This episode of Deschooling Dialogues features Kumu Ramsay Taum who shares deep insights on Indigenous sovereignty, the colonization of Hawai‘i, the sacred meaning of Aloha, and the necessity of restoring ancestral wisdom in a consequence-blind culture. This living transmission of relational intelligence calls us to remember our responsibilities to land, lineage, and Life itself.

DESCHOOLING DIALOGUES

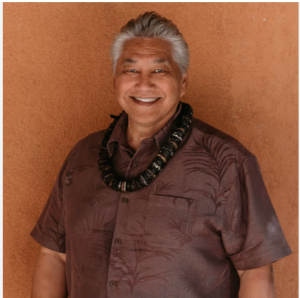

Episode 10 – Alnoor Ladha with Kumu Ramsay

This dialogue took place at Tierra Valiente, a post capitalist experiment in the northwest jungle of Costa Rica. Kumu Ramsay Taum held a gathering with Dine elder Mona Polacca on “Living our Sovereign Nature” in April 2025.

Alnoor Ladha (AL): Welcome to the Deschooling Dialogues. This podcast is a co-creation between Culture Hack Labs and Kosmos Journal. Culture Hack Labs is a not-for-profit advisory that supports organizations, social movements, and activists to create cultural interventions for systems change. You can learn more at culturehack.io.

Thank you to our editor and producer, Eber Rodriguez.

I’m your host, Alnoor Ladha. Today, my guest is Kumu Ramsay. Kumu is a peacemaker, a community leader, a non-linear systems thinker, a bridge builder, and a community navigator. Kumu is the director of the Pacific Island Leadership Institute at Hawaii Pacific University. It’s an honor to have you here with us at Tierra Valiente in Costa Rica.

KR: The honor is mine and the privilege. Thank you so much.

AL: We just came out of a very beautiful week of teachings from Kumu and Mona Polacca, who’s another elder from Turtle Island. Perhaps you could say a little bit about yourself and introduce yourself, any aspect of your journey that would be relevant to the audience before we go into content lines.

Kumu Ramsay (KR): Well, thank you again for this opportunity to share in this way and extend the sharing that went on this week. We’ll call it teaching, but it was really more sharing. My students and my teachers give me this honor of being called Kumu, this notion of resource.

We have a responsibility of connecting ourselves back to this natural and spiritual intelligence. But my parents gave me the name Ramsay. Well, my daughter calls me dad, and hopefully my granddaughter will call me something that will be not only memorable, but hold me accountable. And I think, if anything, that’s the underlying message to being Kumu – accountable, honest, transparent. But also, we say kia’i, a guardian.

And so in sharing this information that’s been passed on to me by elders, also donning the responsibility of a lineage carrier. If there’s anything else, it would be that, maintaining the values, principles, and practices of the various ancestors and their practices. And so that’s what brings me here to this ‘āina, this land to connect with it and its ancestors. It really acknowledges the fact that we’re all from the same family, same Mother, we just grew up in different rooms with a different view. I just happened to have the view of the Pacific living in the archipelago, Hawaii and the Hawaiian Kingdom, and being able to experience Mother from that perspective. To be here in this part of the world is being able to be with brothers and sisters.

AL: In this podcast, we’ve interviewed Tiokasin Ghosthorse, who’s a Lakota elder, Jess Hutchings, who’s Māori elder, and Vanessa Andreotti who’s half Guaraní from Brazil. But the context of Hawaii is very different and very specific. This is a sovereign nation that was annexed by the US over 100 years ago and brought into the fold of the empire. The changes have been rapid and they’ve been recent. And so maybe you could just give us a little bit of context on the Indigenous perspective of Hawaii and its relationship to capitalist modernity.

KR: Yes, the rooted culture versus the host culture is what we refer to ourselves as Kanaka Maoli, the first people of that particular place. And we are Polynesians at large. We live in Polynesia. But the term Hawaiian is really a nationality while the indigeneity, the Indigenous culture that had been there and people, we refer to ourselves as Kanaka Maoli.

The Kingdom of Hawaii was established as a constitutional monarchy in 1840 by King Kamehameha III, whose father Kamehameha Ekahi (the first), or the unifier of the islands, had taken what had been multiple generations of fighting, war and feudalism to create peace for the first time in many, many generations when he unified the islands around 1795. This is following the first visit by Cook in the western world.

Kamehameha III established the constitutional monarchy, which acknowledged, one, the Indigenous Native people of the place, but anyone that was really subscribing to and living by the values, the principles of what we now refer to as Aloha, but living in relation with Hawaii, the āina, the land. The Hawaiian Kingdom, the subjects, those members of that crossed many cultural and ethnic boundaries. The term Hawaiian is that unification.

In 1893 American businessmen, plantation owners that had moved to the islands, in many ways because of what was going on in the continental US, which was of course the slavery and the freeing of slaves, then came to Hawaii, and some of them were the descendants of original missionaries. They developed sugarcane plantations. And in order for them to continue their way of being, they needed to overthrow the government.

