Vision for a City of Hope Near Auschwitz

Vision for a City of Hope Near Auschwitz

From a quiet meadow in Cambodia to the twin fountains of Manhattan, humanity’s worst moments have left scars across our landscapes and our psyches. They appear in the shape of long concrete slabs in Kigali, Rwanda, or a crooked, skeletonized dome atop Hiroshima. Reminders of past tragedies, they remain in a constant state of slow and imperceptible healing throughout history.

The Holocaust is undoubtedly the largest and longest scar in modern Western history. You can trace it as one would trace a railroad track in a desolate field, leading, inevitably, through the brick archway of Auschwitz. Since liberation and the subsequent forming of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in 1947, the public has willingly entered such archways. Now a UN World Heritage site, an annual 2 million people from all walks of life across the world come to mourn, find names, to see and feel and know what was once the world’s darkest secret.

I first visited Auschwitz in 2015. This came at a time when I was slowing down Children of the Earth, a UN NGO that I founded and directed for over 30 years that worked and reached into 90 countries. Never did I imagine that I would have anything to do with Auschwitz.

I was invited there by a small group of women who were doing a project in Berlin based on their work in peace and sustainability. Walking through the camp, I came to the large Book of Names: a list of every murdered prisoner. Browsing through the list, I discovered not only my maternal grandmother’s name but 20 other family members who also had been murdered. During my life, I have traveled to various war-torn countries. I’ve encountered all manner of suffering and misery, but seeing these names haunted me to the core. I knew then that part of my legacy would need to include future projects to honor those 20 names (and millions of others), and also make a difference for the world’s future generations. After meeting Domen Kocevar, a social activist with a background in theology and sociology, I realized that Auschwitz was the impact point for the final landing site that fused all of my previous work. It was then that Domen fostered the idea of One Humanity.

Science and spirituality have come to the same conclusion: all people are intrinsically similar; the human genome project has proven that we are genetically 99.9 percent alike, with only one tenth of one percent that makes us different. When we realize that “I am you and you are me,” only then will right action and thought be supported by the universal laws of nature. When we can concentrate on what makes us the same instead of what makes us different, only then can we deal with the challenges ahead. The overarching goal for this vision is to lay the groundwork for global solidarity that gives rise to what it means to be One Humanity.

There needs to be a housing for all of these ideas, something concrete and anchored in the real world. A physical place that manifests the theoretical, where ideas become actions. The need is clear for a One Humanity Institute.

The One Humanity Institute (OHI) is a nonprofit charitable foundation co-founded in 2017 by me and Domen. It embraces peace that goes beyond the mere absence of conflict and war, to bring about a change of heart that embraces our common humanity. Peace in this sense is a dynamic concept that facilitates the full development of the human potential. Our intention is to create a transformative campus for mutual cultural understanding next to Auschwitz, named “City of Hope,” which provides a visionary, experiential, and tangible place to actualize this vision.

City of Hope will offer structured learning opportunities in a variety of forms for all ages, through both formal and non-formal education. Such opportunities will focus on the UN 17 Sustainable Development Goals, conflict resolution, responsible stewardship of our planet, and the promotion of religious and spiritual pluralism. By promoting new methods of governance, innovative finance, and transformative education systems, OHI aspires to encourage a new narrative for humanity that not only honors the sacredness of every human, but proposes new approaches and new systems to nurture this into reality.

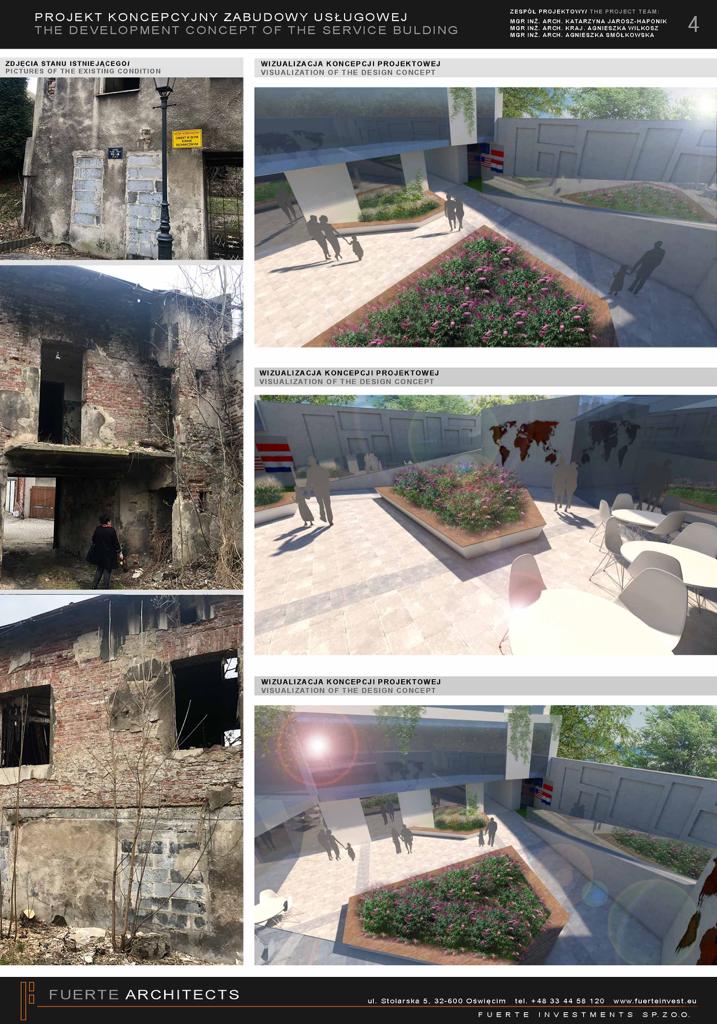

The size and scope of the project have expanded remarkably from its humble beginning: a park bench. Domen and I first wanted to address the need at Auschwitz for a quiet place of reflection after touring the camp—a space that could allow the impact of Auschwitz to become a lesson in itself for needing change. Then we considered the idea of a student exchange program with a local school as an avenue of furthering multicultural and interreligious understanding. These small projects only fed our desire to expand the concept of OHI, and as our aspirations grew, so did the roadblocks in our way. But as one door closed, another opened.

The project, as it stands today, was made possible by one fateful, fortuitous event—the day we learned about the 11 unused barracks adjacent to the Auschwitz Museum. These structures originally were occupied by the German army during the war. Now they sit dormant. Our plan is to purchase the land that houses these barracks, then transform the unique and symbolic space into a City of Hope. The area will contain an NGO hub, library, EnVisionarium, learning and research center, peace gardens, and hotel.

The EnVisionarium is an interactive, innovative museum of the future, designed to integrate the understanding of sustainability with that of human connectedness. Visitors will be exposed to revolving exhibits, innovative experiences, and living, experiential structures for mind-shifting. Guests will access practical tools: innovative, state-of-the-art, and virtual models that provide breakthroughs for resolving both personal and global issues.

The OHI Learning and Research Center provides transformative learning programs and experiences in peace and sustainability for all ages that foster a structural shift in human interconnectedness. It will involve a global community of scholars and practitioners from diverse backgrounds to address urgent social, political, and ecological problems. With official ties to renowned universities around the world, the Center will host courses, global youth exchanges, workshops, training programs, think tank meetings, and more. The Center also will contain a digital Peace Library.

The OHI Hub focuses on a number of issues, including entrepreneurship, social innovations, and 21st-century technology, particularly for youth. By providing shared offices and working space for NGOs, the OHI Hub will provide an environment for unprecedented, unified, and collective impact. The Hub also will offer space to organizations that share common values as a means to cross-pollinate skills and expertise.

Upon the advice of numerous well-informed Polish citizens and leaders, we made an investigative trip to Israel to learn more about its perspective. While there, we met a second-generation Jewish survivor whose family had lived in their bakery in the old city center in Oswiecim. He has donated his family home to OHI in order to connect the past with the present, and to create a better future. This building, once renovated, will be our headquarters and a pilot prototype. Not only will the home serve as a bakery as it did 80 years ago, but it will provide co-working space for youth and other social innovators, local organizations similar to OHI, and volunteers. It will be known as Bakery2030 (Piekarnia2030), a reference to the year on which the UN Sustainable Development Goals are to be accomplished.

Since 2015, Domen and I have had many visits to the town of Oswiecim, as well as meetings with the town governor, mayor of the city, and representatives of local NGOs and educational institutions. We also have engaged 40 experts to work with us—a diverse group of thought-leaders, change agents, and individuals from across the globe with vast experience and broad backgrounds. We currently are forming a global Youth Council of formidable young leaders.

By learning from the lessons of the past, we can create bridges to a future of One Humanity values. After five years of this work, I realize the enormity of the OHI vision and undertaking. The present world needs a recalibration to create a better future. It is now necessary for our survival as a species to go beyond personal greed and the false separation of identities fostered by religions, genders, cultures, and ethnic groups. Our lives are hanging on a shoestring, floundering. Many from the generations to follow already recognize these ills. They need us to be a bridge in order to understand that we must experience ourselves as one humanity. Only together can we resolve the global issues we face. We are walking into a state of emergency where “Never Again” seems distant in the past, yet more than ever we need this phrase as an essential reminder. OHI is more than a project; it is a call to make visible the possibilities of how we may live together in a positive manner that serves humanity as a whole.

The time has come for us to commit to stewarding a better future—one that works for everyone. A world of One Humanity. We have bold goals for OHI, indeed, but the feedback we are getting across the globe tells us that our idea is one whose time has come.

Re-member Humanity.

About Nina Meyerhof

As President and Founder of Children of the Earth, Nina Meyerhof has made a life of advocating for children and youth. As her vocation, she served as the special education coordinator for a ten-school district in southern Vermont. Dr. Meyerhof has extensive background in the needs of all children, with Master of Arts degrees in both Special Education and in Counseling, and a Certificate of Advanced Graduate Studies in Psychology.

