Social Breakdown and Initiation

Charles Eisenstein’s New and Ancient Story is a series of conversations, interviews, and talks dedicated to the transformation of self and society. Explorations include technology, spirituality, agriculture, healing, economics, politics, ecology, relationships, education—areas undergoing transition today as our old story nears collapse. Visit CharlesEisenstein.net.

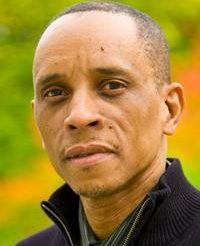

Orland Bishop is the founder of ShadeTree Multicultural Foundation and works in Los Angeles doing peace work with gangs, social healing, youth initiation, as well as research on esoteric and indigenous cosmologies.

Charles:Orland, I flatter myself to see you as a really deep ally in a cause that is so mysterious that I really can’t even say what it is, but there’s a sense of deep alliance. Thank you so much for making the time.

Orland: Absolutely. It’s a real pleasure to be together again, thank you. You’ve been a great source of inspiration for many years, so glad we could spend this time.

Charles: (In our last conversation) …You were talking about Martin Luther King and civil rights. I had this idea that we are in some kind of transition from civil rights to social agreements because the whole concept of rights kind of takes for granted the separate individual in relation to a sovereign state. As we transition, as a civilization, to a more fluid relational self, perhaps that old rubric of individual rights in reference to the state is evolving as well, and I’m curious what you might have to say about that.

Listen to the Conversation

Part 1

Part 2

Orland: I appreciate the framing. I think there is a transition from where someone is empowered to believe more in themselves, to believing in the other just as deeply. A right is not just for me. It’s an acknowledgement that the framework that gives me access to my own potential is the same framework that gives access to someone else’s potential. So this is the idea of civility. Civility is the framework that allows people to communicate in ways that allow the collective potential to be realized and achieved. This process of creating the direction in which an individual joins the collective intention is what a civilization is. It’s hard. The first phase is not rights whereby I think of my own needs, but R-I-T-E. This is where it emerged from, the rite into a relationship with the hierarchies within the deeper conception of society. And society used to be an initiated group, not a group of people trying to do their own thing, but a group that’s trying to realize the collective intention. But that required an R-I-T-E, rite of passage, or rite of leadership into that decision process. When that doesn’t happen, when people just get their rights as they know them to be, the demand is for more, more power.

Charles: So the R-I-G-H-T is kind of a substitute for the sacred R-I-T-E and becomes necessary, maybe only necessary, in the absence of sacred rites of initiation into society or into civility. That’s a really provocative idea because it then leads to the question: In this time of disintegration of all of the social structures that allowed us to be initiated into something, how do we reconstruct a society that is civil in the sense that you’re talking about, in which we have something to be initiated into?

Orland: So this is the framework. The civil rights movement had behind it a spiritual conception that they were not asking for something alone for themselves. They were also bringing something that was missing in the culture. They were bringing civility to the culture which meant: can people acknowledge that power is not withholding, it’s actually sharing? If you want to develop power, you develop it in a collective sense, whereby the highest reaches of human aspiration is in service to something that is sacred. So if I don’t make the other person’s needs sacred, I’m actually debilitating society. I’m creating frameworks of limitations, because the power that I see will remain political, but not become really social. So the higher power in the culture is social. It’s not political or even economic.

So self-interest is actually a betrayal of the self at another level. When I take so much that my own potential gets underdeveloped. Greed is an underdevelopment of the human potential. And in an intellectual society, in which the schooling of the intellect is for achievements for the self, it’s a critical danger when we do not have group aims as part of the exercise of education. Civics must be part of that education. We must realize how to contribute to a greater societal good, in indigenous forms, and indigenous in this sense just means when people who are situated in the particular place realize that the ecology of that place gives each person a unique feeling for what they can contribute to the emergence of what the place could inspire the group to share. An economy doesn’t have to be repressive. There’s enough imagination in this framework for a deeper collaboration and abundance is possible in everything that a group of people can share.