Queen Liliuokalani, our last queen, experienced the treason of her own people in this case, because these were Hawaiians by nationality. They overthrew the government in 1893. And 1898, a self-imposed government called the Republic worked with the United States towards what they would call an annex.

There is a false pretense that Hawaii was annexed at that time, and later in 1959 became a state through a plebiscite, a so-called self-determination vote. The reality is that’s never really happened. There is no annexation treaty between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States because the Hawaiian Kingdom did not have representation. The Republic was not given authority, so the sovereign still exists. Sovereignty still exists. In 19…

AL: Sorry, before we go there, who voted in the plebiscite?

KR: That’s important to note that the plebiscite in 1959, according to international law, menat whoever the people of that place were would have an opportunity to vote for self-determination. We want our governance to be this way versus something else. In 1959, the only people that could participate in that vote were United States citizens who had lived in Hawaii for more than a year.

From 1898 when it became a territory under the false pretense of an annexation, anyone that was an American citizen in the territory, or their descendants, could then vote or register to vote and anyone that had moved to Hawaii within the year prior. Those were the only people that could participate. Hawaiian Kingdom subjects and others who were not US citizens had no right to vote.

At the time, of the 600,000+ residents of Hawaii at the time, only 174,335 were registered to vote, and of that only 147,078 people voted for statehood. The percentage of people that actually participated voted for statehood was less than 24%. The historical record says “94% of the Hawaiians” voted for statehood, but in this case “Hawaiians” are defined as anyone living in the archipelago in the same way I would be called “Californian” if I lived in California or Floridian in Florida, etc. All US citizens living in the Hawaiian archipelago at that time were considered “Hawaiian.”

AL: And Indigenous Hawaiian people were not allowed to be US citizens?

KR: We didn’t participate. We weren’t US citizens. In order to be a US citizen, you had to give up these other things, your previous identity or you had to meet certain standards and values. That was not the case.

The only people that participated strangely enough were US citizens who got to vote between remaining as a territory of the United States, or becoming the 50th State of the United States. Well, surprise. Guess what? They voted to become a state. And the Indigenous Native people – Native, again, being born of that place, really had no say in it. For all intents and purposes, Hawaii and the Hawaiian Kingdom has and continues to be under occupation for 132 years. That’s where we are today.

In 1993, there was an acknowledgement 100 years after, 1893 to 1993. The United States established another resolution called the Apology Bill, Public Law 103-150. That law or that resolution apologized and acknowledged that the United States did participate in and support an illegal overthrow of this place, acknowledging that no one ever gave up their sovereignty.

Fast-forward, it means the Hawaiian Kingdom, the first non-European, independent nation state really continues in continuity as an independent state. However, we’re living under occupation by the United States, which is stated in their own Apology Bill.

The de facto government there is the state of Hawaii, which was given life by the United States, providing them with access to our resources and our land as well as passing on power of governance. What we know in international law, you can’t give what you don’t own. The United States had no ownership, therefore it could not pass that on the state of Hawaii.

The state of Hawaii as the de facto government is really making it difficult for the de jure government, which would be the Hawaiian Kingdom’s constitutional monarchy. That family, the successors of that continuity of governance, still exists, though they may not be recognized by the United States.

That’s what we have going on in Hawaii right now. And given what’s going on in the world, the opportunity to re-establish the fact that the international government, or at least the United Nations at some point has acknowledged that this is going on. Whether or not has the teeth or the power to restore that is another thing.

But where we are right now is acknowledging our internal sovereignty while everyone’s talking about external sovereignty. And this week we met here was really about living into our natural sovereignty as humans in relationship with our natural places.

AL: In the face of this 130 year plus occupation, how have Indigenous Hawaiians preserved ancient ways of knowing, being and relating to the world in the face of the onslaught?

KR: Yes, well, there’s a lot of assimilation that has happened. There’s some of us that are living what we call a survivor’s culture, whatever we could maintain in this onslaught of Westernization and denationalization from an educational standpoint. There are some families, individuals who maintain these knowledge bases, these wisdoms.

I’m fortunate to be a descendant and a lineage carrier selected, trained, mentored by some of these families in the warrior arts, the healing arts, the language arts, those kinds of things. But for all intents and purposes, the assimilation has been wide and deep. We have a number of people who are just very confused about their identity, especially those who have volunteered to participate in the defense of the country called the United States.

AL: Veterans.

KR: Veterans. Right. The difficulty there, of course, is they have established a commitment to Uncle Sam and are now faced with the challenge of supporting the Mother Kingdom, Motherland. And so now you have this tug of war. Oddly enough, it’s a family fight, and yet it’s my adopted uncle that is now demanding loyalty while Mother is sitting there trying to survive. If there’s one way to explain the dynamics, consider that.

As one of my colleagues would say, the analogy would be believing that you were adopted and living an entire life thinking that you’re adopted, and then one day find out that you’ve been abducted. All of the values of life, of making good, clear decisions are now questionable because the thief who has taken me from my family has been my mentor.

