The Fractured Fractal | Meaning Making in the Psychedelic Multiverse

This expansive essay explores the multiverse as both scientific theory and cultural metaphor, weaving together threads from quantum mechanics, psychedelic neuroscience, religious cosmology, and pop culture. Pick argues that the multiverse—a model of infinite, interconnected realities—mirrors the fragmented yet richly pluralistic nature of modern consciousness in the age of digital hyperconnectivity.

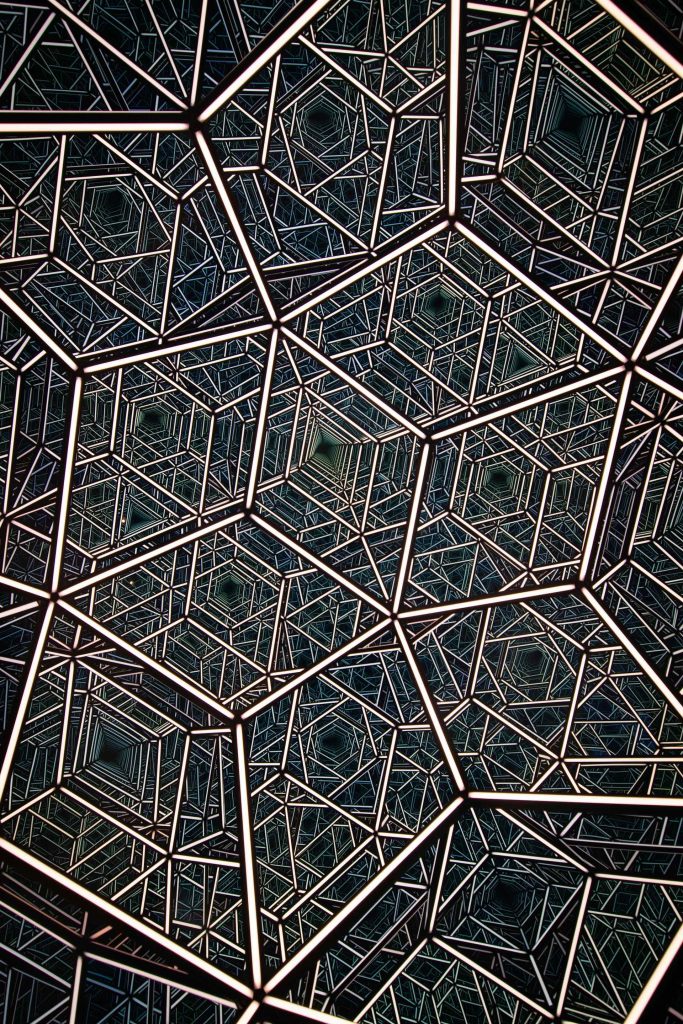

featured image | Daniele Levis Pelusi

Perhaps best known as a mind-bending premise within the big comic book film franchises, the multiverse is central to scores of storylines on- and off-screen, including Meow Wolf’s immersive arts funhouses across the southwest. The multiverse is, well, everywhere. Over the past few decades, the idea has evolved from a heady fictional concept to a valid cosmology supported by a number of scientific theories, including the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. In other words, the conceit that cleverly links many popular narratives may also describe the actual fabric of reality, presenting a dazzling vision of worlds without end that is at once exhilarating and bewildering. Somewhere in between, the multiverse serves as a versatile metaphor for our intensely hyperconnected, digitized lives, and also shares a certain curious resonance with what leading research reveals about the efficacy of visionary and altered states to increase neural plasticity and catalyze adaptive change. Whether or not it describes something real about the nature of the cosmos, the multiverse idea expresses something compelling about the human mind’s ability to expand beyond ordinary confines, forming new connections and exploring creative alternatives to previously intractable problems—all undoubtedly useful capacities for navigating our turbulent, “post-truth” times.

By multiverse I mean the concept of numerous, interconnected universes comprising something approaching the complete set of all possible worlds. This is distinct from the trusted sci-fi and fantasy trope of finite parallel dimensions or alternate realities, such as the Upside Down of Stranger Things, the literalized afterlife world of The Good Place, or the virtual-reality metaverse of Ready Player One. By contrast, the multiverse encompasses a dizzying array of branching universes that together form a vast intersecting web. In some versions, notably theories of the quantum multiverse, a new universe is brought into existence with every diversion in events, or with every quantum measurement, resulting in a fractal propagation of uncountable alternatives made manifest. The multiverse is therefore truly multi, an infinitude of possible realities, a garden of endlessly forking paths.

