Resilience

Resilience

It happened in the summer of 1998. I am alone at home. Home is a little village in the Belgian countryside. The month of August is warm. In the attic, in my study room, I am preparing for a philosophy exam. I have always been fascinated by the phenomenon of life and its ‘meaning.’ That degree in philosophy is supposed to give me answers, to help me understand what life is about. Naively, I had thought that space engineering would bring me closer to the mystery. After a few years of working in that field, it became clear that the reality I wished to explore is here on the earth and now. Not out there, light-years away.

RESILIENCE IS HANDLING PARADOXES. IT IS FINDING SIMPLICITY IN THE MOST COMPLEX SITUATIONS WITHOUT IGNORING THEIR PAINFUL AND DISRUPTIVE SIDES.

Sitting at my desk, I am reading theories about life and death. The whole thing feels a little stuck in my head as if the information is trapped there, in that upper part, without any communication with the rest of my body, or with the birds outside, the sun shining through the clouds and the farmers working in their fields. Around lunchtime, in that slightly confused mood, I leave my study room to fetch the kids. I am a young mother of three children. While I was studying, they were having fun somewhere with friends.

RESILIENCE IS HUMILITY. IT IS ACCEPTING THAT WE ARE NOT IN FULL CONTROL. IT IS SEEING LIFE AS A TEACHER RATHER THAN AS MATERIAL TO SHAPE.

On my way back home, on the highway, something happens. The children are in a state of tension between excitement and tiredness, unable to sit quietly in the back seat. They are two, four, and six years old. The tension amplifies my own state of confusion. I turn to them with the intention to restore calm. My movement is a little too fast, a little too strong and a little too agitated. In that movement, I drop the driving wheel for a second, and that second is enough for the car to change its trajectory.

RESILIENCE IS TRUST. NOT TRUSTING THAT THINGS WILL HAPPEN ACCORDING TO OUR EXPECTATIONS, BUT TRUSTING LIFE SO MUCH THAT WHATEVER HAPPENS, IT IS OK.

I intended to restore calm, but at what cost? I am not driving the car anymore, but the car is driving us, taking the four of us on its own course—a dramatic one. The accident is bound to happen. We can see it coming. We see it happening in front of our eyes. The car pitches slowly from right to left, and left to right. On the highway. At high speed. Until something reaches a limit in the car structure. Until something breaks up, projecting the car in the air. Everything is then darkness, sound, and movement.

RESILIENCE IS A CRACK. LEONARD COHEN SINGS, ‘THERE IS A CRACK IN EVERYTHING, THAT’S HOW THE LIGHT GETS IN.’ WOULD IT ALSO BE A WAY FOR THE LIGHT TO GET OUT?

The car is now standing still. I smell the disaster before I see it. A smell of fuel and burnt steel. Where are the kids? Not in the car. I look for them on the highway. I find their bodies. I take care of them until ambulances arrive. While running from one child to another, I discover strength in me. At that very moment, I feel at the best of my human capacity. I am able to love as I have never loved before. The immense pain seems to be counterbalanced by an immense sense of gratitude. Love for the kids, for the people around me (car drivers who have stopped to help), for the rescue workers. Total dedication.

RESILIENCE IS ABOUT CARING RELATIONSHIPS. IT IS ABOUT A LEVEL OF CARE THAT GOES BEYOND ANY LOGIC. IT IS ABOUT LOVE AS THE GLUE KEEPING HUMAN BEINGS TOGETHER.

One child is missing. Someone shouts, “She is here!” Indeed. She is laying down on the grass away from the road. Someone says, “Don’t worry, her heart is beating, she is alive.” I believe these words of a stranger, although I see no sign of life in that little body. A young woman is standing nearby. She has witnessed the accident. I take her hand, I ask her to come closer. I place her hand in my daughter’s hand. I ask her to keep holding that little hand. “Her name is Anaïs,” I told her. “She is six. Please stay with her, keep talking to her.” Then it is OK for me to leave her and to run back to the other kids.

RESILIENCE IS GRATITUDE. IT IS BEING ABLE TO ASK FOR HELP. IT IS RECOGNIZING WHAT IS GIVEN, WHATEVER IT IS—A SMILE, A LOOK, A HELPING HAND.

That day, we were very close to death. The four of us. Today, we are all alive. Gratitude. It took me years and years to relax, to process the pain, to go through the fears, to heal the injuries. We left the hospital after a few weeks. Anaïs had spent three weeks in a deep coma, between life and death. It took her another two years to fully get ‘back to life.’ It took us a good 10 years to recover. We will never return to ‘normal.’ There is no sense of ‘normality’ after such an event. Our family, our lives, have radically changed.

RESILIENCE IS PATIENCE. IT IS BUILT OVER TIME. LIKE A PLANT GIVING FLOWERS AND FRUITS, THE PROCESS CANNOT BE FORCED. IT HAPPENS ACCORDING TO ITS OWN RHYTHM.

The shock has been such that it has deprived me of a large part of my energy. What was left was to be used mindfully, with a clear focus on essentials. At that moment, it was to support the kids through the crisis. What was the ‘right,’ useful support? Slowly, a story shaped before my eyes in which the notion of ‘respect’ had a core role. Respect as basic consideration for reality, including myself, others, life, situations. Respect as listening deeply and showing regards to inner as much as outer realities.

RESILIENCE IS ABOUT COHERENCE. IT IS A PROCESS OF ALIGNMENT: WHO AM I, HOW DO I SPEND MY TIME, WHAT DO I EAT, HOW DO I TALK, HOW DO I RELATE TO OTHERS?

That day, on the highway, while ambulances were driving the kids to hospitals, I stayed a few more minutes. The landscape was one of desolation. In an instant, the pain struck me. I realized that I was seriously injured. Oxygen was lacking, it was more and more difficult to breathe. Something then happened. Something I can hardly describe with words. It took me years and years before I was able to articulate specifics. Sometimes, I need to go back to my diary to check if it really happened. That day. On the highway.

RESILIENCE IS COURAGE. COURAGE AS THE QUALITY OF ACTIVATING THE HEART. IT IS ABOUT LEARNING TO WORK WITH FEARS, AND BEYOND THOSE FEARS, TO OPEN UP TO THE UNKNOWN.

I simply did not know how to talk about it and who would be able to understand. Such an experience is hardly describable. It includes all opposites and goes beyond the realm of words. It feels unreal and at the same time, it feels like the real stuff. It feels both warm and cold. I was lifted from my body, in a vertical movement, like in a tunnel of tiny particles. Like raindrops reflecting thousands of colors. At a high speed, with a sense of stillness. Thousands of colored particles. Further away, a warm radiating light. Intense but not dazzling. The whole experience is quiet, cool, clean, in contrast with the chaos on the highway.

RESILIENCE IS ABOUT TAKING DISTANCE. IT IS HOLDING DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES, STANDING AT THE EDGE WHERE WE DO NOT UNDERSTAND.

How can I communicate that sense of integration, fullness, unity, and peace I experienced in that moment? In the tunnel, three times, I moved up. Three times I moved down. When I finally regain normal consciousness, I am in an ambulance with an oxygen mask on my face. Landing is painful, but it doesn’t matter. Years later, after a long healing process, I reconnected with the sense of peace experienced in that very moment. I learned to approach it in the silence of meditation, in nature, in the depth of authentic relationships, in the flow of life.

RESILIENCE IS ABOUT MAKING SENSE. IT IS ABOUT LOOKING AT REALITY WITH A SENSE OF WONDER. IT IS ABOUT ALLOWING A BIGGER PICTURE TO SHAPE.

This notion of ‘peace’ became central in my life. Peace as an art, as a movement of integration of opposites. Peace as a radical opening to a wider picture. I started regarding conflicts as opportunities for transformation. From a personal perspective, I moved naturally to a collective one in which we are all together breathing the same air, illuminated by the same sun, walking on the same earth. I became passionate about relating to people as if this whole experience had brought me closer to fellow human beings. As if my story was a universal one and had brought me into the real phenomenon of life- that phenomenon I initially tried to understand through the theory of space engineering and philosophy.

