The Practice of Ecological Mentalizing

We live in a time when humanity has become profoundly estranged from its natural origins. Our minds and ecosystems alike bear the marks of this rupture. The ecological crisis and the collapse of biodiversity are no longer distant warnings, but present realities. While technological advancement and urban living have brought benefits, they have also distanced us from our place in nature. Along the way, we’ve lost something essential: a sense of meaning, of belonging, of spiritual connection — to ourselves, to others, and to the living world.

Is it possible to restore that connection? One emerging path lies in what I call ecological mentalizing — an integrative approach that draws from animistic traditions, psychological theories of mentalization, depth psychology and the latest insights from neuroscience. It offers a vision not only for ecological healing but for the restoration of our humanity in its fullest sense.

The concept of mentalizing refers to our uniquely human capacity to understand and interpret the inner experiences of others, to perceive minds behind behavior. This capacity is foundational to empathy, emotional regulation, and trust. The term was developed in clinical psychology, first by French psychoanalysts and later especially through the work of British psychoanalyst Peter Fonagy and his colleagues, who explored how early attachment experiences shape our ability to reflect on feelings, intentions, and perspectives. Mentalizing is what allows us to see others as persons with agency, emotion, and thought — not simply as objects.

“Is it possible to restore that connection? One emerging path lies in what I call ecological mentalizing — an integrative approach that draws from animistic traditions, psychological theories of mentalization, depth psychology and the latest insights from neuroscience. It offers a vision not only for ecological healing but for the restoration of our humanity in its fullest sense.

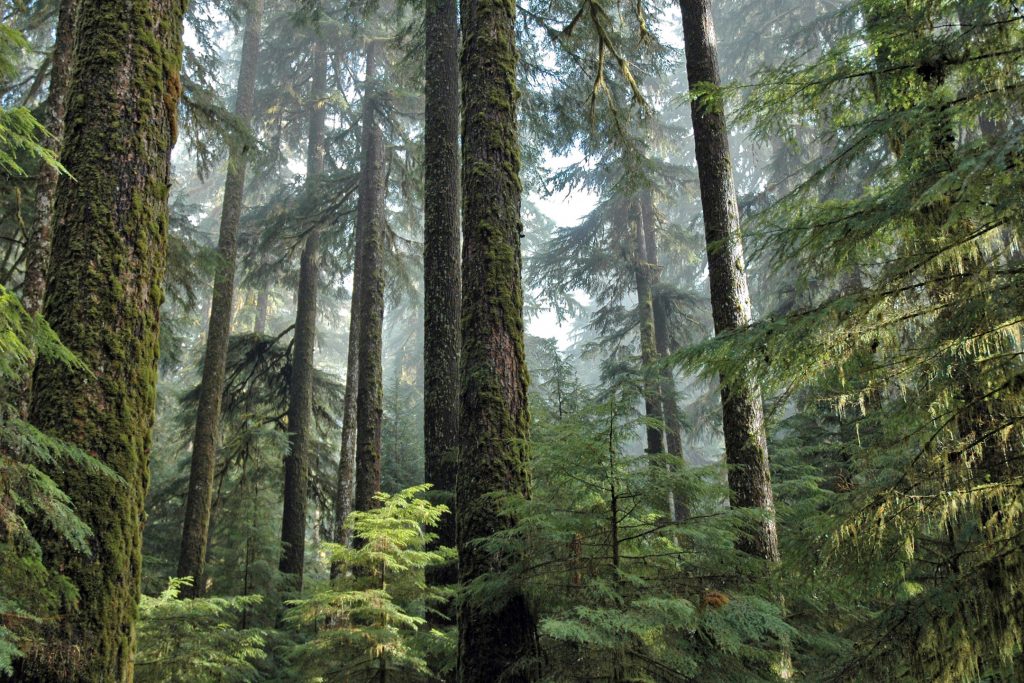

But what happens when we extend this capacity beyond human beings? What if we began to perceive trees, rivers, animals and whole ecosystems as subjects with their own kinds of awareness, needs, and intentionality? This is where ecological mentalizing begins. It invites us to re-inhabit the relational field of life with openness, imagination, and reverence.

The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, writing in the early 20th century, observed that the nature-bound human-animal within us longs to be integrated with modern consciousness. He warned that the loss of this integration could lead to psychological and societal breakdown. Today, we see this in the rising tide of mental health issues, ecological destruction, and a pervasive sense of purposelessness. The disconnection from the natural world is mirrored in a disconnection from the self.

Ecological mentalizing is not about romanticizing the past or rejecting science. Rather, it offers a framework that honors both our symbolic, intuitive ways of knowing and the analytical strengths of modern science, helping us recover our sense of place within the greater whole. It brings together depth psychology, evolutionary biology, contemplative wisdom, and environmental philosophy into a coherent vision for reconnection.