This Borges reference isn’t incidental—in several short fictions, including “The Library of Babel” and “The Garden of Forking Paths,” the acclaimed author describes infinite universes where “time forks, perpetually, into countless futures,” a vision that not only bears striking resemblance to the multiverse, but predates theoretical formulations of the idea by more than a decade. The history is interesting, because rather than originating as a serious scientific concept later filched for popular storytelling purposes, it’s kind of the other way around. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the word multiverse became associated with the various multiple-universe hypotheses that emerged as a more serious subject of scientific inquiry following discoveries of the accelerating expansion of the visible universe. At any rate, the fictional and scientific notions of the multiverse eventually converged, as multiverses sometimes do, to form the multivalent concept in popular use today as both mind-bending premise and useful metaphor, from the irreverent excesses of Rick & Morty to the heady maximalism of Everything Everywhere All At Once.

***

“Who are you,” the Ancient One inquires as Dr. Strange careens through a cosmic phantasmagoria of cascading dimensions, “in this vast multiverse?” The question comes about thirty minutes into 2016’s Doctor Strange, the first movie to introduce the multiverse idea to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and there’s no mistaking what’s happening—though energetically rather than pharmacologically altered, dude is tripping. That’s the thing about depictions of infinite worlds: from scientific cosmologies to satirical sitcoms, visions of the multiverse are routinely and almost universally described as “psychedelic.” This might just seem like a superficial convention for conjuring up colorful wacky multiplicity, but it actually reveals a much deeper intuition about the multiverse as a metaphor for uniquely mutable human imagination and experience.

Psychedelic here typically refers to depictions of swirling, kaleidoscopic imagery comprising vivid polychromatic and geometric configurations that may initially appear chaotic but gradually deepen to reveal the formation of a larger, complexly-ordered whole encompassing all constituent parts in a harmonious patterning that is often suggestively self-similar at any scale, and therefore endless, as in a fractal, mosaic, or mandala matrix. When animated, such imagery is frequently rendered with a pulsing periodicity, as if it were alive, and shown to reveal or maintain its deep patterning across warping surrealistic transpositions of both time and space. In addition to sharing these qualities, Dr. Strange’s trip is illustrative because his journey across vast regions of telescoping spacetime isn’t simply a cosmic carnival ride, but a radical reorientation to the nature of reality and his own existence, whereby his supposed individuality is subsumed within the interconnected totality of the multiverse. Several times fragmented and reassembled, Strange tumbles through the black hole of his own pupil and appears reflected within the crystalline panes of jeweled galactic apertures as the Ancient One explains that “at the root of existence, mind and matter meet [and] thoughts shape reality,” giving rise to worlds without end.

Psychedelic here typically refers to depictions of swirling, kaleidoscopic imagery comprising vivid polychromatic and geometric configurations that may initially appear chaotic but gradually deepen to reveal the formation of a larger, complexly-ordered whole encompassing all constituent parts in a harmonious patterning that is often suggestively self-similar at any scale, and therefore endless, as in a fractal, mosaic, or mandala matrix. When animated, such imagery is frequently rendered with a pulsing periodicity, as if it were alive, and shown to reveal or maintain its deep patterning across warping surrealistic transpositions of both time and space. In addition to sharing these qualities, Dr. Strange’s trip is illustrative because his journey across vast regions of telescoping spacetime isn’t simply a cosmic carnival ride, but a radical reorientation to the nature of reality and his own existence, whereby his supposed individuality is subsumed within the interconnected totality of the multiverse. Several times fragmented and reassembled, Strange tumbles through the black hole of his own pupil and appears reflected within the crystalline panes of jeweled galactic apertures as the Ancient One explains that “at the root of existence, mind and matter meet [and] thoughts shape reality,” giving rise to worlds without end.

Such descriptions, then, actually are psychedelic, in that they recognizably correspond to both the visual and phenomenological contents of experiential reports with psychedelic substances and related meditative, mystical and non-ordinary states, as well as with the work of renowned psychedelic artists like Alex Grey and Pablo Amaringo. As with Doctor Strange, depictions of psychedelic experiences frequently feature human subjects fluidly interpenetrating, dissolving into, or otherwise merging with higher-ordered visionary realms that appear to overflow with multidimensional significance. While controversial, innovations in generative AI are further amplifying possibilities for hallucinogenic imagery, including the mutating fantasias of several recent psych rock music videos, which immerse the viewer in mind-bending excursions that can perhaps only be described as psychedelic. This isn’t to say that all trips are created equal, nor that they are even primarily visual or visionary. Heavenly or hellish, the subjective perceptual alterations occasioned by psychedelic experiences are astonishingly variable and unpredictable, such that one of the most conspicuous shared features of these depictions is multiplicity itself.