She also holds a doctorate in Educational Policy, Research, and Administration from the University of Massachusetts, where she developed a self-esteem model to be used in schools.

Gaza on My Mind

Gaza on My Mind

Talking about Gaza can be scary. I have expressed my horror about the savage Hamas attack on Israelis, and the heartbreaking plight of the hostages, but when I criticize Israeli policies and the bombing of Gaza, some of my Jewish friends have called me antisemitic. This is hurtful. To say this is a controversial subject is an understatement. I am not a scholar or historian. I am not Muslim or Jewish. So why do I feel compelled to discuss this?

Though I do not identify with any organized religion, I do identify as an American. Not the nationalistic “my country right or wrong” American, but rather a Langston Hughes style American who sees our country as “the land that never has been yet — and yet must be — a land where every man is free.” I am ashamed of American’s sordid history – the genocide of Native Americans, the slavery of Africans, the unjust treatment of African Americans since emancipation, and other ongoing violations of our principles. l am an American who, like the poet Hughes, has sworn that someday America will be the country where our ideals of liberty and justice for all people will be achieved. It is vital to me that US foreign policy confirms and reflects these ideals. As I once opposed the bombing of the Vietnamese and then the Iraqis, I now oppose the US financed bombing of Gaza and uphold the right of Palestinians to self-determination.

This article explains how I came to oppose US military support of Israel’s war on Gaza, as well as its occupation of the Palestinian territories. My story begins twenty years ago, in September 2003, when I traveled to Gaza to honor the life and death of a twenty-three-year-old American peace activist named Rachel Corrie. She was a volunteer human rights observer with the International Solidarity Movement, a pro-Palestinian group founded by Israeli and Palestinian activists, who were committed to resisting the Israeli occupation by using Gandhian nonviolent practices and protest. When I learned that Rachel had been crushed to death on March 16, 2003, by an Israeli-owned bulldozer as she stood before the home of a Palestinian physician and his family to defend it from demolition, I felt compelled to go there and to understand why.

I called my activist friend Medea Benjamin, co-founder of Global Exchange and Code Pink, to ask if she would come with me to Gaza. Though she had been avoiding involvement in the conflict in deference to her Jewish parents, Medea was now ready to go. I recruited a delegation of seven women, including two Jewish and one Muslim, and Global Exchange organized our itinerary to meet with Israeli and Palestinian human rights groups in Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank.

The purpose of our 2003 trip was to gain insight into the conflict between Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories. My mission was also to establish relationships with a Jewish-owned restaurant in Israel and an Arab-owned restaurant in the occupied Palestinian territories as part of the White Dog Cafe’s International Sister Restaurant program, “Table for Five Billion.” Beginning in 1987 the program had brought delegations of our customers and staff to Nicaragua, Cuba, Vietnam, and the Soviet Union to experience the impact of US foreign policy and work toward a world where everyone (five billion then, and even more now) has a place at the table.

When we arrived in Gaza in September of 2003, our group of travelers sat sipping coffee in a busy outdoor café, much like any European café, in Gaza City. When we heard the hum of an airplane in the distance, I saw alarm on the faces of our Palestinian hosts. On the way to the café, we had seen the burned- out carcass of a car blocking a narrow street in a busy marketplace and been told that it had been hit by an Israeli Defense Force (IDF) missile, killing many innocent bystanders. Even in this peaceful café setting, I saw how people lived in fear in Gaza — called by many “an open-air prison,” from which there was little escape.

Twenty years later, fear has consumed all of Gaza night and day as Israeli fighters unleash the most destructive bombing campaign in modern history, already having used more than twice the firepower of the nuclear bomb dropped on Hiroshima. As many as 27,000 Palestinians have been killed, including more than 12,000 children and 66,000 wounded. No hospitals are fully functional. There is no anesthesia for surgeries. No antibiotics to stave of deadly infections. Families and orphans of those killed are sleeping in tents and on the street. One toilet is available for every 500 people, according to the World Health Organization. Since October 7, over 400 doctors and medical staff have been killed. The UN has lost 142 personnel, the largest number lost in any conflict in history. More than one hundred and twenty journalists have been killed, and the International Federation of Journalists in NYC has accused the IDF of ‘deliberately targeting’ media professionals working in Gaza

One of the most moving experiences for me on our 2003 trip was meeting Rami Elhannan, an Israeli whose 14-year-old daughter had been killed by a Hamas suicide bomber on her way home from school in 1997. After a year of struggling with anger and despair, Rami joined Bereaved Families Supporting Reconciliation and Peace, a group of Israeli and Palestinian families who had each lost loved ones to the conflict. He told us that his life had taken on new meaning as he worked in partnership with Palestinians to stop violence and end the occupation.

Now twenty years later, Hamas has only gained in strength. Their murderous attack on October 7, killing 1200 Israelis and taking 250 hostages is the tragic result of what they have become. What gives me hope is that Rami, even after this outrage, continues his work to end the violence and co-exist peacefully with Palestinians. The reconciliation and peace organization, now called Parents Circle, is co-directed by Rami and his Palestinian counterpart, Bassam Aramin, whose 10-year-old daughter was killed in 2007 by an IDF soldier using a US issued M-16 rifle, as she stood outside of her school.

In a 2023 interview, Rami explained that twenty-five years ago, he had never seen a Palestinian as a human being. But through the Parents Circle he had learned the music, the culture, and the stories of the Palestinians, which he explained had been deliberately hidden from him by the Israeli education system. When asked how to end the conflict, Rami said that the most important word is “respect” and to see Palestinians as equal partners in building a peaceful future.

In 2003, when we arrived in Rafah, a Palestinian city in the southernmost part of Gaza, near the Israeli-controlled border with Egypt, we visited the home of a Palestinian school headmaster Khalil Bashir. We were horrified to find that Israeli soldiers had not only destroyed his groves of date and olive trees and two acres of greenhouses, but the soldiers had also taken over the upper floors of his three-story home as an army base to protect the newly erected homes of Israeli settlers nearby. Despite this unimaginable disrespect, Khalil continued to teach non-violence and peaceful coexistence to his children and students.

In a letter to her mother in February 2003, Rachel Corrie wrote about the people of Gaza:

“I am amazed at their strength in being able to defend such a large degree of their humanity – laughter, generosity, family-time – against the incredible horror occurring in their lives and against the constant presence of death. I am also discovering a degree of strength and of basic ability for humans to remain human in the direst of circumstances. I think the word is dignity.”

We later learned that in 2004 Khalil’s 15-year-old son, Yousef Bashir, had been shot in the back by an IDF soldier. Because three UN officials witnessed this, he was sent to an Israeli hospital where he slowly recovered. Since then, Yousef moved to the US and wrote a book about his father’s dedication to non-violence. In a 2019 New York Times op-ed, he said this about the soldier who shot him: “I wish we could talk. I would tell him that I want to do my part to make peace between our peoples more possible, the way my father taught me. I would tell him that I have forgiven him.”In Rafah, our delegation next went to the place where Rachael Corrie was killed. We stood solemnly before the pile of rubble that marked where she had been crushed under an armored bulldozer driven by an IDF soldier. Prior to her death, over six hundred houses had been destroyed in Rafah, along with Palestinian businesses, including 25 greenhouses, the source of income for three hundred people. In her last email to her father written less than two weeks before her death, 23-year-old Rachel wrote:

“Coming here is one of the better things I’ve ever done. So when I sound crazy, or if the Israeli military should break with their racist tendency not to injure white people, please pin the reason squarely on the fact that I am in the midst of a genocide which I am also indirectly supporting, and for which my government is largely responsible.”

I understand that some readers who identify with Israel may not agree with Rachel’s analysis of the situation, but it’s important to know how she saw it and to admire her willingness to stand up to the powerful forces she viewed as oppressors, as we hope someone would do for us and our families if we were in such danger. Twenty years later, in 2023, I still picture the pile of rubble marking the spot where Rachel tragically lost her life amid the destruction of Palestinian homes and businesses. I am deeply saddened to know that today the rubble has grown to encompass much of Gaza, with over 70% of housing demolished by Israeli bombs, displacing 90% of the population. Untold thousands of Palestinian civilians in Gaza, over a third children and infants, have been crushed to death in their own homes.

In 2003, we saw so many Palestinian children, often dressed in neat school uniforms, their eyes bright and faces curious to meet strangers. They pointed out the bullet holes in their houses and showed us shell casings they had collected during the IDF incursions, and they pointed to the place where Tom Hurtnell, a young English volunteer, was shot in the head as he ran to grab a child who was caught in gunfire. In Hebron, a Palestinian town in the West Bank where four hundred Jewish settlers from Russia had illegally taken residence, we met with Chris Brown from Christian Peacekeepers Team. He explained how his group escorted children to school through army barricades, where the IDF soldiers point guns at them, and past hostile settlers who hurl abuse, and sometimes spit on and physically attack the children. By 2003, over six hundred Palestinian children had died in the conflict at the hands of the IDF or the settlers. We visited a school where the children sang to welcome us, and as we looked at their promising young faces, it was hard not to despair over the sheer hopelessness of their future.

Palestinian school children passing through an IDF checkpoint on their way to school, Hebron, West Bank, 2003.

Palestinian school children passing through an IDF checkpoint on their way to school, Hebron, West Bank, 2003. I never imagined that twenty years later, against international law, there would be over 700,000 settlers in the West Bank and East Jerusalem occupying 40% of Palestinian land against international law. Just since October, 739 Palestinians in the West Bank, including 309 children, have been displaced, following the destruction of 115 homes. The IDF has armed settlers in the West Bank, giving them impunity to violently force Palestinians from their homes, increasing acts of violence from an average of three a day to seven. Recently, a Palestinian-American teenager visiting his cousins was shot in the head. He is one of 369 killed in the West Bank since October, including ninety-five children.As our 2003 delegation traveled through the West Bank, we saw how the yards of the settlers’ homes were lush and green with well-watered grass, in sharp contrast to the arid, brown, and lifeless Palestinian areas. At a large Jewish settlement near Jerusalem, we even saw people enjoying an Olympic size swimming pool, while the Palestinians were forced to survive on 20% of the available water, even though their population is far greater, and did not have enough water to grow their crops to feed their people.

