Thorns and Candy

Thorns and Candy

featured image | fszalai

Author’s note: What follows is a written conversation with the Colombian shaman Juliet Goméz and her partner Hernando Ruiz a few days after I had participated in their ayahuasca ceremony in Ecuador. The “flashbacks” I describe became so strong that it took me over two years to compile this piece.

HANNES

Dear Juliet & Hernando,

I will be writing in English, although the true poetry of the world is written and heard in all languages at once, a glossolalia that transcends the differences of languages and speaks directly to the heart.

One week has passed since we met, and I’m slowly coming back to normal—a new normal, indeed, and I agree that the experience has truly changed my life. Here in Mexico City, I keep having ayahuasca dreams and I encounter many similar patterns in my sensual experience, my daily rhythm, especially my thoughts. Sometimes, I wish never to have tried ayahuasca, to go back to the old normal; but there is also a new light that slowly unfolds.

What keeps returning and surprised me a lot is a terrifying darkness that surrounds all my memories of our experience. Although I felt very warm in your good company, as soon as the drug hit I found myself in an amazing techno club that, however, slowly turned into a laboratory for experiments on humans, a concentration camp, with medieval torture instruments: the jungle is hell, really really hell! And in my eternal suffering, I cursed you for bringing me into this, and I thought that you wanted to kill me for real.

In the end, you didn’t kill me, so in a way you saved my life. But I keep wondering whether this extreme suffering was a necessary aspect of the process. In the European context—with which I am more familiar—one may speak of catharsis as a spiritual cleansing through suffering, but I’m unsure whether such a concept is applicable here. In India, for example, there are similar concepts, too, but more central is eternal bliss, a state in which the mind transcends the difference between joy and suffering. To put my question more baldly: Must one go through suffering to gain eternal bliss? Or, as the writer Kafka put it: Does one have to suffer torture to finally shout out the truth?

No longer curses but best wishes,

Hannes

JULIET

Hi Hannes, thanks for writing.

There is nothing that we, as humans, can evoke in anyone. It is just the power of medicine that is expressed on different levels for each person. We must bear in mind that we have a long history, life after life, that has left its mark on the universe.

That record speaks of all our past mistakes, cruelty, violence, darkness. Maybe we forget it now, but the universe has the full recording of all those acts, individual and collective, which have become our karma, that is, our debts.

Ayahuasca is the Liana of the Resurrected. It is the thread that catches us from all the dark and deep lakes where we have been for ages and ages.

Human beings cannot imagine where they have been, life after life.

There are thousands of jails, in different states of consciousness, where we have sown evil. We will never find it outside ourselves.

With what you wrote to us, we understand that what you experienced under the influence of ayahuasca was a small moment in your own evil and shadow. What you sowed in the past.

There is no need to be afraid of this, or curse. It is better to thank – because little by little the light undresses you inside, with the opportunity to realize and do new things in the present. The thorns are the steps to ascend the stem, then reach the soft petals and pistils of the rose. This is divine knowledge: climbing with courage, until you reach the rose. Nothing is free, everything has a cost.

True happiness is not a human emotion that brings you pleasure, well-being or laughter. It is an elevated state of consciousness, which cannot be reached without knowing the thorns of the rose. Because even from the plants with the most thorns, beautiful flowers sprout.

It does not matter if the road has thorns, stones, pain, obstacles, difficulty. We must live it with intensity, since it is the narrow path that leads us to the light. But it is not suffering. It is only the path, with different nuances, colors and flavors: bitter and sweet.

As an initial treatment, we recommend people to approach the medicine of yagé (ayahuasca) at least seven times. We have in mind here the seven energy bodies, which is where all our shadow hides.

You have already seen and understood that medicine is not for the curious, but for all those who want to enter the university of higher spiritual studies, where nothing is written. Everything has to be felt on the skin.

Yagé medicine gives us wisdom about ourselves, but we must first pay a high and courageous price.

With patience, courage, dedication, respect, we can all achieve it.

Yagé medicine is liquid God. Once it enters our body, it never leaves. It stays in the form of consciousness, in your blood, your thought, your energy, your heart, your word.

That is why we understand that you were not mad at us. Perhaps you were just very far away and forgotten by God, due to ideas, concepts, theories or customs.

But you should always remember this:

“On the tree of life, we are just the leaves.

The power of the trunk and branches does not belong to us.”

A hug!

Juliet

Ceremonial Preparations at Sol Sanación

HANNES

Thanks for your soothing words. I can feel the light right now, and I remember that even in the process, at some point, I got in sync with the liquid god and with your help I discovered ways to open up rather than trying to control—the thorns never disappeared, but they somehow grew into the backyard.

There is a brilliant film called The Congress where almost everyone is high on psychedelic drugs and all humanity turns into a dystopian utopia in rainbow colors. Only the protagonist still cares about “reality,” and I never understood her because the wild reality out there feels so much more real than “reality” itself—and so much more on ayahuasca where every glimpse, every sound, every movement of my tongue or toe opened a new world for me—and still, there came the moment where I just wanted to return to my love and our little child: here, in Quito, Guanguiltagua; this reality, not any other, not for any price in the entire universe.

Infinite different layers of reality appeared on top of each other, inside each other, in countless feedback loops and endless spirals, which at every instant spiraled up themselves anew. I understood that subtle movements of my body and my mind could lead to very different avenues or regions of pure light where the masters of this sacred world reside, and that this life in chaos is not limited to drinking ayahuasca but simply goes beyond the so-called normal, sober mind.

My mistake was to forget that the physical effect of ayahuasca over time would disappear and once again I got afraid of being unable to return. I was afraid of becoming insane, and you saved me once again, which has some sense of irony because I’m writing on a book called Divine Madness: how could a title come any closer to what I witnessed with my body, mind, and soul?

You will be aware that drugs or sacred medicines are often associated with so-called hallucinations, but especially in the case of ayahuasca it is clear to me that—to the contrary—one witnesses the sacred truth of Being (ser) far beyond “reality,” which has been imposed to us by socio-political ideologies. As I see it, truth is not actually a world but rather a chaos of synaesthetic feelings, sensations, memories, and thoughts that constantly escape our human urge to control. In order not to get lost in it, humans have invented many theories and customs.

What do you believe? How is your own experience with ayahuasca?

Thanks,

Hannes

JULIET/HERNANDO

Hello Hannes,

It is very important to continue living human life in its absolute normality, without wanting to isolate ourselves from it. Many people seek extrasensory experiences in order not to live. This is a serious mistake.

It is better to follow the path of the balanced human being:

“With the heart in the sky and the feet on the ground.”

It is a balance that is difficult to understand and practice, but we can tell you that it can be achieved and—since you know us—we don’t look like mad people, haha!

Certainly, it is not a question of taking yagé medicine all your life, rather, it depends on what we are looking for.