The Roots of Ecological Mentalizing

At its core, ecological mentalizing is a mode of awareness that perceives all of nature as sentient, relational, and meaningful. This echoes ancient animistic worldviews and those of modern-time hunter-gatherer societies, which saw all beings — human and nonhuman — as possessing soul or spirit. Far from being primitive superstition, these views reflect a deep intuitive logic: the human brain is wired to detect intention, agency, and emotional tone in the environment.

Developmental psychologists have shown that even infants interpret the world in social and intentional terms. We come into the world prepared to relate, to read signals, to infer subjectivity and to respond to subtle cues. Ecological mentalizing builds on this innate capacity by reawakening our sensitivity to the more-than-human world. Through practice, ritual, and deliberate attention, we begin to hear again the voice of the forest, the presence of animals, the whispers of the wind.

The neuroscientist and philosopher Iain McGilchrist has argued that the two hemispheres of the brain offer distinct ways of engaging with the world. The left hemisphere is narrow, focused, mechanistic and analytic; the right is broad, relational, systemic and meaning-oriented. Our culture, he suggests, has become dominated by left-brain modes of thought — favoring control, categorization, and utility over presence, intuition, and reverence. This has implications not only for education and governance, but also for how we perceive the natural world.

To restore balance, we need to reclaim the symbolic imagination — the capacity to find meaning in stories, myths, rituals, and dreams. Jung believed that our collective unconscious contains archetypal images that connect us to all of evolutionary history. Or to put it simply, to Nature. Ecological mentalizing taps into these deeper layers of knowing and invites them into conscious awareness. It acknowledges that part of our psyche still lives in the forest, still listens for the howl of wolves and the cycles of the moon.

What It Means to Be Human

As a species, humans are not better than others, but we are distinct. Our social brain, especially the highly developed prefrontal cortex, gives us extraordinary abilities for cooperation, empathy, and reflective thinking. But we also carry within us ancient survival systems. Whether we respond from love or fear, openness or defensiveness, often depends on whether we feel safe.

When we feel secure enough, we are able to mentalize, to reflect on our own and others’ inner worlds. This capacity has always been central to human flourishing. But it is not limited to relationships with people. When we extend mentalizing to animals, forests, rivers and elements, we begin to relate to them as subjects — not objects. We move from exploitation to relationship, from domination to reciprocity. This shift may seem subtle, but it changes everything.

We have been taught by the worldview of natural science to never anthropomorphize the other-than-human. While it is true that we should not simply project human-identical qualities onto animals, trees, or rivers, this caution has led to an overcorrection – or more truthfully, tragic severing. In our effort to avoid anthropomorphism, we have also failed to acknowledge the subjectivity, otherness, and personhood of the more-than-human world. Yet it is precisely this capacity — to perceive sentience and intention in our surroundings — that has been fundamental to human survival and cultural evolution.

As anthropologist Nurit Bird-David and others have shown, in animistic cultures, relationality with non-human beings was not metaphorical but a way of navigating and co-existing with the world. Mentalizing the more-than-human was not a mistake, but an adaptive strategy, shaping kinship systems, ritual life, and ecological knowledge. Our ancestors knew how to live among persons who were not people, but who mattered just as deeply.

To be human in the deepest sense may mean reawakening that capacity — to sense the presence of an other, even when it is not like us. This is not projection, but recognition. Recognition opens the door to ethical relationship, to mutuality, to reverence.

Modern Animism for a Disconnected Age

What might it look like to live as balanced human-animals today — not returning to the Stone Age, but honoring what is essential in our nature?

We can begin by returning to the body. The body is not separate from nature; it is nature. And yet, in modern culture, many of us live in a state of disembodiment, disconnected from sensation, instinct, and intuition. When we live from the neck up, we cannot truly feel our place in the living web. Practices such as somatic therapy, dance, meditation, and immersion in wild places can help us re-inhabit our physicality in a way that supports attunement with the Earth.

We can also reclaim our social instincts. Humans are not built for individualism; in fact, it has become very toxic for us. We need community, ritual, shared story — not as luxuries or spiritual hobbies at retreats, but as biological necessities. The dominance of competitive, isolated ways of living erodes the very conditions in which our nervous systems can be well. Mentalizing thrives in contexts of trust, safety, and co-regulation.

A sense of safety is foundational. Without it, the brain defaults to survival mode — fight, flight, freeze. In this state, we cannot mentalize, cannot reflect, cannot feel the subjectivity and therefore presence of others. Creating environments of trust and co-regulation is essential for ecological mentalizing to take root. This may mean rebuilding local networks of care, redesigning institutions around belonging rather than control, and centering practices that foster embodied presence.