Though this seemed so unfair back in 2003, it would have been unimaginable to think that, in response to the Hamas attack on October 7, the Israelis would cut off ALL water supply to the entire population of Gaza, as well as all food, fuel and medical supplies, leaving Palestinians to die of starvation, dehydration, and disease. Over 70% of the population is drinking contaminated or salty water, according to the UN. Recently, the World Food Program reported, “In Gaza at this moment, literally the whole population is in crisis level of hunger or worse. And of those people, about 26%, meaning one-quarter of the population is literally starving – about 577,000 people.” According to the UN, famine is now “inevitable” following the news that the US and some other Western countries have suspended funding to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA) because Israel has accused 12 of its 13,000 employees to have been involved in the October 7 attack. Though nine of the accused have been fired, one has died, and two are under investigation, funding needed to combat the famine that endangers millions of Palestinians has been denied.While our delegation was in Tel Aviv, we told a group of Israeli youth that we were staying with a Palestinian family. Their eyes widened with fear and surprise, as they warned us that we would be raped and murdered because Palestinians were dangerous terrorists. Though I heard Israelis claim that Palestinian youth are taught to hate Jews, this experience made me wonder if Israeli youth had been taught that all Palestinians are terrorists.

When I watched the 2023 film Israelism, produced by courageous young Jewish filmmakers, I finally understood the racist remarks of the Israeli youth we had met 20 years before. According to the documentary, Israeli students, as well as visiting American students, are subject to racist and militaristic indoctrination that teaches them to fear, loathe, and dehumanize Palestinians. On both sides, it is hatred of “the other” that underlies and inflames the conflict.

The Israeli policy of demolishing homes had led to Rachel’s death, and so in 2003 we met with Angela Godfrey-Goldstein from the Israeli Committee Against Home Demolition, where we learned how the IDF was, in violation of international law, demolishing Palestinian homes, their means of income and their cultural institutions, and replacing them with Jewish settlements. One of the most surprising and horrifying parts of our 2023 trip was seeing the frequent IDF checkpoints on roadways where Palestinians were stopped, searched, delayed, and humiliated while waiting for hours in the hot sun or rain. As a result, travel that should take minutes takes hours and even days, separating people from their jobs, schools, friends, and family. An Israeli peace group, Bat Shalom, told us that over sixty Palestinian newborns, unable to get to the hospital, had died at checkpoints. In contrast, modern highways connecting Jewish settlements were “Jews Only,” which reminded me of the “Whites Only” drinking fountains I had been shocked to see as a young girl visiting the US South.

Lately, I have been hearing the term “settler colonialism” in relation to the war in Gaza. I was not exactly sure what it meant, so I checked back in with the Israeli Committee Against Home Demolition and read an October 2023 article by its founder, American Israeli Jeff Halper. In reading this article, I came to understand why Rachel and many thousands of Palestinians have been tragically killed. As I write, the rightwing leadership in Israel is publicly advocating for the permanent displacement of Palestinians and the building of Jewish settlements in Gaza. For me, Halper’s description of “settler colonialism” rings true to what I have witnessed in Palestine, and to what happened in the founding of the US. I want to believe that, lost in our own shameful colonial past, there may have been non-violent settlers in the US who sought peaceful coexistence with the Native Americans, and stood up courageously as Rachel did. Halper wrote:

“Settler colonialism is a deliberate, structured, and prolonged process in which one people not only takes over the country of another – violently by necessity – but seeks to transform it from what it was at the time of invasion into an entirely new entity, a new country reflecting the settlers’ presence, entirely erasing the natives’ presence and history. It is not a “conflict”. There are no “sides”, no symmetry of “violence”. The settler project is a unilateral one which must deny the indigenous population’s existence as a people endowed with rights to their land and identities if it is to claim the country exclusively for itself. Following from that is the need to move the indigenous off their land, killing them, driving them out of the country or confining them to tiny enclaves, so as to settle the land with the settler population itself. Then comes the process of erasure: erasing the physical and cultural presence of the indigenous from the landscape and replacing it with the settlers’ own manufactured history, heritage, national narrative and national identity. After a prolonged process of violent displacement and the pacification of those amongst the indigenous who remain, the settler project concludes quietly. Now the world is presented with a normal, peace-loving, democratic country remade in the settler’s image, and the settler colony fosters a popular perception that it is the “real” country. (Try buying a plane ticket to Palestine.) The process of normalization is complete; any further resistance on the part of the native population is criminalized as “terrorism” and, as such, is effectively de-politicized and delegitimized.”

On February 15, 2003, a month before Rachel Corrie’s death, 25 million people in over 100 countries around the world took to the streets saying NO to George Bush’s war in Iraq. It was the largest peace demonstration in world history. On February 28, Rachel wrote:

“I look forward to more moments like February 15 when civil society wakes up en masse and issues massive and resonant evidence of its conscience, it’s unwillingness to be repressed, and it’s compassion for the suffering of others.”

Twenty years later, as Rachel Corrie hoped, global consciousness is growing. Millions of people around the world are holding massive demonstrations — in London, Tokyo, New York, Rome, Athens, Sydney, Jakarta, Istanbul, Bangkok, Sao Paulo, Bucharest, Paris, Berlin, and Johannesburg — calling for a ceasefire and the liberation of the long oppressed Palestinian people. Many of these protests are organized by Jewish organizations who stand squarely for peace and human rights for all. Israelis, in partnership with Palestinians, have formed groups such as A Land for All and Standing Together and are working on plans for a future of peaceful coexistence in two neighboring states. The current crisis makes them even more determined to achieve their vision.

Having gained the world’s attention, could the tragedy of Gaza possibly provide the opportunity for a turning point in human civilization when the people of the world give birth to a new world order built on the idea that we are all one, with no them and us, and that war is obsolete? On February 28, just a couple weeks before her death, Rachel wrote to her mother:

“I think I could see a Palestinian state or a democratic Israeli-Palestinian state within my lifetime. I think freedom for Palestine could be an incredible source of hope to people struggling all over the world. I think it could also be an incredible inspiration to Arab people in the Middle East, who are struggling under undemocratic regimes, which the US supports. I look forward to increasing numbers of middle-class privileged people like you and me becoming aware of these structures that support our privilege and beginning to support the work of those who aren’t privileged to dismantle those structures.”

In 1995, White Dog Café began holding a Freedom Seder, a celebration of the exodus of the Jewish people from bondage as slaves in Egypt, which we continued every Passover, until I retired and sold the business in 2009. A rabbi would preside, and each year we created a booklet, a Haggadah, to accompany the service, tell the story, and share the ‘ten plagues’ of our time. Often a member of another community that was fighting oppression would also speak. Our purpose was to spread the Jewish message of freedom from oppression for all people — that all people are created in the image of God and deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.

I can understand that for many Jews the actions of the Israeli government are at odds with what they believe are at the heart of Judaism and its wise teachings —hence the protest signs, “Not in My Name.” Young American Jews, who have organized to reclaim Judaism in the spirit of seeing God in all people, embody Rachel’s dream for peace and justice:

Jewish Voice for Peace says, “We imagine Jewish Israelis joining Palestinians to build a just society, rooted in equality rather than supremacy, dignity rather than domination, democracy rather than dispossession. A society where every life is precious.”

If Not Now, a movement led by young Jews, says, “We call on our community to imagine a future beyond “us or them” — where Israelis and Palestinians are both safe: A future of equality, where everyone from the river to the sea has individual and collective rights to safety, the resources they need to live, freedom of movement, and political representation.”

My hope for peace in Israel and Palestine, and for a world where everyone has a place at the table, lies largely with these young people who stand as beacons of light in the darkness. As was Rachel, they are courageous to oppose racism and militarism and call for Israel to be a model of coexistence that the world so desperately needs. If not now, when?

Judy and the delegation of American women joined 200 Palestinian women and 250 Israeli women on September 6, 2003, in Talkarem, West Bank, to protest the Apartheid Wall that separated the villagers from 7000 acres of their agricultural land and 26 wells. The Israeli women brought school supplies to the gate as a gift to the Palestinians. The IDF teargassed those of us on the Palestinian side of the wall. Photographer unknown.

Judy and the delegation of American women joined 200 Palestinian women and 250 Israeli women on September 6, 2003, in Talkarem, West Bank, to protest the Apartheid Wall that separated the villagers from 7000 acres of their agricultural land and 26 wells. The Israeli women brought school supplies to the gate as a gift to the Palestinians. The IDF teargassed those of us on the Palestinian side of the wall. Photographer unknown.

Return to Strength in Openness Contents Page

About Judy Wicks

I’m a retired entrepreneur, activist and author working for peace, human rights, and the well-being of all species.

My life-long work has focused on building just and restorative regional economies as an alternative to extractive, profit-driven corporate globalization. Local economies lower the carbons of long distance shipping, create greater equality through decentralized ownership, lower dependance on vulnerable global supply chains, and prepare future generations to survive climate chaos by producing basic needs as close to home as possible.

Now retired from business and organizational work, I am focused on building a sustainable, solar-run 2-acre homestead in Philadelphia, where my daughter and I have turned a lawn into a meadow, orchard and vegetable garden.

I continue to support under-resourced, local entrepreneurs who are helping to build our regional economy.

Currently, my activism is aimed at a ceasefire in Gaza and self-determination for Palestinians.

For more, visit www.judywicks.com.