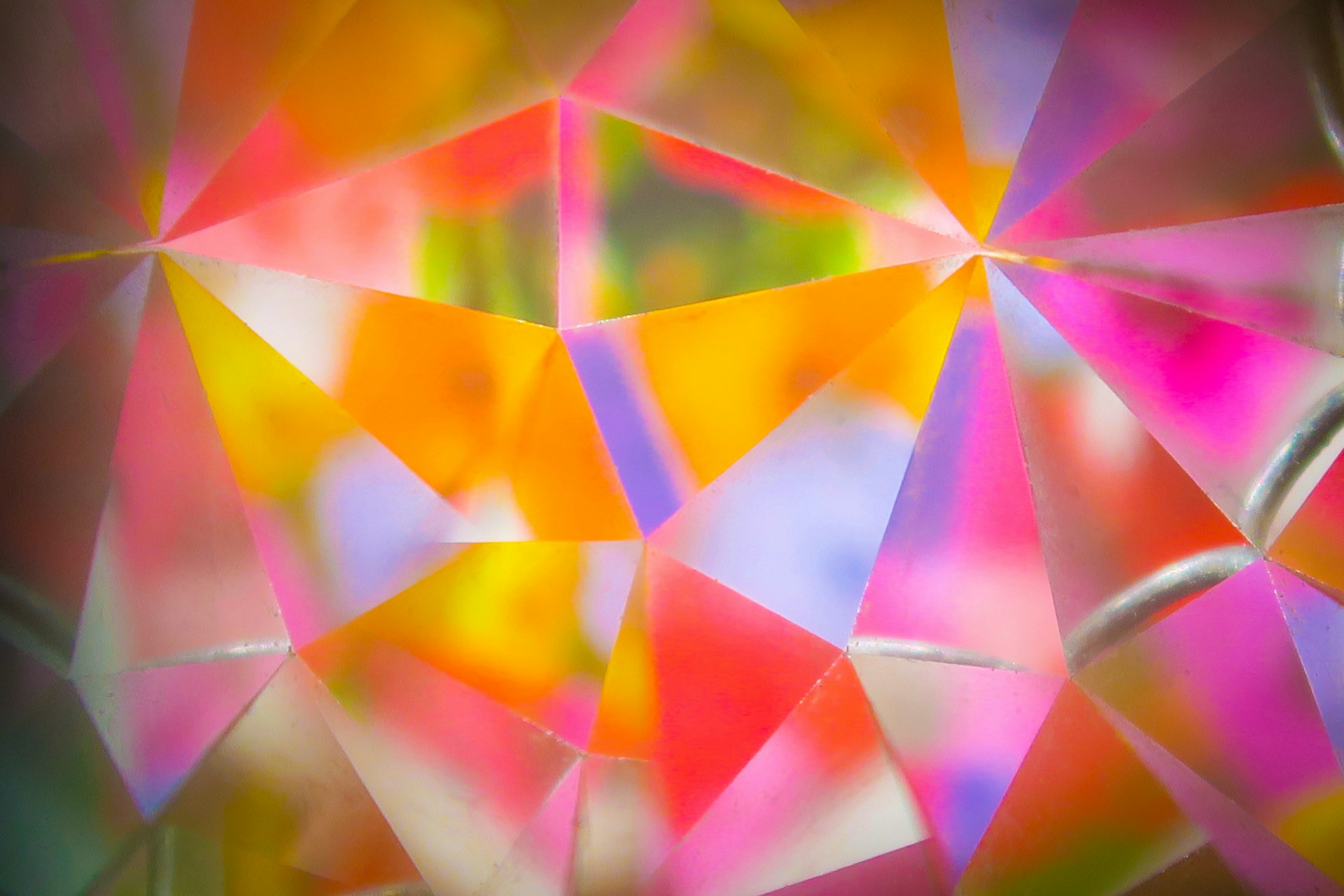

To that sensory experience you had, we say: “Candy experiences.”

We call it that because Mother Nature, for the first time in our lives, enthralls us with this endless range of colors, sensations, worlds, universes, etc., but little by little that must mature.

The natural and correct view is that experiences with medicine are rather introspective. May you abandon the vast universe, to know yourself.

Knowing more about ourselves and all those things that we must do, and also those that we must abandon, so that the mission of being is finally fulfilled, in the human body.

It is a long way to go…

The title of your book is very appropriate: “Divine Madness.”

It is beautiful, because precisely, you have to go through that divine madness, get drunk, and then return to sobriety in order to regain your sanity.

It is a constant taking and letting go.

That permanent impulse to control is produced by fear and separation.

Fear, because we do not want to feel or experience many things, not only under the influence of ayahuasca but also in everyday human life.

And separation, because by distancing ourselves from the divine source or God, we believe that we are in control of everything, forgetting that that place is occupied by the Big Boss of everything: that there is nothing to control.

Yagé medicine leads us to remember our forgotten nature, and the truth is implicit in this.

Truth

Love

God

Light

These are synonyms.

They are not words that mean something different. They refer to the same thing.

That is why for us it is clear that you do not have to believe in God. You only have to practice it. Day by day, second by second; in thought, word, feeling, and act.

In my case, yagé is everything I write to you and more.

From the very beginning, it led me to remember my nature.

Step by step, without explanations. (This is not so good for intellectuals.)

Only through the heart, little by little, have I unraveled the fabric of my life.

I have never stopped being human, and I have never tried to evade the challenges that this entails.

In the case of Hernando, it has been the same.

First, a lot of candy (lights, colors, fractals, rainbows, energy, portals, etc., etc.); then the experiences became more concrete, human, and familiar for both of us. Very specific.

We tell you: “The Tasks of Yagé Medicine.”

This speaks of a healthy process with the medicines.

Because we know people who have been taking yagé for 10 or 20 years and have not managed to get past the “candy,” they do not know anything about themselves.

A hug from the Ilaló volcano

Juliet and Hernando

HANNES

Hello Juliet and Hernando,

Thanks for taking the time for all these.

True, it’s not so good for intellectuals and, goddamn, I’m a philosopher, haha! But when I was recovering under the warm sunlight (sol sol, luz luz) and I was staring at the giant tree at Ilaló still spiraling about itself and sometimes staring back at me (!), I attained a strong conviction that I have to go this one step further than philosophy and mere intellectual discourse. All around the world there are unspoken practices which are sometimes called the “mystical”; your personal journey through the “sweets” of ayahuasca and your return to concrete everyday experience especially reminded me of Zen Buddhism: there is a saying that before the practice of Zen, a mountain is a mountain, and after several years of practice, a mountain is no longer a mountain, but at the end of the journey, a mountain is a mountain again.

Your conviction to truth/love/God/light is so strong, there is no comparison to any academic in the world, and your guidance of the ceremony throughout the night requires a strong sense of details and a skill that impressed me a lot; I truly loved Juliet’s performances, the use of different media including electronics. In my view, one can also see the whole ceremony as a genuine work of art—a true Gesamtkunstwerk, to make a joke about European opera.

What impressed me, too, is that you seem to be managing the entire “temple” on your own, which in English we call a grassroots project. When my art collective was still back in Athens, Greece, we were running a grassroots art space that hosted concerts, exhibitions, talks as well as workshops and ceremonies not very different from yours. When I was entirely engaged in my work, I often found it quite ridiculous to still label what we do as “art” or “philosophy” or “politics” or “religion” (we had something like a temple, too) but one sometimes has to keep these labels for the public, not least because of funding opportunities. After this, how do you feel about your label of a company for “mental health”? The price we paid is quite ok for visitors but seems a ridiculously small amount if one considers your hard work and the material required for the whole ceremony. Or do you feel closer to the label of the “temple”? Is there any difference for you?

Thanks and hugs

Hannes

JULIET

How great that you asked me.

Sol Sanación is a project from Heaven placed and inspired in my heart through yagé medicine. I never imagined having a healing center, it was not among my human plans. But God, always wise and silent, has a divine purpose for each person. Some find out about it, others don’t.

Without a doubt, in my case, the medicine was responsible for helping me recover that ancestral memory and leaving it as an indelible tattoo on my heart. At first, I thought that Sol Sanación was only a place where we offer our services, then we recognized that it is also we (Hernando and Juliet), as individuals, in a process of transformation, and that in the same way, spaces must go through a similar process. No space, company or temple can be transformed if the individuals that constitute it do not transform themselves.

Thus, we began a whole way of the cross (via crucis), but in the good sense of the word.

Before I met my husband, Sol Sanación already existed (2010 in Colombia). He came from working alone, with a lot of experience, but without a fixed place. It is very different from starting something new, because it was already about institutionalizing and professionalizing what we did, without losing the essence.

This task was not easy at the beginning, but little by little, this approach of maintaining the ancestral was born, but adjusted to human life: paying rent, public services, food, clothing, maintenance, and above all, CHARGING for our work. From the beginning, it was all very clear to me.

We always had to look for a place in the countryside that suited our needs. We have invested a lot of work in adapting to places that are not ours, we had to leave orchards, constructions, gardens and so on, in all the places we had rented.

Many tears shed, but we had to keep going.

In 2016, I had a vision that we had to leave Colombia for Ecuador; I wrote it in a notebook (as I always do), and in 2019 we managed to trust only in the voice of God and leave.

We sold our motorcycle, some household items, and the rest we gave to other families (bedding, kitchen items, etc.).

We only left with our clothes and our two dogs. We set off to a country where we didn’t know anyone, without any friends or family, and without enough money. We set off to begin a life that only God knew clearly. We did not.

The mission was to make an offering at the volcano Imbabura.

After many difficulties and abuses from Ecuadorians towards us, we finally achieved it! From that day on, many things began to unfold within us.

Sol Sanación Temple is a project from Heaven that must be given form on Earth. (If any psychiatrists listened to us, they’d tie us up… hahaha…)

That’s why it has been difficult, but we are not tired, because we know that it must be achieved.