RESILIENCE IS TRANSFORMATION. IT IS EXPANDING THE FIELD OF EXPERIENCE. IT IS CONTRIBUTING TO A HUMAN SOCIETY AND SERVING A BROADER INTEREST.

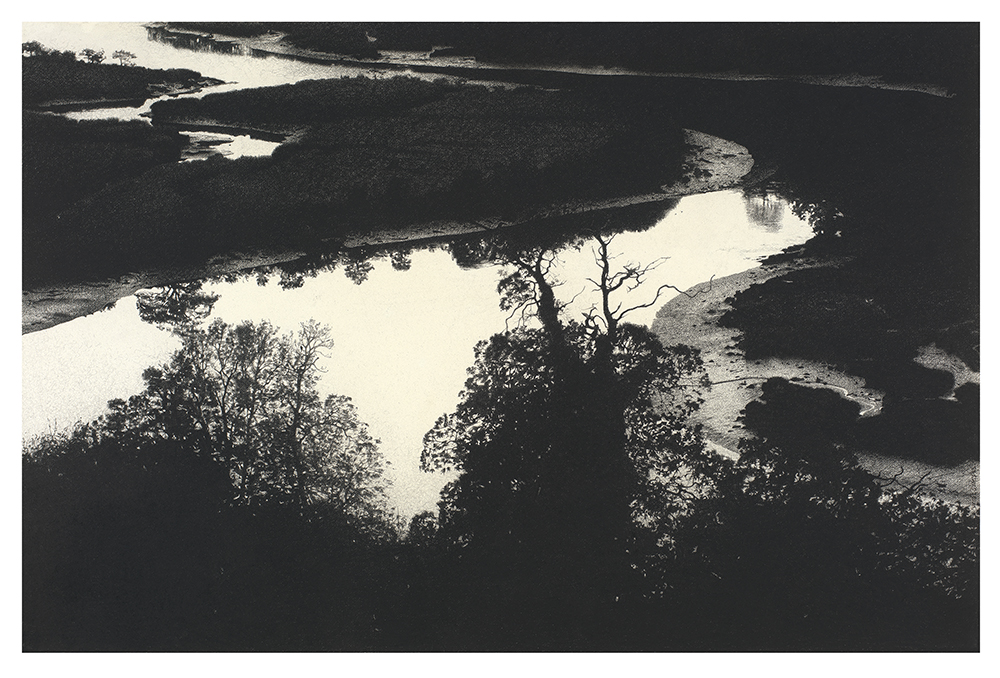

About the Images

Claude Theys paired his photos with Nathalie’s essay at her request, using meditation to connect instinctively rather than literally with her words.

Belgian by origin, citizen of the world by heart, Claude is passionate about traveling. For him, photography is the art of capturing the present moment, feeling connected with the environment, the people he encounters, and the colors that attract him. He spent over twenty years in Africa with his family and has spent much of his time in nature and wildlife.

About Nathalie Legros

Nathalie Legros holds a degree in space engineering and certificates in existential counseling and mediation. She has spent a great deal of her time in Brussels and European institutions, supporting the project of Integration and Peace in Europe. In her fieldwork with civil servants, through perspective to bring attention to ‘peace within,’ she introduced individual practices of resting (silent pauses) and collective practices of deeper inquiry and reflection (Bohm Dialogue Circles). She regards conflicts as fuel for transformation and is the author of the little book ‘Chouette, un conflit!’ for which the English translation is waiting for a publisher. In the context of the Monastic Inter-religious Dialogues (MID), she follows contemplative practitioners of different traditions in the mutual exploration of their experience. Today, she lives in a village in Belgium and gives priority to local engagement and dialogue in all its forms, including with nature.

The Migrant Quilt

The Migrant Quilt

In the late 1990s, in Northern California, we placed a photo of Liz (my late wife) and me, taken by the renown photographer Annie Leibovitz, onto a quilt. Friends and family members gathered around and hand-sewed keepsakes of their lives with Liz into the cloth: bits of jewelry, ribbons, and personal messages.

By the time the black and white photograph, created for a national “Be Here for the Cure” AIDS campaign, could be seen in magazines and writ large on subway walls, many of the people Leibovitz photographed for the campaign would be dead: the cute guy, the sparky little kid, the strong transgender woman, and the straight teenage girl. Few would make it for the cure.

People died by the thousands while the government turned a blind eye. Families mourned, shrouded in secrecy. The closest friends I will ever have grieved for each other even as they, too, prepared to die.

America as a whole seemed to shake itself awake only when thousands of AIDS Names Project Quilts were laid end-to-end on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., forming a master quilt strewn with names as far as the eye could manage—a seemingly endless landscape of unspeakable loss and undeniable love. Visitors dropped to their knees, humbled by such terrible beauty.

Now, in my backyard, another names project quilt, The Migrant Quilt Project (seen most recently at the Pimeria Alta Museum in the border town of Nogales, AZ), was inspired in large part by the AIDS Quilt. The Migrant Quilt panels will travel across the country and the artist/activist Jody Ipsen (the quilt’s originator) and Peggy Hazard (the project’s curator), along with many volunteer makers, hope for a similar impact on hearts and minds.

Women on the border often have a different take on immigration issues: more of a ‘tend and befriend’ approach, a kind of common sense, needle-to-fabric mend. The responses of women to the Migrant Quilt exhibit define the soft heart of what it means to be human. The day we visited, we watched female visitors leaving in tears.

“Docents had to go out and buy boxes of tissues,” said Jody Ipsen. “You cannot walk away from this without being moved.”

The 17 quilts in the project bear the names of people who have died each year crossing the desert in the Tucson Sector since 2000—the year the county medical examiner’s office began documenting the names of the dead, including unidentified remains). Patched together with denim, work shirts, embroidered cloth, and bandanas left behind on the desert floor, the quilts are scrappy in design and raw with truth.

Many of the bordados (embroidered cloths) stitched into the Migrant Quilts are inscribed with endearments. Contigo en la Distancia (With You Far Away) or Duerme Amor Mio (Sleep My Love) shock the viewer with familial intimacy. These personal embroideries, sometimes used as servilletas to carry food across the desert, are often blessed then sent along with a traveling family member. The embroideries have come a long way. Now they rest alongside the names of the deceased.

Each quilt represents countless lives lost on border ground, a hundred-mile strip of geography spanning two countries. The interstitial border region has morphed into a distinct culture of its own, and the quilts, with their binational contributors, fly its flag.

On the US side of the border, volunteers create each piece according to their own inspiration. Worn material migrates through the quilts and melds in the viewer’s eye. Names of the dead rise off the surface in bas-relief like rogue wildflowers pushing up through the desert floor, commanding the same kind of attention as the white crosses we see strung with wire in and around the slats of the border wall.

“Quilts have traditionally been made to memorialize loved ones who died,” said Curator Hazard. “And also, to raise consciousness.” In the Nineteenth century, women used quilts not only to raise funds for the anti-slavery movement, but to express their feelings about slavery.

Memory is the first form of resistance, and quilt-making—a primary tool of resistance and remembrance—stands the test of time. At QuiltCon 2018, the Modern Quilt Guild’s annual convention, the exhibits were honeycombed with activist quilts. The resurgence in “truth textiles” also carries on at the Social Justice Sewing Academy, which empowers youth activists for social change.

The humblest materials can communicate what cannot be said in dangerous times, can comfort the family, and can mourn the dead. Quilting, embroidery, and applique—arts of hearth and home—remain a language shared.

Two decades ago in Northern California, our fragile but fierce community took turns stitching Liz’s favorite piece of mud cloth onto a quilt. I remember the silence that day as we worked together, united in the province of memory. Craig, Liz’s long-time brother-in-arms, his large brown eyes brimming with tears, leaned over and carefully sewed a cowrie shell onto the fabric. Craig would be the next to die.

Now, on our southern border, our neighbors continue to die crossing culture. The personal is political and the political is spiritual. Rather than ask “How do we build higher walls?” we are best served, as people, to ask, “How do we meet?” and “How do we mourn?”

The root of the word memory stems from the word mourn. The devotional art of making in the service of others allows us on the US side of the border wall to touch the essence of the Other, to offer witness, and to mourn.

The Migrant Quilt Project succeeds where rhetoric fails. Pinning and stitching, working the cloth to make sure the dead are not forgotten, these quilt-makers trust that no one turns a blind eye.