The Teachings in a Time of Intense World Crisis

The Teachings in a Time of Intense World Crisis

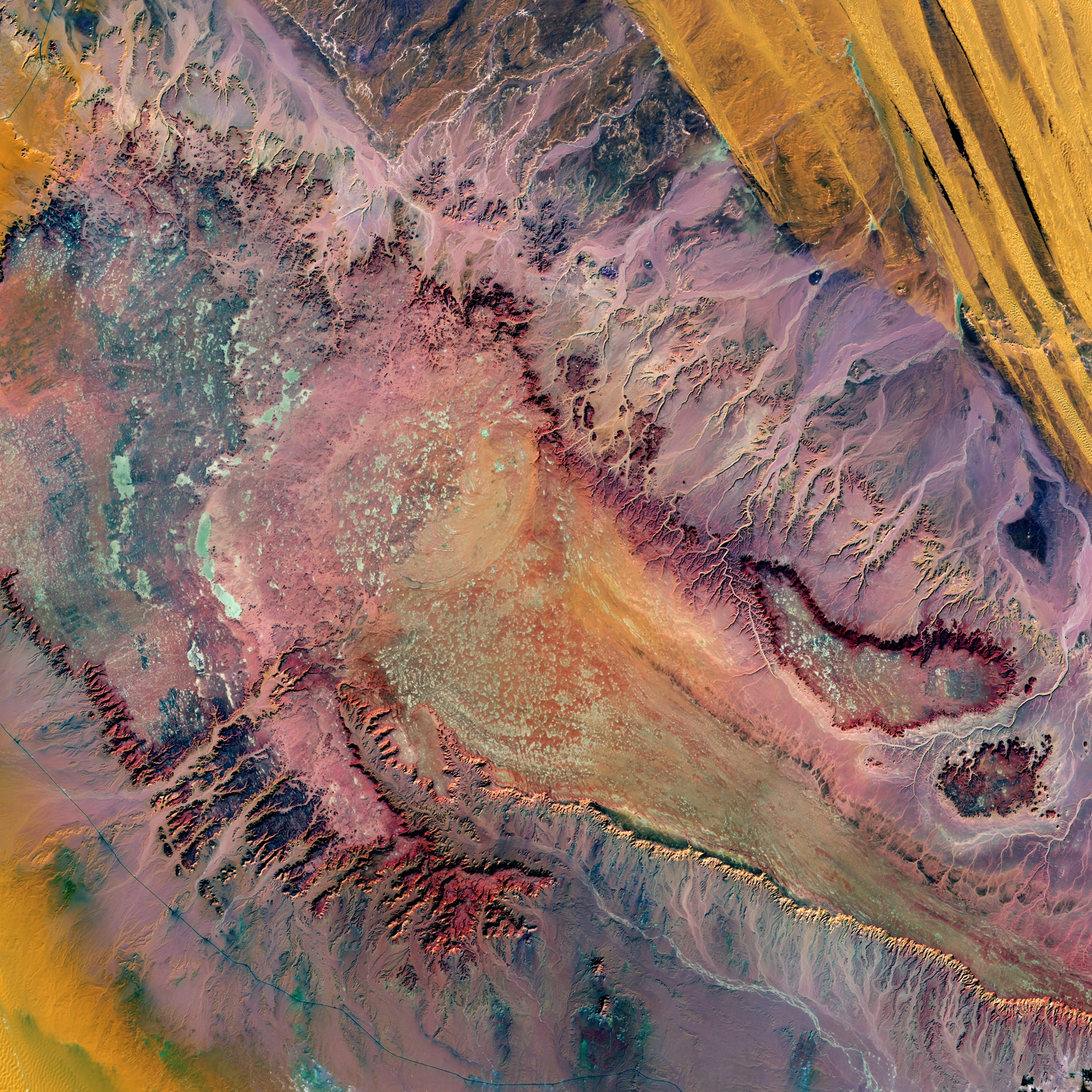

Cover image | Meandering wadis combine to form dense, branching networks across the stark, arid landscape of southeastern Jordan.

How interesting to be devoting an issue of Kosmos to the Ageless Spirit, honoring both the vast body of wisdom teachings that have been passed down through the centuries AND those many wise elders (including some who are young in years) who are today bringing fresh insight to these teachings as they apply to the mind and heart of our age.

And what an age it is! The world right now, in all its intensity, can seem to be a chaotic complex of contradictions, conflicts, stresses and tensions. And as time goes on it only seems as if this intensity is mounting. As we become increasingly aware of how interdependent we are as a species, crises in the body politic are, not surprisingly, coalescing – mirroring that interdependence. As Oxfam International Executive Director, Amitabh Behar, recently declared while speaking at the UN, we are facing “a poly-crisis: a climate emergency, a cost-of-living crisis, an inequality crisis, a crisis of democracy back-sliding”. Readers of Kosmos recognize that the coalescing crises in society and international relations are also reflected in every profession, in science and technology and, most importantly, they reach into the depths of the psyche of our most private and intimate lives. As communities, nations, peoples and as individuals we are in crisis.

So, what’s going on? How does this chaos in the world affect our relationship with the great Wisdom Teachings that have played such a critical role throughout human history? Is the Ageless Spirit simply a way of escaping from the ‘real world’ and turning our backs on all the gritty questions of our age, as some might suggest? While of course the inherited wisdom of the ages can be approached in a whole variety of ways, some of which may be disempowering and escapist, I think that something different is at play here. If there is one thing that most teachings agree on it is: what’s wrong with crisis? Crisis transforms. Bearing in mind the oft quoted thought ‘never waste a good crisis’ – this is a time to welcome and appreciate breakdown as a sign that some sort of existential change is on the way. It’s a time to shift our focus and direct our attention to signs of breakthrough.

More than anything else, the intensity of these times challenges us to deepen our own orientation to the Real – and to our intelligent appreciation of future evolutionary possibilities that are being worked out in our lives and through our lives. And that is why the Wisdom Teachings are so important right now. We are being called to really think – and to explore what it means to think for ourselves, rather than be molded in our thinking by either the fears and insecurities of those around us, or by loud voices seeking to persuade us of one ‘right’ way of responding to these times. The Teachings give us a new map of Reality, and a way of seeing that spirit is alive and at work in all the matter and substance of our lives. It is then down to us how we interpret these teachings in the face of today’s realities.

Evolution, as I understand it, is pushing us all to think and feel in fresh and quite new ways. A reorientation to the Real (with its limitless dimensions of Joy and Beauty, Love and Purpose) is about going deeper so that our intelligence, creativity, and instinctual behaviors can be more oriented around and inspired by depths of wisdom that lie within us and can drive the emergence of an entirely new culture where science, religion and spirituality can become whole again and mystery, spirit and myth re-emerge in all the professions and social organisms.

Ancient wisdom that has been passed down through the ages has the power to lift modern thought into a new fascination with time-honored qualities like selflessness, healthy self-forgetfulness, sacrifice, service – all the ways in which the love of the soul truly breathes in and through our lives and our cultures. Only a serious, deep encounter with the ancient wisdom teachings (in their diversity) has the power to do this.

There is a purpose that lives in our soul or Essential Self, our own unique Buddha Nature. And in this moment of crisis that deep purpose is pushing itself, at times quite forcefully, through into the awareness of more and more of us – as individual units as well as into the shared thinking of groups and networks. That pushing into awareness can be a source of disorientation as everything we thought was real and true and substantial begins to be seen in a new light. To counter this, visions, goals, and disciplines must be re-discovered and re-envisioned.

It is here, as we rediscover what it is to be human in a world in transformation that the Wisdom Teachings of the ages can be seen to be so vitally important. For the teachings, considered as a whole body of thought – a perennial wisdom with a wealth of myths and stories and insights into the Real – are what give our minds and our hearts access to the new consciousness that is coming in. We need these maps and guides to help us navigate afresh our way out of materialism and into some new and as yet undefined culture of synthesis where the material world and the spiritual world sit together in a more creative and enriching way.

This sort of process of realignment can inspire a quiet persistence and an almost timeless sense that everything (absolutely everything) is about unfolding qualities of relationship: between personality and soul or vision, identity, thought and emotions; between individual and group; between groups; between kingdoms of nature; between the Earth and the Cosmos.

While the notion of Emotional Intelligence is now well established in thoughtful conversations we are still not so familiar with what Danah Zohar and Ian Marshall refer to as Spiritual Intelligence: the “intelligence with which we access our deepest meanings, values, purposes, and highest motivations. It is how we use these in our thinking processes, in the decisions that we make, and things that we think it is worthwhile to do …. Spiritual intelligence is our moral intelligence.”1 It is here that the Wisdom Teachings become our guides and protectors. They provide us with an understanding of how, through individuals and groups around the world, the mind and soul and spirit are again coalescing in ways that are already shaping a new world.

As Ian McGilchrist reminds us “attention is a moral act”. As more and more of us develop a long-term encounter with the wise teachings of the ages we are developing the muscles and discernment needed to navigate our own authentic ways of attending to the world and to the relationships within the world. And, I suspect, that many of us are doing so in response to the intensity of the crises of this time.

