Breaking Out of the Domination Trance

Remarks at the 2018 Safe Ireland Summit | Dublin, Ireland

I have been asked to tell you about the findings from my research identifying the core components of a safer, more equitable, and caring world—especially one where women and children are finally safe—a goal that is very close to my heart. In doing so, I will place violence against women and children in its larger social and historical context, and, most importantly, explore with you how to bring about fundamental change—not only in the prevailing worldview, but in our lives and our world.

So, I am going to share a great deal of information with you. But first, I want to tell you a little about myself, because my work, and the passion I have for it, are deeply rooted in my early life as a child refugee with my parents from Vienna after the Nazis took over my native Austria.

Questions from my Childhood

We only escaped from the Holocaust by a hair’s breadth. Shortly after that takeover, on Krystal night—so-called because of all the glass shattered in Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues—that night of the first official terrorism against Jews, a gang of Austrian and German Nazis broke into our home, and I watched in horror as they dragged my father away.

That night I saw cruelty and violence, but I also saw something else that profoundly impacted me, what I call spiritual courage. My mother displayed that spiritual courage, the courage to stand up against injustice out of love. She recognized one of the Nazis as an Austrian who had been an errand boy for the family business and confronted him angrily, asking, “How could you do this to a man who has been so kind to you?” Now, she could have been killed; many Jews were killed that night. But by a miracle, she wasn’t. And by another miracle, she obtained my father’s release that night—of course, money passed hands. A short time later, in the middle of the night only with what we could carry, my parents and I left Vienna.

Because they had been able to purchase exit visas and also entry permits to Cuba—one of only two nations that let in Jews fleeing the Nazis at that time—I grew up in the industrial slums of Habana, because the Nazis ‘confiscated’ (official word for armed robbery) everything my parents owned. And there, I experienced and observed dire poverty until my parents were able to get back on their feet again.

All these experiences—and yes, they were traumatic—led me to questions, questions many of you have probably asked at some point in your lives, like, “Why—when we humans have such an enormous capacity for consciousness, caring, and creativity—has there been so much insensitivity, cruelty, and destructiveness? Is it inevitable, or are there alternatives? And if so, what are these?”

These were the questions that many years later animated my research, writing, and activism.

A Second Turning Point

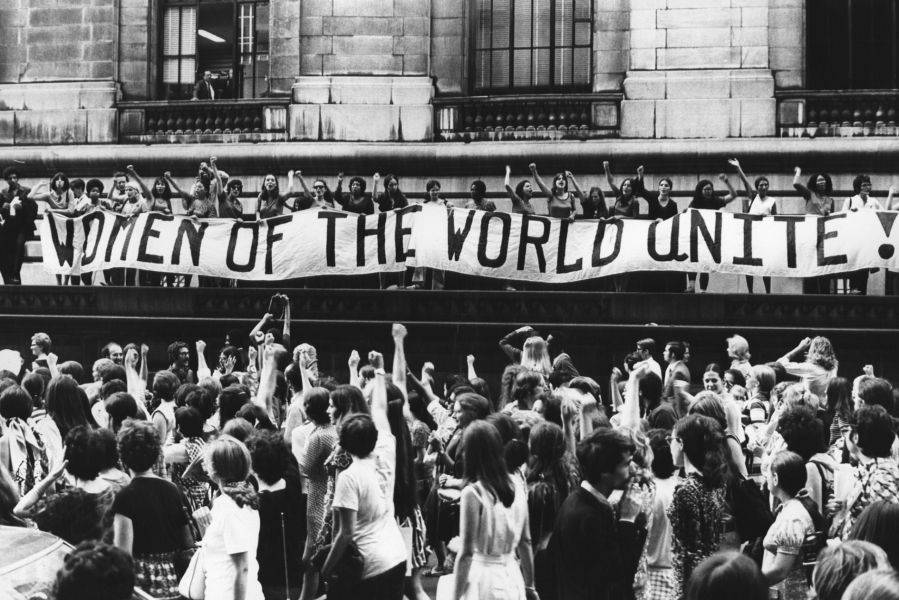

But before then, there was for me another pivotal experience that was in the late 1960s, when I suddenly woke up—along with thousands of other women in the West—to realize that as much as having been born Jewish almost cost me my life, having been born female also profoundly impacted my life, my life options, and even how I saw myself.