***

However nuanced the quantum multiverse and its related scientific theories may be, the basic idea is actually very, very old. Infinite worlds cosmologies of varying complexity can be found in the multiform dharmic traditions of the Indian subcontinent, including Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as the Atomist and Stoic philosophies of ancient Greece. Much like the assertions of modern physics, these cosmologies all emphasize a distinction between the fundamental components of reality and its perceived appearance. Perhaps the most elaborated pre-modern conception of the multiverse is that of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra, one of the principal works of East Asian Buddhism. A massive multi-volume compilation that is itself fractal in nature, the ‘Flower Ornament Scripture’ describes a vast “infinity of infinities” in which the pores of every enlightening being’s body contain “untold multitudes of buddha-lands filled with buddhas,” who likewise themselves contain a molecular multitude of worlds encompassing “courses of eons, as many eons as atoms in the untold buddha-lands in the succession of worlds.” Extending endlessly in both space and time, throughout the ten directions, it’s buddhas all the way down.

All infinite worlds cosmologies share something of this profound visionary potential, which can stretch our stargazing wonderment to the very limits, shrinking our narrow self-concern and enlarging our sense of possibility until it approaches the infinite. In their kaleidoscopic intricacy, the Avataṃsaka Sūtra’s inspired contemplations ultimately present the multiverse as a concept to carry us beyond conceptual thinking—as a gateway, a wormhole, a finger pointing. For most of us I suspect that the multiverse models of modern physics are similarly evocative, their branes, strings and manifolds taken less as intelligible descriptions of reality, and regarded instead with a kind of secularized awe that inclines toward the sublime. Physicist Brian Greene, who adheres closely to the theoretical science when describing nine types of multiverse in his popular 2011 book The Hidden Reality, affirms that such concepts require us “to abandon comfortable modes of thought and embrace unanticipated realms of reality.” However well we grasp the mathematical or explanatory validity of these theories, they nonetheless convey something appreciable, and essential, about the potentials and limits of human knowledge and perception.

In this way the multiverse idea can also be understood as a metaphor for things we know we can’t fully know, including all the ways that complex systems tend to be deeply interconnected, richly pluralistic, and subject to a variety of causes, conditions and possible outcomes. The presence of infinite possibilities is perhaps the most obvious reason why multiverse narratives are so ubiquitous: they invite our “what if?” speculations along not just one forking path, as is the case with alternate timeline classics like It’s a Wonderful Life and Sliding Doors, but across a tantalizing array of concurrent realities. By finding expression for every potential, multiverse narratives simultaneously indulge and assuage our doubts and fears in the midst of a rapidly-changing, politically-fractious, pandemic-destabilized world. The multiverse is itself an “infinity of infinities,” after all, and therefore provides an apt metaphor for the pervasive tangle of interdependent systems that shape our everyday experience yet elude our full comprehension.

This is perhaps nowhere more immediate than on the internet, where our direct experience is one of endless worlds within worlds, hyperlinked and fractal-dense, the next dimension only a click away. Scrolling even briefly through social media, we encounter a dizzying variety of viewpoints, every post a portal or attention-warping wormhole, a multiversal hall of mirrors. We take this kind of scattershot interdimensional travel for granted, yet research finds that mental health disorders, identity diffusion, and suicidality are all steadily increasing, particularly among young people, in what neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley describes as a growing global cognition crisis resulting at least in part from the fact that “our brains simply have not kept pace with the rapid changes in our environment—specifically the introduction and ubiquity of information technology.” The dopamine casino quality of the internet stimulates a fracturing of cognition that leads to measurable deficits in everything from attention and memory to creative thinking and empathic concern. In other words, these technologies tend to heighten our experience of reality as a disorienting expanse of possibilities that approaches both the infinite and the unknowable—a reality that our nervous systems increasingly struggle to make sense of.

***

In describing our hyperlinked world this way, I’ve also more or less outlined our current sociopolitical landscape. This is no accident—the internet-driven fracturing of cognition has profoundly destabilized both individual and collective meaning making processes. Speaking presciently in 1998, Terence McKenna described it like this:

“Technology, or the historical momentum of things, is creating such a bewildering social milieu that the monkey mind cannot find a simple story, a simple creation myth or redemption myth, to lay over the crazy contradictory patchwork of profane techno-consumerist, post-McLuhanist, electronic, pre-apocalyptic existence. And so into that dimension of anxiety, created by this inability to parse reality, rushes a bewildering variety of squirrelly notions.”

