moved beneath the bare branches, my thoughts a tangle of longing, fear, and possibility.

As I walked, I came upon a Little Free Library tucked beneath an old oak. On impulse, I opened it and pulled out a well-worn copy of The Norton Anthology of American Literature. I settled onto a nearby bench and began to flip through its pages. There, a familiar poem greeted me on a dog-eared page: William Carlos Williams’s “This Is Just to Say”:

I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox

and which you were probably saving for breakfast

Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold

My heart skipped. The coincidence was uncanny: the very fruit that had occupied my thoughts that morning, the gesture of affection I had cherished, mirrored in this text as if the universe had left me a quiet note. In that instant, something shifted. The nudge from the world felt intimate and deliberate, affirming that my choice need not be guided solely by ambition or practicality. I decided, then and there, not to move. My plum-giving partner and I are still together, years later, and every time I think of that evening, I feel the tender, uncanny touch of synchronicity—a reminder that sometimes the world conspires to meet us exactly where we are.

Moments like this echo the experiences Jung explored in his work on synchronicity, where meaningful coincidences reveal an intimate dialogue between inner and outer worlds. One of the most striking examples comes from his 1960 book Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle. A patient described a dream she had the night before, in which a golden scarab beetle appeared. As she spoke, Jung heard a gentle tapping at the window behind him. When he opened it, a real scarab beetle—remarkably similar to the one in the dream—flew into the room.

This “meaningful coincidence” collapsed the boundary between inner and outer experience, linking the patient’s psyche with the world in a way that defied ordinary causation. It broke through her intellectual resistance and confirmed the significance of their conversation. Moments like this compel a question at the heart of human experience: when inner and outer worlds collide, how do we make sense of it?

My William Carlos Williams story and Jung’s scarab beetle story both embody the essence of what Jung termed “synchronicity”: a “meaningful coincidence” without a discernible causal connection. It occupies a liminal zone between chance and fate—a “space of radical choice” where our will and passions determine our path, since the future is not predetermined (echoing William James’s philosophy of “genuine options”). This is the “explanatory gap,” a term from philosophy of mind introduced by Joseph Levine to describe the difficulty of explaining how physical processes give rise to subjective experience. Here, it marks the threshold where the outer world meets consciousness, and where meaning is neither imposed nor dictated, but discovered and shaped by our engagement. In this space, we are not mere observers; we are participants, free to ascribe significance in ways that resonate with consciousness and shape how we inhabit reality. Synchronicity is not just observed—it is co-created, a participatory phenomenon in which the boundaries between inner and outer, self and world, are fluid and responsive.

Encountering synchronicity is a moment of choice: do we see randomness or guidance? This decision is not merely intellectual; it is existential. As Kierkegaard suggests, it is through the exercise of choice and reflection on life’s events that we shape our existence and define our being (Either/Or, 1843). It is in this uniquely personal choice—deciding how to interpret the event—that we participate most fully in our own development, navigating the “fork in the road” presented by each synchronistic moment. In choosing how to engage with coincidence, we encounter a mirror that reflects both the outer world and the contours of our inner life. Synchronicity thus reveals not only the mysteries of the universe but also the architecture of our consciousness.