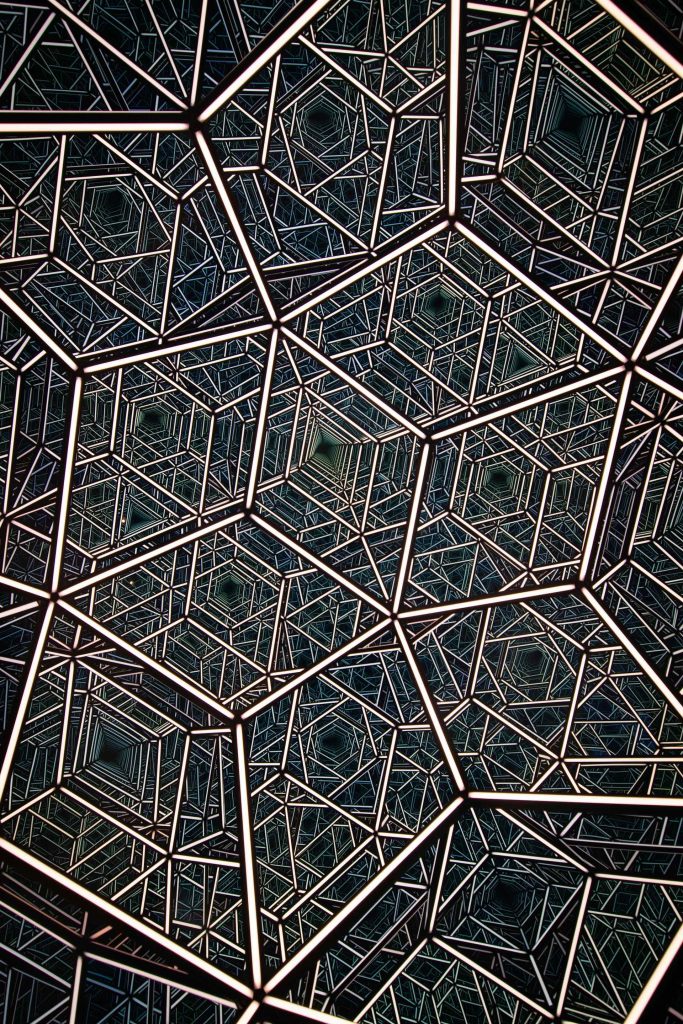

The logo of Sol Sanación represents the synchronization, meeting and order of all planets. The sun ahead of everything, generating order. And the mesh of hexagons that covers it represents the energetic molecular structure of yagé and San Pedro. (It can be verified only under the influence of the medicine.)

The logo of Sol Sanación represents the synchronization, meeting and order of all planets. The sun ahead of everything, generating order. And the mesh of hexagons that covers it represents the energetic molecular structure of yagé and San Pedro. (It can be verified only under the influence of the medicine.)

It comes to my heart in an orderly and clear way how I should do each thing, with the help of Hernando.

In the transformation process that I spoke about initially, the value is also very clear.

We have clarity of price, cost, and value.

An encounter with the sacred medicine of yagé is invaluable, because who could pay for a deeper understanding? Or a vast experience throughout the universe, discovering millions of truths?

However, we understood that humanly, we as teachers deserve a life in dignity through the exercise of our profession, and it is not frowned on by the spiritual world that we prosper with our work.

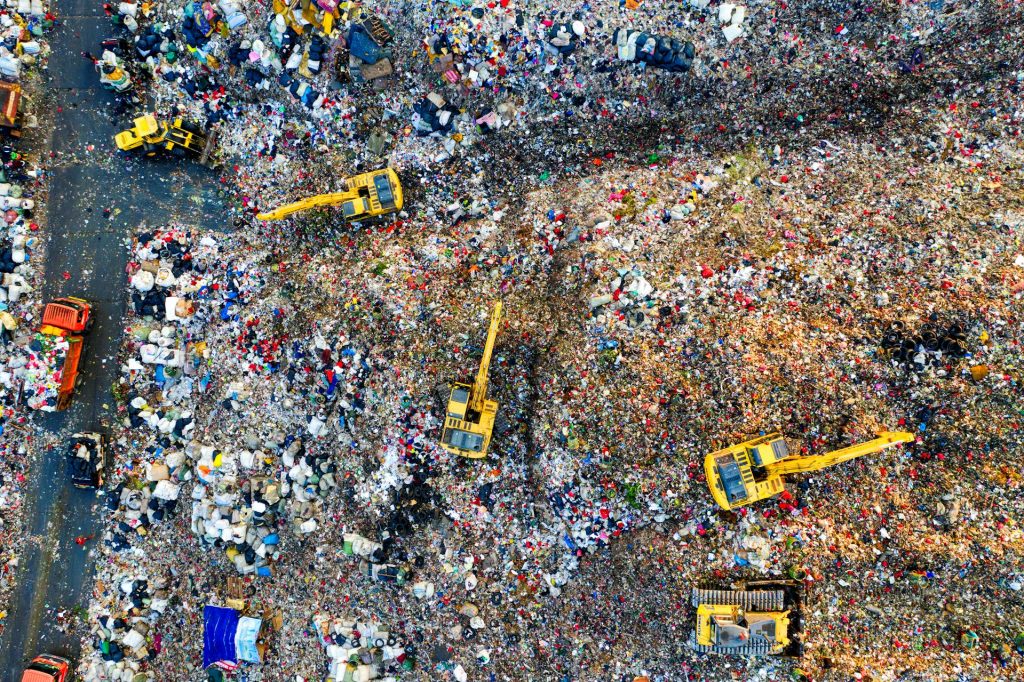

Moreover, this project aims to promulgate and preserve yagé medicine as a spiritual heritage of humanity. It is increasingly difficult to access the plant, since misuse, trafficking, and excessive cooking, plus harvesting without reforestation, are making it disappear from the jungles.

For all this infrastructure to function and be sustained over time, apart from doing things correctly, we must charge a fair value that covers all the needs of the place.

Now our view is very clear. All those difficult situations we have gone through are the thorns of the rose, indispensable to reach the petals.

There are three basic principles on which Sol Sanación is based: good birth, good living, good dying. And from these three principles opens the entire range of spiritual values and principles that every human being must give birth to in their hearts, to exercise the great gift of life on this earth.

A temple is the symbol of life itself, but that life inspired by the spirit, since the beginning of time. It is that life for which Sol Sanación has the mission of inspiring humanity.

We could not fit medicine into any human political dimension, but it is part of an organized structure in the Spiritual Kingdom. She is part of a hierarchical order, where she is the highest Queen in the world of plants. The others are no less, each one fulfills a beautiful function, but she is at the head, and this is already very transcendental.

However, it is clear that a shaman must actively participate in all aspects of life, without deviating from his purpose. The mango does not want to be a pineapple and the rose does not want to be a melon. Everything in its place, exercising its natural role. That is why we have the ability to lead a group of businessmen, executives, parents, young people, older adults, farmers, merchants, religious people, doctors, teachers, nurses, psychologists or children.

The light gathers and unites.

Darkness separates, divides, feels “different” or “special.”

Ancestral Medicine must break all those walls of ice, created by the human mind, and manage to melt them to find the essence in the eyes and heart of each person, until we can speak an intuitive language, where everything is known, everything is seen, everything is felt…

A hug

Juliet

Translated from Spanish by Hannes Schumacher

About Hannes Schumacher

About Juliet Gómez

Juliet Gómez was born in Colombia and she is the founder of Sol Sanación in Quito, Ecuador. She is a Reiki master and gem therapist with over 15 years of experience and a tireless spiritual seeker, inspired by the Sacred Medicine of Ayahuasca. In nature she encounters the purest expression of wisdom and the only means for learning essential shamanism. Based on this, she accompanies, leads and assists all processes at Sol Sanación, using simple, direct and didactic language as nature has told her.

The Mythology of Abuse

The Mythology of Abuse

Part I: Remembering and Naming the Truth

Some pieces ask to be written. Others insist. This one insisted.

The child within has insisted before, many times throughout my life. I’ve put her off. Focused on other injustices. Tended to other wounds. But she waits. My righteous inner child. The one who looks me in the eye and says, “If you don’t speak, who will?”

Yes, others speak. But not nearly enough. And not always like this.

This story is not just about me. It’s about a pattern. A mythology. One that distorts, denies, and displaces the majority of childhood sexual abuse. One that insists we only pay attention when the story is dramatic, the perpetrator a stranger, the memory vivid and linear.

But many of us live in the in-between. In the blurry memories. The subtle transgressions. The silence of trusted rooms. We oscillate between functional and dysfunctional freeze. We wonder: did it happen? Was it real? Why does it still live in my body?

We have a serious issue on our hands—one that affects far more than the category of “survivors.” One that shapes families, cultures, our collective nervous system.

For most of my life, speaking out was met with resistance. Anger. Institutional protocols. Surface-level concern for my performance, not my pain. The response was almost always: “That’s unfortunate,” followed by, “Now carry on.”

Still, my inner child insists.

This essay is for her. And for all of us. It is not a graphic account, but it is truthful. It explores how childhood sexual abuse occurs, why it persists, and what healing might require. It draws on personal memory, professional practice, and cultural critique. If you carry a story like this, read gently. Pause as needed. You are not alone.

And if you think this doesn’t apply to you, stay. Because the conditions that allow abuse affect us all.

The Violation Beneath the Surface

We like clean narratives. Monsters in vans. Clerical predators. Pedophile rings unraveled in primetime exposés. One-time events with clear beginnings and ends.

But most abuse doesn’t look like that.

It is quiet. Confusing. Repetitive. It happens in families, communities, under the gaze of people who should have known. It comes as boundary violations, emotional grooming, inappropriate touch disguised as affection. It thrives in ambiguity, where a child learns to doubt their own perception.

Sometimes, it is committed by women.

Sometimes, the violator is another child or adolescent reenacting harm done to them.

We need to tell these stories, too—not to collapse all distinctions, but to expand what harm can look like and how it hides, to pierce the veil of spectacle, break the silence of taboo, and name the epidemic we keep projecting as isolated outbreaks

Estimates suggest 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys in the U.S. experience sexual abuse before 18. The CDC reports over 40 million American adults are survivors. Experts agree this is an undercount. Disclosure is rare. Denial is common. Around 67% of victims don’t disclose in childhood. Many never do. Rates are even lower for boys, gender-nonconforming kids, and children of color. Factor in racial and economic inequities, and the underreporting isn’t just a gap—it’s a chasm.