The Migrant Quilts are in an exhibit at the New England Quilt Museum in Lowell, Massachusetts, through July 15. After that, they will travel to Michigan and to Illinois. See migrantquiltproject.org fo

All photos | Valarie Lee James

About Valarie Lee James

Valarie Lee James is an Artist, Writer and Benedictine Oblate on the AZ-MX Border called to contemplative arts, activism, and ecology. Find her at www.ArtandFaithintheDesert.wordpress.com

The Wanderer's Preparation in the Death Lodge

The Wanderer’s Preparation in the Death Lodge

A candidate for soul initiation knows what she has taken on. She’s preparing to die in order to be reborn. She must abandon her old home to set out for her new home. She longs for the journey but is understandably terrified by the prospect. To help her approach the edge, her guides might suggest some time in the “death lodge.” 1

The Death Lodge I

The death lodge is a symbolic and/or literal place, separate from the ongoing life of the community, to which the Wanderer retires to say goodbye to what her life has been. She may dwell there a full month or more, or, during the course of a year, an hour or two every day, or several long weekends. Some of her death lodge work will take place in the cauldron of her imagination and emotions, while other work will occur face-to-face with friends, family, and lovers. She will wrap up unfinished emotional and worldly business to help release herself from her past.

In her death lodge, she will see that the life she is leaving has contained both joy and pain, success and failure, love and the absence of love. Some of the central people in her life have played the roles of villains or victims, others of heroes. No matter. Now all the paths of possibilities within her former life are going to converge at a single inevitable point up ahead: the ending of her old way of belonging to the world.

In the death lodge she will say goodbye to her accustomed ways of loving and hating, to the places that have felt most like home, to the social roles that gave her pleasure and self-definition, to the organizations and institutions that both shaped and limited her growth, and also to her parents or caregivers who birthed her and raised her and who will soon, in a way, be losing a daughter.

She might choose to end her involvement with some people, places, and roles. In other cases, she might only need to shift her relationship to them. Although she must surrender her old way of belonging to the world, she need not violate sacred contracts. Some contracts might have to be renewed at a deeper level. It is essential she does not fool herself: embarking on the underworld journey is not a legitimate justification for abdicating preexisting agreements or responsibilities to others.

Whether ending or shifting relationships, she will feel and express her gratitude, love, forgiveness, her goodbyes. She will say the difficult and important things previously unsaid. She may or may not visit with each person in the flesh, but she will certainly have many poignant and emotional encounters.

If her parents were not criminally abusive, she will forgive them for not being who she wanted them to be. If they are still alive, she will attempt this in person. This may be the most important and difficult part of her death lodge. She knows by now no parents are perfect nurturers and all have their own wounds. She knows that surrendering her former identity requires her to heal her own wounds to the point she no longer harbors the fantasy that her human parents will somehow become perfect (or merely healthy or responsible) or that she will find someone else—a lover or therapist—to be her perfect parent. As in her Loyal Soldier work, she must learn to relate to herself as a healthy parent to a child.

In her death lodge, the Wanderer also mourns. She grieves her personal losses and the collective losses of war, race, or gender oppression; environmental destruction; community and family disintegration; or spiritual emptiness. Not only does she cease to push the painful memories away but she invites them into her lodge and looks them in the eye. She allows her body to be seized by those griefs, surrendering to the gestures, postures, and cries of sorrow. She grieves in order to let her heart open fully again. She knows at the bottom of those grief waters lies a treasure: the source of her greater life. David Whyte writes:

Those who will not slip beneath

the still surface on the well of grief

turning downward through its black water

to the place we cannot breathe

will never know the source from which we drink,

the secret water, cold and clear,

nor find in the darkness glimmering

the small round coins

thrown by those who wished for something else. 2

Each of us has been, at times, the one who stood above a dark well and “wished for something else”—namely, that we ourselves wouldn’t have to descend into the waters of grief, that our wishes would come true without our having to suffer in the process. During the descent to soul, we surrender our comfortable lives above the waters. We enter depths so dark we fear we will die, and in a way, we will.

The Death Lodge II

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without love

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought:

So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.

Whisper of running streams, and winter lightning.

The wild thyme unseen and the wild strawberry,

The laughter in the garden, echoed ecstasy

Not lost, but requiring, pointing to the agony

Of death and birth.

— T.S. Eliot 3

Most people enact a vision fast with an intention, or at least a need, to grieve significant losses. The death lodge is an essential preparatory practice.

A man in his mid-twenties came to grieve his father’s death that occurred when the young man was eighteen. Thomas, who himself became a father at seventeen, had many questions about what it meant to be a man. He grieved his father’s premature death, his uncertainties about his own fatherhood, and his sense of being deprived of the cultural rituals that might have helped him become a man earlier and more completely. Like everyone, his time in the death lodge included sorrow for what might have been.

Many people embark on a vision fast or on the descent to soul, more generally, in part to say goodbye to an identity they have outgrown, in a sense to attend their own funeral. Some write a eulogy for themselves, a farewell to the old story. Although the new story stirs inside them, they know the old one must first be laid to rest.

Anita, a professional and mother in her forties, came to formally mark her empty nest as her youngest entered college. She wanted to honor the end of twenty-one years of soul work, the labor of love of raising two fine young men. And then there were the two failed marriages, an alcoholic father, and a mother who died when Anita was four. In the death lodge, she also said goodbye to her way of being a psychotherapist; she knew a more creative and artistic path awaited her.

In the two years before his first vision fast, Steve, a young psychiatrist, lost his mother and brother, his career fell apart, and he, at long last, severed his abusive relationship with alcohol. He came to formally end his decade or more of what he called “being dead,” staggering through a lonely life of despair. In his death lodge, he finally experienced his rage at his dad for the years of brutal criticism and ridicule- and all the grief waiting in line just behind the rage.

Tom, a Harvard M.B.A. in his forties, made millions as a successful (and ruthless) corporate mercenary. He found himself with a trophy home and boat, a second ruined marriage, no idea of who he really was, and his only son suicidal at the end of high school. Stunned to find himself bereft of the American dream, he came to his vision fast recognizing he and his son were facing the same crisis of meaning, one at the threshold of emancipation, the other at midlife, but both with the opportunity for true freedom. Tom, who was beginning to discover the fine human being beneath his former corporate persona, had much to surrender in his death lodge: buckets of tears and everything he once thought life was about.

In the death lodge, you loosen your grip on your former identity and world. You cut the cords, then gingerly step along the narrow ledge above the abyss, your back to the crag. At last, you turn and extend your arms against the half-truths of the old life, your fingers lightly pushing away.

To relinquish your former identity is to sacrifice the story you had been living—the one that defined you, empowered you socially, and limited you. This sacrifice captures the essence of “leaving home.”

Once you have in earnest entered the journey of soul initiation, you begin to live as if in a fugue state. Imagine: after developing an adequate and functional identity, you now have become as if amnesic, dissociated from your prior life. But, unlike the victim of amnesia, your goal is not to discover who you used to be, but rather who you really are.

Your time in the death lodge grants freedom. Untied from the past, you dwell more fully in the present, more able to savor the gifts of the world. You find yourself projecting less and seeing the world more clearly and passionately. You experience a deepened gratitude for the richness of life, for the many opportunities that await you.

Confronting Your Own Death I

The courageous encounter with the unalterable fact of mortality supplements and extends the activities of the death lodge. In the death lodge, you made peace with your past and prepared to leave behind an old way of belonging to the world; you prepared for a “small death.” Now you have the opportunity to prepare for your inevitable and final death, look your mortality in the eye, and make peace with the brutal fact that, ultimately, you will have to loosen your grip on all of life, not just a life stage.

On September 11, 2001, Ann Debaldo was leading a journey in a remote corner of Tibet, unaware of the events unfolding in the United States. But like most Americans that day, Ann had the opportunity to become more intimately acquainted with death. At 14,000 feet in the Himalayas, Ann witnessed the extraordinary Buddhist ceremony of sky burial while, elsewhere in the world, people witnessed another kind of sky burial in the air over New York City.