Charles: Today we live in a time where, for many reasons, we are deaf to promptings of land, of place that could coordinate us into a common endeavor and a common aim and earth agreements that situate each one of us in our gifts, in contribution to that aim. We don’t have ways to ‘hear’ the land, partly just because of an ideology that holds nature as a bunch of random forces and also because of a commodity economy that sources everything from distant places and obliterates the uniqueness of things and keeps us indoors in front of screens and so forth. What is the next evolutionary step to cohere again on a level that’s bigger than just the level of a place, but to cohere as a people?

Orland: Yes, you describe very carefully this gap between object and subject. We have, in our societies, objectives. We want to achieve certain goals, certain distinctions in the culture, and then we limit the capacities that are necessary for that development by isolating ourselves from the good that our aims must also inspire. Human being must ‘do good.’ We must embrace beauty. We must embrace truth. These are intrinsic qualities for a kind of moral memory, that we’re not just pursuing achievements in the outer sense. We’re also developing inner capacities to realize, ‘when I achieve something it’s actually good for the world.’ So what I’m pointing to here, is that in the objective reach in the human will, we have an inner subjective awareness that comes with it. Is this thing that I’m acting on creative enough to transform my life? If it’s only objective is the degree to which I get it done but I don’t have an inner experience of goodness for it, then I’ve actually not done anything. So the society becomes mechanistic in the goals it sets because it could just be done without consciousness.

Charles: I’m imagining, though, that you’re not advising people to disengage from action in the world to heal racial and class inequities, and just to come and work on self-consciousness instead. I imagine that’s probably not what you’re saying.

Orland: So it’s not either/or anymore. It’s both simultaneously, what I call objective subjectivity. I’m working on myself as I’m working on the world at the same time. There’s no other way to do it and this process requires a careful observation that, as one of the poets put it, ‘I’m not a workman in the world, I’m a prophetic being. I can see into things and I can see into myself.’ So why not do both?

Charles: There’s no alternative. When you say okay, yes, I need to work on myself but how do I do that, I think it’s through the things that become visible when one is in relationship to something in the world.

Orland: Right. The world has become myself. There’s no self because I am holding the world in it. My world view is the world, so however I see things is really me and the world at the same time. My perception is no longer separate from the world. It includes and holds the world in it. My cognition holds the world in it, so every time i act, I’m actually acting on the world and myself at the same time. It used to be that I could only see one and then look at the other, but consciousness has evolved to be able to hold both simultaneously.

I think we become more real, as well, as we get older in the sense that more of my spiritual capacities become accessible to me in this mid-age range. It’s called a second adolescence, where the chemistry of life gets back into the deeper spiritual body we call the astral body. This is the part of the self that, in a sense, holds the future sense of me. If I want to stay in my old habits, I’m actually going to create illness for myself by a certain age if I don’t release my creative. But this is also true for the whole culture. If we don’t embrace our future potential, the social aims, the cultural aims, the political aims and such will break down because this is actually a representation of the inner life of the human being.

Charles: It looks like it’s happening right now, this breakdown in our culture.

Orland: Right, and because we live in a technological age, we may want to substitute everything with technology, but the need would never be substituted. The need that we have is fundamental for the R-I-T-E part of our lives, the rite of passage part of our lives, the initiation part of our lives has to continue to be developed. There’s no substitute for that because it is actually an intrinsic feeling. No one can give us that unless we are working on something that is actually truthful in our will.

Charles: I’m just digesting that and thinking about the dramatic increase in suicides among middle-aged people, especially men, and I wonder if there’s a connection—when on the soul level you know that something is supposed to happen, initiation is supposed to happen, a new phase of life is supposed to happen, an orientation toward, on a deeper level, an orientation toward what you’re born to serve. And then it doesn’t happen. The initiation doesn’t happen and one feels confined in this obsolete life, this shell, that cannot accommodate who I really want to be.

Orland: The esoteric probably will become more realized in our society as we go along. Esoteric means ‘what’s hidden’. What’s hidden often in the motive of life is to have the knowledge of what is actually generating the questions that I’m having. If a person can’t answer the questions they’re having, with the knowledge society provides, they can only go one place: into themselves. Initiation is often a brush with death.

The human being is always dying. This is the esoteric part of the human life. We’re always dying, but we also are always living and the question is: what experience will pull us to one or the other? The human being is always in a balance between life and death. Some practices tell us to pay attention to one or the other and learn which one tells us the deeper truth. Initiation questions really must take in both. The deeper philosophy of life takes in both. The deeper religions of life takes in both. The contemplation of life and death, it’s not one or the other.