Return to Ageless Spirit Contents Page

1. Daana Zohar and Ian Marshall, Spiritual Capital: Wealth We Can Live By. San Francisco, Berrett-Koehler. p.

Earth, Our Eldest Teacher

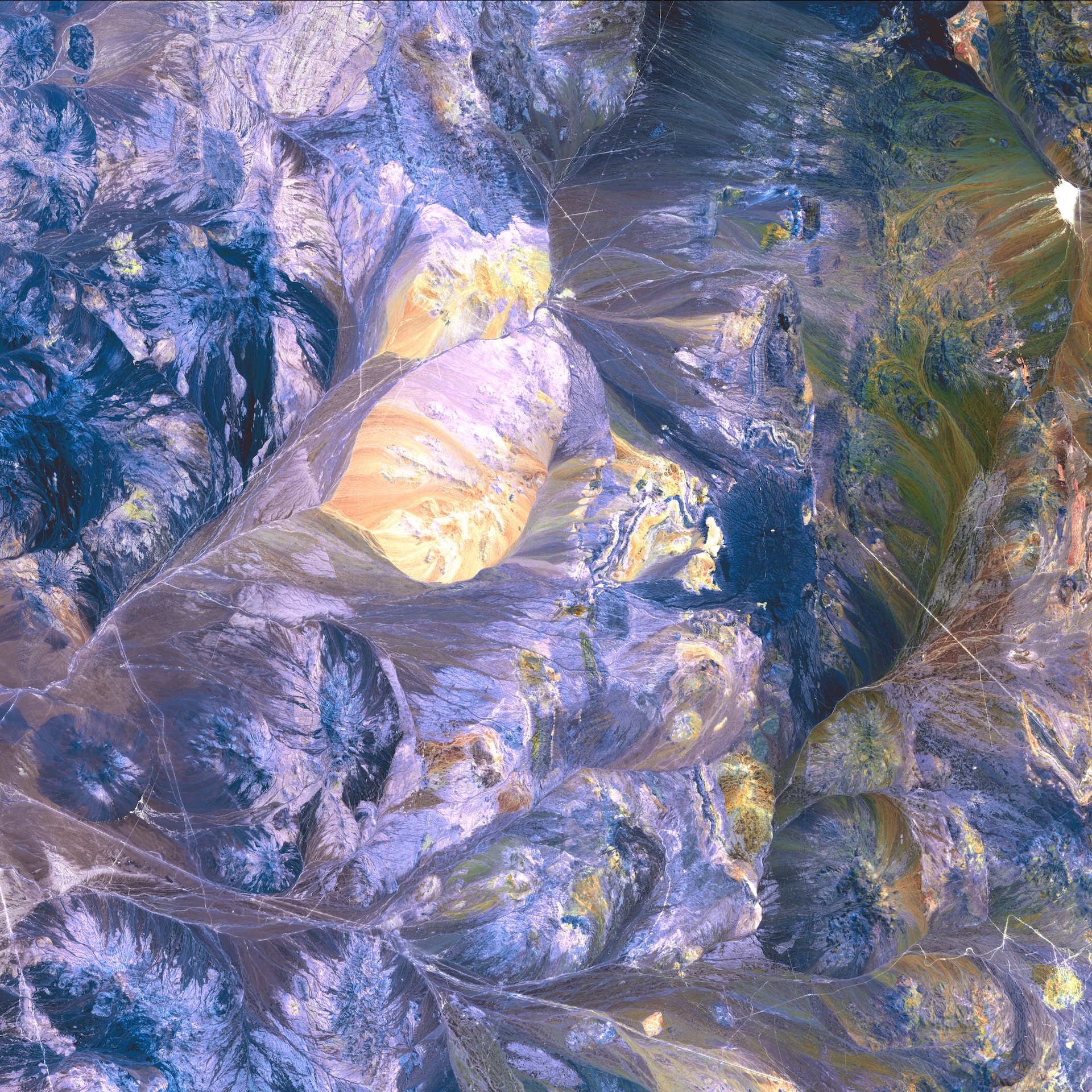

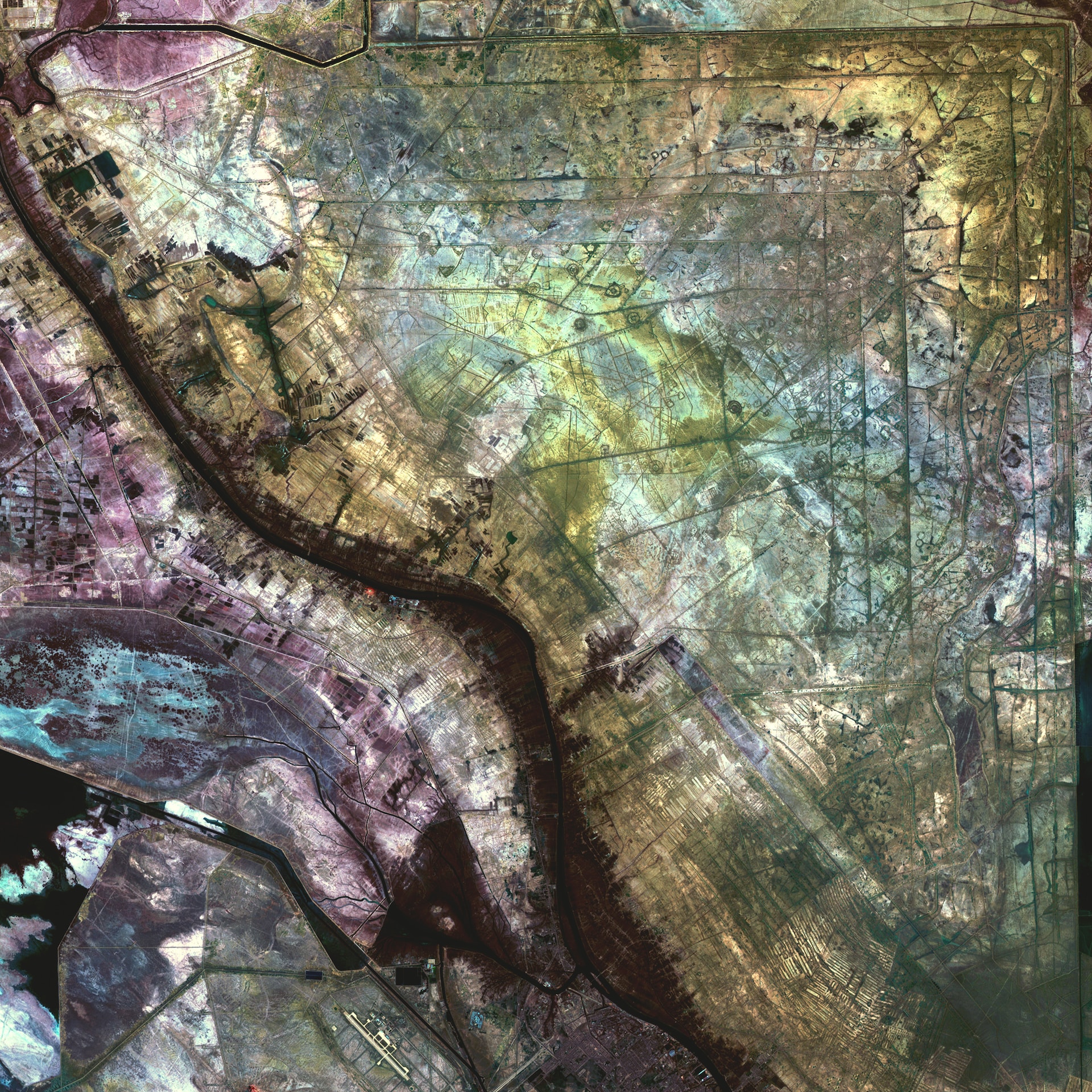

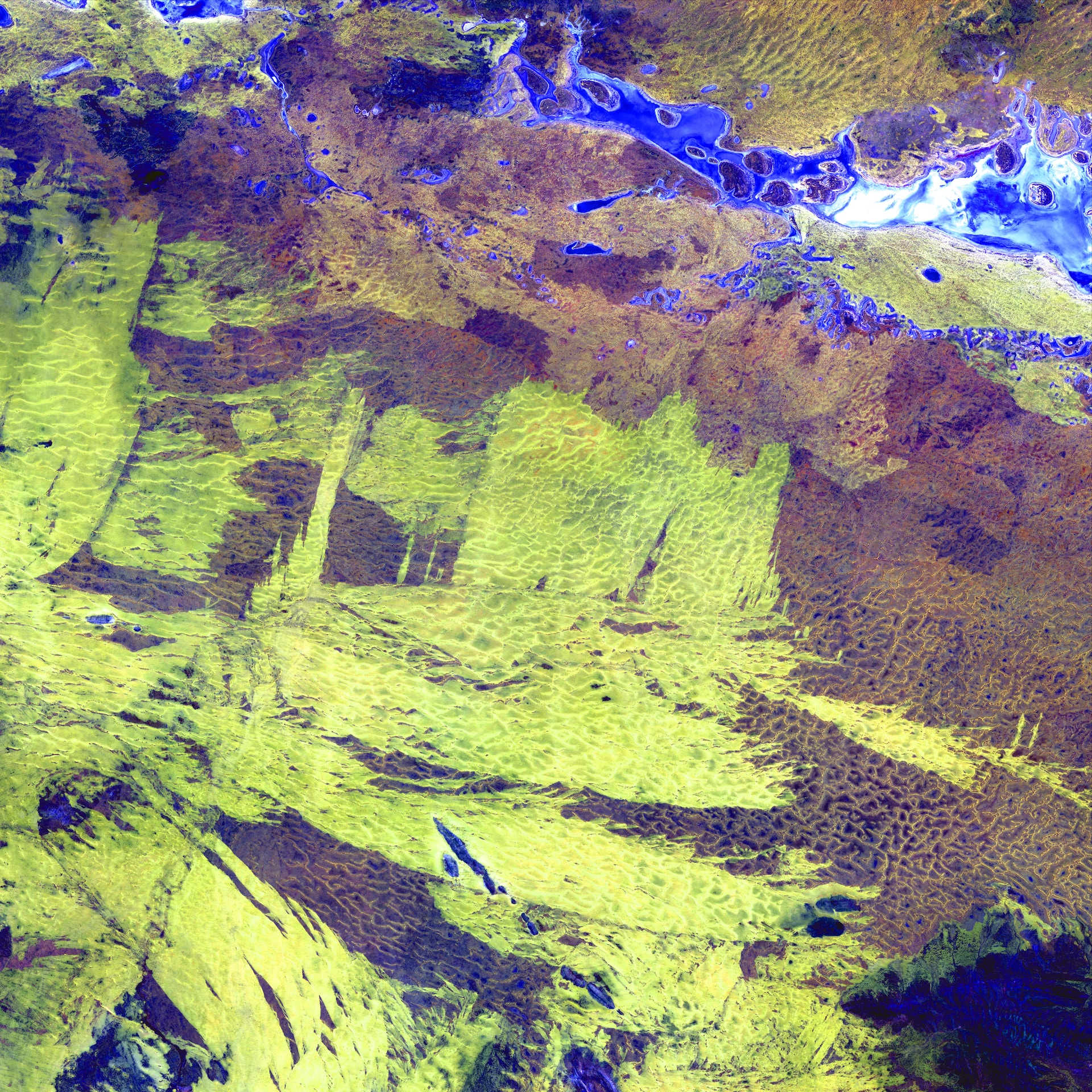

All images | US Geological Survey

About Steve Nation

Steve Nation who has worked for much of his adult life with World Goodwill and Lucis Trust offices in New York and London, is co-founder of Intuition in Service and the United Nations Days & Years Meditation Initiative. He distributes a monthly newsletter on global events and conferences, ‘Please Hold in the Light’. Steve is a member of the Council of the Spiritual Caucus at the United Nations, and he takes a special interest in the work of the Darjeeling Goodwill Centre and the Darjeeling Goodwill Animal Shelters in India. .

