Reemergence of Animate World Experiences

(based on a short “workshop” given for Harvard Divinity School’s “Ecological Spiritualities” Conference, 2022)

To shift my own awareness toward a more-than-human perspective, I sometimes take a wooden flute outside and begin to play, offering simple music to pine and stone, offering gratitude to billions of ancestors – from elements born in supernovas, to bacteria and trees, insects and trilobytes, to lineages of human ancestors both known and unknown. Offering wild prayers for all the beings who come after us, as well as gratitude to all of the teachers, both human and wilder Ones, is a practice to help destabilize my everyday mind and perceptions. Sometimes it is as if I hear the world breathing in response to the melodies.

The everyday mind might intellectually understand that the world is saturated with intelligent presences, but experiencing the world’s animate and participatory nature is a different dimension of depth and heft, and likely engages the body, felt-senses, emotions, and imagination as well as the intellect.

In an alluring shift from a human-centered perspective, poet A.R. Ammons writes that “it is not so much to know the self / as to know it as it is known / by galaxy and cedar cone. . . .” Considering what “self” or identity the galaxy sees and knows is likely unsettling for many of us. Is the self that we regard as ours identical to how we are known by salmon and dragonflies? Does the land see me as I see myself? Would I change in significant ways if I knew what the cedar cone experienced as I pass by? Would I become more integral to what the geologian Thomas Berry calls the Earth community, which he regards as a communion of subjects rather than a collection of objects?

I am writing from lands once inhabited by the ancestral pueblo people – people whose potsherds and lithic scatter sometimes turn up in the nearby field – an ever-present reminder that civilizations don’t always endure. I’m near where the water that’s known as Deer Creek gathers, in the Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, in the Colorado River watershed.

I want to acknowledge that the world is amidst a tempest of climate disruption, social disarray, creature extinctions, ecosystem collapse and other mayhem, with too few leaders who have perceptual skills, sufficient imagination, or a strong enough compass to navigate the riptides of enormous change. Our accustomed styles of knowledge gathering and information-processing might not be adequate to the crises of our time. We who are steeped in the Western mind and Western worldview of progress and consumption in a dead universe may need to disrupt our everyday thinking, our strategic minds and psychic habits so that some other – and perhaps wilder – voices can find us. Perhaps in the small amount of time that we share, we’ll disrupt our everyday thinking a little, perhaps crack ajar, even slightly, what William Blake called the doors of perception.

When I gather with a group, it is typically in-person, outside, in a wildish place, among wilder Others. So to begin, let’s imagine we are sitting in circle somewhere, hearing the voices of birds and leaves, and the breathing of each other. If we were in-person, I’d invite each of us to begin with an acknowledgement of the wilder Ones with whom our lives are entangled. If we were gathering on-line, I’d invite you to use the “chat” for brief honoring of other-than-human beings with whom you have emotional connection. If it feels right to you, please name the other being, and also something that allures you about them. Just now, I want to praise a particular ponderosa pine, one I regard as a grandmother, whose lower limbs are so massive they are now bending to rest on the ground. She smells sweet, like vanilla, when I press my nose to her rough skin.

Let’s fill the world psyche with praise for the wilder ones with whom we feel connected, noticing what emotions or other response that honoring or praise evokes, if any. When I feel off-balance, or when my mind is running on an unfortunate hamster wheel of repetitive thoughts, sometimes I go out to the land in praise of each presence I encounter, specifically noticing the unique shape or expressions in my praise. Often, mostly, my awareness will jump the track from whatever I’ve been obsessed with to the wider vitality of the living Earth in which I am a grateful participant.