Over 90% of victims know their abuser: parents, relatives, coaches, clergy, teachers, neighbors, or older children. Clergy abuse, while less common overall, accounts for a significant portion of institutional harm. Stranger danger and pedophile rings exist, but are rare. Wartime sexual violence is also real, but statistically represents a smaller share of global childhood sexual abuse.

Yet these more visible forms dominate the narrative—and that distortion undermines prevention. When we focus on spectacle, we miss what’s ordinary. Survivors go unseen. Silence grows from unsafety fed by fear, shame and discomfort, then amplified by proximity, and protected by status. Ironically, these are the very conditions that make abuse possible in the first place.

And the harm doesn’t stop in childhood. Survivors of early sexual trauma are at far greater risk for autoimmune disease, chronic pain, addiction, depression—even cancer.

The numbers are undercounted, but still overwhelming. What we lack isn’t data. It’s the cultural will to face it.

Cultural silence around children’s sexual development—combined with adult discomfort, religious shame, and refusal to acknowledge children as sovereign, intuitive beings—leaves a dangerous vacuum. In that vacuum, violations occur not just through what’s done, but through what’s withheld:

- Sexualization without guidance

- Disregard for bodily autonomy

- Denial of agency and awareness

These are not neutral omissions. They are betrayals. And they lay the groundwork for deeper harm—making it harder to recognize abuse when it happens, and even harder to speak it.

The abuse itself was one thing. The invalidation afterward was another. The silence from those who suspected. The denial from those who knew. The systems that responded with cold procedures instead of presence. That was harder to metabolize.

And yet…

Even when we’re not believed, something in us knows. The body knows. Healing often begins not with language, but with the felt recognition that what happened mattered.

I’ve seen this in myself. In clients. In community.

The pain is often not in the violation alone, but in the years of disconnection that follow. The belief that we are alone. That our needs are too much. That what we felt wasn’t real.

Every inner child I’ve worked with—healing from sexual abuse—has first needed the same things: a safe hug. To be seen. Heard. Believed. Protected.

When those needs go unmet, the nervous system adapts. Dissociation becomes survival. Spiritual bypass becomes identity. It’s easier to live in the clouds when your body feels like a prison.

But once safety is re-established (through presence, patience, and attunement), something begins to shift. Survivors often express their experience in layers, as the story evolves in how it remains held in the body. The body softens. Awareness grows. Over time, the nervous system begins to repair.

No client has ever shared their truth, processed it, and been done. This kind of wound doesn’t disappear—it scars. That’s true for individuals and culture. And as someone who carries a few scars, I can tell you: they don’t vanish. But with care, time, and community, they do fade.

When we begin to rest, eat, move, and express—something shifts.

We remember.

And with that remembrance, we slowly return to ourselves.

Part II: Cultural Mythologies and Systemic Betrayal

The stories we allow shape what we believe is possible—and what we deny.

Abuse is not rare. It is systemic. Cultural. Hidden in plain sight.

Myths center on individual pathology: the dangerous stranger, the rare tragedy. These headline stories are not the whole truth. Most violations occur in homes, schools, churches—systems that claim to care.

We fixate on elite villains because it’s easier than confronting ordinary people failing to protect their own.

I experienced this in graduate school. I attempted to embody and integrate the very frameworks we were studying—bringing my personal abuse story into a “coming out” paper that examined the codification of sexual trauma through the lens of performance theory. The response was not discernment, but judgment. My trauma was not engaged as material worthy of theoretical consideration. Instead, the critique focused on my failure to “perform” intellectual rigor.

Adding insult, the same professor who dismissed my effort enthusiastically supported another student’s decision to strip for the summer as research. Performative inquiry was celebrated. Vulnerable storytelling, even when academically rigorous, was met with grading rubrics and silence.

I now understand that for some, lived experience is only acceptable when properly distanced, abstracted, or packaged as spectacle. Institutions that market themselves as radical often cannot tolerate the intimacy of their own analysis when it is lived rather than performed.

This is not about one professor. It’s about our cultural inability to hold truth when it becomes intimate.

We live in a society where the body is either commodified or controlled. Christian doctrine and capitalism have left us ill-equipped to raise safe, sovereign children. Conservatives cloak repression in morality. Liberals outsource care to policy and data.

Children aren’t safe in a culture that sees them as pathology, purity, or projection. They’re safe when we honor their autonomy, meet their development with attuned presence, and confront our own histories.

Silence is not safety. Denial is not dignity. Institutions built on spectacle will fail to hold the unspeakable—unless we demand more.

Abuse is not an aberration. It’s a mirror of our power structures. Healing requires more than policy. It demands cultural reckoning and communal care.

We are not just protecting children. We’re unlearning what made us unsafe.

Part III: Healing and Integration

Healing from childhood sexual abuse is not linear. It doesn’t unfold through logic or will alone. It unfolds in the body—but not in isolation.

We are individual beings, but also part of a communal body. The boundary between the two is an illusion—measurable only by presence, resonance, and relationship.

To truly heal, we return to ourselves and to each other.

And the body remembers.

Most survivors I’ve worked with, including myself, have needed one thing first: to be believed. Before insight. Before forgiveness. Before reframing.

Because abuse is dissociative, we lose soundness in our own experience. We need a felt sense of being seen, heard, and held.

This is the foundation. Without it, healing becomes performance.

What I needed wasn’t correction or analysis. I needed someone to say:

“That was abuse. It was not okay. It wasn’t your fault. And it hurt you.”

“You are loved.

You are safe now.

We’ll keep listening.

As often as you need.

In all the ways you need.”

Sometimes, that someone was my husband. Sometimes, a skilled guide. Sometimes, a part of me finally strong enough to speak.

My own healing has arrived in waves: naming the harm in trusted spaces, recognizing how trauma reshaped my body and beliefs, and learning that the denial of what happened was often more damaging than the acts themselves. The invalidation, the silence, was the echo that stayed.

Somatic self-inquiry changed everything—especially Mary Shutan’s Body Deva Method. It taught me that healing begins not with mental insight, but with space for the body to speak. What I thought was self-blame turned out to be sorrow. What I called numbness was protection. The body doesn’t lie—but it speaks in layers.

To help clients access this work, I first introduced Deb Dana’s Polyvagal practices. What I found was that Polyvagal Theory didn’t just support the Body Deva process—it validated it. It gave language to what we were already experiencing: healing is not cognitive or isolated. It is physical. It is relational. We heal through the body, in the presence of others.

The third pillar, Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication, offers a way to speak truth without retraumatizing. Survivors are often deeply attuned to harm—their own and others’. We need language that honors both autonomy and connection. When rooted in body awareness and relational safety, NVC becomes more than a script. It becomes authentic, attuned, alive.

This is what HETA—the Harmonized Embodied Transformation Approach—is designed to do. It’s a living system of practice that honors humane embodied trauma alchemy: a slow transmutation, where unspoken truth, when met with presence, becomes clarity and connection. HETA is not a theory. Not a set of coping strategies. Not a mode of control. It is a way of being—one that helps us reclaim the parts of ourselves that went dormant. To remember that safety is possible again. And to return to the body’s most natural path to repair: play.

Because without play, healing becomes vigilance. Joy feels dangerous. But play is the nervous system’s language of trust.

And through play, we remember:

Connection, when safe, is sacred.

And so we rebuild. Not by erasing the past, but by holding it differently.

You don’t have to remember everything.

You don’t have to fix anything right now.

You begin by listening to your body, one breath at a time.

And in doing so, you begin to return.

To yourself.

To a world that is slowly learning how to hold what it once refused to see.

This is the truth we must honor now—not one of myth or silence, but of restoration.

About Abigail Testaberg

As co-founder of MagiCo, Abigail builds on the belief that science is magic explained. Her work integrates Polyvagal awareness, Body Deva somatic inquiry, and Nonviolent Communication—alongside digestive health and sacred medicine guideship when appropriate—to support healing, self-discovery, and embodied empowerment through principles of non-control. She guides individuals, families, and communities through frameworks like HETA and HOLISTIC180, offered not as protocols but as invitations to remember the body, repair connection, and orient toward what is life-giving. Her clients include parents of neurodivergent children, survivors of systemic harm, and those navigating collapse or emergence. Abigail lives off-grid in Mexico with her partner and children, where she tends land, stories, and the practice of becoming more human—together. She witnesses, writes, and guides with a commitment to honesty, nuance, and non-performative care.

Passing Time

Passing Time

featured image | Annette

The silent dark is broken by the padding of feet, drawing me slowly out of the depths of dreaming. The bedroom door opens a fraction, letting in a thin rectangle of light, then closes, drawing out the light once again. Something else has slipped in with the light. I strain my ears, listening for clues, but there’s only a sixth sense of another presence. Then comes a sigh, softer than the gentlest breeze, and a small sleepy body slips in beside me. Inside the covers, a cold foot presses on my belly.