Attuned | Global Social Witnessing

Attuned | Global Social Witnessing

War isn’t new; violent conflict is an ancient, disrelational habit familiar to nearly all human societies. What is new about war and other mass-traumatization events in the twenty-first century is the presence of the internet and social media, namely the ease and power of so many to upload images and videos from the battlefield in real time.

For the first time in human history, wherever we are and no matter how far away, we can witness and react to what’s happening in active conflict zones or disaster scenes a world away. Even if we choose to avoid social media and online or television news, it can be difficult for most people to miss what’s happening around us. Bad news, like gossip, is pervasive—and it spreads: an adaptive evolutionary strategy that promotes survival, though if prolonged, it promotes social dysfunction and breakdown. Despite the unprecedented access to information now available, we are often not so much well informed as we are overwhelmed. And if not overwhelmed, we’re likely desensitized, numb, cynical, or shut down.

Modern media sensationalizes news of violence, threat, and danger, profiting off human fear and furthering societal polarization. The massive onslaught of polarizing data we consume is not immediately digestible. In fact, unfettered access to information about active trauma may create what researchers have called secondhand or vicarious traumatization, especially for the highly empathetic person. At the very least, constant news of human struggle, violence, and adversity can result in burnout and compassion fatigue. Yet, the more anesthetized we become to the suffering of others, the less capable we are of responding with discernment and wise action to help end or prevent further suffering in the world. Without knowing it, we may become complicit in the ongoing repetition of humanity’s darkest cultural traumas through unconscious activation of the hidden energies that make trauma possible in the first place.

What would trauma-informed media look like?

Sensational news headlines and divisive online engagement activate trauma patterns within the collective unconscious, amplifying apathy and indifference at one end and heightening emotional disruption at the other. News media websites and social media apps are coded for “increased engagement,” because more clicks mean more dollars for shareholders. To support this unwieldy and unethical financial model, artificial intelligence algorithms are designed to push ever more extreme controversy, fear, and antagonism, thereby privileging “incendiary content, [and] setting up a stimulus–response loop that promotes outrage expression.”

The end result has been increased social polarization and conflict, poor mental health outcomes, and further extremes in economic inequity. Is it any wonder that depression, anxiety, addiction, and self-harm are exploding among young people?

What would trauma-informed media look like? It’s a question that deserves critical research. What’s clear is that contemporary societies need to focus as much or more attention on healing and health as they do on increasing gross domestic product. Imagine a new media and economic landscape that is grounded, professional, and ethical, whose leaders value human health above personal profit. Imagine global news media that engenders wider understanding and compassion as it informs us.

You see, collective trauma is not an academic abstraction or even a sociological concept. In the most real sense, it is the mass of unmetabolized energy that exists within and all around us as a result of toxic stress, adversity, shock, and trauma. Even if we don’t know it’s there, the energy of mass trauma affects us. All of us. It shapes our lives and alters our relationships, our communities, and the natural world around us.

There is nothing left untouched by collective trauma. In fact, its nature is so ubiquitous and its effects so insidious that we have come to consider it “normal.” This is just how things are. Just how families are. Just how people are. Just how the world is. Yet nothing could be further from the truth. Integration allows us to harvest the frozen, disclaimed energies of the past and use them to illumine our perspective in the present. As the great German writer, scientist, and statesman Johann Wolfgang von Goethe observed, “Man knows himself only to the extent that he knows the world; he becomes aware of himself only within the world and aware of the world only within himself. Every new object, well contemplated, opens up a new organ of perception in us.”

By opening ourselves to the exploration of trauma’s effects within and around us, we come to know more of ourselves, the world, and one another. After all, only what we acknowledge can be integrated—and the integration of trauma becomes post-traumatic learning. Integration allows us to harvest the frozen, disclaimed energies of the past and use them to illumine our perspective in the present.

What’s more, healing the ethical transgressions of the past develops our ethical understanding today. This wisdom is vital if we wish to meet contemporary ethical challenges: from questions about artificial intelligence, nano tech, genetic engineering, cyberwarfare, new weapons of mass destruction, and other evolutionary concerns. Perhaps one day, a mandate to reckon with and heal historical and collective trauma will be written into the constitutions of nations.

To begin to address the phenomenon of collective trauma at its source, I developed an awareness-based practice called Global Social Witnessing (GSW). GSW is a social mindfulness practice that shows us the limits of our capacity to be a present witness to events—including and especially to traumatic events—that are reported within society.

Through sustained practice of GSW, we begin to see into the gaps, the places where we may intellectually understand the facts of the news stories we consume, but where we become emotionally or even physically stressed and overwhelmed by the contents or where we alternately shut down and numb, potentially unaware that relation has been lost. When this occurs, we are no longer in witness. The gap itself represents the distance (or incongruence) between one’s interior and exterior and contains the unprocessed collective trauma we carry within. We practice GSW to help make the collective trauma field more visible so that step by step, we can begin to integrate the internal fragmentation we all carry.

In its simplest form, GSW is the act of consciously presencing, witnessing, sensing, and feeling into the dense energies of adverse current events—whether the stream of alarming news stories pouring across your daily newsfeed or the sudden outbreak of war in Eastern Europe. Global Social Witnessing can be initiated as an individual practice or facilitated in a group context, even with very large groups. And it is meant to be used in a titrated fashion; as practitioners, we take on one adverse current event at a time.

To address trauma, we must meet it at the root. We must engage in a practice of making conscious that which is unconscious. We must choose to notice, feel, and digest the energies we otherwise instinctively resist, suppress, avoid, disown, and deny. Global Social Witnessing is a practice for being with the difficult energies of the large-scale traumatic events occurring in the world around us: ongoing wars in nations like Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, Ethiopia, and elsewhere; the mounting cartel violence in South and Central America; continuing civil unrest, armed violence, and human rights abuses in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Myanmar, Republic of Congo, and beyond; the oppression and genocide of the Uyghur people of China; and the many other human and planetary wounds that call out for our care and attention. Without our care and attention, these compounding traumas will continue unabated. Human rights can only be honored and preserved through genuine relatedness. It is the lack of relatedness that makes the violation of human rights possible.

Global Social Witnessing is a form of dialogic inquiry—defined by one scholar as “the tool kit of discourse in the activity of learning”— in which together we presence the collective field so as to mindfully attend to global events with embodied awareness. In practice, GSW is a model that allows us to make visible the invisible forces that influence our lives in order that we may apprehend and transform them.

Practice | Global Social Witnessing

Search for a disquieting piece of news about current events—a headline or news article, for example—to bring into your practice. It should be information that’s difficult or upsetting, without being too overwhelming.

The story you choose could be about a school shooting, a local act of violence, or a story about climate change— whatever feels important to focus on.

Now sit down, and as you read the news headline, check in with your body, noticing any sensations, feelings, images, or impressions that arise. Are you reading the headline intellectually but feeling emotionally or physically numb or disconnected? Do you experience an activation of fear, stress, or upset? Or do you notice a sense of felt connection to the event?

The point of the practice is not to be able to feel or sense the event; the point is to see our limitations. We practice GSW in order to become aware of our “edge,” where the capacity for being an embodied witness stops. The end of your ability to sense and feel marks the beginning of the collective unconscious, or collective absence. The overwhelming nature of the information reduces the function of collective witnessing, or presence, so that the energy of these events doesn’t get processed or reconciled and must therefore repeat.

Widespread use of the internet and mobile devices makes us think of ourselves as super informed, yet numbness, absence, and overwhelm are all too common. These responses to collective trauma prevent us from fully metabolizing the information we experience. However, we can all be more mindful about how we consume the news and engage in the Three-Sync Practice as we do so.

A GSW practice can also be powerful in groups, where members of the group share their inner experience with others who bring their attunement, presence, and witness to the whole.

Global Social Witnessing invites us to align our individual interiors within a wider collective and intersubjective container. When we practice, it is our shared intention to tune into self and other—and to the interior and exterior worlds at the same time. The practice of GSW strengthens our capacity to host the Other within, to embrace the Other with a shared heart. Through the GSW practice, we become more mature global citizens, better equipped to co-create new ideas and approaches for transforming the dense energies of disruption into the vitality of future innovation.

As global citizens, it is incumbent upon us to express global citizenship. We must also recognize the fundamental human responsibility we share, which is to practice making conscious the dark energies of human suffering so that those energies can be digested, integrated, and returned to the life flow of future potential.