How can I trust my decisions now? How can I trust my beliefs? How can I trust any of that? You have a situation where people can’t trust themselves. We have to turn back to those things that we can trust, which is hopefully that knowledge and that wisdom.

We’re reintroducing ourselves to that on our own terms, not by the definitions of others. And that’s where the denationalization comes in, where they denationalize us by taking away our language, taking away our practices, forcing us into following certain practices and rules, even to the point where I was a beneficiary of a particular school designed to support Native Hawaiian children, but in reality what they’re doing was going around to the community, just like cutting the head off a snake so it doesn’t bite you later, finding all of those individuals who may have actually been of descent of chiefs, the true leaders, taking them and placing us in an institution as education.

Anyone that might be able to lead an uprising and edified our leadership put us behind this gate, said, “You are the leaders.” We’re still chiefs, fire chief, police chief, chief bottle washer, whatever it is. We still carry the titles, but we are the chiefs inside a system. We’ve actually become the supporters of the very thing that took our country. And so that too becomes a trauma. How do you live into your true identity?

The restoration and the reintroduction of these practices is where individuals like myself find ourselves today, fortunate that there were elders who maintained this and have been very careful about protecting and preserving these things. But in the absence of that, we lose those things. They take it with them.

If there’s any recommendation I make to our youth today, what we call our Opo, is that if your grandparents are still around, make a connection. Make yourself available so that they can share that with you. Otherwise, they’re going to take it. And we’ve already lost so much. And we know that when one elder leaves, a library leaves. It’s not a book, it’s an entire library. And the memory and what’s still stored in our waters, in our mountains, in our forests, it’s still there, but if we don’t know how to commune with it, we don’t know how to communicate, which is a difficult thing. It’s like standing in a library of books and not knowing how to read. Don’t know how to read the contents, the index, you don’t know where to start. You’re surrounded by information, but you have no way of accessing it.

AL: So what does the decolonization/re-indigenization movement look like and why? What’s the texture of it right now? How would you describe it?

KR: Well, much of it has to do with the very visual arts, the physical arts, the dancing of Hula, the singing of the songs, the restoration of chance when we go into the forest, all of those things that restore not for performance purposes, but for communion purposes.

The restoration of the language was critical because in the language is the science of knowledge transfer. It’s not just communicating, it’s communing. That language is a spiritual language. Every time you utter that sound with intention and emotion to support the outcome, you’re creating things. There’s been a restoration of that, a reclaiming of that, and of course a perpetuation of that. Whereas in 1978, we had very few Native speakers where we’ve established schools where now we’re graduating a 12-year program where they’re actually learning, restoring, reestablishing their language in contemporary space.

The risk, of course, is that this mindset is still being driven by the Continental mind rather than the Island mind. I say the Island worldview versus the Continental worldview, which is different than saying Western versus something else. We recognize that we live on a sphere, which means there’s always someone more west than you. And so we can’t blame the West, but we can look at the fact that there’s a worldview of Continentalism, which is predicated on extraction and away, go away, go west, go there, throw it away, get away.

When you’re on Island, you don’t operate that way. You don’t throw anything away, including people. We need everybody, and so we’ve developed processes and practices of restoring relationships when they break down. We don’t throw people out of the canoe.

That analogy that the island is a canoe and the canoe is an island, we need everybody in the canoe. All hands on deck. But now others want to drive the canoe. They want to take it to their destinations. And the risk of cultural appropriation is very big today. If there’s anything that we’re having to do as we restore our cultural practices and start sharing with our children is that you have others who are coming in and are accommodating themselves and everyone else all in the auspices of wanting to understand a relationship with Nature. Which is fine, I think we can welcome that, but not at the risk of that also being taken, the intellectual property, the cultural intellect. And I think that’s where we are. We’re really having to operate from a very cautionary note. We want to share, but at the same time, let us share; don’t come and take. And that’s what we see more and more of, people are coming and taking.

AL: We see the co-optation even in concepts like Aloha.

KR: That’s correct.

AL: You were teaching this week around the deeper esoteric understanding of Aloha, and that it’s become this degraded, degenerated reductionist concept that Hawaii Airlines uses when you enter the airport, right?

KR: Right.

AL: That’s the sort of risk writ large everywhere.

KR: Yes.

AL: Maybe you could share just Aloha as an example of the depth of this teaching versus the reductionism that is peddled as Hawaiian culture.

KR: Thank you. Yes, Aloha is a way of being. It’s a spirituality. It’s your relationship with the divine, which is in all things. But when you get into a commercialized space, Aloha now has become a bumper sticker. It’s more than a greeting, and yet that’s all it’s treated as. Aloha, how are you? But no commitment. When you’re speaking and living in Aloha, there’s a commitment, an accountability. The term itself, Aloha, when you break it down to its spiritual component, is acknowledging the life-giving breath, the spiritual essence that can only come from the divine, whatever you want to call it.

