Purposeful Memoir as a Path to Alignment

Purposeful Memoir as a Path to Alignment

by Jennifer Browdy

Most people think of memoir as a recounting of what we already know about our lives. But, in fact, what we already know is only the beginning of the journey of what I call purposeful memoir, particularly when we’re looking to align the personal, political, and planetary in our life experience—meaning, to understand how our personal choices are shaped by, and affect, both the social and environmental landscapes in which we live.

This profound interconnection is expressed by the Buddhist concept of interbeing. We inter-are with everything else on the planet. The Western attitude of individualism, separatism, and exceptionalism is an illusion bred by the arrogant thinkers of the so-called Enlightenment, which was in fact the beginning of a 500-year period of gathering darkness, leading us to the crisis moment we face today.

We have all, inescapably, been part of the political and planetary patterns of our lifetimes. To take my own life as an example, I was born in New York City in 1962, the year Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published, just after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and just before the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Bobby Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr. I was too young to understand the tumult around me in my early years, and, yet, these political and planetary happenings shaped who I would become.

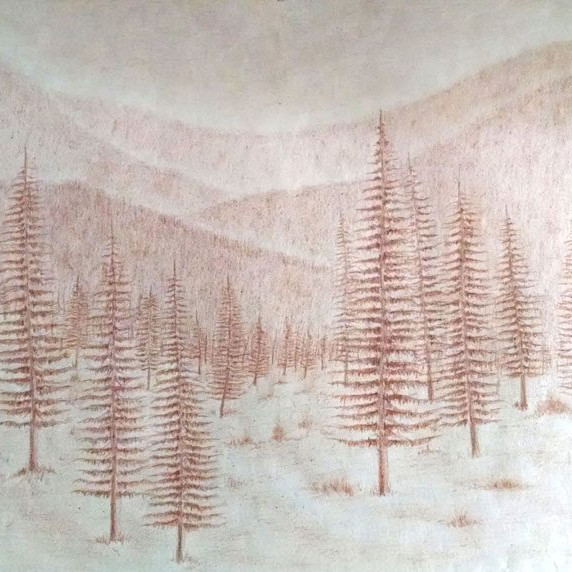

On the personal level, I knew that as a child, in what I call ‘Earth’ years up to age 12, I loved spending time out in the woods and fields around my family’s country home. What I had forgotten- and remembered in the course of writing my memoir- was how that dreamy love of communion with nature had been socialized out of me by my teenaged desire to fit in with my peers, and by my formal education.

Once I wrote my way back to that understanding, I found the purpose of my memoir: describing how my own lack of alignment with the natural world I adored was mirrored exponentially, like a creepy funhouse, by the alienation from nature of the dominant society around me.

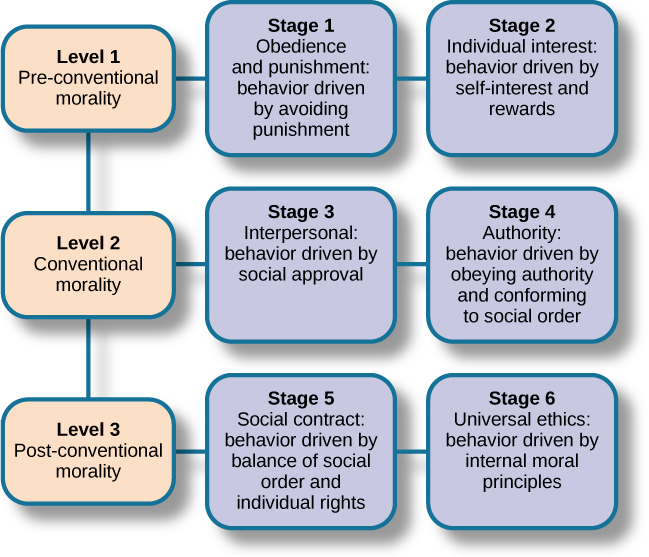

Writing my memoir was a process of unlearning what I’d been taught in what I call the ‘Water’ years of life: the teenage and young adult years when we humans tend to want to go with the flow of the society around us, seeking approval in conformity. I was catapulted into this exploration by the challenges I met in the ‘Fire’ years of my adulthood: on the personal level, divorce and career troubles; on the political level, frustration with a relentless politics of domination and destruction; and on the planetary level, waking up- horrified- to the unfolding crises of climate and ecological devastation.

Purposeful memoir that aligns the personal, political, and planetary is a tool for deeper understanding of how we got where we are today, as individuals, as a society, and as an interconnected global system.

It is also visionary: we explore the past and present in order to be able to more clearly and boldly imagine the future into which we want to live.

We look backward over our lives in order to see clearly the values and dominant narratives that have structured our relationships and guided our assumptions about what was possible. We soberly assess how we contributed to a present moment that is undeniably in crisis on the political and planetary levels. And then—in a glorious leap—we envision how we can make our own lives a strong link in the chain between past and future generations.

In purposefully following the trail of our own life experience, we follow a kind of Ariadne’s thread back out of the dark labyrinth of the present moment. It helps to have company on the journey, which is why I ended my memoir with a vision of “doing hope with others”—working together in circles of other people who have awakened to the necessity of aligning the personal, political, and planetary in the quest for a thriving future.

Writing this kind of memoir is a slow, grounded form of activism, and I believe it’s just as important as marching and shouting and signing petitions. The more of us who take the time to do the deep work of understanding our own life histories and how our individual lives have intertwined with the larger human and non-human communities on the planet, the stronger we will stand, together, as Gaian warriors who fight for Life.

About Jennifer Browdy

Jennifer Browdy, Ph.D. is a professor of comparative literature and media studies at Bard College at Simon’s Rock, where she has taught for more than 20 years. Her new memoir, What I Forgot …And Why I Remembered, is accompanied by her writer’s guide, The Elemental Journey of Purposeful Memoir, a 2017 Nautilus Award Winner. The author of many articles and book chapters, she is the editor of three anthologies of global women’s writing, as well as the online magazine Fired Up! Creative Expression for Challenging Times. Along with her online course, The Elemental Journey of Purposeful Memoir, Jennifer offers workshops in purposeful memoir internationally, as well as author-coaching, editing, and manuscript review. She writes two blogs: Transition Times, on social and environmental justice; and Writing Life, on the art and craft of purposeful memoir. Find out more at JenniferBrowdy.com.

Healing Into Consciousness

Healing Into Consciousness

Witnessing the birth of my grandchild, I was humbled in a very profound way. Looking into her eyes was like having a glimpse into the eyes of the unknown. I wondered where this newly-born child’s soul had been traveling, how her life would unfold, what her trials and tribulations on this planet would be, and what kind of gifts she brought into this world to share.

Every child is born a blank slate. No matter how loving, caring, and conscious the child’s parents are, they cannot predict what their child’s experiences will be, what lessons he/she is here to learn, and what kind of beliefs the soul will adopt from her personal experiences and social conditionings. Like the very fabric of the Universe, our human existence is complex and multidimensional. The exploration of our human condition and the discovery of our true nature is a mysterious and sophisticated journey. As we become conscious of one aspect of our existence, another is revealed to us. We are led into the arms of the unknown over and over again to discover truths about ourselves, others, and the Universe.

As humans, we have been gifted with an ability to question, explore, and discover the Truth of who we are. Though not an easy path, the longing to awaken to our True Self is built into the core of our being. Discovering the ultimate health that resides in our being is each person’s destiny, no matter how much they stray from the path of self-discovery.

I was five years old when I saw my grandfather die after battling cancer. He was in pain and very frustrated. He finally decided it was enough and grabbed a bottle of morphine that was used to ease his pain and drank from it. Shortly after, he died and everything became calm and peaceful.

Watching his lifeless body, I remember thinking that I will die one day, too. The world will continue going, just as it did after my grandfather’s death. I was suddenly taken into a different dimension of reality where I had a bird’s eye view of the impermanence of life. I knew, in that moment, that the most important things for me while I was on this planet would be to discover who I am, where I came from, and where would I go when I die.

Like everyone else, I ‘forgot’ about this important insight as life took me on its spin. Like all of us, I was inundated with conflicting ideas, beliefs, and conditionings and began to identify with them. I accumulated ideas from my parents, personal life experiences, and those that were imposed on me by social and religious structures. By the time I attained two university degrees (education and architecture), I had forgotten about the awareness of what I thought was the most important thing in life. Something inside me kept feeling misplaced, however. I did not want to fit into the structure that my parents and the world expected of me.

Fortunately, no matter how much we stray from our own path, our inner light never can be lost. Sooner or later, we will all revert back to the Truth that is undeniably at the core of our being.

After going in a roundabout way through many hardships, heartaches, and disappointments, I recognized the falsity that was all around me. I began to internally rebel and longed to find my lost inner peace and authentic Self.

I was 24 years old when I was first introduced to the teachings of George Gurdjieff and Osho. Immediately, they resonated with me and I knew that I was back on track. What they called enlightenment was the path to finding my True Self. So, I left behind what the world considered valuable in terms of a career, material success, and prestige, and, with great passion, focused on meditating and looking inward.