So, I threw myself into the then just emerging women’s liberation movement, the second wave of feminism, which, along with the backlash against equality for women, became trivialized as “women’s lib.” Even to this day, many people who consider themselves progressive regard traditions of violence and abuse of women as “just women’s issues”—a truly peculiar situation since women are half of humanity, and, in fact, women and children together constitute the vast majority of humanity.

Now the good news is that a substantial number of us are beginning to wake up from what I have called the domination trance, a trance perpetuated by all our institutions, our systems of belief, both our popular and scientific narratives, and even our language, so we are just beginning to see something that, once articulated, may seem obvious: that how a society constructs the roles and relations of the two basic forms of our species—male and female—as well as how it constructs early childhood relations, are actually fundamental social issues that directly impact whether all our social institutions—from the family, education, and religion to politics and economics—are equitable or inequitable, authoritarian or democratic, violent or nonviolent.

A New Perspective

This was a central finding from my multidisciplinary, cross-cultural research, which differs from conventional studies. Often aptly called the study of man, it draws from a database that includes the whole of humanity, both its male and female halves. It also differs from most sociological studies, which pay scant attention to family and other intimate relations. This database includes the whole of our lives, not only the so-called public sphere of politics, economics, and religion but where we all live—our family and other intimate relations. And rather than the siloed approach of conventional historical studies, it takes into account the whole of our history, including the long span of thousands of years of prehistory.

If we only look at part of a picture, of course, we cannot see all its parts, much less how these parts relate to one another. So, looking at human societies across time and space using this larger database makes it possible to see patterns, configurations that, yes, answered the questions of my childhood.

You can not see these configurations by looking at society through the lenses of our conventional social categories: right vs. left, religious vs. secular, East vs. West, North vs. South, capitalist vs. socialist, technologically developed or undeveloped, and so on. First of all, each of these old categories only look at a particular aspect of a society, like location, economics, or ideology, but also—and this fundamental—none of them tell us how a society structures our foundational gender and parent-child relations, even though we know from both psychology and neuroscience that the nature of these relations—which children experience and observe in their early formative years—impacts nothing less than how our brains develop, and hence how we think, feel, and act.

Moreover, if you think about it, societies in all these familiar categories have been oppressive and violent, as I will shortly illustrate.

It’s only by leaving these old categories behind that we see that cross-culturally and historically there are two underlying social configurations: the Domination System and the Partnership System.

And once we understand these two social configurations, we can answer the critical question of what kind of society we need to support our enormous human capacities for consciousness, caring, and creativity, rather than—because we obviously also have these—our capacities for insensitivity, violence, and destructiveness.

Domination Systems and Partnership Systems

No society is a pure domination or partnership system; it’s a partnership-domination continuum. But I want to briefly give you some examples of contemporary societies that are close to the domination end of the social scale.

These are very different societies if we only look at them through the lenses of conventional social categories: Hitler’s Nazi Germany, a rightist Western secular society; Kim Jong-un’s North Korea, a leftist Eastern secular society; the Taliban of Afghanistan, an Eastern religious society; the would-be theocratic regimes of Western religious fundamentalists.

Despite all their differences, these societies share the core domination configuration:

- They consist of hierarchies of domination, not only in the state, but also in the family, and all institutions in between.

- They support a gendered system of values. They rank male over female, with rigid gender stereotypes of Femininity and Masculinity, and, with this, the devaluation of anything culturally considered “soft” or feminine, such as caring, caregiving, and nonviolence, which are considered totally inappropriate for “real men,” just for “sissies” or weak sisters, and are not part of the guiding social and economic system of values.

- The third core component of the domination social configurations—and these components are mutually supporting—is socially condoned and idealized violence. From child and wife beating to pogroms and chronic warfare, maintaining rigid top-down rankings of domination—man over woman, man over man, race over race, religion over religion, and so forth—requires a high degree of built-in violence, including the violence against women and children we here are working to leave behind.

By contrast, the core configuration of the partnership system consists of:

- A democratic and egalitarian structure in both the family and the state or tribe, and all institutions in between.

