Hafiz | Illuminating the Eternal Spirit of Love

Hafiz came on the scene during the Ilkhanate dynasty (established 1256, fifty-nine years before he was born). He was thirty-eight when it collapsed in 1353. Then, several dynasties (Injuids, Muzaffarids, Chobanids, Jalayirids, Kartids, etc.) gained power and declared independence, dividing Persia into smaller, regional states. Of these, Hafiz lived under the reign of the Injus and Muzaffarids. Persia was not united again until the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736) in the 16th century.

His dates are possibly 1315–1390 (716–791 AH), but this isn’t absolutely certain. (Please note, too: Muslims of his time didn’t celebrate birthdays.) It’s safe to say Hafiz was a contemporary of Chaucer. Yet Hafiz is more like Shakespeare, two centuries later. Both were immersed in cosmopolitan as well as local culture. Their affinity might even bear direct influence. Scholar Ernest Fenollosa points out that “the freedom of the Elizabethan mind, and its power to range over all planes of human experience, as in Shakespeare, was in part, an aftermath of Oriental contacts,” encounters with Iran included.

He was a native of Shiraz, the capital of the province of Fars, from which come the words Farsi and Persian. Throughout the Islamic world, for centuries, Shiraz had been considered as the House of Knowledge, comparable to the Athens of Iran. Situated for both land and maritime trade on the Silk Road and the Spice Routes, it was a major international trading center, and, as a regional political center, its economy was self-reliant. In Hafiz’s time, Shiraz was comparable to Florence under the de Medicis. Scholar Leonard Lewisohn describes it as home of “learned theologians, eloquent preachers, pious ascetics, ecstatic Sufis, erudite scholars, specialist theologians, great calligraphers, famous scientists, and adept men of letters.” Such a varied cultural and economic climate helped Shiraz survive intense periods of political violence. Within that background of artistic and intellectual brilliance, Hafiz’s grasp of the philosophies, poetics, and politics of his time provided solid, rich grounding for him to reach beyond any other Persian poet, before or after[1]. Indeed, Hafiz is considered the zenith, the acme, the pinnacle, the apex of classical Persian literature of all time. In his lifetime, his lyrics captivated the soul of his people. His latest ones would be copied by hand and distributed for minstrels to sing and for people to read after performances. While written words were slower to travel, song was immediate. So his audience in his lifetime extended across Iran, from Fars to Khorasan and Azerbaijan. And, attesting to the reach of extending beyond national borders, his devotees could be found in such Persianate communities as India, Turkistan, and Mesopotamia.

Someone suggested he gather his lyrics together – following the common Persian practice of collecting and publishing a poet’s works into a book (divan) in his or her lifetime. But, no. His gears seemed to know no reverse, except to further refine and polish his work. His refusal to commit to a divan meant his work remained to be collected and arranged by others, beginning a dozen years after his death. His poems weren’t dated, although some clearly refer to contemporary events. But divans weren’t typically arranged chronologically nor even thematically but, rather, by the syllables rhyming at the ends of lines. What’s important to note here is that Hafiz’s divan, some five hundred lyric poems, is half or a third less than his peers. This reflects his “soul-digging, hardworking” commitment to craft, seen in each lyric’s high degree of polish.

Today, you’re likely to find two books in homes in Iran, a Qur’an and Hafiz’s divan. Sometimes the latter is more dog-eared than the former – as people commonly memorize his poetry, and quote lines to each other.