Things gradually began to crystalize as I embarked on this uphill path of self-discovery, which essentially meant unlearning everything that I had learned and with which I was conditioned. After several profound experiences through meditation and introspection, I experienced firsthand what dis-identifying from the body, mind, and emotions truly meant. I saw the partnership between my mind and my ego mutually feeding on all the beliefs and conditionings to stay alive.

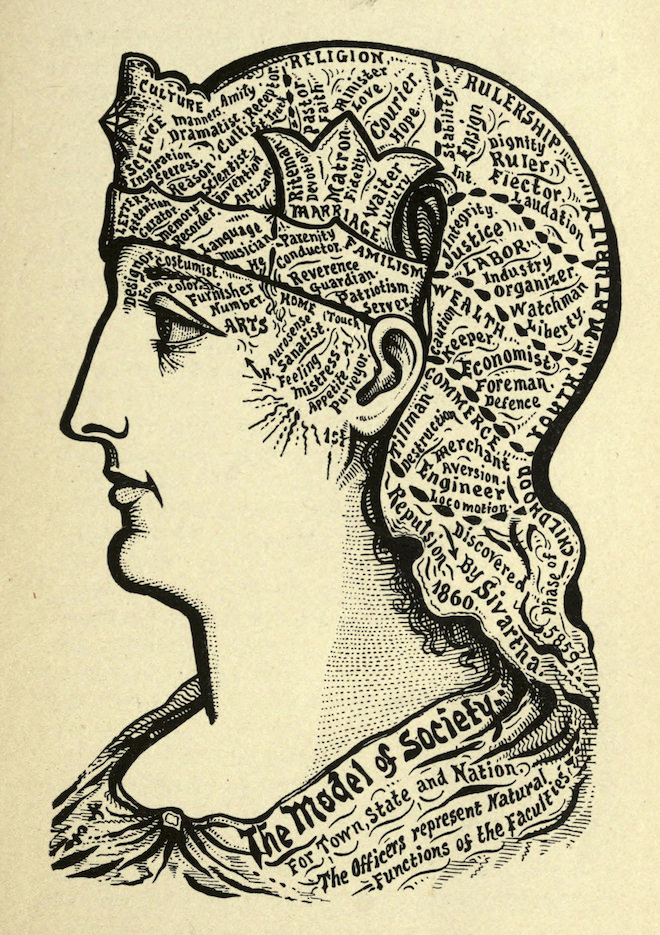

My curiosity to explore the workings of my ego-mind and observe them as a scientist of my own inner world helped me understand the ego’s fear to die and disappear into the unknown. When I gathered courage to face the fear and passed through the hurricane into its eye, I was left within the simple existence of my being which felt like an “am-ness” without anything written on it. I saw that this am-ness—which also can be called presence—was at the center of everything in the universe, including humans, trees, rocks, oceans, stars, planets, and even things.

Reconnecting to this place of absolute stillness is not an easy task. In order to find and live from this place of innocence and Pure Being, we must unlearn what we have learned. We must peel away the many layers of adopted beliefs and conditionings. We must transform what is false in us and all the games that our ego plays in order to survive. We must understand that awakening can only happen by with integrity and purity of heart.

Beliefs never lead us to self-discovery. Beliefs keep us ignorant of the universal truth of who we truly are. They keep our energy and consciousness imprisoned in anxiety and false fears about survival.

The easiest way to begin the process of unlearning is first to explore:

What are your beliefs and conditionings; how were they formed; and how can you transform them into consciousness so you can fully live your life and contribute your unique gifts to the world?

Answers to these questions cannot be found with the mind or energy work. Just like a computer program, the mind actually is the generator of the beliefs and cannot see or dis-identify from itself. Only consciousness, which is an integral part of the being, can recognize itself and see what is eternal and indestructible and what is impermanent and finite.

Having worked with thousands of people over the past 25 years, I have discovered a fundamentally new way that helps people access and transform their beliefs (which are not just in the brain but in the entire body) without using the mind. Each person can use this self-healing and self-discovery system on their own, to become self-empowered, to discover what is true and false within them, and to heal into consciousness.

About Mada Dalian

Mada Eliza Dalian is a spiritual teacher, creator of the self-help Dalian Method for adults, teens, and children, and a master trainer of Dalian Method Facilitators and New Paradigm Leaders. She is the award-winning author of In Search of the Miraculous: Healing into Consciousness and Healing the Body & Awakening Consciousness with the Dalian Method: A Self-Healing System, for a New Humanity (book and 2 CD set). For more information, visit www.MadaDalian.com.

Roots and Evolution of Mindfulness

Roots and Evolution of Mindfulness

Before reading this article, listen to a spoken introduction with Joel and Michelle Levey.

When we first began our study, practice, and research of mindfulness in the early 70s, we knew fewer than a handful of people who were involved in this path of practice. As our practice and research matured, we began to develop mindfulness-based programs in medicine, higher education, and business. In the mid-70s and early 80s, we knew of no one else bringing these methods into the mainstream. Gradually over the years, a groundswell of insight, interest, and research has emerged, creating a host of benefits and challenges, clarity and confusion, that inspires and confounds the modern mindfulness movement.

Our intent in composing this brief article is to offer an overview of some key perspectives on mindfulness. For people relatively new to mindfulness, it’s helpful to have a clearer understanding of its roots, shoots, and trends in order to access the deeper meaning, purpose, and value of this vital practice.

To the degree to which we wake up with mindfulness and learn to open our hearts and minds, the walls of our conventional, familiar, consensus view of reality become more clear, open, and transparent, revealing a deeper, vaster, multidimensional, and interrelated view of the actual nature of reality than we have previously imagined. This is why what we call mindfulness meditation is traditionally known as Vipassana, or ‘Insight Meditation.’ Mindfulness gives us access to insight and the direct, non-conceptual intuitive wisdom that liberates us from our misconceptions regarding the nature of reality and the true nature of ourselves.

You Reading This, Be Ready

by William Stafford

Starting here, what do you want to remember?

How sunlight creeps along a shining floor?

What scent of old wood hovers, what softened

sound from outside fills the air?

Will you ever bring a better gift for the world

than the breathing respect that you carry

wherever you go right now? Are you waiting

for time to show you some better thoughts?

When you turn around, starting here, lift this

new glimpse that you found; carry into evening

all that you want from this day. This interval you spent

reading or hearing this, keep it for life—

What can anyone give you greater than now,

starting here, right in this room, when you turn around?

While mindfulness is certainly widely adopted and practiced, our experience is that surprisingly few people are aware of its deep roots and origins in wisdom traditions—its more profound meanings, value, highest implications, and most intriguing applications. Our intent here is to offer insight, inspiration, and illumination on these facets of the jewel of mindfulness as it shines out in our modern times.

Roots of Mindfulness

Mindfulness as a technical term has its historical origins in the ancient Pali word sati used by the Buddha in his teaching on mindfulness over 2600 years ago. Sati literally translates as “memory”- as in remembering what you are paying attention to in the present moment of awareness. In an attempt to meaningfully translate treasured Buddhist meditation manuals, the English translator Rhys Davids was the first to offer an English translation using “mindfulness” in 1881, and, by 1910, mindfulness had become the generally accepted norm. Davids was inspired to use the term “mindfulness” by its use in an Anglican prayer that says, “Always be mindful of the needs of others.” Interestingly, from this initial choice to translate sati as mindfulness, there is an implication that mindfulness is also akin to a newly emerging meme of kindfulness which reminds us that we pay attention to what we care about. The widespread use of the term ‘mindfulness’ has endured to this day where we find the meaning of mindfulness continuing to be adapted, as it is incorporated into common use with an ever expanding variety of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) that are emerging within health science, corporate, and high-performance arenas of contemporary culture.

Unfortunately, the meaning of the term mindfulness also is becoming increasingly misconstrued through its association with deep relaxation without mindful awareness, creative imagination visualizations, getting a good night’s rest, ‘mindfulness chairs,’ mindful men’s clothing, or even mindful mayonnaise—all of which have little or nothing to do with the meditative practice of mindfulness. Some respected teachers in the realm of mindfulness have gone so far as to say that the word ‘mindfulness’ has all but lost its original meaning.

Roots of the Modern Mindfulness Revolution

While the teachings of mindfulness practice have endured for millennia since the time of the Buddha, the contemporary “mindfulness revolution” was propelled into modern times by the colonial thrust of the British Imperial Army invading and conquering the Buddhist kingdom of Burma in November 1885.

For centuries the Burmese people regarded their king as ‘the protector of the Dhamma‘- the liberating teachings of the Buddha which, when taken to heart, have the power to free us of our delusions and confusions by opening our wisdom eyes to directly discern things as they truly are. Mindfulness is the primary practice of these liberating teachings, and its power lies in quieting the conceptual dualistic overlay of thoughts to allow direct insight into the true nature of reality to arise clearly in the mind.

As the Brits marched into the capital city of Mandalay, the Burmese people looked on in horror as their beloved king and his family, surrounded by British soldiers brandishing rifles, were taken from the royal palace and unceremoniously loaded in an oxcart that carried them to a waiting steamship that would carry them into exile. The royal palace was then transformed into an officers’ club for drinking, dancing, and socializing!