By “squirrely notions” he of course means conspiracies, cult beliefs and crackpot theories of all kinds, which McKenna also calls “epistemological cartoons.” Robert Anton Wilson more broadly refers to all worldviews as the belief systems or “reality tunnels” that enable each of us to organize and make sense of our world. The idea that we inhabit our own self-created universes isn’t new, but neuroscience now provides insight into the ways that our ordinary perception is a kind of “controlled hallucination,” a necessarily simplistic and incomplete map of reality based largely on perceptual predictions. Aldous Huxley famously describes ordinary consciousness as a “reducing valve” by which our brains selectively filter information and sense data to help ensure survival. In mistaking our mental models for reality, our limited worldviews become the totality of our individual and shared worlds, such that “from family to nation, every human group is a society of island universes.”

For all its connective magic, the internet exacerbates the fact that we functionally inhabit island universes. What this often feels like in real time is a continual inundation by myriad alternate realities and conflicting value systems that challenge any stable sense of what’s really real. Amidst this flood of possibilities, dogmatic worldviews tend to become very seductive—especially those centered around solidified personal identity—until we find ourselves beset at every turn by embattled positions and entrenched views. This phenomenon isn’t restricted to any one side of the political spectrum, and the surreal overlap in shared reasoning styles has become more apparent than ever, as Julian Walker insightfully outlines in analyzing the many strange congruities between the alt-right and New Age. Amplified by technology, this constant information overload has radically undermined cultural meaning making processes, replacing shared maps of reality with a paradoxical climate of acute paranoia, tyrannical certitude and outright magical thinking. Squirrely notions abound.

The result of all this destabilization is our current cultural pressure cooker, in which political division is no longer even superficially limited to issues of governance or red/blue affiliation, but is characterized instead by what Peter Limberg and Conor Barnes call memetic tribes, a type of ideological affinity group that “directly or indirectly seeks to impose its distinct map of reality—along with its moral imperatives—on others.” The social fabric is no longer made up of parallel island universes, but is instead largely defined by warring worlds vying to control the narrative and decide what our core social facts will be. These circumstances aren’t merely a reaction to increasing complexity, but have often been deliberately engineered, utilizing technologies and political tactics that take advantage of multiversal multiplicity to further destabilize reality for monetary or political gain.

The upside here (there is an upside, right?) is that our core social facts are no longer solely determined by a hegemonic consensus reality structured around capitalism, racism, patriarchy, colonialism, militarism and the rest. Those particular reality tunnels are still with us, and they’re still vying for ascendency as aggressively as ever, but they no longer hold the same monolithic sway. Engaged in an information exchange of unprecedented richness and diversity, a growing plurality of voices is offering innovative alternatives for social organization and cohesion. The abundance of multiversal possibility is profoundly double-edged, however, at once liberating (“It could be different”) and overwhelming (“It could be anything”). What we believe matters, and at a time when numerous planetary crises dispel any illusion of our separateness and challenge us with novel opportunities for unity and cooperation, we’re confronted instead with a vehement and divisive backlash that threatens to undermine democratic process itself.

This is often the immediate reaction to difficult realities, when destabilization leads to entrenchment and proliferating choice leads to inertia rather than action. Life in the multiverse can be a bit of a shitshow, in other words, as is expertly dramatized by many popular narratives. The directors of Everything Everywhere All At Once, for instance, overtly embrace the multiverse in search of storytelling “that can hold it all together” amidst a global meaning-making crisis in which cultural narratives no longer unify us. Making sense of reality in a “post-truth” world can be a formidable task, after all. So what can tales from the psychedelic multiverse teach us about navigating the garden of forking paths?

***

As clinical research over the past decade has helped bring psychedelics into the mainstream, demonstrating tremendous potential for their use as therapeutic medicines, it’s notable that a certain straightforward presentation of positive benefits is becoming something of a litany, as in this typical example from Newsweek: “people who take these substances have reported powerful mystical experiences that are often characterized by a sense of unity or oneness, a profoundly positive mood, a sense of ineffability, and transcendence of time and space.” While unity can be a significant feature of psychedelic experience, mainstream media descriptions commonly favor oneness and bliss over variability and multiplicity. Doing so can omit compelling insights about the brain and consciousness that have emerged from recent psychedelic research.