***

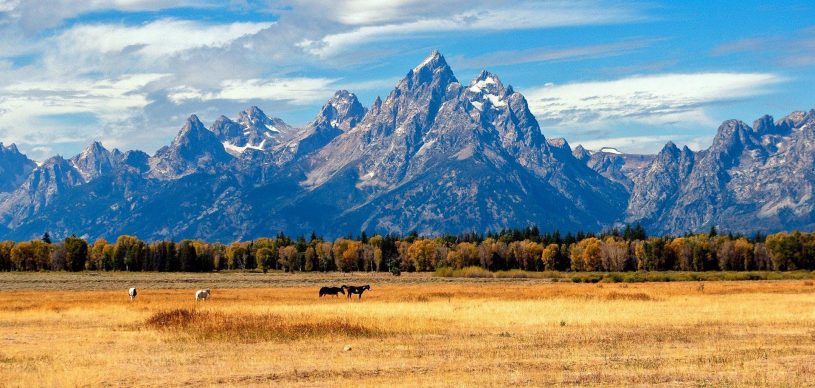

I lived for a long time at the edge of Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming, just south of Yellowstone. In these two parks, nearly all the wild species who were present at the time of the early incursions by white people are still present – or present again as with re-introduced wolves – midst regular encounters with bison, moose, elk, eagles, coyotes, Sandhill cranes, and so many more, I’d observe these wilder ones doing the things they do, fitting into the ecosystem in their particular and specific ways. I’d watch bison wallow on their backs, carving bowl-like depressions in the sage flats – bowls what would hold water when the rains came, indentations that made particular habitat for diverse plants. I’d tune my senses for the return of raptors when the Uinta ground squirrels emerged from hibernation in the spring. I’d observe the devoted dam building of beaver, slowing down rivers and streams, spreading out the water. And I’d wonder if human beings, like all of the wilder Others, had a species niche relative to the ecosystem we inhabit, which has become the entire Earth. I couldn’t imagine that human beings – unlike any of the Others – were without unique and specific purpose in relationship with the wider community of life.

What is unique about human beings? was the question that followed me. Other philosophers have supposed that our form of consciousness is unique among the animals, or our symbol-making ability. But I want to propose something else that may be unique to our species, and that is our ability to imagine what does not yet exist, and then to create it. As far as we know, no other species has this capacity, with which we have made violins, iPhones, Hubble telescope, nuclear weapons, space travel. I mean, we know that beavers, who must keep trimming their ever growing teeth, gnaw down trees to build dams – but they don’t seem to be building dams intended to light up Las Vegas. I want to propose that everything human beings have intentionally made, every modification to our “natural habitat”, was born first in imagination. For better and worse. The human imagination may be our greatest unacknowledged and underutilized innate capacity.

But in our era of ever-present media, our innate capacities for imagination may be suppressed by the constant bombardment of ready-made images from advertising, entertainment, news media, and political points of view. We are living amidst the greatest colonization of imagination ever known. In her poem “Rant,” Diane di Prima recognizes the catastrophic consequences of a battle for control of the human imagination: “the war that matters is the war against the imagination / all other wars are subsumed in it. / the ultimate famine is the starvation / of the imagination.”

Our human capacities for imagination can still be cultivated, though, even now, when imaginative acts may be essential for the well-being of the Earth community.

For today, I want to connect the human capacity for imagination with the capacity for perception of an animate world. I want to propose the possibility that even those of us who have been deeply-rooted in the contemporary Western worldview can become more receptive and responsive to Earth’s longings, wild dreams, and intelligence.

All of our ancestors, presumably, lived in a world brimming with participants, a world of companions, where birds might be regarded as messengers, where stone could be imbued with indwelling spirits, where snakes sometimes spoke or offered guidance. All of our ancestors, presumably, inhabited an animate world – some of our ancestors might still engage with a world full of intelligent Others, as in this excerpt of a poem by David Wagoner:

The Silence of the Stars

When Laurens van der Post one night

In the Kalahari Desert told the Bushmen

He couldn’t hear the stars

Singing, they didn’t believe him. They looked at him,

half-smiling. They examined his face

To see whether he was joking

Or deceiving them. Then two of those small men

Who plant nothing, who have almost

Nothing to hunt, who live

On almost nothing, and with no one

But themselves, led him away

From the crackling thorn-scrub fire

And stood with him under the night sky

And listened. One of them whispered,

Do you not hear them now?

And van der Post listened, not wanting

To disbelieve, but had to answer,

No. They walked him slowly

Like a sick man to the small dim

Circle of firelight and told him

They were terribly sorry,

And he felt even sorrier

For himself and blamed his ancestors

For their strange loss of hearing,

Which was his loss now.

The “strange loss of hearing” and other diminished perceptions that Western people have seemingly inherited from our ancestors can evoke deep grief when we recognize the enormity of the loss. Yet, this older perception might be revivifying beyond the margins of the dominant Western culture in compelling campaigns for rights of nature, or for personhood of rivers. “Rights” and “personhood” imply intelligence, subjectivity, and purpose – expressions of animacy. And we see this older perception alive – still – in children’s stories, in myths, and with some poets, essayists, and novelists, where other-than–human beings are allowed agency, intelligence, and their own longings.

Many contemporary people understand that other-than-human beings are intelligent and saturated in subjectivity, but the understanding might be more intellectual than experienced, because the dead universe worldview – with which most Westerners are deeply, though perhaps unconsciously, rooted – shapes perception. Those who seldom regard the Others as alive and intelligent may reflexively exclude from our embodied awareness any hint that suggests otherwise – even if we long for wildly intimate, reciprocal encounters and interactions.

For those unlearning the Western worldview, awakening perception of the musky, multivalent, psychically active, slow-breathing world can be a practice.

One way to re-animate perception is through our manner of engaging with, or writing and speaking about, non-human Others – including those generally not considered as organic or living, such as rocks, poems, or dreams. In his poem, “When I Met My Muse,” William Stafford creates a world where not only is the Muse engaging; it’s a world where sunlight, eyeglasses, ceiling and nails have agency:

I glanced at her and took my glasses

off—they were still singing. They buzzed

like a locust on the coffee table and then

ceased. Her voice belled forth, and the

sunlight bent. I felt the ceiling arch, and

knew that nails up there took a new grip

on whatever they touched. “I am your own

way of looking at things,” she said. “When

you allow me to live with you, every

glance at the world around you will be

a sort of salvation.” And I took her hand.