We were camped near Drigung Til Monastery. The evening before the sky burial, we attended the powa practice. A specially trained lama sat in front of the four corpses, each of which was folded into a small bundle and wrapped with blankets tied with ropes. Offerings to the monks—bags of flour and other staples—were taken off the horses by family members who had carried the bodies here, a journey of many days, perhaps weeks. The lama went into a profound meditation and at regular intervals made a loud sound- phat!– to open the crown chakras of the corpses, allowing any remaining life force to depart. We sat in silence as the offerings were casually divided among the monks and the lama performed his task.

Very early the next morning, we walked silently and slowly up to the hilltop where the sky burial would take place. I walked with an elderly man whom I had earlier tried to discourage from coming to Drigung Til. He was ill-prepared to handle both the altitude and the primitive camping, yet in Lhasa it became clear to me that attending the sky burial was what his journey was all about. The group moved ahead and we took the less steep pathway, his labored breathing increasing with each step. As we reached the top, a monk gently untied the ropes on one of the bundles and removed the blankets, revealing a very old woman with limbs lying at impossible angles to her torso. A great calm came over me. The old man gasped and almost fell. To prepare the food for the vultures, the monk flayed the meat and then crushed the bones into grain on a great round stone. We were so close that bits of flesh landed on our clothes. The old man was unable to stand, and so we moved even closer to lean upon the stone wall next to the monk. I felt a warm strength as I supported my companion’s weight, understanding how close he was to his time of departing this life. I could feel his heart beating and his heavy breathing as the huge golden vultures edged nearer to their breakfast.

Each corpse was similarly handled. Wave after wave of vultures descended upon the meat and grain until abruptly, there was nothing left. I watched, filled with a strange joy as the great birds lumbered down the hill before jumping into the sky and soared away over the valley toward the snow peaks in the distance. Oh, to fly freely—man becoming bird! What is death but an opening of a door?

We walked in silence down the steep hill toward the monastery where the monks began parading and chanting to the sounds of their great long horns and drums. As I sat in the hot sun, I shivered so hard I almost fell off the wall, my mind reeling. It was difficult to think and perhaps consciousness was briefly lost. Then, in my belly, I felt the presence for the first time of a great mountain of peace and silence—a feeling of solidity and calm strength, quite new to me. We left the monastery, each of us affected in our individual ways, but certainly forever changed by our visit to the burial grounds.

Confronting your own mortality, intimately and bravely, imagined or vicariously witnessed in graphic detail, is a powerful soulcraft practice, possibly an essential one. The embodiment of soul that you seek is not going to go far if you are living as if your ego is immortal. Put more positively, your soul initiation will be rich to the extent you can ground yourself in the sober but liberating awareness of limited time. This very moment may be your last.

Confronting Your Own Death II

The confrontation with death is an unrivaled perspective enhancer. In the company of death, most desires of adolescence and the first adulthood fall away. What are the deepest longings that remain? What are the surviving intentions with which you might enter your second, soul-initiated adulthood? The confrontation with death will empty you of everything but that kernel of love in your heart and your sincerest questions. It is in such a state of emptiness and openness that we hope to approach the central mysteries of our life.

As a Wanderer, it is a good practice to look Death in the eye. Contemplate your unavoidable aging and inevitable demise, “the bitter unwanted passion of your sure defeat,” as David Whyte puts it. During your wandering time, you might visit cemeteries or mortuaries, and sit there for hours or days and really look and listen and feel and breathe the thick air in those places. You might learn the traditional and sacred practices of those who prepare a body for burial or cremation.

Perhaps you will volunteer for hospice and spend hours gazing into the eyes of those who lie at death’s door, your heart stretching ever wider, both your eyes and your companion’s peering over the edge of life’s cliff. In hospice, you will witness the dying process, life ebbing away, and the moment of death itself. You will see people die well and not so well. You will see how families deal with death or refuse to deal with it. You will see some people embrace their deaths and celebrate their lives, and others die bitter and angry, never having acknowledged they were dying.

Discuss death with your guides and fellow Wanderers. Sit in councils specifically dedicated to talk of death. While alone, wonder about death, wander with it, wrestle with it. Feel its presence, both emotionally and physically. Ask yourself and others questions about death and share your feelings and speculations. Along with Mary Oliver, rhetorically ask, “Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?”

Should you suffer the loss of a loved one, permit the force of that death to transform you with its weight, fully feeling and expressing the immense grief, allowing it to irrevocably alter the world and your place in it. And should your people suffer an unthinkable loss at the hands of others (as on September 11, 2001), surrender to your anger and grief, but also look for the enemy of life within, the elements of self not in alignment with life. Find where death lives inside.

When you progress from one stage of life to another, celebrate the promises and possibilities of the new, but do not shirk from grieving the little deaths inevitably accompanying these shifts—the death of youth, unrealized dreams, cherished hopes, bedrock illusions.

Gradually, you will come to live in the light of death, not morbidly but with an increasingly joyful appreciation for this moment and your presence in it. You will cling less and less to who you are and how you are and become more attuned to your destiny, with allegiance to neither your social past nor the current accommodations of your personality.

As Carlos Castaneda was taught by his teacher, the Yaqui sorcerer don Juan, ask death to be your ally, to remind you, especially at times of difficult choices, what is important in the face of your mortality. Imagine death as ever present, accompanying you everywhere just out of sight behind your left shoulder.

In these ways, make peace with your mortality. One day you will find you are not so attached to your life being just one certain way. Then you will be better prepared to converse with soul and its outrageous requests for radical change.

With any soulcraft practice, the Wanderer seeks to put his ego in a double bind, a checkmate that makes it impossible to continue the old story. Confronting the inevitability and ever-presence of his death loosens his grip on his routines, dislodges his old way of obtaining his bearings, ushers him to the threshold beyond which lies the unknown. Horrified, he discovers he must give up everything in order to get what he really wants, with no guarantee of success or even of surviving his quest.

He is like a dog playing fetch when someone suddenly throws the stick into a bonfire. Stunned, the dog stares into the flames with big eyes. The soul wants the Wanderer to jump into that fire. The Wanderer’s deepest instinct for survival is counterbalanced by his passion for the quest. What will he do?

By confronting the truths held by death, the Wanderer gradually relinquishes his illusion of immortality and finds himself with a new hope for the world. He sees all things must change to evolve. He sees that death and impermanence provide hope for an evolving universe.

References

1 Steven Foster and Meredith Little introduced me to the death lodge as a practice in preparing for a vision fast. See Roaring of the Sacred River: The Wilderness Quest for Vision and Self-Healing (Big Pine, Calif.: Lost Borders Press, 1997), p. 34.

2 David Whyte, “The Well of Grief,” in Where Many Rivers Meet (Langley, Wash.: Many Rivers Press, 1990), p. 35.

3 From “East Coker,” in T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1977), p. 28.

Adapted from Bill Plotkin, Soulcraft: Crossing Into the Mysteries of Nature and Psyche (New World Library, 2003).

About the images:

By William Blake, selected from: Europe: a Prophecy, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and Milton: a Poem, To Justify the Ways of God to Men.

About Bill Plotkin

Bill Plotkin, PhD, is the author The Journey of Soul Initiation. As a depth psychologist, wilderness guide, and founder of western Colorado’s Animas Valley Institute, he has led thousands of women and men through nature-based initiatory passages. His previous books include Soulcraft, Nature and the Human Soul, and Wild Mind. He lives in Durango, Colorado and you can visit him online at http://www.animas.org.

Three Poems

Three Poems

Editor’s note | I met Lee in the waning summer of 2013 on Martha’s Vineyard. Over dinner, we discussed life things, including our love of dogs and Lee’s experience as a cancer survivor. I was moved then, and now, by Lee’s softness and grace. At this time, he is facing a terminal diagnosis with the same deep quality of equanimity.

He says, “cancer is a spiritual disease, because it forces one to shed much of the garbage we bury our spirits under in our day-to-day lives, and return to what is really important — friends, family, love, forgiveness, compassion, and acceptance. I must admit, I am not in a hurry to get there, but I am looking forward to the transition and journey into another dimension. And I have been fortunate to have had a life lived in one of the best of times.”