In our case, that is Akua, the grand creator. And from that grand creator comes life. In the word Aloha, the last phrase, Oha, that root word acknowledges the spiritual life that’s given to all of us. It’s in all of us. When I’m engaging with you, my statement of Aloha is a commitment statement to you that says, “I will not damage your air.” Damaging your air damages my air, and so my commitment to you is that we are going to work together, whether it’s three seconds, three minutes, or 300 years. It’s a statement of commitment. Now, if you can’t make that commitment, just say, “Hi.” That’s a greeting. There’s no commitment in saying “hi”. Aloha is a deep commitment to not only me and you, but my ancestors and to my descendants.

AL: And the ecology.

KR: And the ecology. And those are our ancestors. Those are all our relatives. We are not separate from them because every plant is a medicine, it’s a food. And when I’m out of alignment, I get realigned by consuming and relating once again to that food. Yes, Aloha is how we treat our places, is how we treat ourselves because we are of that place. And while I shared my name with you earlier, our identities relate to that.

If we subscribe to the idea that we are what we eat, then it’s important for me to consume the land, the water, and the air of those places. Today, much of our food, our nutrition comes from some place else. Some will say between 85% and 90%. If that’s the case, future generations will not be able to claim what our ancestors and perhaps I would even claim.

I Am Hawaii. I Am this place. And my name happens to be Kumu or Ramsay. My father is so-and-so, his father was so-and-so, but I Am this place. And I would think that many of our Indigenous and Native cousins feel the same way. They relate to the deer, the bear, the hawk, the crow. In our case, it’s the Kalo, the taro, and to the ‘aina.

I am Hawaii because I eat her and she eats me. The reciprocity agreement of Aloha is my breath that goes back to the land as I receive breath from it, which means that I am the product of all of my ancestors and they’re feeding the land coming to me now. And when I return to the land, my descendants shall benefit from that too, which means I have to be very mindful about what I’m putting into the land as much as what I’m taking out of the land. As one elder would say, to give back in full measure, not just what we want, not just what’s comfortable, but in full measure.

An example of that, for those that are measuring, is that we know that in our islands, the filtration system for water into our reservoirs, it takes nearly 20 plus years for water to percolate from the top of the mountain into the aquifer, or 25 depending on the height of the mountain. And we happen to live on high islands, by the way.

The water that I’m consuming may be piped into my kitchen, the convenience of that took 25 years to get through the pipe to come to me. If we start looking at things like true cost pricing, what’s the cost of restoring a 25-year percolation system while you’re increasing the demand by putting more people, whether they’re visitors or not, is that there’s less water falling on the ground, less percolating because we’ve created impermeable surfaces with concrete. We’re running all that water off into the ocean and we’re creating a greater demand for the aquifer. Well, all the children I talk to, it’s simple math. “Kumu, we’re in trouble.”

We’re not putting enough into the Earth for all of the demand that we have, just the natural demand. We’re not even talking industrial. We’re not talking visitors, tourism or militarism yet. If we just were in basic relationship with it, we’ve already created an imbalance.

To give back in full measure means, at the risk of oversimplifying this, that when rain falls, it does three things: one third evaporates, one third percolates, and the other one third runs. The part that percolates feeds those springs and water, rivers and streams. The ones that’s running are feeding the forest, feeding the land. That’s the surface water. And then the stuff that evaporates eventually goes back to the system and starts all over again. There’s three parts to that.

Now, when you and I drink water out of the aquifer, let’s just say it’s one glass, how do I give back in full measure? What would that be? One glass of water or three glasses of water? Because I’m only receiving one third of what actually fell to the ground. Now, again, that’s an oversimplification, but if you think about it from that standpoint, for every gallon that I’m taking out, I’ve got to be putting at least three gallons back in.

And my neighbor, my brother, the guy across the street who’s not doing it, I have responsibility to cover him too. That’s Aloha. To give back a full measure means that for every glass of water, for every leaf that I harvest, every fish that I catch that I’ve done something to restore, leave that whole so that none of us find ourselves in a hole later. That’s the difference. That’s Aloha. It’s recognizing that I am impacting it.

Everything I do to it I do to myself. And while I may find ways of avoiding the pain or the discomfort of that which I’ve created, I have a descendant who may not be able to. If I don’t think about us and we and just think about me, which is really the standard of thought, it seems, in the world.

AL: Indeed, that’s the cultural norm.

KR: That’s the cultural norm today. We’re rewarded for what we do for ourselves. You go to school, you get the A for your test, not for what you contributed to the community around you. When you become the CEO of a company, your salary reflects you and what you’ve done for the company, regardless of what everyone else has done to support you in your paycheck. That’s a me society versus a we society.

AL: And so what do you say to someone when they say, “Well, in a me society, what is the role of human agency? How would I give back three cups of water for the cup I drank when the structure of the system prevents me from: (A) seeing the consequence and, (B) doing anything outside the dominant structure of the life destroying system?