Charles:I’m thinking now, on collective level, that we are probably in a phase where we are drawn to the contemplation of death and to the reality of the death that is present in life because of climate change, perhaps, because of these crises that are putting in front of our face that our entire civilization is mortal.

I think we are having a collective initiation that started with the bomb, which was the first time that it became inescapably obvious that war is not the answer. It became no longer a viable option to defeat the enemy through total war. For the first time in human history, that was no longer an option. Instead, we had ‘mutually assured destruction’ and that gave us a quickening in the evolution toward what I call the story of interbeing—that what we do to the other, we do to ourselves in some form. Now, we have climate change. I think that the dominant narrative of climate change is really problematic, but still its effect on us is to drive home the point that what we do to nature, what we do to other beings, not just human beings but what we do to any being also will affect ourselves. Maybe you have a further comment about that?

Orland: I appreciate you framing it further. We’ve been in a cult of death for a long time—our modern civilization, from colonialism, in which cultures have died. We’ve actually extinguished a lot of significant cultures from the world in the last five- to six-hundred years. So the atomic age is actually not the first of really seeing massive loss of potential. We’ve also eliminated a lot of species from the world.

What has been evolving in those 500 years in modernity is this objective subjectivity, that if I destroy the world, I destroy myself. That’s hidden in the initiation we can call ‘the atomic age,’ but it’s still a rite of passage of humanity, from the ages where electricity and magnetism and fire would only limit destruction to a certain point, now it’s global. This level of destruction has put our contemplation of death at a higher level and we don’t want that. So what do we do? We started to learn how to negotiate the atomic energy age.

Charles: Yes.

Orland: But this is, again, when we put ourselves at risk, we put ourselves in the opportunity of development at the same time.

Charles: Yeah. I’m just wondering if there’s even any other way. I think about the extinction of cultures, languages, stories, not to mention species, and I wonder: is there some gods’-eye-view of the whole thing from which I can understand that actually these extinctions were a necessary sacrifice to complete an evolutionary journey that we are collectively on? Is there another way to understand these extinctions in some other way besides that they were just horrific tragedies? I’m not saying as a substitute for feeling them as a horrific tragedy, but I’m saying like another lens through which to understand them?

Orland: This brings us back to the esoteric question. Some of the areas of research that we are engaged with is to understand what is on the other side of death. What happens in the release of the life forces from the form we call our body, of any body? What happens with the energy once we leave?

Ultimately, most of us will have to become esotericists if we are to make sense of the losses that we have already endured in our culture. Why? Because the energy is still trying to communicate with consciousness. So the bodies are gone, but the beings that inhabit those bodies are still active on different planes of reality, causing environmental changes because it’s still constituted within the framework of what we call reality.

Charles:So I collect stories and I hold circles sometimes where people share stories that involve death, involve communications with loved ones after they died in very dramatic ways. I think that these can be very useful to take in because they subvert the dominant conception of what a self is and ‘who I am’ and open us to other conceptions. I think that some of those people will then jump too quickly to kind of a simplified transmigration of souls from one lifetime to the next, to the next, to the next, which still kind of preserves a sense of a separate self.

These stories really make me curious and they inflame various skeptical parts of myself and wounded parts of myself, parts that maybe want to believe these experiences are authentic and I’m afraid to believe they’re authentic. I will become I wouldn’t say cynical or skeptical even, but it’s more I kind of hold it at a bit of an intellectual distance. I feel a call, though, toward a deeper understanding. Maybe all this is just a long-winded way to say, Orland, what happens after we die?

Orland:What happens to my thoughts when I forget something? Where does my knowing go when I forget something? Before we even get to the death part, when I forget something, it’s still available in some level of consciousness, and if I concentrate my attention I can recover what I forgot. We call it remembering. So remembering is the first process in the step to clarification of this higher practical development. if I choose to remember, my consciousness actually becomes much more complex than if I try to learn something because I will resist learning, but I can’t resist remembering. In early childhood, that’s who I was. I was trying to remember, not learn, and I was hoping that those who were older than me had remembered everything.