Drawing on his love of art and poetry, spiritual teachings of the East, and Christian mystics, including Meister Eckhart and St. John of the Cross, Lee has shared the hope that his acceptance of the cancer and final diagnosis without anxiety or fear might benefit others who face a similar trial. I’d like him to know that it does. And will continue to do so.

His prolific outpouring of words, as Martha’s Vineyard’s Poet Laureate Emeritus can be found here.

Statement by the poet

As a spirit traveling through matter on a journey towards an unknown event horizon, poetry has been a record and exploration of the inner experience, thoughts, and feelings of this human voyage in a world that is beautiful, mysterious, radiant, and at times terrifying. I learned early that language is a living animal that must be ridden naked and bareback, allowed to go where it wants without forcing it in another direction. Then writing becomes a state of meditation, prayer, revelation, channelling, and exploration of the unsayable that lies behind our daily lives. Over time I learned enough craft to get myself out of the way, and let the poem carry me and inform me. Most of the poems come as gifts, for which I am grateful, and I often find myself surprised I am allowed to be the vessel through which they pass into this world like wayward children.

The Day the World Ends

The day the world ends insects will sing psalms and hymns,

extinct animals will forgive the sins that killed them,

and broken dreams instead of shovels will fill the palms

of gravediggers whose secret philosophies stay unspoken

until theatrical sacrificial scenes are reenacted on boot hill.

Mountains will move imperceptibly towards the sea,

convicts escaping barren plains into horizons

free of constraint or restriction, and boulders tumbled to shore

will become petrified saints crucified by cormorants

drying their wings in whispering prayers of a dying sun.

On the day the world ends we will lie together beneath

the orchards of senses and stare and tremble and breathe

pale dusk air as petals and leaves of moonlight’s white orchids

fall on our lips and eyes, and all we wished but never said,

those things we knew but couldn’t name, will rise

from the Earth around us, a swarming beatitude of bees

sweeping us towards what life remains after the day the world ends.

Attestation

Despite unwanted endings and disasters

we have created, today I will attend

the ceremony of my life with compassion

in a ritual of love for a dying world.

In devotion I will not cry for any except

the innocent — the poor, the children, the animals —

who no longer have gods or myths to save them.

I will bend willingly before the altar light

that emanates from those to come, who will know

the catastrophe of our apathy, greed, and technology;

and I will praise the ones who suffer pain and hunger,

yet still resist; who bind their hardships brightly

with tears and songs and laughter, despite

the wounds and scars mapping all life that exists.

I will bleed internally with the joy of living,

with the memory of those who helped me

make it through the wilderness, a journey of

radiance, terror, and love, as the road bleeds

distances and vistas in a thousand footsteps home.

I will bleed the language of lilacs and orchids,

nettles and burrs, for everyone who shares a dark unknown,

and I will graze like a gazelle on each heartbeat

and breath my body takes, on the vibrating green veldt

of shimmering summer light left in imagination,

and the deep blue-gray sea light in the chill of autumn,

and the amorphous winter animals of prowling snow,

and this energy that flows with compassionate grace

through everything we experience, are, touch, and see.

Song

There is a song animals sing when they are threatened,

frightened, hurt, or wounded; and another

when they are left alone,

a song of gratitude for simple things

that brings forth all the songs their young will sing

in midnight haunts to the other side

of the Mountains of the Moon,

as they roam over earth filled with twilight

until dawn’s silver ladders of light

bleed through the

veined, blue mist of distant foothills.

And without grievance, a song of grace

for form, the skin and bones they bear

through life without complaint;

and for shelter, food and water, and every

hidden haven safe from slaughter;

and for the very air they breathe in singing

that emanates without restraint

through all the world’s hardships and sorrow,

as they disappear from our lives leaving

only these echoing Kyries their bodies sang

in sadness, radiant, even in the dying.

About Lee McCormack

Born 1945 in Seymour, Indiana, Lee McCormack is a writer, guitar-maker, and master carpenter/builder residing on Martha’s Vineyard since 1972.

A founder of The Savage Poets of Martha’s Vineyard, he was elected Martha’s Vineyard First Poet Laureate (2012-2014) by the Martha’s Vineyard Poetry Society, and was a finalist in the Montreal International Poetry Prize in 2013-2014. Lee studied intensively with Galway Kinnell, Sharon Olds, Charles Simic, Robert Pinsky, Thomas Lux, and Peter Klappert.

Kito Mbiango | The Power of Art to Drive Action

Kito Mbiango | The Power of Art to Drive Action

Kito Mbiango’s work speaks nostalgically to our primal intelligence, engaging us in a conscious reflection about our collective evolution. His Climate Change Collection is a response to the accelerating environmental degradation we are facing and have imposed upon nature and all wildlife. The artist’s goal with this collection is to shift the traditional climate change narrative of impending doom to a more positive one of reverence and deeper reflection through ‘embodied cognition.’ In this series, he invites viewers to experience these awe-inspiring feelings of interconnectedness with nature through his vivid, interposed imagery. In doing so, he seeks to spark conversations across generations and geographies to spur collective action and draw attention to the dire need for restoring balance with nature.

It is said that we are experiencing ‘climate grief’ or ‘ecological grief’ which captures the feelings of loss, anger, hopelessness, despair, and distress caused by climate change and ecological decline. This feeling of loss is impacting our psyches and mental health, but also making many realize that this means we will all need to make changes in our lifestyles and eating habits, which can lead to further denial and paralysis.

In turbulent times, we often turn to the artists and creatives to nurture our inner selves and help us construct and imagine new realities. As Leonardo DaVinci said, “Art is the queen of all sciences, communicating knowledge to all the generations of the world.” Art and culture thus have an immense role to play in educating and mobilising civil society towards climate action. “When we look around our cities,” observes Mbiango, “we are bombarded with ads for consumer and luxury products. This push to consume is what has created this climate disaster to begin with.” In his view, we need to use similar tools and thinking to reverse this trend, impelling people to collective action.

“We are missing the visual and cultural language needed to communicate about the climate, which can empower families, communities and influencers to demand change and resources from their policymakers and governments,” says Mbiango. “At its core, it is about reminding us of our organic unity–and about respect, reverence and love.”

Kito Mbiango finds inspiration in esoteric concepts, vintage photographs, and scientific illustrations. He transforms this material into a new language in which colors, textures, and geometry are used to reflect the eternal dance between man, woman, and nature. He implicitly understands the importance of finding a visual voice or resonance. He does so by a focused meditation on a particular theme. He then transfers and blends symbols and images onto fabric, canvas, wood, and recycled materials. Each medium he uses involves meticulous studies of layering and light, evoking ancestral spirits and voyages through time.

Rooted in Social Justice

The sensitivity of his work stems from Mbiango’s African roots—his father was President of the Supreme Court of Congo and his mother was a nurse. His grandmother, a master in ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging was a major influence. They shared a passion for geology and collecting minerals together when he was young. This rich cultural exposure led to a deep veneration for the land, indigenous wisdom, and how it should inform our collective future. He pays tribute to timelessness—where imagination and reality intersect.

Mbiango divides his time among Brussels, New York, and Miami. He has mastered his own technique utilizing multiple production methods, including image transfer and mixed media assemblage, applied meticulously by hand. His body of work explores themes encompassing memory, history, and socio-political realities. Ultimately, they reflect a collective yearning for transcendence.

The Artist as Futurist – Towards a Collective Consciousness

Mbiango’s work is informed by a deep passion for innovative thinking and the work of futurists like Elon Musk, Buckminster Fuller, and theologist Teilhard de Chardin who set down the philosophical framework for planetary, net-based consciousness over 50 years ago. Chardin foresaw the development of the internet, but described it as a noosphere—literally, “mind-sphere,” or a thinking layer containing the collective consciousness of humanity which will envelop the earth. He realized that everything around him was beautifully connected in one vast, pulsating web of divine life. He likened this global infrastructure to “a generalized nervous system” that was giving the human species an “organic unity.” Mbiango’s artistic practice reflects these rich notions of human connection emerging. He intuitively incorporates elements of ancient knowledge, through imagery and symbols, which form part of his vast archives. This organic weaving of ideas, materials, and processes creates indefinable works that are emotive and thought-provoking because they deliberately transcend recognized classifications.