A profound wave of concern rippled through Burmese society giving rise to an unprecedented cultural revolution that activated the Burmese people to protect the precious and vulnerable teachings of the Dhamma. Foremost among these cherished teachings was the practice of mindfulness.

Up to this time in Burma and throughout Southeast Asia, the teachings and practice of mindfulness had been mostly held within the monastic community of ordained monks and nuns, while the religious practices of the lay community focused primarily on generosity and giving of alms to generate spiritual merit, with the assumption that lay people were unlikely to actually realize enlightenment through practicing meditation.

With the advent of the British invasion and the king’s exile, visionary teachers within the monastic community, lead by the monk Ledi Sayadaw, and the householder Saya Thetgyi spread the practices of the Vipassana tradition, from which mindfulness is derived, throughout secular society. In the decades that followed, a contemplative cultural revolution spread throughout Southeast Asia giving rise to a renaissance and wide diffusion of mindfulness teachings with both the monastic and lay communities. (Braun, 2014)

Three Main Streams of Mindfulness Practice

The next wave of mindfulness revolutionaries appeared as droves of globe trotting spiritual seekers, peace core volunteers, government spooks, and mind scientists who traveled to Asia in the 1960s and 70s intent on seeking out enlightening teachers, wisdom teachings, and liberating contemplative technologies. Word of inspiring teachers and meditation retreats quickly spread through the social networks of those times drawing early waves of contemplative pilgrims to the monasteries and meditation centers of Southeast Asia to get their first immersive and transformative experiences of intensive mindfulness meditation practices, which were often presented in 10 day silent retreat formats or longer even more intensive retreats.

Through the influence of many of these early adopters of mindfulness, three principle streams of mindfulness practice have flowed into modern Western culture.

Insight Meditation: One stream of mindfulness practice came to the West through the teachings of Mahasi Sayadaw, U Pandita, Ajahn Chah, Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu, and other Thai and Burmese teachers of the “forest monastery” tradition which emphasized a blend of mindful breathing, noting and noticing of the nuances of momentary changing experiences, mindful walking, mindful eating, integrating mindful awareness into every activity, and resting in open clear awareness without grasping at any momentary experience. This lineage of mindfulness practice is widely referred to as “Insight Meditation” and was introduced to the West primarily through the influence of Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberg, and Joseph Goldstein who co-founded the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts in 1975. Kornfield later also co-founded the Spirit Rock in Marin, California in 1988 with a number of other teachers.

The wise and creative teachings offered at these two centers alone have inspired tens of thousands of people over the past 40+ years, giving rise to hundreds of other practice centers around the globe, and playing a significant role in inspiring the global diffusion of mindfulness practice into higher education, medicine, business, military, government, sports, and other arenas of modern life. Within this stream many other respected teachers, including Anagarika Munindra, Dipama, Ajahn Amaro, Ajahn Sumedho, Thannasaro Bhikkhu, Taungpulu Sayadaw, and Dr. Rina Sircar, to name but a few, have deeply inspired the diffusion of mindfulness teachings throughout North America, UK, and Europe.

Vedana Vipassana: The second stream came to the West from the Burmese teacher U Ba Khin, the Accountant General of Burma, who founded the International Meditation Society in Rangoon in 1952 where he attracted the attention of many international students and teachers. As a lay practitioner and respected lineage holder from Saya Thetgyi of the vedana vipassana tradition of mindfulness practice, and also a respected accountant, U Ba Khin accepted the invitation from the Burmese government to assume the role of Accountant General and to assume leadership in order to route out the corruption in the Burmese Treasury Department. U Ba Khin accepted this appointment with two conditions. First was that one wing of the Treasury Department would be transformed into a meditation hall where members of his staff could come and meditate at any time. Second, was that everyone on his staff in the Treasury Department would train with him and participate in at least one intensive ten-day silent Vipassana style mindfulness retreat. As U Ba Khin said, “I refuse to work with incompetence.”

U Ba Khin’s style of mindfulness practice focused on developing concentration through single-pointed concentration on the breath, and then the close application of mindfulness by scanning or “sweeping” mindful awareness slowly through the body from the top of the head to the toes, over and over again, for up to 20 hours per day, leading to a profound state of vivid mental clarity and the purification of embedded congestion within the gross and subtle body. In this austere and intensive style of practice there is only sitting meditation, with no mindful walking, yoga, mindful eating or other practices at all.

In his later life, U Ba Khin passed his legacy of teachings on to seven teachers including S.N. Goenka (a Burmese businessman who is widely known in the West), Robert Hover (a former U.S. aeronautical engineer), Ruth Denison (a German pioneer in embodied movement practices), and John Coleman (a former British MI6 agent), all of whom carried these liberating teachings back to North America and Europe and around the globe. In particular, Goenka’s approach to teaching mindfulness has become very popular and widely available in the West and around the world, especially as the teachings and retreats are offered free of charge. After retreats, the students are encouraged to make donations and “play it forward” to freely fund retreats for future students.

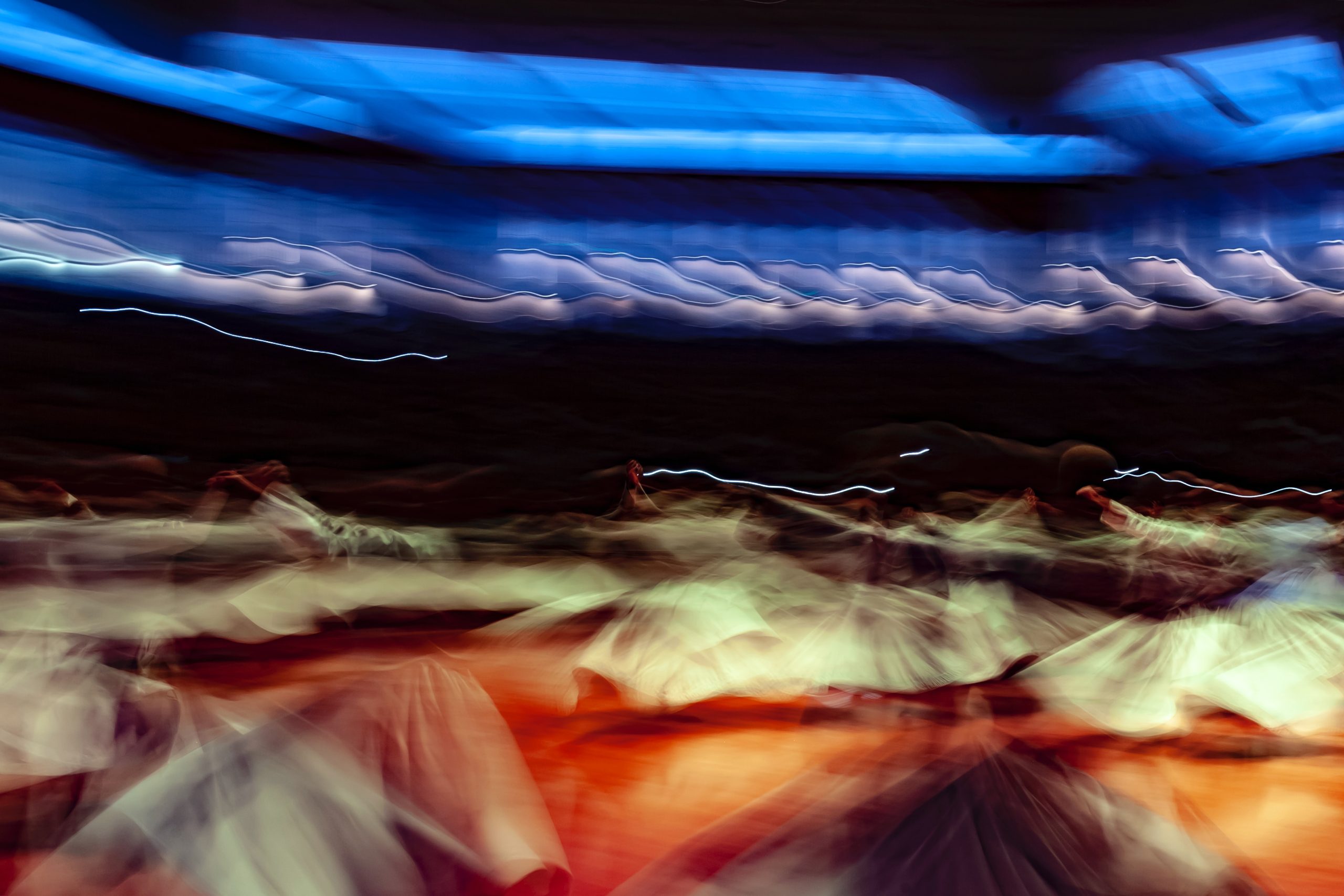

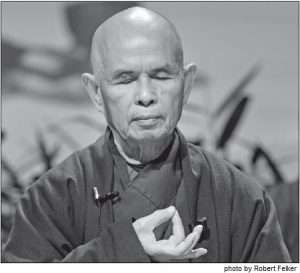

The Order of Interbeing: A third stream of mindfulness teachings came to the West in part due to the U.S. invasion of Vietnam, where the monk Thích Nhất Hạnh and his community were practicing and teaching mindfulness as an integral practice in their non-violent peace work amidst the terrors of the war. As the war raged on and many of his colleagues were brutally murdered, Thay, as his students call him, took refuge in France where he founded the Plum Village international Meditation Center and the Order of Interbeing. There, he continued to teach his unique and highly accessible form of mindfulness which emphasizes the practice of mindful breathing, mindful walking, and the repetition of meditation phrases or gathas, synchronized with inhalation and exhalation. To develop deeper ease and continuity of meditation, words such as calming, smiling and arriving are used to help relax and focus the mind and quell the tendency toward discursive thoughts during meditation practice. Today there are hundreds of centers around the globe teaching Thay’s style of mindfulness practice.