The poet not only personifies and personalizes “the Muse,” he also animates what are commonly regarded as non-living “objects.” His “own way of looking at things” includes the perception of non-human presences as active and experiencing. We might wonder how much his practice of imaginatively animate writing nudged open the doors of his perception. If perception shaped his poetry, his poetic language and images also stirred his perception. The two are twinned.

Poets naturally reflect on the power of words, but to give words, or books, life is an even deeper sensing. In “Hunting the Phoenix,” poet Denise Levertov leafs “through discolored manuscripts, / [to] make sure no words / lie thirsting, bleeding, / waiting for rescue.” In “August Daybreak,” she hears “the books in all the rooms / breathing calmly.” To write in such a way—to consider that words may lie bleeding, that books may breathe—almost surely affects the consciousness of both writer and sensitive reader, who may then hold language with greater care. At the least, such phrasing ignites the imagination. Consider the subjectivity of things without recognizable life. What of this keyboard, for example? Are the elements of plastic gasping under the press of my fingers, under the burden of my thoughts, the words I spell and erase? Are the rocks and feathers assembled on the bookshelves curious why I—like them—sit so long in one place, collecting dust? Do they wonder where I go when I leave the desk; do they dream of such freedom? Do these other-than-human presences have their own mode of curiosity and wonder, untranslatable to the human imagination? Or do these mute questions arise in the field between us and press themselves into the hands typing these words?

Dear reader, what arises in your imagination if you contemplate the possibility that the ordinary “objects” accompanying our days might have life and longings of their own? That the walls of the house were once part of a living forest; that the water through the tap has a wild origin? If our everyday awareness included felt-recognition of the noble longings of rivers, meadows, or corn, might we question, or even re-envision, our human ventures?

In my work as a guide toward the intertwined mysteries of nature and psyche, I’ve witnessed hundreds, maybe thousands, of people break free from the dead universe worldview and toward participatory intimacy with an animate world – encounters that usually involve some alteration of ordinary psychic habits combined with intentional acts of imagination.

Disrupting everyday perception can involve drumming, chant, praise, wild prayer, dance, guided imagery, vision fast, sacred medicines, extended wandering, ceremony, or other practices that destabilize psychic routines and allow us to sense what we might ordinarily exclude from awareness. For example, the modern mind is often so filled with stimuli and repetitive thoughts that even a robust chorus of birds is unheard until something disturbs and quiets the mental chatter.

Another practice that can alter ordinary consciousness is intentionally approaching the world as if all of the Others are as filled with longing, intelligence, and purpose as we regard ourselves. For adults in the Western world, this might involve effortful acts of imagination. But nearly all of us once knew the world as magical, filled with beings with whom we could play, engage in conversation, or regard as friends. Adults might call this magical world “pretend” – a word that curiously shares roots with “intend.”

If we intend to participate in the world as if every presence is alive and intelligent and aware, perhaps we catch ourselves a thousand times forgetting. Yet when we remember long enough, or often enough, we might crack the doors of perception – doors that may be shut by customary psychic habits – and enter that breathing world, where everything speaks, where every presence longs to be seen and known.

Participating as if all is intelligent and alive might involve speaking directly to or with the Others (rather than about them as if they are insentient and unfeeling). Participation might involve gestures of reciprocity like caressing bark or leaves, singing to monsoon clouds, or spontaneous acts such as ceremonially honoring the death of a sparrow who has broken her neck against the window glass. All of these are acts that help toggle us out of everyday, habitual perceptions. Then, if one is fortunate, a person might notice a subtle sense that the forest has a mind of its own, full of vitality and vibrant interdependence. Another person might hear the grief cries of the sea. Another might experience an electrifying, felt-sense of being witnessed – or called! – by a particular pine or stone.

Engaging directly, intimately, and imaginatively with other-than-human presences can enliven human awareness, which increases the likelihood of mutually beneficial relationships with all of life. In this fragile time of species extinctions, habitat loss, and climate disruption, becoming more sensitive to the longing-pains and voices of the wilder ones may be essential service.

There are uncountable ways to awaken perception of an animate Earth. Imagination is one of the wildest portals.

I listened to these short clips with my hand on my heart and tears in my eyes. Such deep resonance with your perspective, Geneen, of the active, wild intelligence of stones, water, plants and your participatory kindness with all that calls you. I know this sweet bondage intimately. The past thirty years have been spent exploring this realm of erotic kinship with nature as it took me far off the beaten path. Thank you for your gentle authority expressed through your voice, the resonance with poets, and the echoes of all the wild beings so present as you speak and write. A deep bow of resonance and respect.