Back to perception. Our natural perception is to be open to mystery, but having learned that mysteries actually create strong paradoxes in consciousness—meaning no one can always explain what I’m perceiving—then I have to really advance my cognition. And we have a society that’s saying, ‘do not advance your cognition too far or you will be considered weird.’ You know, we ostracize people that advance themselves. Or, if we can utilize their knowledge we call them geniuses. If they play good music or they create good mathematics, we then make space for them.

Charles:We have these capacities that we, in some semiconscious or unconscious way limit in order to remain in coherency with the times in which we live, to ‘not be weird’, or it could also just be that the particular flavor of genius that would become available to us isn’t necessary or doesn’t even have a home right now. The genius has a purpose of service to what the next evolutionary step of that society is to be. It still feels, though, a bit tragic. Some people, they get to exercise their genius. They get to be a musician, a mathematician. They get to do it and others, sorry, your genius is not what’s needed right now so you just get to be a janitor. That can’t be right. There’s something else here.

Orland: This is the subtle thing about karma and destiny: it’s interwoven. So part of the karmic factor is that there will be some condition that limits my creativity that is beyond the society, but also hidden in the society. This is an agreement that a circumstance will limit my destiny and I have to figure out the rite—R-I-T-E—of passage through that. It’s not just that everyone will have everything they need. Even if you provide everything they need, they will still require something that makes consciousness a deeper effort.

Some people will even self-sabotage their own potential because that is just part of the make-up of what initiation is. The human being must be initiated, regardless of how much society provides the conditions necessary for achievement. It’s really not about achievement, it’s about transformation.

Charles: It seems like there’s two things that might require an initiatory rite. One of them would be to be initiated into society as you were saying, into a useful function that engages the gifts that you come with, and the other is the initiation into the activation of the gifts themselves. If you have one without the other, if you have the social initiation without the activation of the gift, then your utility is limited because you’re only operating from what is automatically available to you. If you have the initiation of your genius without initiation into society, you become kind of the lone genius or even the psychotic.

Orland:We’ve lost the context of the genius. The genius is guided by the muse and so there’s always a sense that the inspiration for the genius to become active is the fact that there are entities or intelligences that are the source of what the genius utilizes to express this unique capacity. Music is not just in the person’s capacity to play, it’s in the spheres, in the harmony of the spheres. It’s already there and it’s discovered and played.

Charles:Yeah, Mozart would just write it down.

Orland:Yes. Right, exactly. So these frequencies are distributed throughout the cosmos so to speak. It’s within the environment in nature and the deep superconscious of the collective. So part of it is that we’re always drawing from something through our perception.

Charles:That’s why initiation is necessary because it’s an attunement to something that’s already there.

Orland:Yes, and when the spirit self-separates from the physical body, there’s a recapitulation, a remembering, of the primary agreement of what the self brought to the world and a witnessing of: did I fulfill it, did I live into this intention? It’s not a moral thing of beliefs. It’s whether I truly made the effort to overcome self-interest and deposit into the world my will, leaving my signature with it that’s free from ‘me.’

Charles:It seems like a bit of a stringent standard that you’re setting up here. You know, when I ask, when I meet somebody and they have incredible potential and I ask well why aren’t they fulfilling that potential and then I hear, well they were abused as children, they went through all kinds of things, no wonder. You’re not saying at the moment of death that they’re going to evaluate that they have failed because, I think really, sometimes when I offer something to people who are deeply wounded like that, I say, “you know, if you accomplish nothing else but to heal 10% of that, then you’ve actually had a really good life.” How does that fit in?

Orland:Yeah, I would agree with that and that’s why I went back to remembering, because anyone who is in a crisis, what they’re trying to do is remember a time when they were not. They want to go back to a time before the abuse. They want to go back to a time before the trauma. The body tries to remember this earlier stage when it was not yet wounded or when it did not forget its higher purpose. We call it healing, and you just mentioned it again. This is the natural first process of the self. It wants to overcome the conditions that limit its conditions to be self-conscious. If it doesn’t happen in remembering, it will try to happen in sleep. If it doesn’t happen in sleep, the only other option it has to happen in society, in waking consciousness. Someone has to insist that there’s an opportunity to heal. Someone has to provide the context. This is society’s work. We should not leave people in their wound. This is why people explore all kinds of therapy because we know it’s possible for that breakthrough. If it doesn’t happen then, then it’s left for these other levels of the mystery which would include that.