Mbiango has been recognized for his pioneering work by The Institute for the Future, Palo Alto and his work has served to support global advocacy across the private and public sectors including with BNP Parisbas, Women Deliver, The World Bank’s Climate Investment Fund (CIF), UNICEF, UN Women, Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation the David Lynch Foundation and the World Economic Forum.

Mbiango has been recognized for his pioneering work by The Institute for the Future, Palo Alto and his work has served to support global advocacy across the private and public sectors including with BNP Parisbas, Women Deliver, The World Bank’s Climate Investment Fund (CIF), UNICEF, UN Women, Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation the David Lynch Foundation and the World Economic Forum.

He recently took his activism to the streets on digital screens across New York City and in the iconic Oculus in the World Trade Centre. He hopes to incite waves of change by getting others of all ages and backgrounds to bring their creativity and passion in support of the climate movement.

Artist's Statement

About Jill Van den Brule

Jill Van den Brule is a humanitarian and social entrepreneur. She co-founded MPOWERD, a B Corps that makes the solar powered Luci lantern, which has impacted millions of people all over the world – providing clean, reliable light to those living without access to electricity. She was part of UNICEF’s emergency response team in post-earthquake Haiti and has launched many global campaigns including with the UN Sustainable Development Goals Advocates, an eminent group of global leaders focused on SDG implementation. She represented UNESCO in the groundbreaking UN Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and her work has been published in various international media outlets.

Art in a Time of Catastrophe

Art in a Time of Catastrophe

Featured image | Sketchbook drawing, Sarah Gillespie

“What can poetry say in a time of catastrophe?” asks the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, referring to the catastrophe of Palestinian exile, the Nakba. His question inspires us to ask the same question about the place of creative art at this time of ecological catastrophe: climate change, the destruction of ecosystems, the sixth extinction of non-human species.

We borrow Darwish’s word ‘catastrophe’ with care. We might have used ‘crisis,’ but a crisis is a turning point, often used to refer to that point in illness when the patient may recover or not. There cannot, however, be a simple ‘recovery’ of planetary health; the changes that have been wrought to Earth’s systems are too extensive. A catastrophe, in contrast, is an overturning, a reversal. Whatever we do, the oil has been burned, the carbon is in the atmosphere, the living world is impoverished. We are at the end of the civilization as we have known it; things are not going to stop falling apart. Human—Western—culture is overwhelming the great forces of nature and, in turn, nature will overwhelm culture.

At such a time, are the arts irrelevant, a luxury? To the contrary, they have an essential place both in grieving for what is lost and in imagining new human possibilities. Facts and figures don’t influence people directly—all science has told us about climate change has had little impact. It is the stories we tell ourselves, the metaphors we draw on, that create our world. The mess we are in reflects the stories that have dominated Western culture: stories of human supremacy, stories that separate humans from Nature, that emphasize economic growth at the expense of human and ecological wellbeing. Stories that we ‘rational’ creatures no longer need stories. Whoever can change these pervasive narratives can change our core beliefs—for better or for worse. Visual art, prose, poetry, music, drama can all help provide space and imagination for new stories to emerge and artful means to express them.

And yet, we don’t know what new stories we might tell. We modern humans do not know how to respond to the catastrophe of our times. The old stories have lost their power; there is a shared, yet scarcely articulated, sense of profound unease. As Leonard Cohen puts it, “The blizzard, the blizzard of the world | Has crossed the threshold | And it has overturned | The order of the soul.”

Then, there is art as beauty. Beauty can rip the fabric of the taken-for-granted world, create an opening to a different experience. And art may also offer us a place of beauty that can sustain us through darkness, even make beauty out of that darkness. This is what the poet John Keats was pointing to when he celebrated ‘negative capability’: “being in uncertainties, Mysteries and doubts, without any irritable reaching for fact & reason.”

In our own art and writing, we seek to experience and communicate a particular story—a story which restores a sense of the living presence of Earth and ourselves as a part. How do we learn to listen, to hear the voices of the river and the trees once again? How do we move away from the conceit that humans are special, separate, and learn to take our place within the community of life? And as we learn how to do this for ourselves, how do we draw on our creative practices to communicate this possibility to our fellow humans?

Sarah describes working outside with a sketchbook: “After a period of settling, several hours into the drawing, I find myself becoming absent. In quieting myself, something shifts. Now less full of my ‘self,’ I sit still, looking, breathing, drawing. On a really good day, the presence of the tree, or the nest, or the light on the water, whatever it is I am making a study of, comes up and towards me. There’s nothing metaphysical or theoretical about this; it is a physical feeling of empathy, of absolute sameness. I find this an enormous relief. It is my way in. Having some sense that we are not separate, that is our biggest hope.”

Peter’s writing practice is similar. “I sit for long periods in my orchard. I listen to the wind high in the trees, watch the way it spins eddies across the meadow grass, follow the local jackdaws as they flock noisily across the sky. Sometimes, I am captured by something so simple that it draws me in—a dewdrop on a twig one misty morning, the pattern of light and shadow cast on the wall, the profound silence that appears to lie behind all sounds. Watching, listening, scribbling notes: if I am patient, I may find that my sense of self has become diffuse and uncertain, with no clear boundaries between in here and out there.”

Working in a studio is different, says Sarah. “I am inside, with doors, with learned skills and familiar materials. I can’t just put my sketchbooks out in the world and hope that they will do the same for others as they did for me sitting there. Work in the studio is the art of transformation: to make something with all the skill and years and hours that I have mustered to speak about non-separateness.” Peter adds, “Notes made outside, maybe written in the dark or on a notebook soaked in salt water, must be crafted into a narrative the speaks to a reader.”

So why, Sarah asks herself, do this in such an inefficient way, taking hours and days to make drawings, one tiny mark at a time? Surely the story could be better told with a video blog, and Instagram account. “But the materiality and the slowness of the work is more appropriate. I make gesso with bone ash and use rabbit skin size; draw with silver or burned wood; engrave on copper. I don’t use acrylics to paint or plastic to engrave. Partly because they just mean more plastic that gets washed down the drain. But, more importantly, these natural materials speak to me deeply and handling them everyday has an effect on me. It is a practice of preparation, like the Zen discipline of giving full attention to sweeping the floor.”

Peter’s process is equally slow: “I set out on two long ecological pilgrimages sailing around the western coasts of the British Isles, travelling at walking pace across the sea. Long, slow travel takes me out of the taken-for-granted structures and habits of everyday life: work, family, relationships, play, news, entertainment, all of which shape the story I play in my head and draw me into a conformity conducive to modern life. It is not easy to move across the boundaries between worlds when locked in everyday familiarity: the practical challenges of pilgrimage spin the human heart and mind into new realizations.”

So, what place art in a time of catastrophe? For us both, it is about making openings, like putting your fingers into a knot and teasing it apart, making enough space so others might share with us this precious and tenuous truth that we sometimes glimpse: that we are not separate. For if we know we are not separate, we are, perhaps, less willing to harm.

We see these as practices of humility, learning slowly—so very slowly—to take our proper place on Earth. And to offer glimpses of this to others.

This original essay can be found at the author’s blog, On Presence: Essays | Drawings available from the authors.

About Peter Reason

Peter Reason is professor emeritus, University of Bath. He links nature writing with the ecological emergency of our times, drawing on scientific, ecological, and philosophical and spiritual sources.

About Sarah Gillespie

Sarah Gillespie is an independent artist and a Royal West of England academician. With 35 years of professional practice, she makes paintings, drawings, and engravings that give primacy to the natural world.

A Cry for Help

A Cry for Help

“It is remarkable that in a society like ours, with so many advantages and such valuable resources available to it, that the rate of suicide continues to increase. . . . Clearly, we face serious dysfunction as a society—with little evidence that our situation is going to improve. But this is not a moment to despair. Instead, we could understand it’s a call to arms—or a cry for help.” – Caring, Tarthang Tulku

I like to consider myself a helper, but when our son, Jon, took his life on Easter weekend of 2019, I could no longer think of myself as a successful helper. In my own eyes, I instantly became a failed one. The truth the Buddhists speak of—that everything is impermanent—has now swept into my life. The truth of this is so palpable that it feels strange that I am still living in comfort in a heated house with a roof over my head, and that I have whole days when I forget I was unable to save my son.