Robin Carhart-Harris’ entropic brain theory, for instance, posits that the default mode network, which normally regulates the brain’s ordered functioning and maintains an active sense of self, is temporarily disinhibited by psychedelic substances. The resulting increase in brain entropy and neural plasticity allows for higher information exchange, creative linkage and depth of experience, such that “the brain operates with greater flexibility and interconnectedness.” Carhart-Harris and renowned neuroscientist Karl Friston have expanded the entropic theory into what they call the REBUS/anarchic brain model, which proposes that in so doing, psychedelics can decrease hierarchical brain functioning and significantly relax the pathologic beliefs and assumptions that underlie mental suffering.

In Carhart-Harris’ work, entropy is synonymous with uncertainty, which our brains normally suppress when employing the heavily filtered, predictive processing that creates and maintains our island universes. By increasing the entropy of spontaneous brain activity, psychedelics can engender a more expansive conscious experience, relaxing the constraining influence of the entrenched, habitual views that shape many of the brain’s predictions. That this is possible does not mean that it’s inevitable, however, nor that it’s always pleasant—like early pioneers in the field, contemporary researchers continue to affirm the importance of set and setting, proper integration, and the value of ceremonial and therapeutic contexts for psychedelic use. “Psychedelic” is a neologism that means “mind-manifesting,” after all, and what’s being manifested appears to be the brain/mind’s potential to “spontaneously transition between states with greater freedom—and in a less predictable way,” such that access to the mind’s contents and capacities is radically enhanced. We might even say that the mind becomes more multiversal, more capable of engaging our dynamic and disorienting world with assurance rather than apprehension.

This may seem counterintuitive, given that multiversal complexity has just been suggested as a potential culprit in our ongoing meaning making crisis. But while perhaps more prevalent than ever before, complexity has always been with us. The issue isn’t necessarily the deluge of information itself, but our limited ability to make sense of an apparently chaotic expanse of seemingly contradictory or unresolvable potentialities, especially when exacerbated by the internet-intensified vortex that now shapes reality.

Our brains attempt to solve this problem by adopting simplistic stories or reality tunnels, in large part because the default mode network prioritizes the mental construct of a separate, individual self, which then serves as the central reference point for all conscious experience. Filtered this way, our picture of reality is, well, essentially a selfie, hyperfocused on organizing the limited set of past experiences, present beliefs and future expectations that defines our self-identity. This ordering principle has powerful adaptive advantages, but exerts excessive control on the brain, constraining perception and cognition. By catalyzing high-entropy mental states, however, psychedelics can heighten the brain/mind’s integrative and connective capacities to more readily accommodate multiplicity and uncertainty. As Michael Pollan explains, “the increase in entropy allows a thousand mental states to bloom, many of them bizarre and senseless, but some number of them revelatory, imaginative, and, at least potentially, transformative.”

In practical terms we might imagine something like a recent encounter I had walking down Denver’s East Colfax Avenue late one night, where I passed a barefoot young man splayed in a vacant doorway, underdressed for the season, the orange lighter and charred glass stem on the cracked sidewalk before him his only evident possessions, his nowhere stare not really seeing me, his mumbled request for change perfunctory, almost an afterthought. It’s one among many similar encounters in the space of a quarter hour, and on an ordinary night I might simply filter him out as “homeless” or “addict” or “mentally ill” without ever really seeing him, either. Just like that, we other—whether willfully or habitually, we all too easily ignore, dismiss, overlook, exclude. With a little more openness, however, I might instead recognize the evident suffering he’s carrying and the humanity we share, might even see that he could very well be my student or my son, could even be, down some darker timeline, me. And just like that, the moment flowers in a multiverse of possible worlds—the one where I befriend him; the one where I condemn him; the one where I report him; the one where I join him; the one where I suppress my feelings and do nothing; the one where the something I do is write about it. But more open still, and my habit of self-concern might further relax, dissolving my armor of individuation and enabling me to more deeply feel, and even to act upon, the kernel of care that has briefly burst open within me. Recognizing that we inhabit radically different worlds, my frames of reference fall away, welcoming a moment more immediate, crystalline, and maybe even shared. What then, among our multiverse of possibilities? Tomorrow never knows.

The prospect that greater cognitive flexibility can support deeper feelings of empathy and interconnectedness certainly resonates with recent research and reports of altered and mystical states, where experiences of transcendence, interfusion and universal love are not only prevalent, but often appear to occasion enduring functional changes. As entropic brain theory indicates, however, cognitive flexibility of this kind arises during states of increased ambiguity and generative disorder, which can be acutely distressing. Friston and Carhart-Harris acknowledge these risks by noting that “poorly integrated experiences could leave individuals awash in uncertainty and eager for solace in tenuous, or, worse, delusional beliefs that serve to stop-gap uncertainty.” Thing is, as we’ve already established, that’s precisely the state in which we find our current social order—as a simultaneously hyperconnected and haphazardly fragmented pressure cooker on overdrive.