KR: This is where we get into this week that we’ve been together. It’s acknowledging that knowledge is moving faster than wisdom. If we rely on the contemporary knowledge bases, we are disconnected from the ancestral wisdoms of the particular places. I don’t think it’s an either/or as much as it’s an “and”.

How do we begin to bring those elders together? And an elder isn’t necessarily somebody that is of age, it’s the wisdom that is demonstrated through life experiences that are very authentic. They’ve eaten, they’ve planted, they’ve fished because they can speak to that relationship versus I read this and I’m making a reference to something I read that someone else said.

How many references am I really relying on? And that’s what I’m running into a lot. We have a lot of people who have letters behind their name because they happen to translate multiple books that they read and they’ve created a new theory, but they’ve never done it. There’s no practical knowledge. If my commitment to anyone is that I only speak from lived experiences and the lived experiences of those elders that took me and put me on their shoulders and said, “Tell me what’s out there. We got you covered here.” But they allowed me to see forward with a set of lenses that allowed us to bridge the past to the future.

We’re not going back anywhere; we’re bringing it forward. And I think that’s the opportunity. But we have to recognize that looking forward, we’re already looking through a set of lenses that have been polished and shaped by a colonized mind. And so the deep biases there when we see that the criteria of decision-making that we’re using to assess and to assert is already been infected by that bias, and so each of us needs to begin to challenge that bias. It’s not so much what I know, but what’s the wisdom that guides that knowledge into understanding? And that requires action, doing, not sitting and just observing. And we live in a very observing world. TikTok, everybody’s looking, watching, but are we really doing anything? I think that’s the opportunity is to create opportunities for the tactile, getting our hands in the mud, getting hands in the water.

AL: This is a good bridge to the core of the dialogue, which is around deschooling, deconditioning, decolonization. From the context of where you come from, from the understanding of Indigenous wisdom with very deep awareness of the meta-crisis, Hawaii is a very particular context in which to see that, and being in an island that understands consequence in an age that is consequence-blind, in a culture that’s consequence-blind. What would be your recommendation around de-conditioning practices, decolonization practice, deschooling practice or praxis with the theory and action coming together?

KR: Well, one, I think it’s an awareness. And I’ll say I may be aware, but I’m not immune. We have to heighten the awareness and then challenge the assumption. Simply because 100 people does it doesn’t necessarily make it right. This notion that the majority rules, well, the majority of thieves shouldn’t rule the legal system, and so we have to challenge that. And because two or three generations have now assimilated, that’s the new knowledge. We shouldn’t do that to ignore the wisdoms that were there before. I think what we need to do is look for and invite that and if anything test it, not just move on because that’s the way we’ve been doing things.

But I’ll be the first to say too that there are cultural practices that we put away because they were no longer relevant. What we have to guard against is that we don’t just have a blanket approach. That was an old custom; let’s bring it back. That’s not right either. We have to honor the fact that our ancestors had a way, had a method, had a process, and they said, “This is no longer good for us,” so they put that away, but they also did not leave a note that says, “Don’t open this box.”

And so we start with looking at our cousins in other parts of the world like in New Zealand, they’ve maintained certain practices which we no longer do, and now we’re admiring our cousins and we start restoring that practice in Hawaii, not recognizing the fact that our Kupuna in Hawaii said, “That’s a practice that no longer meets the values or the virtues that we want our children and our society to grow into.” We literally put that in the garbage pile.

But we know through anthropology and archeology that when someone has a degree, they assume the right to dig up your ancestors and they’ll go through your trash and say, “Look at all these.” And then they will assert a belief based on that trash, and they create a whole new way of being based on your trash. Well, my grandmother threw it away because it was no longer of great use. In fact, it was potentially dangerous. There were dis-eases, disconnections that came with the use of those particular practices.

AL: Can you give an example?

KR: Well, let’s just say there’s a food that we thought was really good for us, but that food started poisoning us because we didn’t have it in proper balance, so we say we no longer eat these foods. One, because of its source, so we put that away. But one day someone comes in, finds the bones of that fish, finds the bones of that animal and say, “Oh, we ate this, so we’re going to restore that.” In fact, we’re doing that now. I think they just restored these ancient wolves that we haven’t seen in generations in the world. What are we really bringing back? The Jurassic Park syndrome.

I think we do that with cultures too. There’s certain concepts, spiritual practices that are part of a larger system. I open it and I close it. There’s salt, there’s pepper, there’s sweet, there’s sour, and there’s a balance. Well, when you get rid of the balancing factor and you just introduce the other, this is when you have a situation of invasive species coming in because there’s no predators, there’s nothing to stop that. Well, I’d suggest that some of the Continental thinking is as much a predator or an invasive way of being that has no balancing factor.

So in the absence of that balance, we now create an imbalance in the societal experience, the way you think, the way I feel. And all of a sudden we are now accommodating that because we don’t have the cultural or the spiritual balancing factor. Natural time, spiritual time, but we’re operating in artificial time and we don’t know how to be in a natural space anymore.