On winter mornings the darkness lingers. I expect my children to wake with the light, later each morning, until the solstice, but that isn’t what happens. Instead they wake early, 6am, 5am, sometimes even 4am, and shuffle around the house in the cold, waiting for the sun, expecting breakfast and stories and warm fires from me. Every winter I tell them they mustn’t wake so early. Tell them it isn’t fair. Tell them I won’t. But I always do.

They try. For minutes at a time they hold back their restless energy and lie in bed, searching their senses for morning clues. They listen for the stillness before dawn, the distant rush of cars, birds stirring, a change in the feel of things. . . They listen until the exquisite pain of anticipation propels them out of bed and into the new day.

This morning though, I am given a reprieve. My son’s breath is steady, his mouth open, sleep has claimed him once again. It’s still dark and will be for hours yet. But I’m awake now and restless. I need the toilet. My arm is going numb where his head lies, cutting off my circulation. For a moment I wonder about that, how much heavier we become in sleep. How much there is inside our heads. How much we don’t use. I think about weight too, how there are different kinds of weight. The sort we measure on a scale, and the other sort. The heaviness that some people carry around them – their shadows filled with the past. I’m restless, but I’m putting off the inevitable. Whoever heard of waking a sleeping child? My oldest daughter cries out and I tense, but it’s quiet again. A passing fear.

There’s nothing heavy about my children, no shadows weighing them down, and I wish I could always keep it this way. I wish I could ward off the troubles of life, but we all have our own journeys to make. As Kahlil Gibran wrote so beautifully in The Prophet, ‘Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of life’s longing for itself. . . You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth…’

I am the bow, but not the archer. I’m not the maker of a destiny but the enabler. And what a responsibility that is. To be stable and strong for them. To give my children gladness, to teach them empathy and compassion and confidence. To show them how to find their way into the flow of life. To help them become truly human.

I am the bow, but not the archer. I’m not the maker of a destiny but the enabler. And what a responsibility that is. To be stable and strong for them. To give my children gladness, to teach them empathy and compassion and confidence. To show them how to find their way into the flow of life. To help them become truly human.

Or is it my children who are teaching me what I need to know? In so many ways they’re already wiser than me. I tell time by my children, counting the moments I still have. They tell time by embracing life. Days, months, years, slip through my fingers, while they fill each moment with themselves. I reach back into the past, strain forward into the future. They live in the now. Naturally. Easily. The way all wisdom traditions tell us we should.

I’m lying here awake, feeling the weight of my own shadows, my mind flitting from one thought to the next. I plan dinner, write a shopping list in my head, worry about the bills, panic about outfits for the school fancy dress ball, nudge my husband until he stops snoring and feel guilty because I’m not up already, using this rare solitary time for something more useful. But what sweet comfort, to be sandwiched gently between my husband and my son on this cold morning, feeling my son’s breath warm upon my cheek. How could I possibly regret anything so precious?

It’s no good though, my arm is hurting and I have to move it. I try to do this gently, hoping I can slip it out from under my son’s head without disturbing him. But he wakes and smiles at me, a face so clear I can see it in the almost dark.

‘Best mum,’ he says.

Then.

‘Mummy, let’s talk about mysteries.’

He’s sitting up, eyes bright, mind spinning with possibilities and I’m amazed at how smooth his transition is between sleeping and waking. I’m slow, dragging myself out of unconsciousness, grasping uselessly at my dreams which slip effortlessly away, tantalisingly out of reach. My brain stays fuddled, but he’s bright. He’s here. Now. And I want him to always be like that.

‘Mysteries?’

‘You know. . . Infinite space, imaginary numbers . . . What’s underneath a whirlpool? Inside a blackhole?

I think about blackholes. How scary they sound, the way they absorb energy, their appetite insatiable. Humanity is like that, sucking up the earth’s energy. There are individuals too, who deplete others of their life energy, sucking, sucking, trying to fill the empty space inside themselves. The more they suck the hungrier they are, that’s the irony of it. But for every vampire there is someone who radiates positive energy. Someone to whom others gravitate.

‘Mum,’ says my son, nudging me.

‘Most galaxies,’ I tell him, ‘have a supermassive black hole in their centre, a bit like a giant plug hole. Some of them are as big as billions of suns put together.’

His eyes are wide with wonder.

‘Is that as big as infinity?’ he asks.

‘No, infinity is bigger than anything.’

‘Like families,’ he says.

‘Families?’ I ask, puzzled, then wait while he thinks, loving the little furrow on his forehead and the faraway look in his eyes.

‘The way they go on forever, both ways. . . grandma and great grandma and us.’ He takes a breath. ‘And then we’ll have kids. . . and so will they. . .’

Slowly it’s dawning on me, the beautiful thing that my son has achieved. He’s connected space and time with infinity.

‘Yes!’ I say. ‘Yes, that’s exactly it.’

I clamour about in my memory for more wonders to feed my insatiable son.

‘As the stars and planets get closer to a blackhole they speed up, faster and faster, and time speeds up too, until a year is only twenty or thirty days. Imagine that, you’d have a birthday every few weeks.’

He laughs out loud at this but I can see his mind at work, calculating the present potential.

‘And there’s a theory that these supermassive black holes shoot out jets of matter, sometimes millions of light years long.’

‘Why?’ he asks.

‘I don’t know. Perhaps they throw up the bits they don’t want. Or maybe they recycle all the old negative energy and spit out fresh clean matter. Isn’t that a lovely thought.’

My son is quiet, he’s storing it, a special sweet to savour. He’ll want more, but I’ve reached the limits of my black hole knowledge and my daughters are waking. The stillness is being taken over by activity: lights flicking on and off, the toilet flushing, someone blowing their nose. It’s time to get up. Reluctantly I leave the warmth of my bed for the shock of a cold toilet seat. Then fumble about in the dark looking for slippers, woolly socks and a jacket. The chores are about to begin: breakfast, packed lunches, teeth, faces, clean undies, shoe laces. . . But first there’s the frosty trip outside for wood, the grass frozen solid, crunching under my feet, as I breathe steamy dragon breaths and ignore my shivering for long enough to stand staring up at the Milky Way, wondering at the universe once again after all these years of forgetting. . .

Another gift from my children.

All day

I hold them close.

About Rosie Dub

Dr Rosie Dub is a novelist (Gathering Storm and Flight), mentor, teacher, developmental editor and facilitator of Centre for Story (www.centreforstory.com), a platform for reimagining the world through story. Rosie has taught creative writing for many years in both the UK and Australia. She currently teaches on the MA in Writing program at Swinburne University in Melbourne. Rosie’s PhD research explored how purpose of story as a developmental tool. She shares her ongoing research in her Alchemy of Story workshop series and her twice monthly Alchemy of Story substack newsletter which explores how story forms us, how it frees us and how we can create our own transformational stories that help to reimagine our world. Rosie lives in Hobart, Tasmania.

The Fractured Fractal | Meaning Making in the Psychedelic Multiverse

The Fractured Fractal | Meaning Making in the Psychedelic Multiverse

This expansive essay explores the multiverse as both scientific theory and cultural metaphor, weaving together threads from quantum mechanics, psychedelic neuroscience, religious cosmology, and pop culture. Pick argues that the multiverse—a model of infinite, interconnected realities—mirrors the fragmented yet richly pluralistic nature of modern consciousness in the age of digital hyperconnectivity.

featured image | Daniele Levis Pelusi

Perhaps best known as a mind-bending premise within the big comic book film franchises, the multiverse is central to scores of storylines on- and off-screen, including Meow Wolf’s immersive arts funhouses across the southwest. The multiverse is, well, everywhere. Over the past few decades, the idea has evolved from a heady fictional concept to a valid cosmology supported by a number of scientific theories, including the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. In other words, the conceit that cleverly links many popular narratives may also describe the actual fabric of reality, presenting a dazzling vision of worlds without end that is at once exhilarating and bewildering. Somewhere in between, the multiverse serves as a versatile metaphor for our intensely hyperconnected, digitized lives, and also shares a certain curious resonance with what leading research reveals about the efficacy of visionary and altered states to increase neural plasticity and catalyze adaptive change. Whether or not it describes something real about the nature of the cosmos, the multiverse idea expresses something compelling about the human mind’s ability to expand beyond ordinary confines, forming new connections and exploring creative alternatives to previously intractable problems—all undoubtedly useful capacities for navigating our turbulent, “post-truth” times.

By multiverse I mean the concept of numerous, interconnected universes comprising something approaching the complete set of all possible worlds. This is distinct from the trusted sci-fi and fantasy trope of finite parallel dimensions or alternate realities, such as the Upside Down of Stranger Things, the literalized afterlife world of The Good Place, or the virtual-reality metaverse of Ready Player One. By contrast, the multiverse encompasses a dizzying array of branching universes that together form a vast intersecting web. In some versions, notably theories of the quantum multiverse, a new universe is brought into existence with every diversion in events, or with every quantum measurement, resulting in a fractal propagation of uncountable alternatives made manifest. The multiverse is therefore truly multi, an infinitude of possible realities, a garden of endlessly forking paths.