- Equal partnership between women and men, and, with this, high valuing of so-called soft or feminine traits and activities in both women and men, and in social and economic policy.

- A low degree of built-in violence; they have some violence, but it is not needed to maintain hierarchies of domination. Partnership oriented systems also have hierarchies, but these are hierarchies of actualization, where power—as we increasingly hear as we try to move again toward partnership—is not power over, but rather power to and power with.

Again, cultures that orient to the partnership side can in other respects be very different. They can be tribal, such as the Teduray of the Philippines studied by the UC anthropologist Stuart Schlegel; agrarian such as the Minangkabau of Sumatra studied by the University of Pennsylvania anthropologist Peggy Reeves Sanday; they can be technologically advanced societies such as Sweden, Finland, and Norway, which I will get back to.

Our Early Social and Spiritual Direction

I want to note that archeology, the study of myth, DNA studies, linguistics, and other disciplines are now documenting that for most of human cultural evolution society seems to have oriented primarily to the partnership side of the social scale.

I am not only speaking of the thousands of years when humans lived in foraging societies, which is now thoroughly documented, especially in the works of anthropologist Douglas Fry (co-author of my most recent book, Nurturing Our Humanity: How Partnership Shapes Our Brains, Lives, and Future, which will be published next year by Oxford University Press).

I am talking about some of our earliest farming societies. For example, the Turkish town of Çatalhöyük, going back over 8,000 years, where there are no signs of destruction through warfare for a thousand years; no signs of big disparities between haves and havenots in houses and grave goods; and, as Ian Hodder (the archaeologist now excavating Çatalhöyük) noted his Scientific American article “Women and Men at Çatalhöyük,” this was a society in which sexual differences did not translate into differences in status or power.

This kind of information may seem shocking because it has not been part of the historical canon, which still tells a very different story. But if we think about it, we’ve long had clues to this earlier time from some of our most ancient myths and legends from all world regions. For instance, in the Chinese Tao te Ching, we read of an earlier time before the yin or feminine principle was subordinated to the yang or male principle, a more peaceful and equitable time when the wisdom of the mother was still honored.

And right here in Ireland, we are now finding traces of this earlier, more woman and pace honoring partnership-oriented time—not just in Celtic settlements, which incorporated some of these earlier women- and nature-honoring spiritual and social traditions, but in pre-Celtic ones such as the Hill of Uisneach.

The Point-Counterpoint of Modern History

In fact, much that is happening today, including the global women’s movement, has very ancient roots. We do not have to start from square one.

Not only do we today know that the original direction of human culture was toward partnership, if we look at modern history through the new analytical lens of the partnership-domination social scale, we see that rather than being random or disconnected, all modern progressive movements challenged one thing: traditions of domination.

The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century rights of man movement, challenging the so-called divinely ordained right of kings to rule their “subjects;” the feminist movement challenging the “divinely ordained” right of men to rule over women and children in the “castles” of their homes; or the anti-slavery and later civil rights and anti-colonial movements, challenging another tradition of domination—the “divinely ordained” right of a “superior” race to rule “inferior” ones—these movements for social and economic equity and human rights challenge top-down rule. The peace movement and, more recently, the movement to stop violence against women and children—key to fundamental cultural transformation—challenge the use of force to impose one’s will on others. The environmental movement challenges another tradition of domination: the conquest of nature that, at our level of technological development, could take us to an evolutionary dead-end.

However—and this is critical—most of these movements focused on dismantling the top of the domination pyramid (political, economic, and religious domination), with scant attention to the pyramid’s foundations: the formative parent-child and gender relations, with all the implications for society at large.

Domination systems kept rebuilding themselves on these foundations in different forms—whether it was the totalitarian Nazi and Soviet regimes of the early twentieth century or the religious fundamentalism of the twenty-first, which is really domination fundamentalism seeking to push us back to a rigid, top-down family and society, the rigid subordination of women, and the use of fear and force to control.