One of Thay’s gifts is his encouragement to bring a gentle, heartfelt, compassionate inner smile to mindfulness practice,—“smiling to our sorrow”—in order to realize that “we are more than our sorrow.” This practice of gentle smiling has influenced mindfulness instruction and how it is often introduced and practiced in the West. Most importantly, his teachings on interbeing—the interconnection of all Life—and the illusion of a ‘separate self’ are fundamental for those who follow this teacher.

Beyond these three primary streams, there are other streams, lineages, and teachers who emphasize a variety of aspects or approaches to the practice, and there are also many teachers and centers that weave together teachings and practices drawn from these different traditions.

Kindfulness | Mindfulness Blossoms As Compassion and Lovingkindness

Being present with kindness and compassion

is being mindful.

– Jon Kabat Zinn

As the practice of mindfulness deepens and matures, it embraces and is responsive to the needs, not only of ourselves, but of all beings who suffer and experience vulnerability or injustice in their lives, society, and world. As many of the foremost Western mindfulness teachers have matured in their practice, the nature and tone of their teachings have warmed, shifting from a more austere focus on “bare attention” and taking on a more compassionate tone that encourages their students to blend mindful awareness with a merciful, warm hearted approach to their mindfulness practice.

It is becoming increasingly more common for mindfulness teachers to expand their studies and practice of mindfulness to draw inspiration from traditions that give greater emphasis to heartfelt qualities such as gratitude, genuine friendliness, compassion, lovingkindness, self-compassion, and engaged social justice action, into mindfulness education and training. This heartwarming, compassionate impulse may be integrated into mindfulness practice simply as a gentle, merciful, inner smile as one musters the courage to look within and mindfully, whole-heartedly embrace the tension, apprehension, sadness or rage found there. Or it may be intentionally cultivated as a robust practice of meditation such as lovingkindness—or metta—wishing well to ourselves, others, and all beings; or generating radiant compassion regarding and embracing the presence of suffering in our lives, relationships, and world; or activating an explicit dedication to practicing mindfulness with an intention of realizing one’s true nature and highest potentials for the benefit of all beings.

As mindfulness matures into kindfulness (Braum, A. 2016), on a societal level, we are witnessing the emergence of more university programs that explicitly include compassion science and encourage compassion-based practices as part of their curriculums. Among the most respected programs in today’s world are:

Stanford University’s CCARE Program- Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education http://ccare.stanford.edu);

Mindful Self Compassion- self-compassion.org/the-program/

The Greater Good Science Center- connected with Stanford and UC Berkeley http://greatergood.berkeley.edu

University of Wisconsin’s Center for Healthy Minds- (http://www.investigatinghealthyminds.org/cihmDrDavidson.html);

Mind and Life Institute- https://www.mindandlife.org/

Max Planck Institute’s Human Cognitive and Brain Science- ReSource Program (https://www.resource-project.org/en/home.html )

Mindfulness, Collective Intuitive Wisdom, & Human Flourishing

The world we have made as a result of the level of the thinking we have done thus far creates problems that we cannot solve at the same level of thinking (i.e. consciousness) at which we have created them… We shall require a substantially new manner of thinking if humankind is to survive. – Albert Einstein

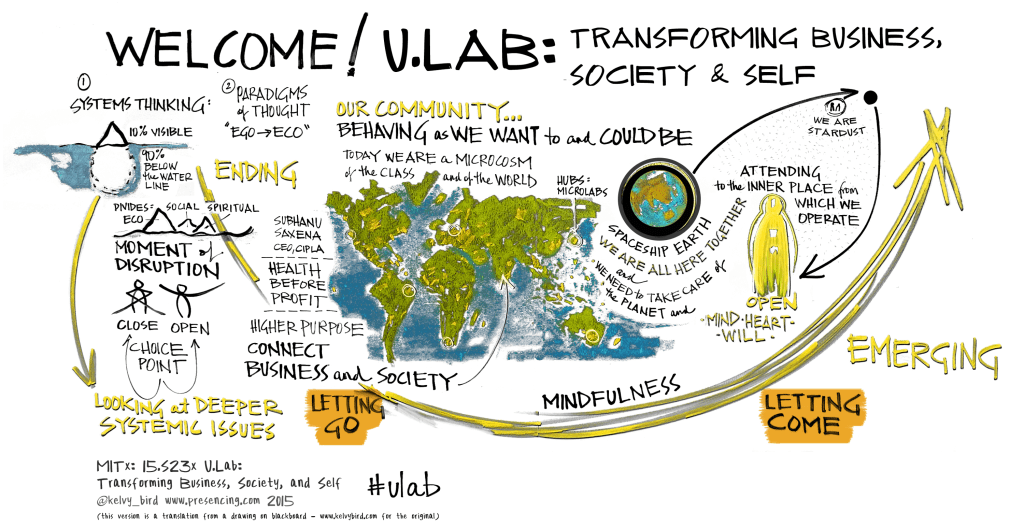

Could it be that the global surge of interest in mindfulness is an evolutionary impulse perfectly responsive to the challenges of these times? From our many years of practice, research, and work bringing mindfulness to organizations and communities around the globe, it seems that the greatest value and most highly leveraged application of mindfulness may be to follow Einstein’s advice. How? By equipping individuals and innovation teams with the skills necessary to refine the level of their personal and collective consciousness in order to access the deeper intuitive wisdom necessary to bring forth breakthrough solutions to complex global problems.

As the key to accessing the most-subtle dimensions of intuitive wisdom, the greatest value of mindfulness in this age may be in its capacity to liberate us from our collective ignorance by opening our minds to the wisdom we need to flourish together in this beautiful and fragile world.

One of our most cherished visions and aspirations is to develop cohorts of altruistically motivated, sincere and disciplined individuals and teams, intent on employing mindfulness for accessing or “sourcing” insight from deeper, subtler strata of personal and collective intuitive wisdom. This is in order to bring forth the insights and innovations necessary to resolve the dire challenges of these treacherous times, while promoting human flourishing and thriving for generations to come. (Levey, J. and Levey, M. 2008)

Mainstreaming Mindfulness: Encouraging Trends

In our work and travels with hundreds of leading medical centers, universities, organizations, and governmental groups around the globe over the past 40+ years we are heartened to see an ever widening diffusion of mindfulness teachings. Here are some of the most inspiring examples we have seen:

- Contemplative Science: The rapidly emerging field of contemplative science brings together the best of technology, neuroscience, and inner technology inspired by the wealth of the world’s wisdom traditions giving rise to innovative programs and research in hundreds of universities and respected institutes around the globe. Mind and Life Institute’s International Symposiums on Contemplative Studies have brought together thousands of people from around the world to share their research on mindfulness and many other contemplative practices. (https://www.imconsortium.org)

- Leadership and Contemplative Science: While a myriad of leadership developments are being offered in our world today, few have seriously addressed the development of moral, ethical, and contemplative capacities of leaders. One of the most relevant and inspiring initiatives we have seen in this regard is the Mind and Life Institute’s Academy for Contemplative and Ethical Leadership (ACEL) that we were fortunate to help birth. (https://www.mindandlife.org/legacy-programs/acel/ )The ACEL charter states,

- Mindful Law: Nearly a decade ago Rhonda McGee took a bold step to introduce the first course on Mindfulness in Law class at Berkeley Law School. Since then, 40+ law schools have followed her lead with programs on Mindfulness and Contemplative Lawyering as essential skills for professionals in the judicial system.

- Mindfulness in Medicine: Mindfulness is an essential element of the core curriculum within the 70+ medical schools that participate in the Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine.https://www.imconsortium.org

- Mindfulness in Government: In recent years, British Parliament’s Mindfulness Roundtable which involved over 120 MPs and Lords from different parties of the government who have trained in mindfulness, gave rise to the development of the Mindfulness Initiative and the Mindful Nation UK Report which encourages the integration of mindfulness in four domains of British society: health care, education, criminal justice, and the workplace. (The Mindfulness Initiative: Mindful Nation UK Report. 2015)

- Wisdom 2.0: Since its inception in 2010, the Wisdom 2.0 conferences have brought together thousands of organizational leaders and consultants from around the planet interested in the interphase of mindfulness, meditation, yoga, leadership, innovation, organizational health and performance, social justice, quality of life, and bottom-line business results. With leaders and presenters from Google, Ford, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, PayPal, Zappos, AETNA, Blackrock, Burning Man, Slack, British Parliament, U.S. Congress, and many other leading organizations to explore the many wise and helpful ways that mindfulness and related practices is delivering measurable value in our lives and world of work. (http://wisdom2conference.com/About)

- Mindful Social and Emotional Learning (SEL): With an ever increasing wealth of affirming data, robust programs are integrating mindfulness with social and emotional learning into a wide array of primary and early childhood development learning programs around the globe.

