Redefining philanthropy’s purpose and role by centering social movements

featured image | “Otra Onda Viene” (Another Wave Comes) by Alixa Garcia

The question of how philanthropy relates to social movements gets to the crux of the very purpose and existence of philanthropy. This article makes the case for philanthropy to lean into discomfort, grapple with hard truths, and follow the lead of those who are most impacted by the root causes of oppression, who are creating powerful solutions as a path towards post capitalist worlds.

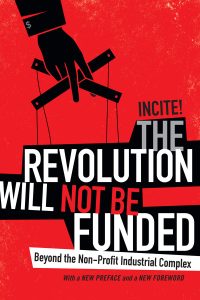

Why discomfort and hard truths? Put simply, the money we are working with does not come out of nowhere; it is both an input and output of the very systems we are ostensibly working against. As abolitionist scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore clearly articulates, “philanthropy is the private allocation of stolen social wages…” And as the seminal book on philanthropy, The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, explains, the philanthropic wealth is actually thrice stolen – profits stolen from low-wage and enslaved labor, sheltered from taxes, and made on stolen land.

Why discomfort and hard truths? Put simply, the money we are working with does not come out of nowhere; it is both an input and output of the very systems we are ostensibly working against. As abolitionist scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore clearly articulates, “philanthropy is the private allocation of stolen social wages…” And as the seminal book on philanthropy, The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, explains, the philanthropic wealth is actually thrice stolen – profits stolen from low-wage and enslaved labor, sheltered from taxes, and made on stolen land.

When funders operate under the illusion that the funds we hold are “ours” to redistribute, we situate ourselves in a position of power vis-à-vis the recipients of those funds. We set the priorities; determine desired outcomes; create our own theories of change; and see it as our job to curate nonprofits to carry out our foundation’s strategy in exchange for grants.

But when we take as our starting point that we are holding stolen wealth, with a moral imperative to return it to the people, our work looks very different. The process of returning the wealth can be reparative and healing, and can turn complicity into solidarity. When complicity stops, solidarity begins. In that process of practicing solidarity, fortunately, there are highly organized and effective social movements whom we can turn to, composed of and led by frontline communities, who are paving the way toward transformative change.

Philanthropy must be a site of contestation

More funders are waking up to the power of social movements. In the US, this awareness has come hard fought through the radical and impactful racial justice/Black Lives Matter/prison abolition movements, LandBack and other Indigenous sovereignty movements, feminist, migrant justice, ecological/climate justice movements, and Palestine solidarity movements, among others. Some of these movements are articulated within broader global movement networks that have been organizing for decades against colonial interventions, free trade agreements, and other tools of the neoliberal global regime, with its concurrent brutality on both people and Mother Earth.

While social movements have received a degree of recognition and acceptance by philanthropy, too many funders only engage with them out of a diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) obligations as opposed to a deeper understanding of how necessary social movements are and how they work. Furthermore, some are funding social movements at the same time that they are providing substantially more funding to projects undermining these very efforts, projects predicated on sustaining capitalism by making it appear kinder, gentler, greener, and/or more equitable.

We argue that simply including social movements in portfolios of the existing status quo of philanthropy is not enough. Philanthropy is a sector that has caused enormous frustration and uncertainty to movements at best, and at worst, has exerted control over, extracted from, and taken credit from progressive groups while absorbing them into the reformist non-profit industrial complex. We must break these cycles, or they will continue to do real and lasting harm.

For progressive funders, philanthropy must be a site of contestation. And not just a source of funding. Movements develop sophisticated campaigning and organizing strategies to win policies and shift power. We need to do the same to shift resources, narratives and practices within philanthropy. This means we need to invest in political education and in organizing donors.

And then we can imagine – What if philanthropy became a movement support sector that was entirely in service of and accountable to movements? What if philanthropy supported the financial autonomy of social movements and not a set of prescriptive outcomes divorced from political and historical contexts? What if we provided reliable and politically aligned funding and solidarity for the long-term? What if we mobilized enough resources to support the global scale, diversity and depth of the movement building and infrastructure needed to address the magnitude and urgency of today’s multiple crises? What if we funded social movements like we wanted them to win?*

Why support social movements as a philanthropic strategy?

The following are some of the reasons why we feel philanthropy should get behind social movements if we truly want to have maximum impact for social and ecological transformation:

Social movements have root cause analysis, making their solutions and visions systemically transformative.

Social movements practice powerful root cause analysis that highlights the historical underpinnings of current crises; traces power to its sources; and identifies how systems of oppression intersect and feed into each other. Their analysis details how the crises at present are the consequence of systems built on exploitation of both people and the natural world. Just as they are clear on how we got ourselves into current crises, they are similarly clear on how we can get out of them, offering visionary yet practical solutions focused on system-wide change.

Some of the multiplicities of systemic frameworks, visions or cosmovisions we are inspired by include buen vivir, feminist economies, food/energy/territorial sovereignty, rematriation, eco-feminism, grassroots feminisms, just transition and more.