I want to emphasize that it is not coincidental that a top priority for the Nazis was getting women back into their “traditional” place in a “traditional” family—code words for a top-down, male-dominated, authoritarian family where children learn that it is very painful to question orders, no matter how unjust. When Stalin came to power, he also pushed for a return to a traditional, male-dominated family. This was a top priority for Khomeini in Iran, and is today a top priority for fundamentalists of all stripes—be they Eastern or Western—who, not coincidentally, also believe in authoritarian rule in the state or tribe and in holy wars, as well as rigid male control over women in both the family and the state. Indeed, the focus on retaining or restoring domination in gender and parent-child relations is a hallmark of regressive regimes or would-be regimes.

However, ironically, many people who consider themselves progressives still view violations of women’s and children’s human rights as “just” women’s and children’s issues to be addressed after “more important problems” have been resolved.

Building Foundations for Partnership

It’s up to us—to you and me and our colleagues and friends—to change this major obstacle to moving forward. We have to join together to bring into both popular and academic circles the partnership system and the domination system, which show connections that are not visible through the lenses of old categories.

Our task is to usher in a whole new worldview in which matters that directly affect the lives, and all too often deaths, of the majority of humanity— women and children—are recognized as key to building a more equitable, more sustainable, and safer future. We have many new findings to show this, though they are still largely marginalized.

We now have women’s studies, men’s studies, and gender studies, but they are only a few decades old and are still not integrated into the mainstream curriculum—still marginalized—and we have to change this. We also have to bring the findings from neuroscience on the importance of early childhood relations into the mainstream curriculum and the mainstream conversations, and yes, of gender relations because these too are matters children observe early on which impact brain development. We also have to bring into the mainstream the findings about the partnership and domination system as two underlying social configurations that transcend our old social categories—categories that a colleague of mine has called weapons of mass distraction because they fragment our consciousness as they obscure the connections we have been looking at.

You can make a huge difference, so I want to end with four key interventions—four cornerstones for a more equitable, sustainable, and caring world.

The First Cornerstone: Childhood Relations

As I mentioned, we know from neuroscience that what children experience and observe in their family and other early relations directly impacts nothing less than how our brains develop, and these experiences and observations are directly shaped by the degree to which a cultural environment orients to partnership or domination.

Consider that when family relations based on chronic violations of human rights are considered normal and moral, they provide models for condoning such violations in other relations. And if these relations are violent, children learn that violence from those who are more powerful toward those who are less powerful is acceptable in dealing with conflicts and/or problems and to maintain or impose control. They learn this not only on an emotional and mental level but on a neural level.

This is why attention to childhood relations is so important, and why we need a global campaign to end the pandemic of traditions of abuse and violence against children.

The Second Cornerstone: Gender Relations

How a society constructs the roles and relations of the two basic forms of humanity—women and men—not only affects women’s and men’s individual life options, it affects families, education, religion, politics, economics; what we consider valuable or not valuable; and what we believe is moral or immoral.

As the global women’s movement spreads, more men are nurturing babies, more women are beginning to enter positions of economic and political leadership—but it’s much too slow. Also much too slow is ending the global pandemic of discrimination, abuse, and violence against women, which I have documented in many works.

What we urgently need—and again this will only happen if we make it happen—is a global campaign for equitable, nonviolent gender relations.

This takes us to the next cornerstone for a partnership society.

The Third Cornerstone: Economic Relations

The four cornerstones are interconnected and mutually reinforcing, which is why I want to start with our gendered system of values, and how the devaluation of women and the “feminine” directly affects a society’s general quality of life.

There is empirical evidence of this. Women, Men, and the Global Quality of Life—a pioneering study based on statistics from 89 nations conducted by the Center for Partnership Studies back in 1995—found that the status of women is a powerful predictor of a nation’s general quality of life. Since then, this has been confirmed by other studies, including the World Values Survey and the annual World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap reports, which show that countries with a low gender gap are also more economically successful (and if you read The RWN, you can find details about this).

One obvious reason is that women are half the population. But another reason is that as long as the half of humanity with whom values such as caring, compassion, and nonviolence are associated—the female half—remains subordinate and excluded from social governance, so also will these values.

Therefore present economic systems—whether they’re capitalist or socialist—are not capable of meeting our unprecedented economic, environmental, and social challenges. Both capitalism and socialism not only came out of industrial times, and we are now well into the post-industrial age, but both emerged during times that oriented far more to the domination side of the continuum.