For a monthly update of compelling research on mindfulness and mindfulness based practices visit: http://GoAMRA.org

These are just a sampling of the significant and inspiring trends that we are seeing in the diffusion of mindfulness into the mainstream mindstream of our world.

References

American Mindfulness Research Association, http://GoAMRA.org

Bodhi, B. 2016. The Transformations of Mindfulness. Published in Handbook of Mindfulness: Culture, Context, and Social Engagement (Mindfulness in Behavioral Health). Edited by Ronald E. Purser, David Forbes and Adam Burke. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2016 https://books.google.com/books?id=nBFVDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=The+Transformations+of+Mindfulness.+Published+in+Handbook+of+Mindfulness:+Culture,+Context,+and+Social+Engagement+(Mindfulness+in+Behavioral+Health).+Edited+by+Ronald+E.+Purser,+David+Forbes+and+Adam+Burke.+Springer+International+Publishing,+Switzerland,+2016&source=bl&ots=Yh334UtV40&sig=HA4UeflyHZbsU9OCjYGTMouD1LI&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiZ1vqN3e_ZAhUB24MKHW_dB98Q6AEILzAC#v=onepage&q=The%20Transformations%20of%20Mindfulness.%20Published%20in%20Handbook%20of%20Mindfulness%3A%20Culture%2C%20Context%2C%20and%20Social%20Engagement%20(Mindfulness%20in%20Behavioral%20Health).%20Edited%20by%20Ronald%20E.%20Purser%2C%20David%20Forbes%20and%20Adam%20Burke.%20Springer%20International%20Publishing%2C%20Switzerland%2C%202016&f=false

Bhikkhu, T. 2012. Right Mindfulness.

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/thanissaro/rightmindfulness.pdf

Braum, A. 2016. Kindfulness. Wisdom Publications.

Braun, E., Spring 2014. “Meditation En Masse: How Colonialism Sparked the Global Vipassana Movement” Tricycle. http://www.tricycle.com/feature/meditation-en-masse

Clarke T. C., et al. 2015. “Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults: United States, 2002–2012,” National Health Statistics, No. 79, Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics, 2015; “Uses of Complementary Health Approaches in the U.S.,” National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine. https://www.imconsortium.org

Gyatso, T. the Dalai Lama. 2001. Dzogchen: The Heart Essence of the Great Perfection. Snow Lion Publications.

https://books.google.com/books?id=4HqLxJRN6MUC&pg=PA254&lpg=PA254&dq=%22dalai+lama%22+Dzogchen+London&source=bl&ots=uKMkzDoubE&sig=j0UcaRAuBVMBTXSju5kDod–hzo&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwizhNa_w5HWAhVBwWMKHQBKA1MQ6AEITDAG#v=onepage&q=%22dalai%20lama%22%20Dzogchen%20London&f=false

Kotler, S. and Wheal, J,. 2016. Stealing Fire: How Silicon Valley, the Navy SEALs, and Maverick Scientists Are Revolutionizing the Way We Live and Work. HarperCollins.

Levey, J. and Levey, M. 2015. Living in Balance: A Mindful Guide for Thriving in a Complex World. Divine Arts. https://divineartsmedia.com/products/living-in-balance-a-mindful-guide-for-thriving-in-a-complex-world

Levey, J. and Levey, M. 2008. Mind Treasure. Intuition at Work. Sterling Stone Publishers.

Mind and Life Institute ACEL (Academy for Contemplative and Ethical Leadership). 2015. https://www.mindandlife.org/legacy-programs/acel/

Mind and Life Institute—Contemplative Science Symposiums. https://www.mindandlife.org/international-symposium-for-contemplative-research/

The Mindfulness Initiative: Mindful Nation UK Report. 2015. http://www.themindfulnessinitiative.org.uk/publications/mindful-nation-uk-report and http://www.themindfulnessinitiative.org.uk

Mingyur, Y. Rinpoche, and Tworkov, H. 2014. Turning Confusion into Clarity: A Guide to the Foundation Practices of Tibetan Buddhism (Boston: Snow Lion, 2014).

National Business Group on Health and Fidelity, July 14, 2016. Corporate Mindfulness Programs Grow in Popularity.

Pinsker, J. March 10, 2015. Corporations’ Newest Productivity Hack: Meditation. Atlantic.

Purser, R., Milillo, J. 12 May 2014. Mindfulness Revisited: A Buddhist Based Conceptualization. Journal of Management Inquiry. https://www.academia.edu/8102895/Mindfulness_Revisited_A_Buddhist-Based_Conceptualization

Purser, R., Ng, E., & Walsh, Z. (2018). The promise and perils of corporate mindfulness. In Chris Mabey and David Knights (Eds.), Leadership Matters: Finding Voice, Connection and Meaning in the 21st Century (pp. 47-63). New York, NY: Routledge.

Thubten, A. 2012. The Magic of Awareness. https://books.google.com/books?id=tJofqSlqmsYC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Anam+Thubten+Thubten+magic+of+awareness&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjpl5bixJHWAhVD1WMKHb7EAYwQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=Anam%20Thubten%20Thubten%20magic%20of%20awareness&f=false

Wieczner, J. March 12, 2016. Meditation Has Become a Billion-Dollar Business. Fortune.

Wisdom 2.0, http://wisdom2conference.com/About

About Joel and Michelle Levey

Dr. Joel and Michelle Levey, founders of Wisdom at Work, are regarded as leaders and early pioneers in the global “mindfulness revolution,” the “contemplative science,” and the “collective wisdom” movements. Their inspired wisdom at work demonstrates the profound sensibility of integrating contemplative science, interpersonal neurobiology, and contemporary mind-fitness training for developing the extraordinary capacities of leaders, teams, and organizations in these complex modern times. Learn more here.

Presence at the Edge of Our Practice

Presence at the Edge of Our Practice

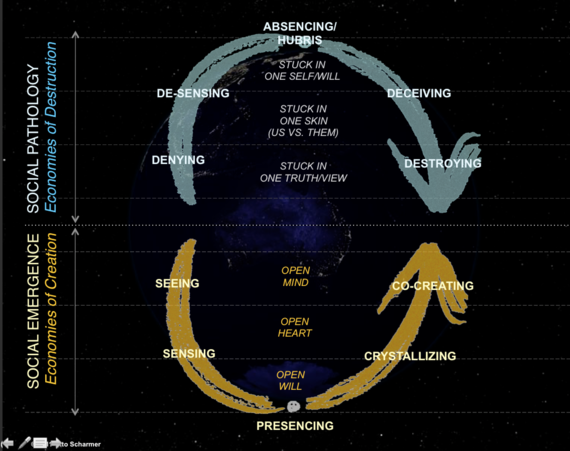

Humanity is in a time of transition, one that we can navigate successfully only with a shift in consciousness. How can we wake up from the collective neuroses that have driven our civilization into decadence and decline? How do we recover from the addictions that hold us in their thrall? In this article, I propose the perspective of practice as a pathway to liberation from destructive and reductive habits that is accessible to all and offer a preliminary overview of human practices for the 21st century.

One of the most potent invocations ever uttered by humans has to be the famous Chinese curse (and blessing) “May you live in interesting times.” No doubt, the times we are living in are hair-raisingly interesting and getting more so by the day. So much so that we really don’t know whether we—humanity as a species—are going to survive them. The dangers facing us and our fellow sojourners on ‘Space-Being Earth’ are by now so well known that I prefer not to dwell on them, saving space instead for unpacking more edifying ideas. Starting with the Good News.

This News is not new. We have instinctively and experientially known it, literally, forever—since the dawn of homo anything. Namely, that the Cosmos is a living, sentient entity of indescribable radiance, magnificence and numinosity, in which we participate as an inextricably entangled component, along with all of the rest of life (including that which we thoughtlessly assume to be inanimate). We knew this, however, back in the days when we still lived immersed in the oceanic womb of the Great Mother. That was before the evolutionary process ripped our consciousness free of its matrix (our expulsion from the ‘Garden of Eden’) and placed us in a relationship to the rest of life which has become pathological: in our newly self-conscious state, we succumbed to the urge to subjugate and control nature, in constant terror of being sucked back into the maw of unconsciousness and ‘barbarism.’[1]

For the past 5000 years or so, we- particularly in the Western world and all those places under the thrall of the Abrahamic religions[2]- have chosen to forget this knowledge of the inextricable Oneness of all things in favor of an absolute belief in the supremacy of man over nature, man over woman, mind over matter, reason over emotion. These days, the human rational intellect still assumes it reigns supreme, repressing and denying instinct and unconsciously projecting the repressed elements of the human psyche (both individual and collective) onto ‘the other.’ Herein lies our supreme peril. Few voices have articulated it more clearly or prophetically than Carl Gustav Jung, back in the first half of the 20th century. Jung recognized and warned of the danger—one that our civilization is still quite oblivious to—presented by the growing dissociation of the conscious ego from what he called the primordial or instinctual soul. He saw that the more we emphasized reason and the supremacy of the rational mind, the greater the danger that instinct—whose power we have failed to acknowledge or understand—would drive, possess, delude and overwhelm us, and the more we would fall victim to ideologies and utopian goals which could ultimately lead us to destroy ourselves.[3]

This danger springs from the failure to recognize and acknowledge that the conscious, rational mind of the human being, in both its individual and collective/cultural manifestations, sits like a lily pad atop a caldera of unconscious psychic material that is both unfathomably immense and inconceivably powerful. Our dawning understanding of the universe as a holographic phenomenon indicates that matter, energy, space, and time are not primary, as we have tended to assume. Rather, these are all different expressions of information.[4] One ramification of this is that the visible world is not the only dimension that is fully interconnected. The human conscious mind is a very, very thin, terrifyingly fragile layer of self-reflexive awareness that floats atop the species memories not only of homo everything, but of every single form of life (animal, vegetable, and mineral) that has evolved over the lifetime of planet Earth. We are talking here about the psychic imprints of patterns of behaviour that have endured for spans of time ranging from millennia to hundreds of millions of years. Habits, with a capital H.