Social movements are where resistance and construction co-exist.

Social movements work to fight the bad (what is causing harm) and build the new (what is culturally and materially necessary to sustain life itself). The report Protesta y Propuesta (Protest and Proposal) explains how movements in Puerto Rico are both visionary and oppositional as they resist oppression while constructing alternatives. The construction is driven by diverse but aligned visions of food, energy, and territorial sovereignty, buen vivir, solidarity economies, and feminist economies, among others.

All over the world, social movements are creating worker cooperatives, communal land titles, healing centers, restorative justice projects, agro-ecology farms & schools, community kitchens, mutual aid projects and more, as alternatives under construction, often resulting from hard fought victories from steadfast resistance.

These projects serve a dual purpose as a bridge to the next system, in that they demonstrate that economic, ecological alternatives are possible, and create spaces for people to have lived experiences of agency, democracy and freedom prefiguring a taste of post capitalist formations where life and relationships are free from the profit motive and the commodification of everything.

Social movements show us we cannot separate people from nature.

From agroecology to land rematriation processes, social movements’ visions go beyond economic transformation to holistic restoration of the relationship between people and Mother Earth. For Indigenous movements, this relationship is even more integral, as conveyed by Berta Cáceres of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH): “In our worldview, we are beings who come from the Earth, from the water, and from corn. The Lenca people are ancestral guardians of the rivers…COPINH validates this commitment to continue protecting our waters, the rivers, our shared resources, and nature in general, as well as our rights as a people.”

Through social movements, people facing systemic oppression organize themselves to build collective power to liberate everyone.

Part of what makes social movements so powerful and effective is the fact that they are built from the base by those who are most impacted by those facing intersecting systems of oppression. Recognizing the transformative potential and agency of each person, they unite those who might otherwise feel powerless and dispensable into a force for change capable of transforming the world. As Paulo Freire states, “It is only the oppressed who, by freeing themselves, can free their oppressors.”

Social movements save lives.

When crisis strikes, social movements are often the first to mobilize their infrastructure and people to save lives through emergency relief grounded in mutual aid and solidarity. As detailed in the report Response and Resistance: Social Movements, Covid & Converging Crises, in the face of government abandonment and inefficacy, social movements were able to hit the ground running in their pandemic response, saving countless lives, because they already knew the lay of the land in their respective communities and had extensive networks built through trust over years of community organizing.

Social movements offer moral and political clarity.

As of this writing, Israel has killed more than 32,000 Palestinians in an ongoing genocide. While politicians are mired in geopolitical and economic calculations, and philanthropy is debating the terminology of genocide and Zionism as people are massacred and starved daily, Palestinian social movements are telling the truth of what is happening, calling on the world to take action based on justice and moral clarity. The global public opinion is changing because the solidarity movement led by social movements around the world is shifting the tide from the horrific genocide and its justifications toward freedom for Palestinians and just peace in the region.

Social movements embody visions driven by love and life.

The work of social movements is ultimately a labor of love in affirmation of life, as captured in this video by Brazil’s Landless Workers Movement (MST) on its pandemic response set to the song “Yo Vengo a Ofrecer Mi Corazón” (“I Come to Offer My Heart”). Another powerful example is the Berta Cáceres International Feminist Organizing School (IFOS), that brought together feminist movement leaders from more than 40 countries. IFOS participants developed a collective analysis and vision for feminist economies centering the sustainability of life in response to the project of death wrought by war, genocide, militarization, and extreme exploitation and extraction.

Toward Praxis of Solidarity Philanthropy and Liberation

To close, there are many compelling reasons for philanthropy to center social movements in its work, and here we wish to highlight one more: the transformative potential for those of us working within philanthropy. Committing to be in right relationship with social movements means moving beyond limiting (and arguably misleading) titles of “donors” and “funders” to step into true ally-ship with movements, with all that it entails. We can engage with our whole self – our conscience, our political consciousness, and our actions – in praxis. Solidarity is constant, on-going praxis.

Our movement partners often tell us we are their political ally and funding is one part of solidarity, along with other forms of solidarity and accompaniment. As we are experiencing through our crisis response to the genocide in Palestine, our ability to witness, to speak out, to join protests and take other actions calling for a ceasefire and stop to US arms shipments to Israel and other demands, have been just as important as donating funds. Being in solidarity required us to accompany the movements with our whole selves.

We end with the familiar words of Lilla Watson and other Aboriginal people, “If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

***

The authors wish to thank the Staff and Board of Grassroots International for contributing to this article which is a reflection of our collective insights and experiences. Grassroots International is a global movement support and grantmaking organization that accompanies social movements for systems change.

Terrific article, Chung-Wha and Sara! You make such an important point at the beginning: “the philanthropic wealth is actually thrice stolen – profits stolen from low-wage and enslaved labor, sheltered from taxes, and made on stolen land,” and your list of characteristics of social movements is insightful (and inspiring!). Thank you.