It might seem contradictory to suggest that mental health can be improved by introducing still more cognitive disorder, even if only temporarily and in a regulated therapeutic setting. But again, as recent research indicates, the problem isn’t overload or uncertainty itself, but our brains’ limited tolerance of indeterminacy. The issue, in other words, isn’t too little order, but too much. All fundamentalisms and extremisms adhere to the brittle certainties of dualistic and dogmatic thinking, adopting highly controlled limits to impose an atrophied but internally coherent picture of reality. This includes cultic, conspiratorial and purity-centric beliefs across the spectrum—worldviews that have proliferated amidst the overwhelming irruption of multiplicity over the past few decades. It’s the planetary equivalent of a bad trip that has so far gone unintegrated, and resembles a phase of the psychedelic experience that Andrew Gallimore likens to channel surfing, when the brain begins to “move in a disorderly fashion through an expanded number of different patterns of neural activity … [as if] fumbling with the dial attempting to retune itself.” By loosening the default mode network’s habitual patterns, psychedelics not only subvert the brain’s tendency towards egocentric and ideological rigidity, but free the mind to discover new forms of meaning. And without both individual and collective expansions of meaning-making, we risk remaining stuck trying to solve problems with the same thinking that created them, or worse, remaining adrift in a relativistic limbo of perpetual distraction and inaction, as many multiverse narratives are inclined to warn us against.

***

In the 2016 film, after Dr. Strange is awakened to the vastness of the multiverse, he quickly masters the associated mystic arts and begins manipulating both space and time with the aid of energetic mandalas and other geometric sigils. It’s a superhero movie, after all, but one that playfully engages its many psychedelic tropes. For the 2022 sequel, In the Multiverse of Madness, Strange is able to freely travel between dimensions with the help of young hero America Chavez. Aside from one scene in which the two briefly traverse more than a dozen bizarre universes, however, the events of film mainly take place in a handful of recognizable alternate realities that conform to a conventional earth, heaven and hell schema. The film does explore some basic “what if?” themes, but the allure of infinite possibilities is unambiguously presented as treacherous. Instead, the multiverse idea primarily supplies a conceit for the combination of Marvel properties, serving up a facsimile of multiversal complexity that offers little meaning beyond its own increasingly entangled, self-referential spectacle—a problem openly criticized in later films.

Embracing both spectacle and complexity, the long-running animated series Rick and Morty gleefully exploits the multiverse idea to explore the storytelling possibilities and philosophical implications of infinite worlds. The show follows sociopathic mad scientist Rick and his earnest, anxious grandson Morty, who together form “a dialectic of damaged maleness,” as they cast about on interdimensional misadventures involving knotty sci-fi premises such as a love affair with a planet-wide assimilating hive-mind, an extraterrestrial counseling institute that materializes couples’ perceptions of one another, and a trans-dimensional city-state inhabited entirely by Ricks and Mortys from countless alternate realities. The show’s commitment to its story lines yields entertaining and mind-bending results, but for all the anarchic, parodic, and often cringey fun viewers might find, the characters (especially male) are generally not ok. Rick self-medicates while fiercely defending a narcissistic, nihilistic worldview, Morty bungles his own naive attempts at moral integrity with frequently catastrophic results, and his petulant father Jerry oscillates between withering self-doubt and willful denial. Prolonged exposure to multiversal relativism and the apparent absurdity of existence not only deteriorates everyone’s mental health, but often leads to further entrenchment within existing self-centered beliefs and other coping mechanisms. Rick and Morty cares deeply about investigating the possibility that nothing matters, and makes great effort to establish plausible deniability about this paradox, which lies at the show’s (sarcastically beating, dark matter-powered) heart. But for all its enthusiastic flash and cynical recoil, the show typically resolves with the family achieving domestic ceasefire and returning to the couch to watch TV together—less an integration of multiplicity than a retreat into familiarity.