This Borges reference isn’t incidental—in several short fictions, including “The Library of Babel” and “The Garden of Forking Paths,” the acclaimed author describes infinite universes where “time forks, perpetually, into countless futures,” a vision that not only bears striking resemblance to the multiverse, but predates theoretical formulations of the idea by more than a decade. The history is interesting, because rather than originating as a serious scientific concept later filched for popular storytelling purposes, it’s kind of the other way around. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the word multiverse became associated with the various multiple-universe hypotheses that emerged as a more serious subject of scientific inquiry following discoveries of the accelerating expansion of the visible universe. At any rate, the fictional and scientific notions of the multiverse eventually converged, as multiverses sometimes do, to form the multivalent concept in popular use today as both mind-bending premise and useful metaphor, from the irreverent excesses of Rick & Morty to the heady maximalism of Everything Everywhere All At Once.

***

“Who are you,” the Ancient One inquires as Dr. Strange careens through a cosmic phantasmagoria of cascading dimensions, “in this vast multiverse?” The question comes about thirty minutes into 2016’s Doctor Strange, the first movie to introduce the multiverse idea to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and there’s no mistaking what’s happening—though energetically rather than pharmacologically altered, dude is tripping. That’s the thing about depictions of infinite worlds: from scientific cosmologies to satirical sitcoms, visions of the multiverse are routinely and almost universally described as “psychedelic.” This might just seem like a superficial convention for conjuring up colorful wacky multiplicity, but it actually reveals a much deeper intuition about the multiverse as a metaphor for uniquely mutable human imagination and experience.

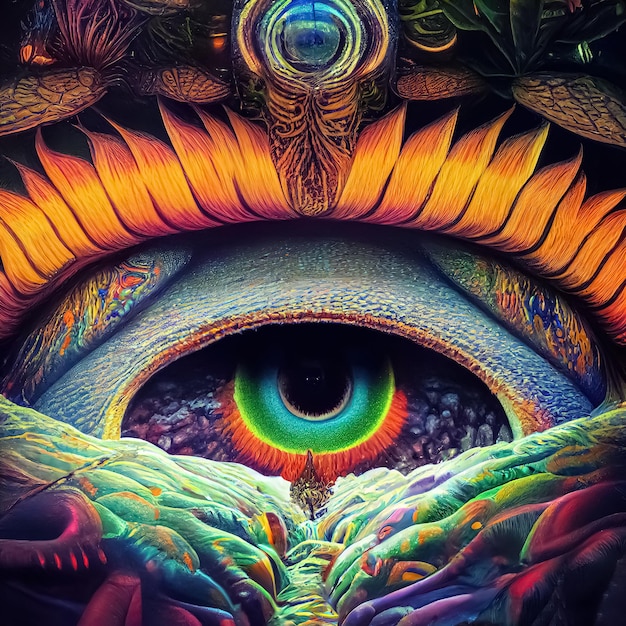

Psychedelic here typically refers to depictions of swirling, kaleidoscopic imagery comprising vivid polychromatic and geometric configurations that may initially appear chaotic but gradually deepen to reveal the formation of a larger, complexly-ordered whole encompassing all constituent parts in a harmonious patterning that is often suggestively self-similar at any scale, and therefore endless, as in a fractal, mosaic, or mandala matrix. When animated, such imagery is frequently rendered with a pulsing periodicity, as if it were alive, and shown to reveal or maintain its deep patterning across warping surrealistic transpositions of both time and space. In addition to sharing these qualities, Dr. Strange’s trip is illustrative because his journey across vast regions of telescoping spacetime isn’t simply a cosmic carnival ride, but a radical reorientation to the nature of reality and his own existence, whereby his supposed individuality is subsumed within the interconnected totality of the multiverse. Several times fragmented and reassembled, Strange tumbles through the black hole of his own pupil and appears reflected within the crystalline panes of jeweled galactic apertures as the Ancient One explains that “at the root of existence, mind and matter meet [and] thoughts shape reality,” giving rise to worlds without end.

Psychedelic here typically refers to depictions of swirling, kaleidoscopic imagery comprising vivid polychromatic and geometric configurations that may initially appear chaotic but gradually deepen to reveal the formation of a larger, complexly-ordered whole encompassing all constituent parts in a harmonious patterning that is often suggestively self-similar at any scale, and therefore endless, as in a fractal, mosaic, or mandala matrix. When animated, such imagery is frequently rendered with a pulsing periodicity, as if it were alive, and shown to reveal or maintain its deep patterning across warping surrealistic transpositions of both time and space. In addition to sharing these qualities, Dr. Strange’s trip is illustrative because his journey across vast regions of telescoping spacetime isn’t simply a cosmic carnival ride, but a radical reorientation to the nature of reality and his own existence, whereby his supposed individuality is subsumed within the interconnected totality of the multiverse. Several times fragmented and reassembled, Strange tumbles through the black hole of his own pupil and appears reflected within the crystalline panes of jeweled galactic apertures as the Ancient One explains that “at the root of existence, mind and matter meet [and] thoughts shape reality,” giving rise to worlds without end.

Such descriptions, then, actually are psychedelic, in that they recognizably correspond to both the visual and phenomenological contents of experiential reports with psychedelic substances and related meditative, mystical and non-ordinary states, as well as with the work of renowned psychedelic artists like Alex Grey and Pablo Amaringo. As with Doctor Strange, depictions of psychedelic experiences frequently feature human subjects fluidly interpenetrating, dissolving into, or otherwise merging with higher-ordered visionary realms that appear to overflow with multidimensional significance. While controversial, innovations in generative AI are further amplifying possibilities for hallucinogenic imagery, including the mutating fantasias of several recent psych rock music videos, which immerse the viewer in mind-bending excursions that can perhaps only be described as psychedelic. This isn’t to say that all trips are created equal, nor that they are even primarily visual or visionary. Heavenly or hellish, the subjective perceptual alterations occasioned by psychedelic experiences are astonishingly variable and unpredictable, such that one of the most conspicuous shared features of these depictions is multiplicity itself.

***

However nuanced the quantum multiverse and its related scientific theories may be, the basic idea is actually very, very old. Infinite worlds cosmologies of varying complexity can be found in the multiform dharmic traditions of the Indian subcontinent, including Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as the Atomist and Stoic philosophies of ancient Greece. Much like the assertions of modern physics, these cosmologies all emphasize a distinction between the fundamental components of reality and its perceived appearance. Perhaps the most elaborated pre-modern conception of the multiverse is that of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra, one of the principal works of East Asian Buddhism. A massive multi-volume compilation that is itself fractal in nature, the ‘Flower Ornament Scripture’ describes a vast “infinity of infinities” in which the pores of every enlightening being’s body contain “untold multitudes of buddha-lands filled with buddhas,” who likewise themselves contain a molecular multitude of worlds encompassing “courses of eons, as many eons as atoms in the untold buddha-lands in the succession of worlds.” Extending endlessly in both space and time, throughout the ten directions, it’s buddhas all the way down.

All infinite worlds cosmologies share something of this profound visionary potential, which can stretch our stargazing wonderment to the very limits, shrinking our narrow self-concern and enlarging our sense of possibility until it approaches the infinite. In their kaleidoscopic intricacy, the Avataṃsaka Sūtra’s inspired contemplations ultimately present the multiverse as a concept to carry us beyond conceptual thinking—as a gateway, a wormhole, a finger pointing. For most of us I suspect that the multiverse models of modern physics are similarly evocative, their branes, strings and manifolds taken less as intelligible descriptions of reality, and regarded instead with a kind of secularized awe that inclines toward the sublime. Physicist Brian Greene, who adheres closely to the theoretical science when describing nine types of multiverse in his popular 2011 book The Hidden Reality, affirms that such concepts require us “to abandon comfortable modes of thought and embrace unanticipated realms of reality.” However well we grasp the mathematical or explanatory validity of these theories, they nonetheless convey something appreciable, and essential, about the potentials and limits of human knowledge and perception.

In this way the multiverse idea can also be understood as a metaphor for things we know we can’t fully know, including all the ways that complex systems tend to be deeply interconnected, richly pluralistic, and subject to a variety of causes, conditions and possible outcomes. The presence of infinite possibilities is perhaps the most obvious reason why multiverse narratives are so ubiquitous: they invite our “what if?” speculations along not just one forking path, as is the case with alternate timeline classics like It’s a Wonderful Life and Sliding Doors, but across a tantalizing array of concurrent realities. By finding expression for every potential, multiverse narratives simultaneously indulge and assuage our doubts and fears in the midst of a rapidly-changing, politically-fractious, pandemic-destabilized world. The multiverse is itself an “infinity of infinities,” after all, and therefore provides an apt metaphor for the pervasive tangle of interdependent systems that shape our everyday experience yet elude our full comprehension.