And yet, in an unfamiliar way I am still trying to grapple with, I am still evolving. It is difficult to articulate, but I took a giant step closer to being able to understand the experience of parents who are separated from their children at the border. I began to feel a kinship with those who wander rootless with no land to call home, or who live in constant risk of being hurt or killed.

I am gradually learning that when you join the ranks of people who have not been able to control the most important events in their lives, any lingering indifference to the fate of others starts to drop away—like the skin of a snake that has become too tight to allow caring to grow.

Our private losses open us to the plight of others; but even in that, there are differences. A parent who has their child torn from their arms, or a person who is imprisoned and tortured, suffer untold torments. Yet there is still the hope they will see their children again. But when your son commits suicide, there is no cause for hope. The sense of finality is so unbearable that you find yourself denying what has happened, blaming yourself for it, or trying to flee into the old life you led in your comfortable house with your freedom to drive to the store whenever you feel hungry, or to schedule a date to meet a friend for coffee. (Just for the record, none of these strategies work.)

I used to be able to tell myself that I was doing enough when I was involved with a nonprofit called Friends in Time, that I cofounded with a friend who has ALS. We helped hundreds of people with MS and ALS over the two decades we were in operation. We thought of ourselves as “friends” offering help in a “timely” manner to people feeling overwhelmed by their life situations. It was clear that we were helping, making a difference, and that the recipients appreciated it. And I don’t remember ever feeling then that the suffering was so great we couldn’t help alleviate some of it. I felt I was helping; that was part of my identity.

But I also notice that I do a good job of turning the other way when confronted with the kind of suffering I feel incapable of doing anything about. For example, the growing ranks of casualties of global momentums that show no sign of slowing down. Watching the unfair advantage some wield over those who cannot protect themselves leaves me deploring my own helplessness—and I turn away. And, in the aftermath of Jon’s death, I turn away even from awareness.

I am in the grips of ignorance, one of the three poisons of Buddhism, along with grasping and aversion, which are said to propel the Wheel of Life along the difficult thoroughfares of Samsara. Looking back, I see that I ignored how much suffering Jon was experiencing. And now I am in the grips of another kind of forgetfulness. I can hardly remember how much he was in my heart during the 27 years we shared together. It’s as if a moat has appeared between the past and the present—as I imagine will happen again when each of us dies. My memories of Jon seem to be hovering out of reach, too dangerous to approach.

I am not alone in this experience. Attending Survivors of Suicide (SOS) meetings, as my wife and I have done for the past seven months, I get to see directly how survivors—when our defenses slip—carry regret, guilt, and the threadbare cloak of “what ifs” as our new companions in time.

Then, there are those who push themselves even deeper into the issue or problem. But this can give rise to an ongoing sense that we are failing to do enough. It can be a recipe for exhaustion.

I, the helper, now need help. And now I know why caring matters.

This, I think, is the third place from which to view the world’s suffering: as one who also suffers. For years, maybe I only knew how to dole out help to others, like a Pez dispenser, but now I am suddenly in need of help.

If we can only let our private suffering sink into our hearts, we are in a unique and sacred position to empathize with those who are experiencing the same or similar pain.

There are many in the same boat, especially here in the USA. In many other parts of the world, suicide rates have declined between 2000 and 2012, but the USA has seen an increase of 24 percent. For young people between the ages of 10 and 34, suicide has become an epidemic: it is now the second leading cause of death for boys and girls and for young women and men—with only accidental death claiming more lives.

Why is suicide on the rise? Is it because our planet is being treated like a carcass to be chewed upon by the boldest scavengers? No wonder a new generation feels there is little purpose to their lives, little reward for trying to connect livelihood with honorable intentions.

Jon took his own life in part because he cared so much, and he despaired that his caring mattered.

Franz Kafka may have seen this epidemic coming when he wrote: “He ate the crumbs that fell from his own table and with time he forgot how to eat at the table; then even the crumbs ceased to fall.”

As individual consciousness shrinks to preoccupation with getting our own share of the common good—without much concern for how that ‘good’ is flowing from Mother Earth, and even less concern for the illumination that makes our consciousness possible—Kafka’s vision of scrambling after crumbs is coming to pass before our eyes. As children who may not have eaten for days look on, we see container ships with their holds full of crumbs setting sail for parts unknown.

I am a writer, and so I am attracted to poetic metaphors. But of what value are they, really? Can they help bridge the chasm between those who have and those who don’t; between the desire to help and our sense that we are powerless to do much in the face of momentums that ensnare the human mind and put the least generous among us in the control room? Do they help bridge the efforts of those who act bravely in the face of injustice?

Can metaphor give us strength, or poetry help us heal? Kafka also said, “Let the face full of hatred fall on its own breast.” I take this not as an invitation for us to hate ourselves, but as a source of insight:

Unless we introduce our judgmental minds to our own suffering hearts, we will never influence the momentums that are spawning such suffering in our world; we will not be able to add the ballast of our presence to the sacred task of protecting the common good which Mother Earth is still struggling to provide to all living beings.

I’ve lost my chance to help our son see that his caring matters. And life has not yet brought into my orbit others of a new generation whom I could encourage to feel hopeful about a future we all share. But I am trying to look more closely at the people who are in my life and to see the suffering and confusion that I know is there, because so many have their own losses and must be mourning them. I am starting with myself, the one whom I have not yet learned to treat with enough kindness. Then I hope I can learn to be kind to others, guided by a deeper understanding of how it feels to receive my own kindness.

I dream of one day having something that is truly worth sharing with others, my full-hearted helpfulness. Because I know that the capacity to be truly helpful is the greatest gift that life can bestow upon us.

About Michael Gray

Michael Gray is the author of The Flying Caterpillar, a memoir, and the novels Asleep at the Wheel of Time, about whales, aliens, and humans, and Falling on the Bright Side, about his experience working with the disabled, and Winter Came Early: Reflections on outliving my son“, about his beloved son Jon who ended his life in 2019 at the age of 27. He is the cofounder of Friends in Time (a nonprofit he founded with a friend who has ALS), and past board president of New Mexico Parkinson’s Coalition and Pathways Academy (a school for kids with autism and other learning issues). A regular contributor to various journals, Gray also writes a weekly blog on www.michaelgrayauthor.com.

Healing the Wounded Mind

Healing the Wounded Mind

Images | Gerd Altmann

The Future Now

We are on the cusp of a different world coming into being, and at its centre shall be the human heart and soul. There can be no genuine, lasting future if it is based solely on the exterior life—it must be driven by the values that come from the interior of the human being.

Our technologies have given us the means to communicate across the globe in every moment—yet they have not taught us how to cultivate intuitive thought. Our smart machines and artificial intelligences may continue to advance the means of communication, yet the responsibility is on us to supply the meaningful conversation. As philosopher-mystic Paul Brunton said,

“A change in thinking is the first way to ensure a change in the world’s condition. In changing himself, man [sic] takes the first step to changing his environment and in changing his environment he takes the second step towards changing himself. For the first step of self-change must be a mental, not a physical one.”[1]

If our attention is focused externally upon the objects of our experience rather than the consciousness of the experience, then our minds will exist in separation. So, too, will our place in the world feel one of separation.

The ‘future now’ requires of us that we recognize unity over division. Much of what we witness in the world today are these divisions, dualisms, and conflicts that keep the game of life in play. The dualisms and the distinctions—such as good and bad, and ‘I’m right but you are wrong’—are not essentials (although we often mistake them to be). The world is full of angels and devils (to use a worn analogy), where the angels are winning but have not yet won, and the devils are losing but have not yet lost. And so, the constant interplay keeps the game active and dynamic, and not static. Yet we often lose ourselves by becoming attached only to these secondary aspects and missing the unity that underlies all. When we adhere to definitions or labels, then we have already created a boundary. By labelling, we are creating categories and comparisons that, by their nature, limit us. True things are beyond such defining categorizations. Truth is not a relative position—only human truths are. No wonder so many sages and prophets spoke in parables and riddles. It is the most useful mechanism to deliver the unspeakable.