Whole states must address the social wounds created by war, colonialism, racism, anti-Semitism, gender violence, and environmental degradation. When done in earnest, this work restores the flow of light, or conscious awareness, to the collective body and makes healthier and more sustainable societies possible.

Gus Speth, the American environmental lawyer and former US senior advisor on climate change, has said, “I used to think that top environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and climate change. I thought that thirty years of good science could address these problems. I was wrong. The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed, and apathy, and to deal with these we need a cultural and spiritual transformation.”

Speth is right, of course, though it’s important to note that the selfishness, greed, and apathy he mentions are in truth only symptoms of the larger problem, which is our unaddressed collective shadow and unhealed collective trauma. It is our willingness to awaken to, experience, and transform these root causes that creates the cultural and spiritual transformation Speth prescribes.

We can think of the global immune system as a refined resonance capacity. It represents the most essential, ancient, and evolutionary wisdom for dealing with the reactive mental, emotional, and psychosocial aspects that arise within us in response to the traumatic residue and accelerating disruption all around us.

R egardless of how far removed we may be physically from unfolding unrest or atrocities—in Ukraine, Yemen, Ethiopia, Haiti, Myanmar, Israel, Palestine, and elsewhere—we are no less affected by them. And it is precisely because we are touched by these events that we have the power to help shift them. Collective healing starts with the immune reaction, the experiences that come up inside us when we’re faced with the realities on the ground or in media reports and images shared during active conflict. Even as distant observers, we can feel disturbed and activated by these events, which can show up in many forms: fear, terror, anger, outrage, numbness, or shutting down.

egardless of how far removed we may be physically from unfolding unrest or atrocities—in Ukraine, Yemen, Ethiopia, Haiti, Myanmar, Israel, Palestine, and elsewhere—we are no less affected by them. And it is precisely because we are touched by these events that we have the power to help shift them. Collective healing starts with the immune reaction, the experiences that come up inside us when we’re faced with the realities on the ground or in media reports and images shared during active conflict. Even as distant observers, we can feel disturbed and activated by these events, which can show up in many forms: fear, terror, anger, outrage, numbness, or shutting down.

Yet it’s our power to simultaneously feel and witness our feelings and reactions that allows us to digest and integrate some measure of the overall trauma energy. This is the collective immune response in its most conscious and participatory state. And it is vitally urgent that we learn to engage in collective self-healing. The global immune system is the organ through which we become activated by disturbance in the field, but it’s also the instrument through which we may more consciously attune to the world around us in order to integrate that disturbance and restore balance to the living system.

Only a small number of us—a critical mass if you will—is required to engage before a new level of collective coherence becomes established in sympathetic resonance, ringing like a tuning fork across the field, inviting the entire world to join.

Excerpted from Attuned: Practicing Interdependence to Heal Our Trauma―and Our World by Thomas Hubl. Sounds True, September 2023. Reprinted with permission.

About Thomas Hübl

Thomas Hübl, PhD, is a renowned teacher, author, and international facilitator who works within the complexity of systems and cultural change, integrating the core insights of the great wisdom traditions and mysticism with the discoveries of science. Since the early 2000s, he has led large-scale events and courses on the healing of collective trauma, with a special focus on the shared history of Israelis and Germans, and facilitated healing and dialogue around racism, oppression, colonialism, and genocide. He has served as an advisor and guest faculty for universities and organizations, and is currently a visiting scholar at the Wyss Institute at Harvard University.

First There Must Be an End

First There Must Be an End

Featured image | David McMillan: Growth and Decay

The following is an excerpt from Dougald Hine‘s new book At Work in the Ruins (Chelsea Green Publishing February 2023) and is printed with permission from the publisher.

Here are two claims I have found that I can steer by.

Here are two claims I have found that I can steer by.

The first comes from the closing lines of a manifesto that a friend and I wrote, nearly fifteen years ago now: The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world, full stop. Unless we can inhabit that distinction, we will end up defending the world as we have known it at all costs, no matter how monstrous those costs turn out to be. Think of the desperate schemes for geoengineering already being drawn up. Think of the walls being built to defend against those already displaced by changing patterns of sea, rain and heat. How we name what is at stake will determine what we are prepared to do.

The second claim came out of the conversation started by that manifesto: The end of the world as we know it is also the end of a way of knowing the world. When a world ends, its systems and stories come apart, even the largest of them: the stories that promised to explain everything, the systems that organised all that could be said to be real. It’s not that those stories had no truth in them; it’s not that there was no reality in the description of the world those systems offered. It’s that they couldn’t hold. The things they valued betrayed them; the things they left out came back to haunt them.

One name for the world as we have known it is modernity; one name for its way of knowing the world is science. So [my book, in part, is] about navigating the end-times of modernity and what happens to science as its world ends.

***

Here’s one more story from the Covid spring. I remember this post like a message in a bottle, thrown into the storm of social media, back in those first weeks. It was lost in the tide of memes and takes, I don’t know how to find it, but the author was a climate scientist. Already the lines were being drawn and there was a take going round that went like this: ‘Has anyone noticed how the people refusing to follow the Covid science are the same ones who refuse to accept the climate science?’ Hang on a minute, this climate scientist said, it’s taken decades of careful work to be able to say with confidence the things that my colleagues and I can tell you about climate change. Please don’t treat that as equivalent to what it’s possible to say about a virus that was only identified a few weeks ago.

The iterative nature of the work of science means that the state of knowledge will vary from field to field. With a new object of study, it’s hardly surprising if what the researchers think they know turns out to change from week to week, in contrast to the well-grounded consensus that can emerge in a mature field. But the political rhetoric of ‘following the science’ disregards these differences, casting a singular authority over whatever is said in the name of science, so that the first provisional findings about a new disease are presented as though they were established certainties.

Science in general – and climate science in particular – is not well served by this ideological conflation. Yet, this is a problem that runs deep because the multitude of methods and practices that make up the work of science have been entangled for centuries with a singular story that grants this way of approaching the world a monopoly on telling us what is real. It places a burden on the scientists’ shoulders that was always going to prove unsustainable, but we are living through an intensification of this logic that will push it to breaking point.

One of the questions running through this book is how far, and in what shape, the work of science might survive the end of the world in which the story of science took shape. I might as well say now that I don’t have an answer; it’s not the kind of question that can be answered with a book, but what a book can do is make an invitation to the kinds of conversations and encounters that might be called for, that might help us find some paths into the unknown world that lies ahead.

***

‘In these times, all we can do is be a sign,’ a father tells his daughter in Ben Okri’s novel The Freedom Artist. ‘We have to help to bring about the end of the world.’ We must do this, he goes on, so that a new beginning can come. ‘But first there must be an end.’1

It matters which world we think is ending, and it matters what we tell each other is worth doing in such a time. Among the people we’ll meet in the story I tell, are those who have dedicated their lives to the study of climate science, those taking desperate measures as activists to break the trance they see around them and those inside existing institutions who have been shaken to the core by what we know and what we have good grounds to fear about the trouble in which we find ourselves. There can be a danger in allowing that trouble to be defined solely in terms of climate change, but I’m convinced of the importance of each of these roles in these times. I’m also convinced that other roles need playing and other kinds of action are called for. There’s a lot to be unfolded along the way, but let’s have some leads to get us started, taken from a few of those who have helped to shape my thinking.

First there must be an end – but many kinds of end are possible. My friend Vanessa Machado de Oliveira wrote a book called Hospicing Modernity.2 The title invites us to a kind of work in which the focus is not on saving modernity, or bringing it down, or rushing to build what comes afterwards, but doing what we can to give it a good ending. To let it hand on its gifts and teach the lessons that may only become apparent as the end approaches.

‘It may seem like this book is trying to kill or destroy modernity by announcing its death,’ she writes, but this is ‘something no book can do.’ It’s a warning that applies here, too.

No one I’ve met has more to offer by way of tools for the work of hospicing, but the way Vanessa tells it, this must be accompanied by a work of midwifery: assisting with the birth of something new, unfamiliar and possibly (but not necessarily) wiser, and avoiding suffocating this new world with our projections.

The philosopher Federico Campagna speaks about living at the end of a world.3 In such a time, he suggests, the work is no longer to concern ourselves with making sense according to the logic of the world that is ending, but to leave good ruins, clues and starting points for those who come after, that they may use in building a world that is – as Vanessa would say – ‘presently unimaginable’.

They may be here already, the builders of that world. Some of them may have been here all along, inhabiting the ruins made by the world of the powerful. The anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing wrote a book called The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins.4 That could be a role to take in times like these, to go looking for possibilities of life among the ruins around and ahead of us.

I don’t write to announce the end of the world or to change the minds of those who are convinced that the world as we have known it can be saved or made sustainable. I write for anyone who has found themselves, as I have, needing to make sense of what is ending, how we can talk about it and what tasks are worth taking on in whatever time it turns out that we have.

Something is coming over the horizon: a humbling from which none of us will be spared, that will not be managed or controlled, but will leave us changed.

Before it is over, I suspect, we will need to learn again what it means to take seriously things that are larger or smaller than were allowed to be real or significant, according to the scales and systems of modernity. We will need to dance again with the rhythms of cosmology, to be carried by the kind of stories and images in whose company – as the mythographer Martin Shaw would say – a universe becomes a cosmos. We will need to remember that we are not alone and never were, that we are part of a world of many worlds, only some of which are human. And we will need to rediscover that any world worth living for centres not on the vast systems we built to secure the future, but on those encounters that are proportioned to the kind of creatures we are, the places where we meet, the acts of friendship and the acts of hospitality in which we offer shelter and kindness to the stranger at the door. In this way, even now, there may be time to find our place within the vastly larger and older story of which we always were a part.

footnotes

1 Ben Okri, The Freedom Artist (Brooklyn: Akashic Books, 2020), 211.

2 Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2021).

