Cynthia Anderson

Becoming Sequoia

Becoming Sequoia

To live for thousands of years,

you can’t be perturbed

by every insect or squirrel

or change in the weather.

When wildfire scorches

your skin, you heal and keep

going. Your intention protects

you like an amulet – you push

upward according to plan,

knuckled base nestled

against earth like a fist. You

follow the ways of a shaman,

transmuting air, rock, soil,

water. Your stamina could

build a world from ice.

You have no quarrel with

the sun, or with anyone –

radiating light from trunk

to crown, stretching taller

until one day, gravity takes

you down. Then, you commend

your body to the ground

among seeds already sown

and sprouting, no effort

wasted, birds and stars

sounding your name.

Cynthia Anderson lives in the Mojave Desert near Joshua Tree National Park. A Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net nominee, she has published nine poetry collections, most recently Now Voyager with illustrations by Susan Abbott. She is co-editor of the anthology A Bird Black As the Sun: California Poets on Crows & Ravens and guest editor of Cholla Needles 46. Visit her at www.cynthiaandersonpoet.com

Cynthia Anderson lives in the Mojave Desert near Joshua Tree National Park. A Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net nominee, she has published nine poetry collections, most recently Now Voyager with illustrations by Susan Abbott. She is co-editor of the anthology A Bird Black As the Sun: California Poets on Crows & Ravens and guest editor of Cholla Needles 46. Visit her at www.cynthiaandersonpoet.com

Lawrence Cohen

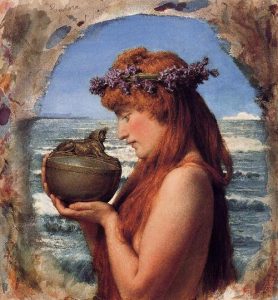

Pandora

Pandora

You know about her box,

So you think you know her.

Well first of all, it wasn’t a box, it was a jar.

An amphora.

So chew on that awhile.

I don’t know what viatical means

But I read it in a poem.

The poem was a gift from God –

If you accept that everything is a gift from – or to –a god –or two.

Shamans and charlatans

Twisting meanings.

Is it a braid, or a dreadlock?

You think you know which I mean to represent hope, and which sorrow.

I’ll spell it out,

I know you turn from ambiguity.

Pandora loosed the ills – it was her nature –

Beautiful Disaster.

No, she was just curious –

“Whatever you do, don’t open that box.”

They must think we’re all toddlers on this bus

And they – the gods – our desperate parents.

So read the Greek myths for revenge,

The sutras for sleep.

Read the Koran for stories of Moses.

We must stick together, with the gods so vengeful.

Lawrence Jack Cohen is a psychologist and author. His books for parents, including Playful Parenting and The Opposite of Worry, have been translated into 18 languages. He and his wife have two grown children. They live with their son and granddaughter in Portland, Oregon. Learn more about Larry at playfulparenting.com.

Lawrence Jack Cohen is a psychologist and author. His books for parents, including Playful Parenting and The Opposite of Worry, have been translated into 18 languages. He and his wife have two grown children. They live with their son and granddaughter in Portland, Oregon. Learn more about Larry at playfulparenting.com.

John Laue

At the Zen Garden

– Huntington Museum Grounds

Pasadena, California

Strangely comforting

these single circles

on the still pond’s surface.

They occur like phantoms,

grow, and then are gone.

There’s no apparent cause:

no rocks or raindrops

break the surface tension,

no bubbles from the bottom,

neither koi nor water skaters,

only sky-lit circles

that arise from calm,

subside to calm again.

We leave the place

with no more answers

than we had before,

but more aware of mysteries,

more inclined to let things be.

John Laue, teacher/counselor, is a former editor of Transfer, San Francisco Review, and Monterey Poetry Review. He has won awards for his writing beginning with the Ina Coolbrith Poetry Prize at The University of California, Berkeley. With five published poetry books, the last A Confluence of Voices Revisited (Futurecycle Press), and a book of prose advice for people with psychiatric diagnoses, he presently coordinates the reading series of The Monterey Bay Poetry Consortium.

John Laue, teacher/counselor, is a former editor of Transfer, San Francisco Review, and Monterey Poetry Review. He has won awards for his writing beginning with the Ina Coolbrith Poetry Prize at The University of California, Berkeley. With five published poetry books, the last A Confluence of Voices Revisited (Futurecycle Press), and a book of prose advice for people with psychiatric diagnoses, he presently coordinates the reading series of The Monterey Bay Poetry Consortium.

Rebecca Smolen

Intentions

After listening to protein spikes of COVID-19 translated into music by an MIT engineer and colleagues. (https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/scientists-have-turned-structure-coronavirus-music)

so much limits our sight, how

so much limits our sight, how

our brain has learned to convert that information

into something we can perceive—

but sound? sound can come at us from

all directions, be felt on our skin, through

our bones, even blur our sight without much

effort. when enhanced, the softer chords get

louder, the unheard become known.

as a child, I’d watch the scroll of a music box.

each bulge hooked onto metal fingers, let go &

would sing. mesmerized, I loved the anticipation.

each spike a different size, timed release to

perfection. some had singing bowl resonance.

I’d lay my child-fingers on them to feel

each chord ignite. when my mother would leave

her tweezers out, I’d bounce them on the table,

see how long I could hear their tone;

how long my ear would hold onto it before

it slipped away. I’m sure traumas don’t start

that way, don’t intend for it to hurt.

what if this virus has come to humans with

a less destructive intent, more to hear

its own music? what if its language is more

about compatible survival & a desire to share

the beauty it can hear? Could an understanding

ever feel blameless?

Rebecca Smolen is a Portland-based writer who grew up on a dead-end road in New Hampshire exploring drainage pipes and pond-life. She leads generative writing workshops using the Gateless Method and views writing as a form of healing. Her poems appear in Feminine Collective, Cirque, Tiny Seed, and The Inflectionist Review. Her chapbook, Womanhood and Other Scars, was published by The Poetry Box in 2018 and her full-length collection, Excoriation, is forthcoming this year.

Rebecca Smolen is a Portland-based writer who grew up on a dead-end road in New Hampshire exploring drainage pipes and pond-life. She leads generative writing workshops using the Gateless Method and views writing as a form of healing. Her poems appear in Feminine Collective, Cirque, Tiny Seed, and The Inflectionist Review. Her chapbook, Womanhood and Other Scars, was published by The Poetry Box in 2018 and her full-length collection, Excoriation, is forthcoming this year.

O M G ,LAR

You are so multi talented, it’s hard to keep up with you. I can see your mind hopping from THOUGHT TO THOUGHT….

YOUR SMILING FACE, LIGHTS UP YOUR PICTURE, AS WHEN I PICTURE YOU IT IS WITH THAT WARM LOVING SMILE.

NOW WE HAVE ANOTHER DIMENSION TO YOU.