First There Must Be an End

Featured image | David McMillan: Growth and Decay

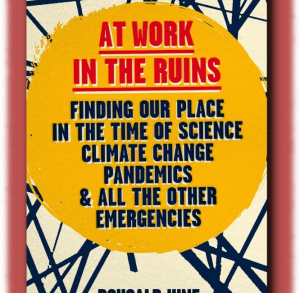

The following is an excerpt from Dougald Hine‘s new book At Work in the Ruins (Chelsea Green Publishing February 2023) and is printed with permission from the publisher.

Here are two claims I have found that I can steer by.

Here are two claims I have found that I can steer by.

The first comes from the closing lines of a manifesto that a friend and I wrote, nearly fifteen years ago now: The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world, full stop. Unless we can inhabit that distinction, we will end up defending the world as we have known it at all costs, no matter how monstrous those costs turn out to be. Think of the desperate schemes for geoengineering already being drawn up. Think of the walls being built to defend against those already displaced by changing patterns of sea, rain and heat. How we name what is at stake will determine what we are prepared to do.

The second claim came out of the conversation started by that manifesto: The end of the world as we know it is also the end of a way of knowing the world. When a world ends, its systems and stories come apart, even the largest of them: the stories that promised to explain everything, the systems that organised all that could be said to be real. It’s not that those stories had no truth in them; it’s not that there was no reality in the description of the world those systems offered. It’s that they couldn’t hold. The things they valued betrayed them; the things they left out came back to haunt them.

One name for the world as we have known it is modernity; one name for its way of knowing the world is science. So [my book, in part, is] about navigating the end-times of modernity and what happens to science as its world ends.

***

Here’s one more story from the Covid spring. I remember this post like a message in a bottle, thrown into the storm of social media, back in those first weeks. It was lost in the tide of memes and takes, I don’t know how to find it, but the author was a climate scientist. Already the lines were being drawn and there was a take going round that went like this: ‘Has anyone noticed how the people refusing to follow the Covid science are the same ones who refuse to accept the climate science?’ Hang on a minute, this climate scientist said, it’s taken decades of careful work to be able to say with confidence the things that my colleagues and I can tell you about climate change. Please don’t treat that as equivalent to what it’s possible to say about a virus that was only identified a few weeks ago.

The iterative nature of the work of science means that the state of knowledge will vary from field to field. With a new object of study, it’s hardly surprising if what the researchers think they know turns out to change from week to week, in contrast to the well-grounded consensus that can emerge in a mature field. But the political rhetoric of ‘following the science’ disregards these differences, casting a singular authority over whatever is said in the name of science, so that the first provisional findings about a new disease are presented as though they were established certainties.

Science in general – and climate science in particular – is not well served by this ideological conflation. Yet, this is a problem that runs deep because the multitude of methods and practices that make up the work of science have been entangled for centuries with a singular story that grants this way of approaching the world a monopoly on telling us what is real. It places a burden on the scientists’ shoulders that was always going to prove unsustainable, but we are living through an intensification of this logic that will push it to breaking point.

One of the questions running through this book is how far, and in what shape, the work of science might survive the end of the world in which the story of science took shape. I might as well say now that I don’t have an answer; it’s not the kind of question that can be answered with a book, but what a book can do is make an invitation to the kinds of conversations and encounters that might be called for, that might help us find some paths into the unknown world that lies ahead.

***

‘In these times, all we can do is be a sign,’ a father tells his daughter in Ben Okri’s novel The Freedom Artist. ‘We have to help to bring about the end of the world.’ We must do this, he goes on, so that a new beginning can come. ‘But first there must be an end.’1

It matters which world we think is ending, and it matters what we tell each other is worth doing in such a time. Among the people we’ll meet in the story I tell, are those who have dedicated their lives to the study of climate science, those taking desperate measures as activists to break the trance they see around them and those inside existing institutions who have been shaken to the core by what we know and what we have good grounds to fear about the trouble in which we find ourselves. There can be a danger in allowing that trouble to be defined solely in terms of climate change, but I’m convinced of the importance of each of these roles in these times. I’m also convinced that other roles need playing and other kinds of action are called for. There’s a lot to be unfolded along the way, but let’s have some leads to get us started, taken from a few of those who have helped to shape my thinking.

First there must be an end – but many kinds of end are possible. My friend Vanessa Machado de Oliveira wrote a book called Hospicing Modernity.2 The title invites us to a kind of work in which the focus is not on saving modernity, or bringing it down, or rushing to build what comes afterwards, but doing what we can to give it a good ending. To let it hand on its gifts and teach the lessons that may only become apparent as the end approaches.

‘It may seem like this book is trying to kill or destroy modernity by announcing its death,’ she writes, but this is ‘something no book can do.’ It’s a warning that applies here, too.

No one I’ve met has more to offer by way of tools for the work of hospicing, but the way Vanessa tells it, this must be accompanied by a work of midwifery: assisting with the birth of something new, unfamiliar and possibly (but not necessarily) wiser, and avoiding suffocating this new world with our projections.

The philosopher Federico Campagna speaks about living at the end of a world.3 In such a time, he suggests, the work is no longer to concern ourselves with making sense according to the logic of the world that is ending, but to leave good ruins, clues and starting points for those who come after, that they may use in building a world that is – as Vanessa would say – ‘presently unimaginable’.

They may be here already, the builders of that world. Some of them may have been here all along, inhabiting the ruins made by the world of the powerful. The anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing wrote a book called The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins.4 That could be a role to take in times like these, to go looking for possibilities of life among the ruins around and ahead of us.

I don’t write to announce the end of the world or to change the minds of those who are convinced that the world as we have known it can be saved or made sustainable. I write for anyone who has found themselves, as I have, needing to make sense of what is ending, how we can talk about it and what tasks are worth taking on in whatever time it turns out that we have.

Something is coming over the horizon: a humbling from which none of us will be spared, that will not be managed or controlled, but will leave us changed.

Before it is over, I suspect, we will need to learn again what it means to take seriously things that are larger or smaller than were allowed to be real or significant, according to the scales and systems of modernity. We will need to dance again with the rhythms of cosmology, to be carried by the kind of stories and images in whose company – as the mythographer Martin Shaw would say – a universe becomes a cosmos. We will need to remember that we are not alone and never were, that we are part of a world of many worlds, only some of which are human. And we will need to rediscover that any world worth living for centres not on the vast systems we built to secure the future, but on those encounters that are proportioned to the kind of creatures we are, the places where we meet, the acts of friendship and the acts of hospitality in which we offer shelter and kindness to the stranger at the door. In this way, even now, there may be time to find our place within the vastly larger and older story of which we always were a part.

footnotes

1 Ben Okri, The Freedom Artist (Brooklyn: Akashic Books, 2020), 211.

2 Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2021).

3 Federico Campagna, Prophetic Culture: Recreation for Adolescents (London: Bloomsbury, 2021).

4Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

About the article of Dougald Hine, with no disrespect intended. It is not clear to me at all as to what is the point of the article. Is it a rationalization for not doing all one can, to prevent a dystopic world, perhaps a global totalitarian one? Is he suggesting that we must accept that civilization as we have known it is finished, so we should let it die as gracefully as possible? Please advise.