3 Federico Campagna, Prophetic Culture: Recreation for Adolescents (London: Bloomsbury, 2021).

4Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

About Dougald Hine

Dougald Hine is a social thinker, writer and speaker. After an early career as a BBC journalist, he cofounded organizations including the Dark Mountain Project and a school called HOME. He has collaborated with scientists, artists and activists, serving as a leader of artistic development at Riksteatern (Sweden’s national theatre) and as an associate of the Centre for Environment and Development Studies at Uppsala University. At Work in the Ruins concludes the work that began with Uncivilization: The Dark Mountain Manifesto (2009), co-written with Paul Kingsnorth, and is his second title with Chelsea Green, following the anthology Walking on Lava (2017).

photo credit: Ingrid Rieser

Searching for a more beautiful world, with Charles Eisenstein

Searching for a more beautiful world, with Charles Eisenstein

featured image | Alex Grichenko

This interview first appeared at Tam’s blog on Medium, where you can read it in full: HERE

From a young age, Charles Eisenstein has felt something was fundamentally wrong with our world or, more specifically, with the social and political realities we have built. My intuitions — my heart- and gut-based modes of understanding — have been cultivated by Eisenstein’s work. Yet, his work is not anti-rational. He has a strong background in analytical methods, mathematics and philosophy. We conducted the following interview by email.

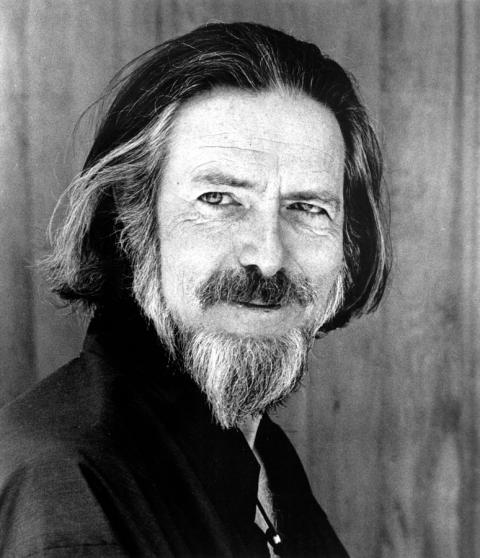

Tam | Let’s start with your background and motivations for your work. You went to Yale for your undergraduate studies and focused on mathematics and philosophy. Your first major book (2007) was The Ascent of Humanity, which you suggest in that book itself was a work that took a decade or more to research and write. What inspired this effort? Who are the major thinkers you looked to in forming your ideas?

Charles | That book embodies at least a decade of study and thought, but I was actively writing it for just four years. Some key influences were Wendell Berry, Ilya Prigogine, Lewis Mumford, Marshall Sahlins, David Bohm, Helena Nordberg-Hodge, Lynn Margulis… I could name some others, but really this is not primarily a scholarly book, and the list of influences won’t help much to understand it.

Tam | You write in the introduction to your 2013 book The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible that you are an ordinary person and if you, an ordinary person, can seek and achieve these insights and these practices in your life, then almost anyone should be able to. I don’t wish to detract from your efforts to paint yourself as an ordinary guy but it seems pretty clear that you have spent an extraordinary amount of time reading, researching and writing about a vast number of topics, from spirituality, to economics, to science, to climate, to currencies, to political movements. Doesn’t the effort you’ve expended in itself make you at least a little extraordinary?

Charles | Sure, why not. My point, though, is that the insights didn’t come from a dramatic life story or unusual discipline. They are quite close at hand for ordinary people, because really what I am doing is to give voice to a new mythology that is rising in the collective consciousness.

Tam | How would you sum up the key points of your work? Despite the breadth of issues you’ve written and spoken about, there is a theme that runs through your work. You write very accessibly and your target audience seems to be anyone who wishes to listen (rather than writing for a niche field of professionals, for example). Why have you chosen to write for the “everyperson” rather than more niche audiences?

Charles | The overarching theme of all my work is the transition in civilization’s defining mythology, from a story of separation to a story of interbeing. This transition plays out in all the fields I write about, and provides a way to identify common patterns across those fields. Because I am what you might call a “generalist,” my work is accessible to laypeople. I am myself a layperson, albeit highly educated in certain fields.

Tam | You moved to Taiwan in your 20s, studied Chinese, and worked as a translator for some years. What caused your life to take this particular turn? Are you still conversant in Mandarin?

Charles | Yes, I am still fluent in Mandarin, although I seldom have opportunity to speak and have forgotten a lot in the 25 years since I lived there. I went to Taiwan right out of college, because I felt like such an alien in my home country, and I couldn’t make myself get with the program. I had no ambition whatever to become a success, build my resume, go to graduate school, or anything like that. Furthermore, living abroad gave me the opportunity to discover who I was apart from the reinforcing circumstances of my home culture.

Tam | How much does your fluency in another language and culture, quite different than US culture, influence your thinking and willingness to propose ideas that are radically different than the mainstream?

Charles | Well, there are certainly plenty of multilingual people around, and not all of them are creative thinkers. But I think in my case, immersing in a radically different language and culture prevented my intellectual programming from calcifying. I was introduced to entirely new categories of thought before the old ones had fully formed.

I also have to credit psychedelic medicines for exposing the narrowness and artificiality of what I’d until then accepted as real. They helped open my mind to different ways of conceiving and perceiving the world that local traditions of Buddhism and Taoism offered. I never studied either deeply, but they suffused the cultural atmosphere and influenced me profoundly, particularly Taoism.

One influence I can say that Chinese has had on my later work is that it helped me work more comfortably with paradox. It is in many ways a less precise language than English; the same is true of the various Taoist sciences. You don’t start with basic definitions and first principles and work your way up from those. Taoism applies a more holistic logic and employs more teleological thinking. To some extent, this is embodied in the Chinese language too. Grammar is more fluid, words can morph from one part of speech to another, and the “atoms” of the language are semantic and not alphabetic. Aphabetic languages offer a model of reality in which meaning is an illusion. Just as meaningful words are composed of meaningless letters, so also is the meaningful world composed of meaningless protons, neutrons, and electrons. Chinese is not like that: meaning in Chinese is elemental. Perhaps these feature of the Chinese language primed me to explore non-reductionistic thinking and the relationship between story and reality in my later work.

One influence I can say that Chinese has had on my later work is that it helped me work more comfortably with paradox. It is in many ways a less precise language than English; the same is true of the various Taoist sciences. You don’t start with basic definitions and first principles and work your way up from those. Taoism applies a more holistic logic and employs more teleological thinking. To some extent, this is embodied in the Chinese language too. Grammar is more fluid, words can morph from one part of speech to another, and the “atoms” of the language are semantic and not alphabetic. Aphabetic languages offer a model of reality in which meaning is an illusion. Just as meaningful words are composed of meaningless letters, so also is the meaningful world composed of meaningless protons, neutrons, and electrons. Chinese is not like that: meaning in Chinese is elemental. Perhaps these feature of the Chinese language primed me to explore non-reductionistic thinking and the relationship between story and reality in my later work.

Tam | Were you always comfortable with being considered a radical? In my own experience studying various fields and finding myself coming to very different conclusions than the mainstream I’ve realized that there must be significant other factors than logic or evidence influencing whatever ideas or theories are most prominent — because so many of them just don’t make sense under scrutiny. I’ve thus found myself comfortable with being in many ways “on the fringe” but it’s not something I sought out. Have you experienced a similar dynamic in your intellectual meanderings?

Charles | I have long and frequently felt a bit of an alien here. Until recently, that has mostly meant being ignored and dismissed, a mostly benign neglect outside the corner of the culture that comprises my readers. That has changed with the pandemic, when ideas that I’ve written about for years all of a sudden attracted much more attention, much of it hostile. For example, in The Ascent of Humanity there is a section titled “The War on Germs,” in which I located conventional medicine within larger paradigms of conquest and offered quite specific critique of certain medical practices. But it was only in the last two years that such views drew public denunciation and cancelation — including by the very publisher who now carries that book. If I may flatter myself to say that my views are true, I can only hope that they exemplify Schopenhauer’s adage: “All truth passes through three stages. First it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.”

Tam | You describe in your work how you’ve had a feeling of discontent and of fundamental wrongness with modern society from an early age. When did these feelings and realizations first happen to you?

Charles | It began very early on in grade school. I couldn’t have articulated the feeling at the time, but I just couldn’t accept my situation as good and right, sitting in rows in the classroom, forced to do things I didn’t care about, filling out worksheet after worksheet, watching the clock tick slowly toward recess. I was quite timid, but I remember secretly siding with the “bad” kids and glorying in their insubordination.

As a teenager, I began encountering books that fueled my latent indignation. I read Orwell, Solzhenitsyn, Rachel Carson, Wendell Berry, and so forth. I knew then that I wasn’t crazy for believing something was fundamentally wrong in the world. I also began to suspect that the origin of the wrongness was much deeper than anyone knew. That is how I became a radical.

Tam | Shifting to less personal questions, how do you respond to the Pinkerian argument that the Enlightenment has improved the world in countless ways? Pinker has argued in two hefty books (The Better Angels of Our Nature and Enlightenment Now) that the Enlightenment way of thinking, led by science and reason, has indeed led to a vastly better world in numerous quantifiable ways. He presents data in dozens of categories showing that the world is far better off in terms of declining violence, longer lifespans, better standard of living, access to health care, declining child death and death of mothers during birth, etc. You of course paint a very different picture in your work, of a world on a fundamentally wrong track. So what does Pinker get wrong or leave out?

Charles | I could answer by pointing you to an essay I wrote in response to Pinker: Our New, Happy Life? The Ideology of Development. It is not possible to rebut his thesis in a few short paragraphs, when such a rebuttal requires overturning deeply held assumptions. His book was so readily celebrated by powerful people in the establishment because it feels so commonsensical to them, drawing on assumptions they take for granted.