For both Adam Smith and Karl Marx, nature was there to be exploited; they had nothing to say about caring for nature. As for the work of caring for people in homes, starting in early childhood, this so-called women’s work was for them just reproductive, not productive work.

So, while we want to retain whatever partnership elements there are in both capitalist and socialist theory, we have to go beyond both, to what I have called a caring economics. I realize that people do a double take hearing caring and economics in the same sentence, but isn’t that a terrible comment on how we have been socialized to accept that economic systems should be driven by uncaring values?

We have to change this, and a first step is changing how we measure economic health. Because we now know that if the value of the caring work in households were included, it would constitute no less than 30 to 50 percent of the reported GDP.

Actually investing in caring is very profitable, not only in human and environmental terms, but in purely financial ones. This takes me back to the Nordic nations, which were so poor at the beginning of the twentieth century that there were famines, but their subsequent caring policies were a key investment in what economists like to call “high-quality human capital.” Today, these nations not only have the lowest gender gaps but also regularly rank high in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness reports.

These nations—Sweden, Norway, and Finland—now have a generally high living standard for all, without huge gaps between haves and have-nots; they have far greater gender equity in both the family and society, so women are about half of the national legislature. As for violence, they pioneered the first peace studies and the first laws prohibiting physical punishment of children in families.

What we see here is strong movement to the partnership configuration—and a major part of this configuration is that because women have higher status, these nations accord higher value to stereotypically feminine traits and activities such as nurturance, nonviolence, and caregiving; they have very generous paid parental leave, high quality universally accessible childcare, elder care with dignity, and other caring policies.

And this partnership social configuration supports a more equitable, peaceful, prosperous, and sustainable way of life.

This takes me to the next cornerstone. Because you would never know any of this, would you, from our conventional narratives?

The Fourth Cornerstone: Narratives and Language

Old stories we inherited from more rigid domination times idealize conquest and domination—be it of people or of nature—as manly, desirable, and inevitable. These stories are not only not adaptive, they are not accurate. We humans have enormous capacities for consciousness, caring, and creativity, but these are inhibited or distorted in domination rather than partnership cultural environments.

So it’s up to us—to you—to change these old stories, and this is a major theme in all my books because we humans live by stories!

We also have to make changes in language. Consider what linguistic psychologists like Robert Ornstein point out: that “. . . language provides an almost unconsciously agreed on set of categories for experience, and allows the speakers of that language to ignore experiences excluded by the common category system.”

Given our domination heritage, it should not surprise us that the only categories in our language that describe gender relations are patriarchy and matriarchy. And what do they tell us? That our only alternatives are either men or women ruling. The language we inherited from more rigid domination times has no word for egalitarian gender relations, which is why the new language of partnership is so essential.

Conclusion

There is so much more I would like to share with you, but you can read my books, you can go to websites such as centerforpartnership.org and rianeeisler.com for more information, and more actions to take.

I want to close by reiterating that the struggle for our future is not between religion and secularism, right and left, East and West, capitalism and socialism, but in all these sectors between traditions of domination and a partnership way of life.

We can begin accelerating the shift from domination to partnership by focusing on two of the cornerstones for a partnership world: changes in gender and childhood relations, especially ending traditions of violence and abuse of women and children, which have maintained relations of domination and submission, not only in our families but in all our institutions. Because, again, what children experience and observe in their early years, the childhood and gender relations we have been discussing, is foundational.

We also have to pay attention to the other two cornerstones for either domination or partnership systems: the cornerstones of economics and narratives and language. All four are inextricably interconnected and must be changed from domination to partnership.

Cultures are human creations, and you can play a role in accelerating the shift from domination to partnership worldwide. Let us break out of the domination trance that makes insensitivity, violence, and cruelty seem inevitable, and use our enormous capacities for creativity—as well as for consciousness and caring—to build the missing foundations for that more peaceful and equitable partnership future we so want and need—for ourselves, our children, and generations to come.

Love you, Riane! We met at the NW Regional Conference for The Peace Alliance in 2008. I agree with all that you have said. I have another lens through which to look at the culture of control, domination and violence: the lens of addiction as a distraction from the horror of toxic shame that affects us all.

Thank you for shining the light of reason and empathy among us.