This is perhaps nowhere more immediate than on the internet, where our direct experience is one of endless worlds within worlds, hyperlinked and fractal-dense, the next dimension only a click away. Scrolling even briefly through social media, we encounter a dizzying variety of viewpoints, every post a portal or attention-warping wormhole, a multiversal hall of mirrors. We take this kind of scattershot interdimensional travel for granted, yet research finds that mental health disorders, identity diffusion, and suicidality are all steadily increasing, particularly among young people, in what neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley describes as a growing global cognition crisis resulting at least in part from the fact that “our brains simply have not kept pace with the rapid changes in our environment—specifically the introduction and ubiquity of information technology.” The dopamine casino quality of the internet stimulates a fracturing of cognition that leads to measurable deficits in everything from attention and memory to creative thinking and empathic concern. In other words, these technologies tend to heighten our experience of reality as a disorienting expanse of possibilities that approaches both the infinite and the unknowable—a reality that our nervous systems increasingly struggle to make sense of.

***

In describing our hyperlinked world this way, I’ve also more or less outlined our current sociopolitical landscape. This is no accident—the internet-driven fracturing of cognition has profoundly destabilized both individual and collective meaning making processes. Speaking presciently in 1998, Terence McKenna described it like this:

“Technology, or the historical momentum of things, is creating such a bewildering social milieu that the monkey mind cannot find a simple story, a simple creation myth or redemption myth, to lay over the crazy contradictory patchwork of profane techno-consumerist, post-McLuhanist, electronic, pre-apocalyptic existence. And so into that dimension of anxiety, created by this inability to parse reality, rushes a bewildering variety of squirrelly notions.”

By “squirrely notions” he of course means conspiracies, cult beliefs and crackpot theories of all kinds, which McKenna also calls “epistemological cartoons.” Robert Anton Wilson more broadly refers to all worldviews as the belief systems or “reality tunnels” that enable each of us to organize and make sense of our world. The idea that we inhabit our own self-created universes isn’t new, but neuroscience now provides insight into the ways that our ordinary perception is a kind of “controlled hallucination,” a necessarily simplistic and incomplete map of reality based largely on perceptual predictions. Aldous Huxley famously describes ordinary consciousness as a “reducing valve” by which our brains selectively filter information and sense data to help ensure survival. In mistaking our mental models for reality, our limited worldviews become the totality of our individual and shared worlds, such that “from family to nation, every human group is a society of island universes.”

For all its connective magic, the internet exacerbates the fact that we functionally inhabit island universes. What this often feels like in real time is a continual inundation by myriad alternate realities and conflicting value systems that challenge any stable sense of what’s really real. Amidst this flood of possibilities, dogmatic worldviews tend to become very seductive—especially those centered around solidified personal identity—until we find ourselves beset at every turn by embattled positions and entrenched views. This phenomenon isn’t restricted to any one side of the political spectrum, and the surreal overlap in shared reasoning styles has become more apparent than ever, as Julian Walker insightfully outlines in analyzing the many strange congruities between the alt-right and New Age. Amplified by technology, this constant information overload has radically undermined cultural meaning making processes, replacing shared maps of reality with a paradoxical climate of acute paranoia, tyrannical certitude and outright magical thinking. Squirrely notions abound.

The result of all this destabilization is our current cultural pressure cooker, in which political division is no longer even superficially limited to issues of governance or red/blue affiliation, but is characterized instead by what Peter Limberg and Conor Barnes call memetic tribes, a type of ideological affinity group that “directly or indirectly seeks to impose its distinct map of reality—along with its moral imperatives—on others.” The social fabric is no longer made up of parallel island universes, but is instead largely defined by warring worlds vying to control the narrative and decide what our core social facts will be. These circumstances aren’t merely a reaction to increasing complexity, but have often been deliberately engineered, utilizing technologies and political tactics that take advantage of multiversal multiplicity to further destabilize reality for monetary or political gain.

The upside here (there is an upside, right?) is that our core social facts are no longer solely determined by a hegemonic consensus reality structured around capitalism, racism, patriarchy, colonialism, militarism and the rest. Those particular reality tunnels are still with us, and they’re still vying for ascendency as aggressively as ever, but they no longer hold the same monolithic sway. Engaged in an information exchange of unprecedented richness and diversity, a growing plurality of voices is offering innovative alternatives for social organization and cohesion. The abundance of multiversal possibility is profoundly double-edged, however, at once liberating (“It could be different”) and overwhelming (“It could be anything”). What we believe matters, and at a time when numerous planetary crises dispel any illusion of our separateness and challenge us with novel opportunities for unity and cooperation, we’re confronted instead with a vehement and divisive backlash that threatens to undermine democratic process itself.

This is often the immediate reaction to difficult realities, when destabilization leads to entrenchment and proliferating choice leads to inertia rather than action. Life in the multiverse can be a bit of a shitshow, in other words, as is expertly dramatized by many popular narratives. The directors of Everything Everywhere All At Once, for instance, overtly embrace the multiverse in search of storytelling “that can hold it all together” amidst a global meaning-making crisis in which cultural narratives no longer unify us. Making sense of reality in a “post-truth” world can be a formidable task, after all. So what can tales from the psychedelic multiverse teach us about navigating the garden of forking paths?

***

As clinical research over the past decade has helped bring psychedelics into the mainstream, demonstrating tremendous potential for their use as therapeutic medicines, it’s notable that a certain straightforward presentation of positive benefits is becoming something of a litany, as in this typical example from Newsweek: “people who take these substances have reported powerful mystical experiences that are often characterized by a sense of unity or oneness, a profoundly positive mood, a sense of ineffability, and transcendence of time and space.” While unity can be a significant feature of psychedelic experience, mainstream media descriptions commonly favor oneness and bliss over variability and multiplicity. Doing so can omit compelling insights about the brain and consciousness that have emerged from recent psychedelic research.

Robin Carhart-Harris’ entropic brain theory, for instance, posits that the default mode network, which normally regulates the brain’s ordered functioning and maintains an active sense of self, is temporarily disinhibited by psychedelic substances. The resulting increase in brain entropy and neural plasticity allows for higher information exchange, creative linkage and depth of experience, such that “the brain operates with greater flexibility and interconnectedness.” Carhart-Harris and renowned neuroscientist Karl Friston have expanded the entropic theory into what they call the REBUS/anarchic brain model, which proposes that in so doing, psychedelics can decrease hierarchical brain functioning and significantly relax the pathologic beliefs and assumptions that underlie mental suffering.

In Carhart-Harris’ work, entropy is synonymous with uncertainty, which our brains normally suppress when employing the heavily filtered, predictive processing that creates and maintains our island universes. By increasing the entropy of spontaneous brain activity, psychedelics can engender a more expansive conscious experience, relaxing the constraining influence of the entrenched, habitual views that shape many of the brain’s predictions. That this is possible does not mean that it’s inevitable, however, nor that it’s always pleasant—like early pioneers in the field, contemporary researchers continue to affirm the importance of set and setting, proper integration, and the value of ceremonial and therapeutic contexts for psychedelic use. “Psychedelic” is a neologism that means “mind-manifesting,” after all, and what’s being manifested appears to be the brain/mind’s potential to “spontaneously transition between states with greater freedom—and in a less predictable way,” such that access to the mind’s contents and capacities is radically enhanced. We might even say that the mind becomes more multiversal, more capable of engaging our dynamic and disorienting world with assurance rather than apprehension.

This may seem counterintuitive, given that multiversal complexity has just been suggested as a potential culprit in our ongoing meaning making crisis. But while perhaps more prevalent than ever before, complexity has always been with us. The issue isn’t necessarily the deluge of information itself, but our limited ability to make sense of an apparently chaotic expanse of seemingly contradictory or unresolvable potentialities, especially when exacerbated by the internet-intensified vortex that now shapes reality.

Our brains attempt to solve this problem by adopting simplistic stories or reality tunnels, in large part because the default mode network prioritizes the mental construct of a separate, individual self, which then serves as the central reference point for all conscious experience. Filtered this way, our picture of reality is, well, essentially a selfie, hyperfocused on organizing the limited set of past experiences, present beliefs and future expectations that defines our self-identity. This ordering principle has powerful adaptive advantages, but exerts excessive control on the brain, constraining perception and cognition. By catalyzing high-entropy mental states, however, psychedelics can heighten the brain/mind’s integrative and connective capacities to more readily accommodate multiplicity and uncertainty. As Michael Pollan explains, “the increase in entropy allows a thousand mental states to bloom, many of them bizarre and senseless, but some number of them revelatory, imaginative, and, at least potentially, transformative.”