We don’t know how to deal with the spiritual spaces because so much of we do is in the artificial space to the extent that I could be out here chanting into the forest and it’s responding to me, but a person who has never experienced that won’t see it, won’t feel it or hear it, and they’ll be confused by that. “What are these people doing?” But a few minutes later, they have no problem picking up the cell phone and saying, “Siri, what time is it? When’s my next appointment? Show me the directions from here to there.” They have full confidence in artificial intelligence while we, the Native people, have full confidence in our relationship with natural and spiritual intelligence. That’s the gap.

AL: Thank you for sharing.

KR: I don’t know if that makes any sense.

AL: No, it does. And maybe we can dig one layer deeper.

KR: Sure.

AL: Specifically, what are the thought-forms of capitalist modernity that need to be deconstructed and de-conditioned in order for us to return to right relation?

KR: Well, I think the largest thing that’s looming over us all is this concept of accounting versus accountability. We have leaned into this idea of red and black, supply and demand. Education itself is more supply side than is demand side. We’re putting all these people out with degrees or with knowledge, but we haven’t maintained the proper demand side, so now we have people floating around with degrees and knowledge, with nowhere to put it, and we’ve created a lost society of people. And/or we bring people from elsewhere thinking that what they know is better than what we know because somehow we’ve given that greater value.

The real question is who are we accountable to? And that challenges what I would say the metric of success. If there’s anything that the commercial or the capitalist mindset is, is that we’ve established a metric of success that is based on quantification; how much rather than how well. It doesn’t matter how much I gather today if it left an entire community hungry. It doesn’t matter how much I built if the entire community is houseless. If the metric of success is “see what I did and what I built”, while the community I’m in isn’t benefiting from it, my accounting side’s working, but my accountability side is completely off.

Then we begin to pat ourselves on that because we can reference this, but we have no reverence for that. You have this juxtaposition between reference and reverence; accountability, and accounting. And I think we have really fallen into accounting heavily because we don’t have the qualifiers versus the quantifiers in any of our metrics. You don’t see a line on there, “Aloha. How many people were fed today?” That’s not on the metrics.

Imagine if our question and our inquiry at the end of the day in a business wasn’t how many homes did we sell today? Or how many units of X, Y, Z did I sell? But ask, “Are the children fed? Did everyone eat today? Is everyone housed? Are the parents capable of caring and feeding for their children?” Because if the answer is yes, then it would suggest that perhaps we adopted principles and practices that feed, house, and heal.

But what is a medical industry business making billions of dollars while you have millions of people dying from illness and disease that has been completely disconnected from the business of health rather than the act of health? That’s what I mean. We’ve allowed accounting to override the accountability of the people. How much has become the priority versus how well. And I think when we go back to Native communities that live that way, I think we restore that balance.

AL: And there’s implications for everything in what you’ve just shared, right? From private property to what is leadership.

KR: Exactly.

AL: Maybe you could say something about each private property and leadership.

KR: Sure.

AL: You teach at a leadership institute.

KR: That’s right. And the leadership there, is it Wall Street leadership or is it Main Street leadership? Leadership in the home versus leadership at the Capital? Leadership is the head. Well, in contemporary leadership models, we cut the head off and we remove the head and we put it someplace else, and then it sends its thoughts back, but it doesn’t really participate. We have headless societies when we operate from the Wall Street model, the constitutional. Not the Constitutional, but the Congressional leaders. We actually go in and remove leadership from the home where it really belongs.

For me, the Pacific Island Leadership Institute is really exploring how do we put leadership back in communities? Because when we remove them, the community is running around in the absence of that and waiting for permission to act rather than taking the leadership to act. Leadership is not a position, it’s a way of being. I can follow my father, I can follow my mother. Grandfather has done this, the tradition of him doing this, that’s what I’m following.

But we’ve disconnected that and we’ve presumed that the representative I’m electing to represent me in that office also leads me. How did that happen? They weren’t trained in leadership, they just happened to evolve into a position that we have now called the leadership position, when in actuality their role and responsibility is to represent me. I have to participate in that leadership. I need to participate in sharing with them what our needs, what my desires and my thoughts are, and the current leadership practices don’t do that, right?

And so for me, the Pacific Island Leadership Institute is what is the world view of an island? But dealing with the impact of a Continental worldview. In Nature, it’d be like taking a coconut and shoving the seed into the space of an avocado. They both have seeds. That’s their similarities. That’s it. We’re taking Continental thinking and mind and development and shoving all of that into an island. Something’s going to break. It’s just inconsistent.

So when we see operations on an island like Oahu, where I’m from, where you have a continental practice, let’s call it Costco, the largest producing revenue maker for this company is located in Honolulu. Now we have 1.2 million de facto population, maybe 10 million people visit per year, yet that one store produces more revenue per day per square foot than all stores across the country. How is that possible?