We can perhaps most readily relate to this phenomenon through personal experience with our very own ‘triune’ brains. The reptilian brain has been around for some 500 million years, the mammalian brain for 200 million; the neocortical brain is the baby of the family, at around 1 million years. Not surprisingly, given hierarchy of age, the primordial reflexes governed by the older brain systems have far more influence on the neocortical brain than it has on them. How many times a day, in our stress-filled daily lives, are we drenched in adrenaline and cortisol as our instinctive fight-flight mechanism is triggered by a minor irritation or momentary overwhelm, even when there is no real danger in sight, and hasn’t been for years? Have you ever been swimming in the sea, glimpsed a shadow beneath you, and been instantly engulfed in primal terror of being devoured by a leviathan from the deep (and it was only a patch of seaweed…)? You were experiencing the millions-of-years-old programming of predator and prey. To quote Anne Baring:

Because these archaic instincts function at a deeply unconscious level we, who see ourselves as the summit of creation, may nevertheless be influenced, even controlled by habits formed during pre-human or early human phases of evolution. Fear of becoming prey can swiftly transform us into predators.[5]

While the neocortex has given us the capacity to reflect when we are confronted with a perceived threat, to allow ourselves time to decide how to respond, it is very rare that we actually do so. The reptilian brain springs into action so much faster than the neocortex! For all our amazing achievements as a species, we remain woefully clueless—as individuals and in most of the world’s surviving cultures—about our own psychology. As we go about our daily lives, we are for the most part blissfully unaware of the projections, assumptions, judgements, and inflations that we continually overlay on everything our senses encounter that we experience as ‘not me.’ The ramifications of this in the collective arena offer special cause for concern. As a result of our rather bloody history since the dawn of aforementioned self-reflective awareness (that history itself a reflection of this mechanism), the drive to conquer and control others before they conquer and control us has become embedded in instinctive patterns of response (a.k.a., habits) that, if we only stop to look, we can see everywhere around us in our modern society—especially and, most alarmingly, in our politics, economy, religion, and armed forces. What Jung prophesied has indeed come to pass, and we are not even aware of it. Mass insanity didn’t just break out during the World Wars, in Stalin’s Russia, in Rwanda, in Bosnia… It is happening all around us here and now. What else can explain our indifference to the starvation of children and our incapacity to care enough about the despoliation of our beautiful planetary home to come to our collective senses and stop it? Our species has effectively been collectively possessed by the will to power of the more shadowy aspects of what Jung named the collective unconscious.

So here we are. On the one hand, we have the intellectual understanding, backed up by compelling scientific evidence, of the sublime oneness of creation, and the potential that this opens up for an enlightened human culture and civilization. On the other, we are literally surrounded by the bleak evidence of the power of the instinctual trauma that has our entire civilization so thoroughly in its grip that we are careening toward destruction without any capacity to engage our conscious will and change course. Many are the voices that proclaim impending salvation—sometimes for the chosen few (the ‘rapture’) and sometimes for all humanity (our comfortable conviction that technology will save us at the eleventh hour). And yet here we still are, contending with ever more extreme polarization, violent conflict, and existential threat, all amped up by the machinations of power-hungry politicians and profit-hungry corporations, and the fear-mongering of the mainstream media channels that so firmly anchor the collective attention on the worst in human nature. To deaden the pain of such horror, the current mainstream practice is to seek distraction in addiction, be it to mind and mood altering substances, to work, to entertainment, to the acquisition and consumption of material goods…our addictions are legion!

Please note my choice, in the previous sentence, of the word practice. If salvation there be for the human race, I believe it lies in the humble notion of practice. The Oxford English dictionary offers three definitions of the term:

(1) the actual application or use of an idea, belief, or method, as opposed to theories relating to it (synonyms: application, use)

(2) the customary, habitual, or expected procedure or way of doing of something (synonym: custom)

(3) repeated exercise in or performance of an activity or skill so as to acquire or maintain proficiency in it (synonym: training)

In the sentence at hand, the operative definition is (2). Revisiting my assessment of the peril and the promise that beset us in these days, the unconscious trance state currently driving us over the cliff is maintained through the cultural, social, and economic customs of Western civilization as they spread across the globe.

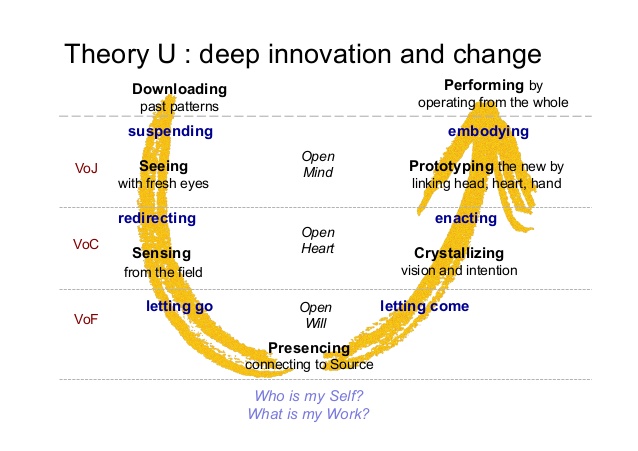

The bridge to the “More Beautiful World our hearts know is possible”[6] lies in actually applying the best of human knowledge- all that we know to be true about depth psychology, healthy living, wise governance, nurturing and empowering education, regenerative farming, and so on (definition 1); through persistent, repeated, intentional individual and collective exercise in the requisite methods until we acquire proficiency in them (definition 3). This is how old habits (definition 2) are broken and new ones instilled. This is how we move from our current preconscious state toward becoming a species composed of awake, aware, responsive and responsible, self-actualized, and unique individuals who also have developed a capacity to participate in the collective consciousness that, too, is part of our potential as humans.[7]

I see practice, then, as a royal road to manifesting a balanced and healthy new paradigm in our culture- a bridge to liberation from so much of what ails us. When we first come to practice, or are invited to experience the practices of others, these often feel unfamiliar, uncomfortable and unnatural. That’s not surprising: their whole purpose is to break old habits and instill new ones that help us to experience and embody a very different evolutionary trajectory for homo sapiens—beyond mere dreams of peaceful coexistence—as healthy and generative participants in the dance of life on Earth.

This focus on practice is one of the hallmarks of the emergent exemplars of what I call Aquarian Patterns (patterns underlying the embryonic new civilization). It is an immensely rich and complex domain and, in this article, I must content myself with giving a preliminary overview. As I sense into these patterns in my own life and experience (something I have been doing for over 20 years now), the framework that has given me the broadest and most explicit practical overview of the potential offered by intentional practice is the ‘Fourfold Practice’ that describes the DNA of the Art of Hosting Conversations that Matter.[8] I feel that this is a particularly fruitful domain to offer as an example of practice because it concerns the art of being together in a generative and co-creative way, one which can hold us well in our interactions as we apply all the other practices needed to build the ark of a new civilization where all life can thrive.

The Stance of the Practitioner

My rather intense engagement with the practices of the Art of Hosting and its community of practitioners over the past 12 years has brought me to recognize the power and potential of the ‘stance of the practitioner:’ practice is not a boring chore, but a sacred troth—a commitment to ourselves, to those we serve by hosting them, to each other as a community of practice, to the world at large, and to the practices themselves. Stepping from the autopilot of everyday consciousness into practice is like stepping into the dojo of the martial arts. We leave our shoes (and socks!) at the door and as we step onto the mat, we bow to the practice, to the teachers, and to our fellow practitioners. Whatever the field of practice, this is Sacred Space and we are in Sacred Work together.

The Fourfold Practice[9] is so named for its four ‘domains’ of practice: the inner practices of ‘hosting the self into presence’; the relational practices of ‘participating and being hosted’; the leadership practices of ‘hosting others in conversations that invite presence’; and the collective practices of ‘co-creating in community.’ All four of these domains of practice are based on the core practice of ‘holding space’—an active, energetic process of deep presence, listening, and mindfulness that is at the heart of intentional manifestation. All four also are firmly rooted in the ground of continual learning, both individual and collective. There is no end to what becomes possible if we stay open and humble enough to keep learning!