As metaphor for our contemporary cultural cacophony, these multiverses pull few punches. Both the MCU and the world of Rick and Morty affirm the deleterious effects of information overload, existential uncertainty and a superabundance of possibility, so it’s no surprise that mental health and the pervasive cognition crisis are key themes. The “madness” of the Doctor Strange sequel refers to Wanda’s and Strange’s slipping sanity amidst the overwhelm of alternate realities, where they witness versions of themselves succumbing to brutality and destruction. For Marvel’s mystical superheroes, as for mad scientist Rick, these narratives emphasize the chaotic and reality-destabilizing consequences of such power, rather than simply its corrupting influence. These are essentially cautionary tales, though our protagonists manage to escape a more unpleasant fate by acquiescing to the strictures and conventions of their native timelines, presumably wiser in the knowledge that the nature of reality exceeds their understanding or control. That’s true enough, and an important starting point for sense-making, but beyond warning us away from similar folly, both story worlds fail to provide helpful strategies for skillfully navigating the continued encroachment of multiversal complexity into our everyday lives.

Other multiverse narratives take a different approach, however, mapping the same dangers but offering decidedly different responses. The multiverse idea is an essential connective element in the concept and design of Meow Wolf’s hugely popular immersive arts projects, including permanent installations in Santa Fe, Las Vegas and Denver, where visitors can choose to wander freely or attempt to follow each location’s unique puzzle-like narrative. Convergence Station in Denver, for instance, centers around the story of four worlds that have become entangled with ours in a mysterious cosmic event. Beset by psychic aftershocks, citizens’ memories are so scrambled that the exchange of “mems” forms the basis of the convergence’s economy. This sci-fi premise—perfect for a multi-level psychedelic labyrinth—supports an interactive narrative that unfolds like an elaborate scavenger hunt. Here, too, fragmentation and complexity are part of the story, but visitors are invited to creatively engage through spontaneous, childlike play, recalling lost memories or making new ones, and, like the convergence’s citizenry, actively piecing together or inventing one’s own meanings as part of the experience. Once inside, eyes alight, confusion gives way to a heightened state in which seemingly disparate worlds begin to cohere into something greater than the sum of their parts. Rather than shrink from ambiguity and overload, Meow Wolf prescribes full-scale exploratory immersion.

And then there’s Everything Everywhere All At Once, the acclaimed 2022 film whose title perfectly describes both the multiverse, by any conception, and the world for which the multiverse has become metaphor—the world we live in, where multiplicity is unavoidable and unfathomable in about equal measure. This multi-genre gonzo epic has been labeled sci-fi action comedy, though the London Review of Books perhaps more accurately describes the film as a “philosophical soap opera.” It’s a uniquely wild ride, by turns exhaustive and exhausting, where the multiverse also importantly serves, as Anne Anlin Cheng highlights, as metaphor for the immigrant Asian American experience, and by extension for the “the dislocations and personality splits” of many identities. Like Rick and Morty, the film takes the possibility that nothing matters as one of its central concerns, at once a psychological, generational and existential challenge depicted most vividly in the experience of teenage daughter Joy, but present in every character’s sense of failure and missed opportunity. There are fight scenes and goofball antics and poignant interludes, all tethered together with a head-spinning music-video momentum that blurs cosmic as the film progresses, coalescing in a googly-eyed psychedelia that contains multitudes.

As manifest in an alternate persona, Joy’s fractured mind simultaneously experiences all universes as a library of infinite possibilities, which she draws from at will while waging a destructive campaign to confirm that existence is meaningless, and thereby essentially becoming the interdimensional equivalent of a haute couture internet troll. By attempting to help her daughter, Joy’s mother Evelyn experiences a similar rupture, and is eventually tempted by the same nihilistic allure. Rather than succumb to or retreat from engulfing multiplicity, however, Evelyn instead heeds the wisdom of her soft-spoken husband Waymond, who urges her to choose to see the good side of things, and to please be kind, despite the confusion and uncertainty we all experience.

This advice, so easily mistaken for wispy sentimental cliché, takes on a refreshing concreteness amidst the absurdist maximalism of the film. Rather than dismissively filter out Waymond’s loving plea, Evelyn experiences it anew, rich with resonant meaning, and is inspired to use the full expanse of multiversal possibility as a source of transforming power, creatively remedying the suffering of her adversaries by pacifying them with sudden happiness. It is fanciful and ridiculous and sublime—a kind of psychedelic kung fu that transmutes aggression into delight through spontaneous acts of creative love. Not surprisingly, exercising this newfound skill is a little more workaday back in our familiar timeline, as we see when Evelyn and Joy reconcile. “So awkward,” Joy groans after they embrace, but it’s clear that their relationship has deepened, not only in Evelyn’s acceptance of Joy’s sexuality, but in their surrender to a love that is freely chosen, despite everything.