In practical terms we might imagine something like a recent encounter I had walking down Denver’s East Colfax Avenue late one night, where I passed a barefoot young man splayed in a vacant doorway, underdressed for the season, the orange lighter and charred glass stem on the cracked sidewalk before him his only evident possessions, his nowhere stare not really seeing me, his mumbled request for change perfunctory, almost an afterthought. It’s one among many similar encounters in the space of a quarter hour, and on an ordinary night I might simply filter him out as “homeless” or “addict” or “mentally ill” without ever really seeing him, either. Just like that, we other—whether willfully or habitually, we all too easily ignore, dismiss, overlook, exclude. With a little more openness, however, I might instead recognize the evident suffering he’s carrying and the humanity we share, might even see that he could very well be my student or my son, could even be, down some darker timeline, me. And just like that, the moment flowers in a multiverse of possible worlds—the one where I befriend him; the one where I condemn him; the one where I report him; the one where I join him; the one where I suppress my feelings and do nothing; the one where the something I do is write about it. But more open still, and my habit of self-concern might further relax, dissolving my armor of individuation and enabling me to more deeply feel, and even to act upon, the kernel of care that has briefly burst open within me. Recognizing that we inhabit radically different worlds, my frames of reference fall away, welcoming a moment more immediate, crystalline, and maybe even shared. What then, among our multiverse of possibilities? Tomorrow never knows.

The prospect that greater cognitive flexibility can support deeper feelings of empathy and interconnectedness certainly resonates with recent research and reports of altered and mystical states, where experiences of transcendence, interfusion and universal love are not only prevalent, but often appear to occasion enduring functional changes. As entropic brain theory indicates, however, cognitive flexibility of this kind arises during states of increased ambiguity and generative disorder, which can be acutely distressing. Friston and Carhart-Harris acknowledge these risks by noting that “poorly integrated experiences could leave individuals awash in uncertainty and eager for solace in tenuous, or, worse, delusional beliefs that serve to stop-gap uncertainty.” Thing is, as we’ve already established, that’s precisely the state in which we find our current social order—as a simultaneously hyperconnected and haphazardly fragmented pressure cooker on overdrive.

It might seem contradictory to suggest that mental health can be improved by introducing still more cognitive disorder, even if only temporarily and in a regulated therapeutic setting. But again, as recent research indicates, the problem isn’t overload or uncertainty itself, but our brains’ limited tolerance of indeterminacy. The issue, in other words, isn’t too little order, but too much. All fundamentalisms and extremisms adhere to the brittle certainties of dualistic and dogmatic thinking, adopting highly controlled limits to impose an atrophied but internally coherent picture of reality. This includes cultic, conspiratorial and purity-centric beliefs across the spectrum—worldviews that have proliferated amidst the overwhelming irruption of multiplicity over the past few decades. It’s the planetary equivalent of a bad trip that has so far gone unintegrated, and resembles a phase of the psychedelic experience that Andrew Gallimore likens to channel surfing, when the brain begins to “move in a disorderly fashion through an expanded number of different patterns of neural activity … [as if] fumbling with the dial attempting to retune itself.” By loosening the default mode network’s habitual patterns, psychedelics not only subvert the brain’s tendency towards egocentric and ideological rigidity, but free the mind to discover new forms of meaning. And without both individual and collective expansions of meaning-making, we risk remaining stuck trying to solve problems with the same thinking that created them, or worse, remaining adrift in a relativistic limbo of perpetual distraction and inaction, as many multiverse narratives are inclined to warn us against.

***

In the 2016 film, after Dr. Strange is awakened to the vastness of the multiverse, he quickly masters the associated mystic arts and begins manipulating both space and time with the aid of energetic mandalas and other geometric sigils. It’s a superhero movie, after all, but one that playfully engages its many psychedelic tropes. For the 2022 sequel, In the Multiverse of Madness, Strange is able to freely travel between dimensions with the help of young hero America Chavez. Aside from one scene in which the two briefly traverse more than a dozen bizarre universes, however, the events of film mainly take place in a handful of recognizable alternate realities that conform to a conventional earth, heaven and hell schema. The film does explore some basic “what if?” themes, but the allure of infinite possibilities is unambiguously presented as treacherous. Instead, the multiverse idea primarily supplies a conceit for the combination of Marvel properties, serving up a facsimile of multiversal complexity that offers little meaning beyond its own increasingly entangled, self-referential spectacle—a problem openly criticized in later films.

Embracing both spectacle and complexity, the long-running animated series Rick and Morty gleefully exploits the multiverse idea to explore the storytelling possibilities and philosophical implications of infinite worlds. The show follows sociopathic mad scientist Rick and his earnest, anxious grandson Morty, who together form “a dialectic of damaged maleness,” as they cast about on interdimensional misadventures involving knotty sci-fi premises such as a love affair with a planet-wide assimilating hive-mind, an extraterrestrial counseling institute that materializes couples’ perceptions of one another, and a trans-dimensional city-state inhabited entirely by Ricks and Mortys from countless alternate realities. The show’s commitment to its story lines yields entertaining and mind-bending results, but for all the anarchic, parodic, and often cringey fun viewers might find, the characters (especially male) are generally not ok. Rick self-medicates while fiercely defending a narcissistic, nihilistic worldview, Morty bungles his own naive attempts at moral integrity with frequently catastrophic results, and his petulant father Jerry oscillates between withering self-doubt and willful denial. Prolonged exposure to multiversal relativism and the apparent absurdity of existence not only deteriorates everyone’s mental health, but often leads to further entrenchment within existing self-centered beliefs and other coping mechanisms. Rick and Morty cares deeply about investigating the possibility that nothing matters, and makes great effort to establish plausible deniability about this paradox, which lies at the show’s (sarcastically beating, dark matter-powered) heart. But for all its enthusiastic flash and cynical recoil, the show typically resolves with the family achieving domestic ceasefire and returning to the couch to watch TV together—less an integration of multiplicity than a retreat into familiarity.

As metaphor for our contemporary cultural cacophony, these multiverses pull few punches. Both the MCU and the world of Rick and Morty affirm the deleterious effects of information overload, existential uncertainty and a superabundance of possibility, so it’s no surprise that mental health and the pervasive cognition crisis are key themes. The “madness” of the Doctor Strange sequel refers to Wanda’s and Strange’s slipping sanity amidst the overwhelm of alternate realities, where they witness versions of themselves succumbing to brutality and destruction. For Marvel’s mystical superheroes, as for mad scientist Rick, these narratives emphasize the chaotic and reality-destabilizing consequences of such power, rather than simply its corrupting influence. These are essentially cautionary tales, though our protagonists manage to escape a more unpleasant fate by acquiescing to the strictures and conventions of their native timelines, presumably wiser in the knowledge that the nature of reality exceeds their understanding or control. That’s true enough, and an important starting point for sense-making, but beyond warning us away from similar folly, both story worlds fail to provide helpful strategies for skillfully navigating the continued encroachment of multiversal complexity into our everyday lives.

Other multiverse narratives take a different approach, however, mapping the same dangers but offering decidedly different responses. The multiverse idea is an essential connective element in the concept and design of Meow Wolf’s hugely popular immersive arts projects, including permanent installations in Santa Fe, Las Vegas and Denver, where visitors can choose to wander freely or attempt to follow each location’s unique puzzle-like narrative. Convergence Station in Denver, for instance, centers around the story of four worlds that have become entangled with ours in a mysterious cosmic event. Beset by psychic aftershocks, citizens’ memories are so scrambled that the exchange of “mems” forms the basis of the convergence’s economy. This sci-fi premise—perfect for a multi-level psychedelic labyrinth—supports an interactive narrative that unfolds like an elaborate scavenger hunt. Here, too, fragmentation and complexity are part of the story, but visitors are invited to creatively engage through spontaneous, childlike play, recalling lost memories or making new ones, and, like the convergence’s citizenry, actively piecing together or inventing one’s own meanings as part of the experience. Once inside, eyes alight, confusion gives way to a heightened state in which seemingly disparate worlds begin to cohere into something greater than the sum of their parts. Rather than shrink from ambiguity and overload, Meow Wolf prescribes full-scale exploratory immersion.

And then there’s Everything Everywhere All At Once, the acclaimed 2022 film whose title perfectly describes both the multiverse, by any conception, and the world for which the multiverse has become metaphor—the world we live in, where multiplicity is unavoidable and unfathomable in about equal measure. This multi-genre gonzo epic has been labeled sci-fi action comedy, though the London Review of Books perhaps more accurately describes the film as a “philosophical soap opera.” It’s a uniquely wild ride, by turns exhaustive and exhausting, where the multiverse also importantly serves, as Anne Anlin Cheng highlights, as metaphor for the immigrant Asian American experience, and by extension for the “the dislocations and personality splits” of many identities. Like Rick and Morty, the film takes the possibility that nothing matters as one of its central concerns, at once a psychological, generational and existential challenge depicted most vividly in the experience of teenage daughter Joy, but present in every character’s sense of failure and missed opportunity. There are fight scenes and goofball antics and poignant interludes, all tethered together with a head-spinning music-video momentum that blurs cosmic as the film progresses, coalescing in a googly-eyed psychedelia that contains multitudes.