Unpacking each of these domains, we can see that there is such a great variety of practices that no one need go hungry. Living a healthy and balanced life means adopting a variety of practices in each of these domains. The idea is not to bolt these practices onto our daily lives as extra things to do (the last thing we need is more busyness!), but rather to shift our lives gradually until we live them through our practices.

Hosting the Self into Presence

Living well in a participatory universe is the art of being. Being requires presence—that quality of authenticity, vulnerability, confidence, and courage, which comes from deep personal work that cannot be done in isolation. Presence is a holistic, emergent quality incorporating physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual dimensions. Presence is what allows us to stand in the midst of intense emotion, to tolerate chaos without rushing to fix anything, to be comfortable with the silence and stillness of non-doing, to work in service of a purpose bigger than personal ego.

Hosting self is the practice domain of holding space for the emergence of presence. On a physical level, it involves listening to your body, nourishing it with pure, clean, natural food and water, getting adequate rest and exercise, and managing stress. On a mental level, it cultivates an open mind free of habitual patterns of thinking and unconscious beliefs and assumptions. On an emotional level, it learns to recognize what triggers habitual emotional reactions, heal the underlying trauma and develop new ways of embodying and expressing emotion in general. It also helps us to own our expectations and projections and to cope with anxiety and uncertainty. It nurtures self-compassion and a willingness to take risks, and it enables us to be comfortable with so-called mistakes and failures and learn from them. On a spiritual level, hosting oneself connects us with the unseen world of energy and spirit, reduces attachment to ego, and frees us to work through the heart with compassion and without the need to be in control. It supports us in embracing solitude and silence and a connection to the natural world. Presence cannot be manufactured or forced, or even developed. It is the natural emergent quality available when we gently recognize and remove barriers in a self-reinforcing cycle of holding space for presence which allows for deeper holding of space and deeper presence.

There is no set of specific approved or recommended practices for hosting oneself. Every practitioner must find his/her own practices for letting go of control and holding space for presence to emerge. These practices could include yoga, dance, martial arts, meditation, contemplative writing, prayer, psychotherapy, time in nature, solitude, tantric sex, art, music… the list is endless. The importance is finding a set of practices that increase your personal capacity for presence and then to commit to regular practice. We have found it most helpful to ground any and all practice in an inner state of gratitude, awe, curiosity, and love.

Participating and Being Hosted

With the presence which arises from hosting the self, we are ready to participate. On one level, this means engaging in activities with others and allowing yourself to be led. As your practice of participating deepens, it can evolve into a participation with all of life. At that level, participation becomes an intense immersion in what is, without expectations and without a desire to attain any particular outcome. It is about showing up with your full self and your own interests and predilections whilst sensing what wants to happen and discerning how to align yourself and your interests in service of a larger purpose. Participating fully requires trust and letting go of control. It invites a depth of communion in which silence is a welcome participant and in which connection and communication transcend spoken words and include nonverbal and energetic components. Participation is an invitation into the unknown, an opening to being changed, a willingness to step into the field from which emergence is possible.

In human society, participation frequently manifests through conversation[10], and conversation is an art. It is not just talk. It demands the presence to listen carefully to one another, to nature, and to the unseen. It demands silence as well as words. It demands that we offer what we can in service of the whole, speaking with deep intention while listening with rapt attention. Life-affirming participation flows from a mood of curiosity, recognising that curiosity and judgment cannot live together in the same space. If we are judging what we are hearing we cannot be curious about the outcome, and it will be difficult for the conversation to move beyond defending preconceived positions. Skillful participation in conversation requires an open mind, open heart, and open will. It calls for mindfulness and the ability to slow a conversation down to allow deeper listening and clarity to arise.

Practices within the domain of participation include active listening; dialogue; asking powerful questions; owning one’s own projections, expectations and assumptions; clarifying intentions; cultivating a mood of curiosity and openness and listening to nature. It is clear at a glance that many of these practices are a complex world in themselves- there is no danger of getting bored!

Hosting Others into Presence

As we transition from the prevailing paradigm of the ‘leader as hero’ to the emerging ‘peer-to-peer’ paradigm, the conversational ‘leader as host’[11] creates and holds a container in which people can do their best work together. This holding of space involves sensing the conditions that will allow a group to settle into collective presence, holding that space through chaos so that new order and clarity can emerge. Such conversations do not just happen, they are the product of clear intentions, a powerful calling question, a compelling invitation, good design, skillful framing of the context and the holding of space in which the work can be done, and, most of all, the presence to hold space for emergence. All of these are practices and skills of hosting conversations.

Initially, hosting is likely to consist of mastering a set of core methodologies.[12] In time, the practice calls for increasing depth of presence to be able to hold space for deeper or more challenging conversation. As our capacity deepens, the practice also includes more subtle aspects including preparation of the physical space; invitation and welcoming; and working with the energy of the group. While much of the attention of hosting is focused on the external work—the actions—an equally important aspect of hosting practice is to attend to one’s inner state and learning. Hosting inevitably challenges us at our growing edge, whether that lies in relinquishing control, feeling competent and adequate as a member of a hosting team (hosts are admonished never to work alone!), finding the right language to invite deeper participation, or accessing the courage to touch in on the collective wounds often festering under the surface. A practitioner of hosting is engaged in both the internal and external practices. While very few practices are best done alone (even meditation benefits from a collective field), it is particularly important to work in a team when hosting.

Co-creating in Community

It is one thing to learn new skills and practices in an environment specifically designed to be conducive to learning. But what then? In order to be able apply our learning in our daily lives, to sustain our learning and keep our practice alive and growing, we need to stay connected to other practitioners. The traditional way of addressing such challenges is to create an organisation or association and to follow the wisdom of the experts. But in a context of emergent social transformation, this approach doesn’t work. The shared knowledge springs from collaboration and conversation, and is not in the possession of an expert. There are no rules, no formulae, no formal requirements for doing this work. Life is inviting us to innovate, to collaborate, to discover new models and processes that can serve humanity in our collective journey into the unknown future. Yet there also is a need to recognize and protect the essential DNA of any novel body of work that develops a community of practitioners—there is a constant danger that the practice will be sucked into the miasma of old habits and warped out of shape by prevailing thought forms. Each one of us can benefit from learning from practitioners with more experience and deeper realization. What guidelines and agreements can help a community of practitioners to participate together?

The Art of Hosting community can be illustrative of how such communities can emerge. Over a span of 20 years, it has grown from a few friends sharing ideas together, to a globe-spanning self-organising network with over ten thousand members and a steadily evolving core body of practice accessible to all. This has unfolded, quite deliberately, without any licensing or copyrighting, without any organisational structure, staff or headquarters, without any specific financial expectations or agreements, and without any explicit governance. Over time, a group of more experienced practitioners has emerged who are recognized as stewarding the DNA of these practices, and practitioners come together periodically at open gatherings (one of our guidelines is “whoever shows up are the right people”[13]) to sense into the needs of the community and make any necessary collective decisions. Newer practitioners are encouraged to apprentice to the more experienced and one of the few ‘rules’ within the community of practice is that there needs to be a ‘steward’ involved in any Art of Hosting training. This has provided a framework in which practitioners can learn and develop their capacity while also protecting the deeper patterns and essence of our shared practice. What has also emerged is an online platform for communicating and for collecting and disseminating learning, models, materials, and other artifacts of our learning.

This community of practice pattern has emerged regionally throughout the world in response to local needs and circumstances, and while it doesn’t look the same everywhere, there are many shared elements. The beauty of this fourth domain of practice is that we are all learning together to hold the space for learning together, and for the ongoing emergence of our practices in response to the needs of our changing world. Like so much within the Art of Hosting, this is fractal. The success of our community lies in our systematic engagement with our practices in all four domains. As we learn together, we also are confronted with our blind spots and those parts of our practice that are less skillful or conscious. This provides an opportunity for us individually and collectively to increase our capacity through hosting ourselves. Thus, the Fourfold Practice is an iterative cycle leading to deeper practice and ever-increasing capacity.

In conclusion, my sense is that the practices which will best help us navigate the growing complexity of these transitional times are grounded in the heart. It is the instinctive intelligence of the heart that most thoroughly connects us to ourselves, each other, and all that is. Let us share the core practice of inhabiting the gentle energy of heart-centred awareness as we step into the dojo of our lives. Let us do so in the understanding that this is not the culmination of our journey; rather, it is simply the work that is needed to reach the starting point for the next great adventure: developing our capacity to consciously and intentionally participate in the cosmic processes of co-creative manifestation. This calls for clearing away the debris and drama of our collective ‘story so far,’ learning through heartfelt practice to process and, hence, traverse our existential fears, thereby restoring for ourselves a soul space in which to choose other ways of being, other paths into a future of utterly astonishing potential.

About Helen Titchen Beeth

Helen Titchen Beeth lives in the countryside in Flanders (Belgium). She is a lover of wild nature and mother of twins.

References

[1] This understanding/interpretation is based on the ‘mainstream’ assumptions about the history of homo sapiens. Less widely-known evidence suggests that an earlier global high civilization was wiped out by a cataclysm some 11, 500 years ago, which imprinted massive trauma into our species memory. Barbara Hand Clow, Awakening the Planetary Mind (2011).