***

In this way, the prospect that nothing matters is transformed from a nihilistic rejection of meaning into an affirmation of possibility, not the dead end of a fruitless search, but a liberatory beginning from which to create purpose and value. Rather than retreat within the brittle certainties of prescriptive beliefs, this multiversal awareness accepts uncertainty as the necessary starting point for an expansive curiosity that welcomes the world in, eager to learn as much as possible while appreciating that the full grandeur and mystery of the cosmos may forever exceed our understanding.

Well sure, easier said than done. Because again and again, our brains default to ordered patterns that maintain an active sense of self by constraining perception and cognition within fixed modes of filtered, predictive processing. Flashes of novelty or insight may disrupt these patterns, but familiar habits of thinking and behavior soon reassert control as the autocratic rulers of our island universes. This may especially be true of many psychopathologies and trauma responses, which Friston and Carhart-Harris propose are developed through “the entrenchment of pathologic thoughts and behaviors, plus aberrant beliefs held at a high level.” Such beliefs often exert undue influence on the self-identity or ego structure, and can be very difficult to access and alter. Research confirms that a variety of therapies, that a variety of therapies, meditation practices and other modalities can relax these default patterns and facilitate enduring changes over time. And occasionally the measured pace of these methods may benefit from the support of powerful catalysts that can, given the right conditions, reliably occasion states of heightened plasticity conducive to embodied, revelatory insight.

This returns us to psychedelics, which have the ability to temporarily destabilize and reconstitute consciousness in ways that can measurably retain healthier and more harmonious brain functioning, as well as expanded connectivity, openness and alignment. The classic psychedelics are not only proving to be remarkably effective in treating PTSD, addiction, and other disorders, but demonstrate tremendous potential in helping people of all kinds deepen our inherent human capacities for self-awareness and self-authorship. By relaxing rigidly held beliefs and assumptions, psychedelics can free the mind to synthesize and integrate new forms of meaning as part of a holistic healing process. This is partly why many indigenous traditions regard psychedelics as medicine: because they view the healing of physical and mental symptoms to be inseparable from addressing underlying psychological and spiritual constrictions, both personal and collective.

Whether with a rush or a gentle nudge, these medicines offer admittance into states of being beyond ordinary confines, where the separateness of self and other gives way to an interconnected totality that is continuous with the living planet, the cosmos, the infinite. And then, when the world’s endless forms return, they do so not as isolated and conflicting rivals, but as part and parcel of a witnessed and welcoming whole, a coherent manifold chaos whose order and inexplicable rhythm is ever-evolving.

As conjecture and metaphor, the multiverse represents the idea that myriad complex, even apparently contradictory systems—whether thought worlds, or actual worlds, or something in between—can not only functionally co-exist, but can interconnect in diverse, multifaceted relationships whose dynamic cohesion and recursive density may only be evident at certain scales. A multiversal awareness therefore includes a high tolerance for ambiguity and a contextual appreciation for the simultaneous presence of both boundless potentials and bounded perception, of possibilities and limits. Because cognitive flexibility of this kind is developed experientially, it’s doubtful that “non-hallucinogenic” drug derivatives will offer the enduring, transformative impact of the classic psychedelics, as some researchers hope. The trip is a feature, in other words, not a bug. And why should we expect otherwise? Change is hard because our brains are adept at encoding protective patterns, plus preserving the hardwired propensities and reward cycles that many technologies now deliberately and addictively exploit. For good or ill, the hyper-connected multiverse of our ever-accelerating, data-driven world is revealing reality itself to be vertiginously multiple and endlessly alternate, challenging our deepest adaptive abilities. As versatile catalysts, psychedelics may offer uniquely effective pathways for expanding and restabilizing both individual and collective meaning-making capacities.

This doesn’t mean that we should start dosing the drinking water or reviving the acid tests, however—research supports a measured enthusiasm informed by the importance of context and integration, especially as provided by ceremonial and therapeutic approaches. Additionally, Brian Pace and Neşe Devenot make the case that “conservative, hierarchy-based ideologies are able to assimilate psychedelic experiences of interconnection,” suggesting that temporarily increased cognitive flexibility does not inevitably lead to specific progressive values or beliefs. That’s the multiverse for you. Psychedelics aren’t a universal panacea—as ever, we have before us the hard work of healing, all down the line of our ancestors and on up into the branching world tree of our as-yet unmapped possibilities, which bloom forth in interlocking geometries of infinite depth and resonance, only to recede again as faintly whispered invitations for our hearts to follow as we seek pathways toward greater freedom, pathways beyond fear.