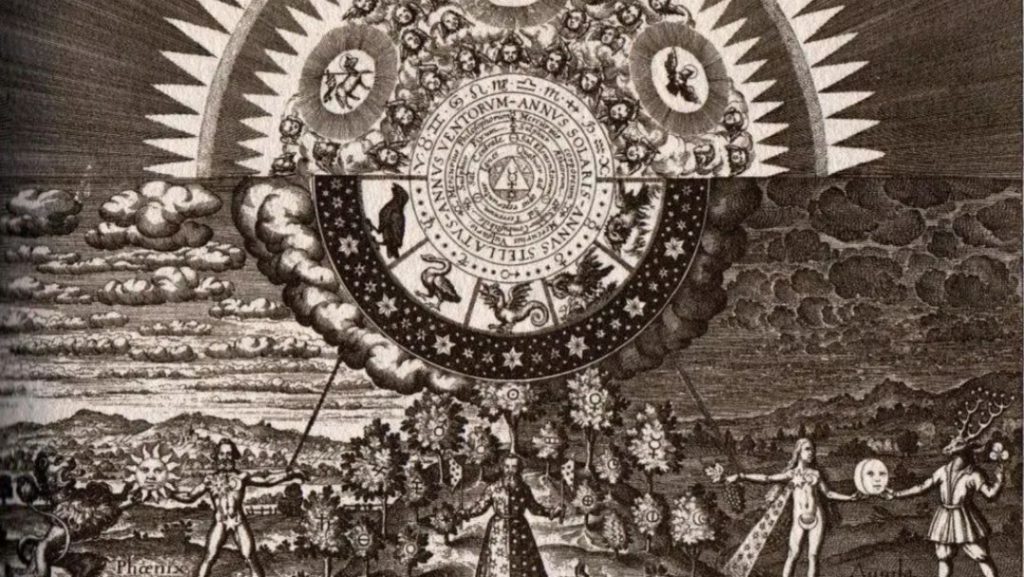

Beneath the apparent separateness of matter lies an “implicate order,” an underlying wholeness in which everything is enfolded and subtly interconnected, reflecting the outer world in the inner, as David Bohm suggested (Wholeness and the Implicate Order, 1980). Time, rather than unfolding linearly, is perceived most fully through intuition, revealing patterns invisible to analytical thought, according to Henri Bergson (Matter and Memory, 1896). Perception, Maurice Merleau-Ponty reminds us, is not passive; the world and the self co-create each other through every act of attention (Phenomenology of Perception, 1945). Even Einstein observed that distinctions between past, present, and future are not fixed, and his equation E=mc² shows that matter and energy are interchangeable, implying that reality itself is radiant—a “beam of light” in which all events resonate in subtle synchrony.

It is worth noting that, at the heart of the “beam of light,” synchronicities themselves would vanish. In this center of all reality, where mass and energy collapse into pure light, everything is already perfectly synchronized; there is no epistemic gap, no tension between inner and outer experience. Synchronicities emerge precisely because consciousness encounters the world as partially revealed, a space where meaning is not immediately apparent. At the core, where all is enfolded and aligned, the surprises and meaningful coincidences that define synchronicity are no longer necessary—the harmony is complete, and the dialogue between mind and cosmos becomes seamless. Perhaps noticing synchronicities more frequently is not superstition or mere pattern-seeking, but a sign that consciousness itself is more closely apprehending the central reality. As perception deepens, fragments of experience cohere, revealing the subtle order beneath apparent randomness.

The coherence glimpsed in synchronicity may also reflect Bohm’s deeper, underlying order. His “implicate order”—the “enfolded” whole in constant movement, or “holomovement”—proposes that every event in the observable world unfolds from an undivided, flowing reality. This resonates with T.S. Eliot’s “still point of the turning world” (Four Quartets, 1943), a calm fulcrum amid temporal flux, and with the mythic axis of Yggdrasil, connecting all realms. Synchronicities, then, are glimpses of this underlying wholeness, moments where inner and outer, mind and cosmos, enfold and resonate, revealing the hidden unity of existence.

Ultimately, the significance of synchronicity lies less in uncovering a definitive explanation than in acknowledging the interplay between mind and world. Whether we experience it as random, divinely guided, or something in between, these moments invite reflection, insight, and engagement with the unknown.

Like the golden scarab that flew through Jung’s window, they catch our attention, challenge our assumptions, and remind us that meaning is both discovered and created. By attending to them with curiosity and openness, we do more than witness coincidence—we participate in the ongoing story of our consciousness, finding resonance in the dialogue between inner and outer worlds.

Synchronicity is ever-present for those who are open to its resonance.

Return to the Table of Contents for Remembering the Future

Credit Line: An earlier version of this article appeared on Countercurrents. This article is licensed by the author under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)