Charles:I think that you’ve articulated the most important requisite of successful therapy of any kind, which is that the therapist whether it’s a person or a group has to know that the other person can heal and has to be able to hold that knowing strongly enough that they can hold the other person in that knowing until they can know it themselves. That’s almost the only thing necessary. I guess there are skills and things and learnings that are useful on top of that, but without that there’s nothing.

Orland:Because the highest level of the self-need is belonging. Even if I don’t accomplish anything significant, belonging is most important to the human being. No one wants to just be exiled in a wound by themselves.

Charles:It kind of comes full-circle, because the particular gifts and genius that are especially called for in our times and called forth by our times are precisely the ones that enable us to create conditions for this healing to happen for other people. Everybody’s gift is to serve the healing of somebody else.

Orland:I would definitely say yes to that. Something we share becomes more abundant, not only to me and to us in this time, but it becomes the substance for future times as well. It becomes the criteria for some other soul that is going to be born into the world to say, “this is the right time, this condition is set.” We set the conditions upon which the karma of other people’s lives gets identified.

Charles:Returning to the death moment here, is that okay?

Orland:Yes.

Charles:So there’s this kind of evaluation and then what happens?

Orland:Well, when one goes back into the deeper story, which there’s a memory in the astral body that has to be transformed. This life is a memory. It becomes a memory that has to be transformed to prepare free energy for the soul to possibly reincarnate, for possible futures. It has to dissolve this content and context of life itself. That is the work for those on the other side: dissolving who they had become and allowing the soul to return to a state of creative freedom, to be reincarnated again.

Charles:That doesn’t only happen with death. That happens in life transitions, too. It’s necessary to dissolve who you’ve become.

Orland:Right. So when we don’t complete all of that … that’s why I said in the living experience, we have the same functional capacities that we have in death. We just have to do it in a body, we have to do it within the framework of perception and cognition. The perception and cognition has to pass through the living organs of our individual existence. This is one part of initiation. If it doesn’t happen there, it has to happen on the other side of the body.

Charles: Right. If it happens on this side, then capacities become available.

Orland: Spiritual capacities become available here that we normally would only experience on the other side.

This is the stage in all consciousness development whereby we must contemplate. The will wants to aspire for something to do, but I can only aspire to the level of the contemplative will first, whereby I don’t have to feel the push, but the pull to wait for the inspiration, because the inspiration comes with a kind of initiation as well. The one thing that we don’t want to do is intellectualize it to the degree that I want to make an achievement of it and not a realization of it. When I realize it to be true, what is in me will naturally awake.

Charles: I’m so grateful, Orland. I hesitate often to reach out to you because I just know that you’re doing such important, beautiful work that I don’t want to take you away from it.

Orland: No, this is good to do. This is a source of inspiration for me too.

Charles: Great. Okay, well thank you so much and I’ll talk to you tomorrow.

Orland:Talk to you tomorrow. Take care.

Listen to the complete conversation here.

I’ve been listening to Part 2 of this conversation over and over. I even started the laborious process of transcribing it. I hoped someone had already transcribed it. Then I finally looked at my Kosmos Summer Quarterly, 2018 and was delighted to find this transcript. You have the audio of both episodes (E26 & 27) but the transcript is of Part 1 (E26) only! Do you have a transcript of part 2 (E27)? If so I would LOVE to see it.

There was no confirmation that my comment was received. It just all disappeared leaving no trace. Please confirm receipt

Hello Ed,

Your comment has been received. We had a little problem with the website when you first entered your comment.

Thank you so much for your interest.

Hi Nancy. I’m a longtime subscriber and fan. Can you see if whoever transcribed Part 1 of the podcast with Charles Eisenstein and Orland Bishop also transcribed Part 2? I’m guessing that since you published the audio of both parts, you thought you had published the entire text. I would love to see the textual transcription of Part 2.

Sorry to report I only transcribed part 1! Glad you enjoyed the first half at least 🙂

This is a labour of love, thanks so much for transcribing the conversation Rhonda, wow! I’ve been hoping to get around to doing this for years, having listened to all three conversation parts over and over.

a pleasure 🙂