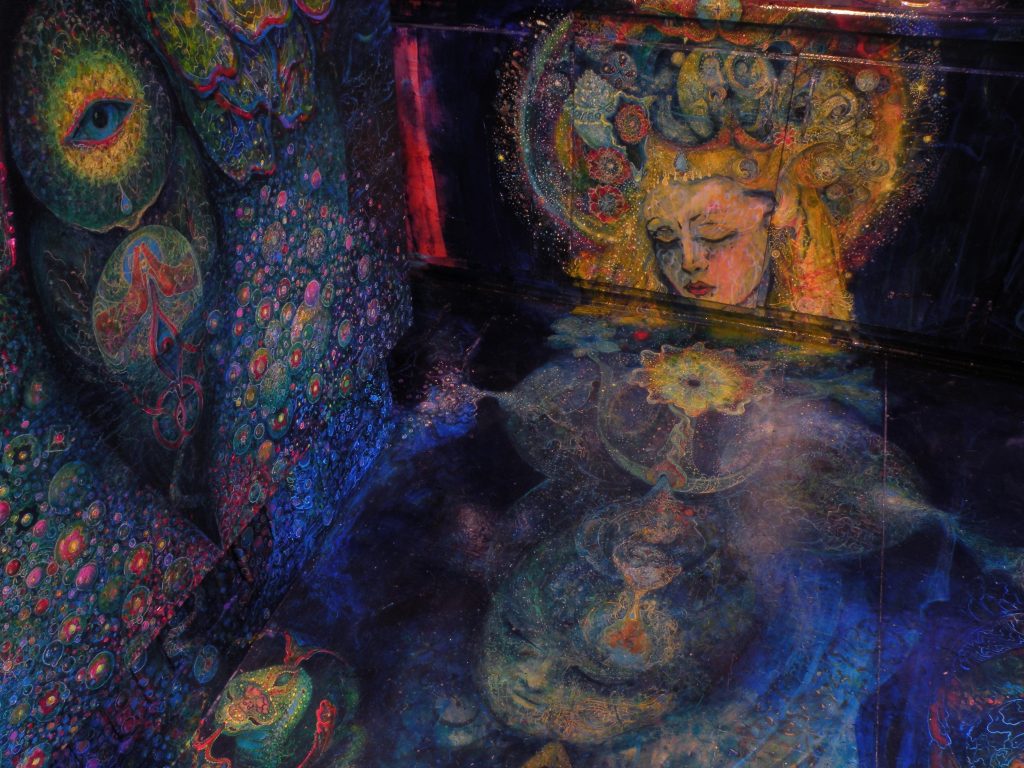

Hafiz was deeply influenced by Sufism, a mystical branch of Islam. His poetry reflects Sufi themes of divine love, spiritual awakening, and the quest for union with the Divine. Islam is the second largest and fastest growing religion in the world, within which Sufism is sometimes considered “the other Islam.”

Sufism is believed to be both a historical reality that appeared in the Muslim world after the advent of Islam as well as a “reality without a name,” a trans-historical phenomenon that has been present from the time that the first human experienced a sense of separateness from and at- traction to ultimate reality. – Alan Godlas

Much of what the West knows about Sufism is initially through poets – Rumi, Attar, Sa’di, and Hafez, for example. This influence can be seen as early as the 12 th century, in minstrels and jongleurs, courtly trouvères and troubadours, and Dante – later in Goethe & Emerson. A leading Sufic trait is the dialogue of the sacred and the secular, through love poems, where the mortal and the divine Beloved are interfused, mirroring and magnifying each other;

A lyric poet and a mystic poet, Hafiz is also an ecstatic poet. Singing of pain and of joy, Hafiz also touches something beyond either. A member of the school of Islamic philosopher Abu Hamid al-Ghazali once said, “For his lovers, God pours out a draft from the cup of His love, and by that draft they are intoxicated, rapt away from themselves.” In this rapturous vintage, we can taste the Greek roots of ecstasy: going beyond self. Dissatisfaction with the world, the inebriation of wine, the surprise and transport of love, and recognition of the value of methods of living in harmony and joy – each are points of departure from the illusory view of the limited, isolated self (“the skin-encapsulated ego”), into a realm of silent ecstasy.. ) But, enough prose! It’s time to saddle up the camels and journey to … Hafiz.

following are vignettes from whole poems, based on adaptations by filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami

Gertrude Bell’s Classic Translations of Hafiz

Gertrude Bell, a remarkable British archaeologist, traveler, and diplomat of the early 20th century, is renowned for her extensive contributions to Middle Eastern history and culture. Among her notable works, she is celebrated for her classic translations of the enchanting poetry of Hafiz, which played a vital role in introducing the Western world to the profound beauty and spiritual depth of Persian literature.

From The Garden of Heaven

FROM the garden of Heaven a western breeze

Blows through the leaves of my garden of earth;

With a love like a huri I’ld take mine ease,

And wine! bring me wine, the giver of mirth!

To-day the beggar may boast him a king,

His banqueting-hall is the ripening field,

And his tent the shadow that soft clouds fling.

A tale of April the meadows unfold–

Ah, foolish for future credit to slave,

And to leave the cash of the present untold!

Build a fort with wine where thy heart may brave

The assault of the world; when thy fortress falls,

The relentless victor shall knead from thy dust

The bricks that repair its crumbling walls.

Trust not the word of that foe in the fight!

Shall the lamp of the synagogue lend its flame

To set thy monastic torches alight?

Drunken am I, yet place not my name

In the Book of Doom, nor pass judgment on it;

Who knows what the secret finger of Fate

Upon his own white forehead has writ!

And when the spirit of Hafiz has fled,

Follow his bier with a tribute of sighs;

Though the ocean of sin has closed o’er his head,

He may find a place in God’s Paradise.

See more translations by Gertrude Bell at Poet Seers

I asked the sage “When did the All-Wise

make you a seer?”

“ Same day, “ he said,

“As the great Azure Dome was made”

No surprise

If in Seventh Heaven

Lyrics composed by Hafiz

& sung by Venus

Entice

Jesus to dance

At the time of Adam

In the Garden of Paradise

The poetry of Hafiz

Ornamented the diaries

Of the wild lilacs & the amaryllis

Be in harmony

With the spring clouds

Commemorate

The ones who are gone

&

Those who love

Every moment

With you

I’m falling in love

Anew

Adapted, and reprinted with permission from Hampton Roads Publishing, Hafiz’s Little Book of Life translated by Erfan Mojib and Gary Gach is available wherever books and ebooks are sold or directly from the publisher at www.redwheelweiser.com Paperback | Audio Edition, read by Samara Naeymi

[1]

His dates place him a century after Rumi. Where Rumi wrote of one lifelong theme, Hafiz’s vast scope make him all the more universal, and deserving of no less attention. As scholar Omid Safi has put it, if Rumi is a tumultuous ocean of love, Hafiz is an illuminated and many-faceted diamond.