We must also embrace difference. Ecosystems thrive on diversity. The same is true for human societies. Rather than forcing conformity to narrow norms, we can learn to value the unique sensitivities and gifts that each person brings — recognizing that variation within a species is key to its resilience. Neurodiversity, cultural plurality, and spiritual multiplicity are not obstacles but resources for collective flourishing.

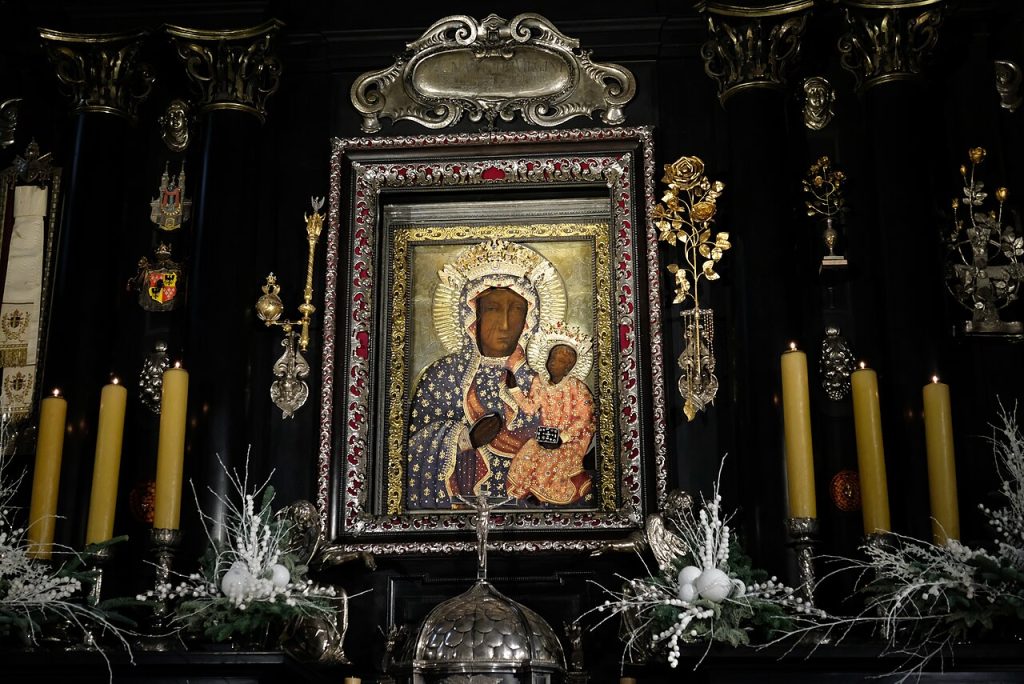

Finally, we need to reintegrate symbolic and spiritual ways of knowing into our culture. Intuition, creativity, art, and ritual are not outdated relics — they are vital expressions of human nature. When we deny them, we fracture our wholeness. Ecological mentalizing reclaims these dimensions, not as sentimental add-ons, but as essential ways of relating to life. Through poetry, prayer, and presence, we remember that we are participants in a larger unfolding.

A Society That Sees Others in Nature

Imagine a society that regarded the natural world not as a backdrop or resource, but as a web of conscious relationships. A culture that taught children not only to think critically, but to feel deeply — and to listen for the voice of the river, the message of the trees. Education would include ecological imagination as much as scientific reasoning. Governance would be shaped by humility before the more-than-human world.

Such a shift would not mean rejecting science. It would mean expanding our definition of intelligence, of personhood, of what it means to relate. It would mean holding in creative tension the insights of neuroscience and the wisdom of ancestral myth. It would mean cultivating humans who are capable not only of analysis, but of reverence.

Carl Jung once wrote that wholeness is not achieved by cutting off parts of the self, but by integration of contraries. Ecological mentalizing invites us into that integration — as individuals and as a species. It offers a way to walk forward, not by denying our modern minds, but by reconnecting them with our ancient hearts. We do not have to choose between science and soul, because we are both.

Becoming Human Again

We cannot go back. But we can go deeper. We can remember what it means to be of the Earth. We can teach our children that value is not found only in productivity, but in presence; not only in knowledge, but in intuition and wisdom. Through stories, silence, activism, relationships, and rituals, we can remember who we are.

We are, at our core, creatures of connection and meaning. And through ecological mentalizing — through restoring our capacity to feel with and for the living world — we just might find our way home. Not to a place on a map, but to a way of being: grounded, compassionate, awake.

To become human again is to feel deeply, share minds, find meaning, and to live as if the world were alive — because it is.