If we ascribe to a life lived as islands of separation, then inevitably we learn (or are conditioned) to place our trust externally upon a range of institutions; these may range from religious, work/career, social, educational, etc. And if these institutions fail us, then we naturally feel vulnerable, or even betrayed. Yet the truth of the matter is that we betrayed ourselves in the first place by outsourcing our trust. If we live a life relying upon external systems, then we must be prepared to feel distraught should those external systems break down. In times of great transition, such as now, these social institutions are themselves very fragile.

It is important that we recognize that much of our everyday life is negotiated between these ‘belongings’ and similar attachments that we pull and wrap around us, like a protective overcoat. At the same time, we need to recognize that our world of ‘belongings’ is changing. We have ‘belonged’ to our nations, our cultures, our religions and belief systems, to our politics, to our teams, our communities, etc. We were largely brought up within our collective belongings that gave us some semblance of a fixed environment. And now, many of these collective belongings are breaking apart; they are unravelling. In the face of all these challenges, we may ask ourselves: what can I do about this? To this question, the remarkable Carl Gustav Jung answered:

“To the constantly reiterated question ‘What can I do?’ I know no other answer except ‘Become what you have always been,’ namely, the wholeness which we have lost in the midst of our civilized, conscious existence, a wholeness which we always were without knowing it.”[2]

As long as the majority of people expect all problems to be solved outside of themselves, then our societies will continue to be dominated by unruly forces. Our human freedom from these forces depends upon people willing to assume the responsibility of consciousness, and to project this inner reality outward upon an external environment. Whatever the question, being human is the answer.

Soulful Freedom

In a world full of work, family, and personal commitments, it may seem difficult—and, for some, almost impossible—to focus upon the notion of one’s soul and self-development. Yet it is very necessary that we do so. This focus upon our internal development has also been termed as self-actualization. This is a fairly academic term; maybe a more appropriate term would be self-activation, for the truth is that we do need to get activated.

Based upon the theories of humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow, a self-actualized person is supposed to embody the following characteristics: they embrace the unknown and the ambiguous; they accept themselves, with all their flaws; they enjoy the journey, and not just the destination; they may be unconventional, but they do not seek to shock; they are motivated by growth rather than the satisfaction of needs; they feel themselves to have purpose; they are not troubled by the small things; they express gratitude; they share deep relationships with a few, yet feel connected with the whole human race; they are humble; they resist conditioning; and they recognize that they are not perfect.

The inner essence of the individual—our soul—is timeless. It understands stability and aims for harmony and cohesion. In truth, we long deeply for harmony, not conflict. Within the material world of shadows and mass psychosis, we need to exercise a great deal of patience, tolerance, and empathy whilst preserving the integrity of our soul. The ageless, perennial striving for mystery, majesty, creativity, and conscious development is anathema to those who wish to preserve the power of the abusive mental pathogen that twists and manipulates our human lives. The survival tiger within us has, for far too long, lived within an environment of separation, struggle, suppression, and segregation. This mode of living has fed our egos until we have come to the point of priding ourselves only on our own ‘tiger instincts’ and our ability to get to the top. Yet contact with the transcendental elements within life embody compassionate relations, empathy, and connectedness.

The ancient, perennial wisdom traditions recognized that our morality depends upon our state of consciousness. An unconscious person, or a partially conscious person, is not able to express the same level of morality as a more conscious, realized person. What this tells us is that the moral state of our societies depends upon our internal states. Each one of us is a carrier and transmitter of consciousness. This factor has been abused by the Wounded Mind to spread its contagion. Thus, an unconscious humanity is less capable of making good choices, and is more susceptible to social conditioning, propaganda, and manipulations of the mass-mind.

Soul growth, or inner knowledge, is not an accidental emergence, but something that first must originate, consciously, within each one of us. It’s not a question of ‘should’ we work to become more conscious as individuals, but rather that we must. When it dawns on people that the transformation of the self is more than an interesting idea—that it is an actual inherent potential and living reality—then real change can begin. Perhaps our greatest ignorance is our unawareness of the potential of our soulful freedom and its power to create outward change. We have lived for a long time in ignorance; worst of all, in ignorance of ourselves. There is more to life than just living in the survival mode of the Wounded Mind. It is time to leave the tiger behind us.

Adapted from Healing the Wounded Mind, by Kingsley L. Dennis / Clearview Books / 2019. Reprinted with permission of publisher.

Adapted from Healing the Wounded Mind, by Kingsley L. Dennis / Clearview Books / 2019. Reprinted with permission of publisher.

About Kingsley L. Dennis

Kingsley L. Dennis, PhD, is a sociologist, researcher, and writer. He previously worked in the Sociology Department at Lancaster University, UK. He is the author of several critically acclaimed books.

Notes

1. Paul Brunton, The Spiritual Crisis of Man, 1974 ed. (London: Rider & Company, 1952), 64.

2. Stephan A. Hoeller, The Gnostic Jung and the Seven Sermons to the Dead (Wheaton, IL: Quest Books, 2014), 215.

A Story Still Unfolding

A Story Still Unfolding

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” ― Søren Kierkegaard

The creek behind my house seldom freezes. Her flowing waters can be seen from my back porch this time of year through the naked trees. Ridley Creek’s source is about 15 miles upstream from here and she pours out into the tidal Delaware River about 15 miles southeast. Yet, her journey is much longer than mere miles, for she has been a cloud, the tears of a child, and a rainstorm in some of her previous lives and her future is a story still unfolding.

The creek behind my house seldom freezes. Her flowing waters can be seen from my back porch this time of year through the naked trees. Ridley Creek’s source is about 15 miles upstream from here and she pours out into the tidal Delaware River about 15 miles southeast. Yet, her journey is much longer than mere miles, for she has been a cloud, the tears of a child, and a rainstorm in some of her previous lives and her future is a story still unfolding.

Likewise, here we are at a singular moment. If we could freeze the river of Time, we might skate ahead and learn our fate. We can’t. However, we do know that in this moment the future and past are also present. We hold the past and future within us. Upstream…downstream. Therefore, we can’t explore the theme of our winter edition, Possible Futures, without looking deeply at the past.

I asked author Jeremy Lent, who has spent a lot of time studying human civilizations, where we lost our way as a species that shares. His insights bear reflection if we want to understand where our present trajectory may take us. Read our conversation in The Next Civilization.

We also look back to look forward at the works of Thomas Berry and Rudolf Steiner. The Rights of Nature movement, that Berry so strongly endorsed, is informing new perspectives about our living Earth, and Steiner’s ‘biodynamic agriculture’, among other economic insights, are amazingly fresh today with regenerative culture on the rise. Rob Hopkins, a cofounder of the global Transition Town movement, looks back at how his community transformed Totnes in the UK, to become a model for current and future transitioners worldwide. The fundamental ingredient is imagination, he says, as we move from What Is to What If.

Personal tragedy also shapes our perspective on the future and there are important, albeit painful, insights to be gained when sorrow strikes close to home. What does it mean when all possibility of ‘a future’ seemingly ends? Kosmos contributor Michael Gray courageously expresses the grief of losing his son to suicide last spring. And our dear poet-friend, Lee McCormack, receives a terminal diagnosis with inspiring grace and strength. How do we live into such experiences of finality? The Unexpected Journey of Caring, by Donna Thomson and Zachary White, offers some transformational guidance.

There is much more to share—wonderful galleries of art by Aboriginal artists and by Flemish-Congolese artist/activist Kito Mbiango, and music from prisons, Pros and Cons, a social justice program founded by Hugh Christopher Brown. Kosmos music editor Kari Auerbach has also assembled a sacred season gift for all of us—a collection of inspiring recordings from her two years with Kosmos. Play it here, while you enjoy this edition.

A strong current of hope runs through thoughtful essays by our readers, and a spotlight on Global Social Witnessing, our capacity to mindfully attend to global events with an embodied awareness. Or as Otto Scharmer says, “collapsing the boundary between me and the other more and more. And really putting myself into the service and support of the evolution of another and the evolution of the collective.”

A strong current of hope runs through thoughtful essays by our readers, and a spotlight on Global Social Witnessing, our capacity to mindfully attend to global events with an embodied awareness. Or as Otto Scharmer says, “collapsing the boundary between me and the other more and more. And really putting myself into the service and support of the evolution of another and the evolution of the collective.”