Either we’re consuming more than everybody else, which I think from a dynamic standpoint is difficult to do, I don’t know that I can eat more than you to achieve those kinds of numbers, or I’m paying more than you for the same amount of value or volume, if you would. Something’s off. How can an entire country be producing less than a little island in the middle of the sea? There’s an imbalance happening.

And it’s not necessarily a conflict of values either. I think it’s a conflict of priorities. And I think is Native people and communities, we have to start questioning that. Whose priorities am I living, the priority of the developer, the priority of the government, or the priority of the community, and more importantly, the priority of the land?

AL: Which leads us to private property.

KR: Private property. The distinction of property itself suggests ownership. That’s really a foreign concept to Native minds, Native people, especially if you start out with a simple concept, I belong to it. How can it belong to me? That’s like buying your mother. And for us Native people, that’s what it is. That’s Mother.

AL: How can you own something you belong to?

KR: How can you own something you belong to? How can I own that? That’s my mother. We’re having this conversation with sea level rise. I’m in a conference with these people, and the entire time, two days of conference, the conversation was about insurance, about rebuilding, development programs, etc. On how to deal with the impacts, the damage, etc. Not once in the entire conversation did they actually talk about the ocean.

I’m the last person on the last panel, the last speaker. If I was going to take a shot, that was it. My question to the group was simple this: “Show me your hands of how many of you have a relationship with your mothers.” And you could see this. This is where you throw the disruption in. This is the hacking. And at that point, a few hands went up. And then my next question was, “How many of you have a relationship with your grandmothers?” A few more hands went up. And I said, “If you’re wondering why, is because my question then is if you knew your grandmother was coming home to live with you, if you got a note that mom’s coming home, is your instinct to build a wall to keep her out or to create accommodations to bring her in?”

This conversation about sea level rise – mother’s coming home – grandmother ocean is coming home – and we’re sitting here trying to figure how to keep her out. Now, that is nuts when you think about when you’re on an island and you’re in the ocean, not on it. And to spend time and energy trying to keep it out while you’re in it is ludicrous. See, that’s a relational question. The conversation they were having was a transactional question.

The real deal is what’s my relationship with you? Rather than what’s a transaction that I can benefit from? And it doesn’t even have to be a shared benefit as long as I get what I want from this thing. Well, mother’s coming home and I don’t know that there’s any transaction that’s going to override that force. She’s been kind to us up to now. She’s been very patient. But she says, “I’m coming home. I’m not feeling well, and it’s time you go to your room. It’s time for you to figure this out.”

But this is where the Western, or I’d say the Continental mindset, really the concept of mind over matter, that I can outthink this, that I can intellectualize my way through this. And property ownership is one of those things.

Under property ownership, in the bundle of sticks of ownership includes the right to destroy that thing. We’re now changing the environmental protection rules in order to allow people that right to destroy that thing. And if I can do that, I separate you from your gathering rights, your Indigenous rights to this land, to this space. I’ll acknowledge that. Great. You can have at it, but I’m cutting every single tree down because I can because I own it. That’s the difference.

And we use the term stewardship, but oftentimes some of us still operate as owners under that stewardship model. But we’re really talking about kinship. What’s my kinship with it? And what I own in that kinship is the stewardship responsibility to care for it; for it as well as everyone and everything that relates to that, the interdependence part of that, which is difficult when there are some of us who still feel there’s an independence that we need to establish. But the reality is there’s very few things, if anything in the world today that is truly independent. Everything’s interdependent. The whales rely on us to keep the ocean clean. The whales rely on the water to be there. These are the largest creatures on the planet, perhaps the greatest wisdom keepers are, they’re not independent, they’re interdependent to the smallest creature in the planet, the plankton.

Here we are, these two-leggeds walking around the world thinking that we have some kind of power over all of that. Then I think that’s the difference between ignorance and arrogance, some of us just don’t know. And we might be able to forgive ignorance because you didn’t know, but now that you know, don’t turn a blind eye because that’s arrogance. Now you’re just ignoring me, and that’s what makes us ignorant. And unfortunately, I think there are many who have chosen to be ignorant. It’s easier, it’s more convenient. That’s the opportunity is how to begin to create and recognize that very conveniences that we’ve become accustomed to are really the source of our problems because we’re no longer in proper relationship.

AL: Can you share a little bit about your vision for Hawaii?

KR:

Yes. This idea stems from the concept that Hawaii is in the middle of what I would refer to as the Blue Continent. Now, that may sound odd since I’m suggesting that there is a difference between Continental thinking and Island thinking, but by referring to the Pacific, the largest single body on the planet, all continents fit into that, all land fits in that ocean, it’s really speaking to the Continental thinker and adjusting the metric, the economy of scale.

The islands in the Pacific such as Hawaii, Samoa, Micronesia, we may appear to be separated by ocean, but in the Pacific, we’re connected by that water. If we reframe the blue continent, Pacific as a blue continent, then all the energy is coming into that continent. US called it the Indo-Pacific. Hawaii is in the middle of that.