[2] With the strong exception of the mystical strands of those religions!

[3] Adapted from The Dream of the Cosmos, by Anne Baring. Archive Publishing, 2013.

[4] The Cosmic Hologram, Jude Currivan. Inner Traditions, 2017.

[5] The Dream of the Cosmos, Anne Baring.

[6] Grateful to Charles Eisenstein for this powerfully evocative phrase.

[7] See also the series of Kosmos articles (2012-13) on Collective Presencing co-authored with Ria Baeck.

[8] See my article in the 2016 spring/summer edition of Kosmos Journal.

[9] This section on the Fourfold Practice is adapted from the Companion Guide to the Art of Hosting compiled by Steve Ryman and myself in early 2016. My gratitude to Steve, who was the main author of that section. [Where is the Companion Guide published (book, article, website…)?]It isn’t openly available to the public.

[10] In essence, our entire cultural manifestation is a conversation, one which has become ever more global, intense, and polarized through our use of information technologies—hence, the importance and potential of developing our conversational capacity!

[11] See also http://www.margaretwheatley.com/articles/Leadership-in-Age-of-Complexity.pdf

[12] Such methodologies include Circle, Open Space Technology, The World Café, Appreciative Inquiry, etc.

[13] Borrowed from the practice of Open Space Technology.

Freedom to Make Music

Freedom to Make Music

The Pros and Cons Program in Canada mentors people who are incarcerated in a music program that focuses on rehabilitation and restorative justice. The program was founded by Hugh Christopher Brown. He and the incarcerated individuals write, arrange, and record songs entirely within the confines of the prison walls. All music from the program is given freely and anonymously and is downloadable from their website. It is the wish of everyone involved that any monies be directed to three extremely worthy charities listed on their website. Chris Brown spoke to Kosmos about the Pros and Cons Program inception, ethos, recent developments, and plans for the future.

“This civilization has to take responsibility for itself beyond warehousing human beings, and beyond just our acceptance of collective punishment. I’m offering a microphone and something else…” —Hugh Christopher Brown

Kari Auerbach | As founder of Pros and Cons, can you tell me a little bit about the events or the journey that led up to the founding of this program?

Chris Brown | Yes, I started a music studio up on Wolfe Island, which is across the St. Lawrence River from the mainland of Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Kingston is the prison capital of Canada; there are seven prisons there. Everybody in that area is connected to the prison in some way, and one of the deep ways was by the agricultural program, a 200-year-old farming program inside the prisons where they grew food for the food bank and for other institutions. The inmates learned farm skills and animal care, and they developed close relationships with the animals. Then, Stephen Harper’s government decided to destroy that program, which had a 0.1% recidivism rate, meaning if you went through that program, you were less likely to re-offend. So, why destroy a successful program? A lot of my friends who are farmers were getting arrested during the protests. I remember a few of my farmer friends saying, “Chris, you go sing about it.” I thought, “Well, I just need to get inside and do something positive.” I play music, so I just started going inside and playing music.

Kari | What does social justice mean to you? Can you recall the birth of social justice in your music, or is it just an ingrained symbiosis?

Chris | When I was 15 years old, Gil Scott-Heron played in Toronto and I had a great epiphany watching him talk so eloquently about the social temperature of the day. His singing and his social engagement were one and the same. I realized that music has always been about expressing the human condition. Beethoven has a whole symphony set in a prison. What we now know as protest songs are just songs of people’s lives. Secondly, it’s the aspect of ceremony. I grew up Catholic, which has many tiers to it, but certainly music was always ritualized for me as a kid—adding music to the fold of an effort, whether to ease people’s lives or to raise money for a certain cause.

Kari | Tell me about the music sessions you do with people in prisons—how much do you lead or guide? How collaborative are the sessions?

photo: © 2014 Kristen Ritchie

Chris | It’s ever-evolving. The first time I was in there, I just took a guitar… and I was terrified. I’d never been in a prison before, and there were 17 chairs in a semicircle with one in the middle that I was supposed to sit in. I just sat in it and sang a couple of songs. Then I said, “Does anybody know a song?” and they sang to me. A couple of them indicated they were in the chapel choir and they sang a hymn I happened to know, so I went over and sat at the organ and accompanied them. Before you knew it, two hours had passed, because we just started exchanging songs. That was the first day.

The following week, a whole bunch of guys brought notebooks with writing in them. There were songs, poems, and journals. We started talking about writing and right about then, I was asked to do a recording for charity, a symphony or anything of my choosing, so I said, “I want to use inmates,” and I got permission. That was the first recording that we did, their version of my song “Oblivion.” By then I could see everybody was really interested in the process of recording. We ended up making a whole record, and over the course of that, we had to bring the gear in every week, set it up and tear it down. Everyone involved became very acquainted with the technical aspects of engineering. These days, we’ve won the right to build studios in the institutions for the recording equipment, computers, and instruments because that way they’re not dependent on me being there. It’s been working generationally because prison is a very transient place. People are moved from one institution to the other, guards and corrections officers are shifted around continuously, and yet this program has grown by shared knowledge. In the first institution where we started, it’s estimated that there’s been over a thousand people who’ve come through the program. We’re on, I’d say generation four or five of the group, the information gets shared and passed down so that now—as you can hear—the production value is exponentially better. Essentially, what I do now is to come in and listen to what they’re doing and make my comments. Occasionally there’s something that needs to be pulled together, and I also supply the gear. I’m bringing in new instruments every week when I come.

Selah

Oblivion

Kari | Maybe, if inmates would think of themselves as a singer, as a producer, as a recording engineer, then it eclipses what got them there and gives them a place to move on from, which is so important. The engineering and technical aspect is great because that is another set of skills for when they get out.

Chris | Absolutely.

Kari | I want to know how the songs get chosen. You mentioned that they’re writing more and more.

Chris | The way it works is different for each institution actually. In the women’s institution, Grand Valley, John Copping just finished the second record. He works one-on-one with people who bring their songs to him. John Copping is a great artist, songwriter, producer, who started a wonderful music program called Black Ball serving youth in the Toronto area. In Joyce, there are over 50 participants and it’s about them sorting out with each other when they get to use the gear. They’ll go in individually for a couple of hours at a time and work on their own songs and then they’ll ask each other to collaborate. Then there is Collins Bay, where we’ve just started up. One of the graduates is getting folks who were recently incarcerated back in to be able to mentor because that’s a very important step.

Kari | Nice! I wanted to ask you how the program has evolved since it started. Material-wise and methodology too, it seems it has evolved. Can you think of any other ways?

Chris | The music has gone around the globe, and it’s raised the money for a number of causes, you can see the consequence of people’s personal actions inside writing and playing. They can feel this echo from it that’s very positive. A man serving a life sentence said to me the other day that when he was working, “The afternoon went by like a shot,” because you’re pouring yourself into something meaningful. That evolution of folks developing a means of utilizing their life energy towards their own betterment, which then raises a positive societal impact, is a really important formula.

My own evolution has been a continual education in terms of boundaries and the implications of the work. I create a contract in a sense with people I’m working with. I don’t want to know what they’ve done unless they want to tell me. I don’t need to know what they’ve done because that’s already been settled. They’ve been tried and convicted and they’re serving their time. I’m offering a microphone and something else.

Kari | I think a very important and beautiful aspect of the way you work is just meeting people where they are and elevating their skills, working, collaborating and moving on from there.

Chris | When they begin to feel right about that, invariably they want to talk to me about what their crimes are. At that point, we’ve passed that crime being an identity. It’s an aspect of their lives, and I think that’s a more advantageous angle for comprehending it and taking responsibility for it. What’s interesting now is that people are getting out and are choosing whether or not they want to be publicly engaged with the music and the work. If they do, then they’re talking about their crimes, often publicly, which is a huge step. That’s really owning something. All of this has to be done with supreme sensitivity, foremost to victims, and then to these folks who’ve gone through very intense events in their lives. For them to step out of the fray and say, “Yes, I’ve done this and here’s what the impacts are on other people’s lives and my own.” It’s restorative justice. This is always an evolution. It will always be dynamic and case sensitive.

Video

TedX Talk

Kari | What have been some of the transformational aspects of the program for you, for the participants, and for the institutions?

Chris | It’s given me incredible compassion and wonder at some of these corrections officials who I work with who are sainted, though not all of them. I’ve said to corrections officials, “There are former offenders that I wouldn’t want to hang out with, there are corrections officials, I wouldn’t want to hang out with.” And the officials agreed. It’s an incredibly intense position and I admire the dedication. A lot of people you meet working in corrections and in the justice world have themselves experienced victimhood or violence in their family and have decided to make a difference in the world.

Kari | And the prison chaplain…

Chris | Yes, Kate Johnson, who initially got me in there. She was very instrumental in getting this started. A real scion of restorative justice, who has given me great education and insight, and who I sometimes turn to still. I have deep respect for the folks I see working within a system and doing so compassionately, bravely, and sticking their necks out to make differences without being bureaucratic. When you have a population that has zero advocacy, guess what? You can sit on your hands all day, and for those who choose not to, it’s amazing.

Kari | Are the various institutions generally supportive of the Pros and Cons Program?