The practices that we are experiencing now are producing war. Whether I’m at war with nature or war with my neighbor, country versus country, a lot of that energy is now on the borders and the outskirts of this blue continent while in the European continent where supposedly all of this originated, this tension that we have with capitalism and financial gain, et cetera, et cetera, when you have the World Economic Forum on that side of the world making decisions for us on this side of the world, that’s a huge disconnect. How can someone who lives on the fringe of the ocean make a decision for someone that’s in the ocean?

If the world has been operating off of what it defines as peace from a place called Switzerland, Geneva where the United Nations may be, and yet the tensions are all the way across the other side of it, wouldn’t it make sense that that conversation take place in that arena, or as they say in that theater? If the Indo-Pacific theater includes Russia, China, the United States, all of South America, Australia, and Antarctica, that’s 23 to 26 different emerging economies all looking at the same pond. Wouldn’t it make sense the the conversation of peace, health, prosperity would take place in the center of that rather than the fringe of an old economy, but the center of the new one?

If there’s any logic to that, then I say what’s in the center? And what has the greatest capacity to reach the most number of people? Just from a geophysical standpoint, if I drop the stone in the ocean where Hawaii is, that ripple affects everything around it. Let’s say that ripple is a message of peace, that ripple is a message of harmony, that message is a ripple of health, then it would make sense that this embodiment of peace that we call Geneva or Switzerland could easily be done perhaps better in the Pacific where all the action is happening.

The proposition is for the Hawaiian Kingdom where Aloha was their guiding currency, the currency of exchange was Aloha, that spirit. Imagine if the conversation was, “Come here and let’s resonate from here.” And so the idea is to have a peace institute, not just a global or planetary, but one that begins to go intergalactic because we’re affecting the universe around us as well as the interdimensional because we are beginning to shift our dimensional existence, the existential acknowledgement that it’s not just us.

So the proposition is to establish such a center in the Pacific and invite those who would attack us to actually center themselves there in this place as peace. And I don’t think there’s any question in most people’s mind that know anything about Hawaii that that’s an opportune place to have this conversation. I would welcome anyone to ally with us in bringing about that vision. Leave your guns at the door. You come here and this is about perpetuating a future of peace, harmony, health, prosperity at multiple levels and not just in the physical plane.

To really begin to shift the conversation from a shift of physics into a place of spirit, because I think it starts there. And understand that the insanity of it is to keep doing what we’ve been doing and expect different results. And many scholars have shared that thought numerous times. I think that’s what that is. We need to think and behave in a new way and perhaps even in a new place, which ironically is the old place.

AL: Thank you for sharing. You said this beautiful prayer, and I think of it almost as a prayer for the oppressor where you said, “May they feel they have enough.”

KR: Yes.

AL: Which is addressing the scarcity of the Continental mindset that drives the separation, the colonialism, the imperialism, the militarism, etc.. And so perhaps you can close with a prayer for us.

KR: Sure. That is the prayer. I think the prayer is one that acknowledges that we have created a competitive nature. That is not our nature, and therefore there’s always a sense of scarcity and fear. The prayer is that we will reconnect with Source. And that internal source, that internal compass allows us to navigate our places, our relationships, knowing that whatever we need can be presented, that we can access that because we now have a relationship with Source.

The paradigm of fear and scarcity is inconsistent with communities that lived in abundance and sustainability. Two different worlds. And so many of us are continuing and trying to bring that forward. The prayer would be that we are not doing that with that previous metric of fear and scarcity. The prayer is that we all adopt and live, be Aloha, as our Queen stated in her definition of Aloha, one of the definitions, she said Aloha is to see without looking, to feel without touching, to hear without listening. But above all is to know the unknowable, the mystery, the awe, the wonder.

What she was saying to know the unknowable really is to know the Source, to know that which all things come from. And if you know that, then whatever you need to know, whatever needs to be provided to you can be given because you know you can ask. You have a relationship with the creative nature that provide us with everything we need.

That’s the prayer, and the prayer that each of us will have enough, and that those families and communities that are experiencing the tensions in their lives because we didn’t learn that. I need more. And as a result of me getting more, they have less. To establish and pray for equilibrium, not equality, but equilibrium that brings about balance.

That would be the prayer; that everyone finds a balance, and more so that each of us who will be in the right place for our good and for the good of others, because I believe all things are for the good. But it’s a perspective, it’s a point-of-view, and it requires us to be concerned about others as much as we are of ourselves. That’s the prayer is that we can find the humility to recognize the brilliance in others, thus demonstrating our own. This is Aloha.

AL: Thank you, Kumu. It’s an honor to have you. And thank you for being a living prayer of your ancestors.

KR: Thank you for having me. And my ancestors thank you and your ancestors. Aloha.

About:

Kumu Ramsay Taum is recognized locally, nationally and internationally for transformational leadership in sustainability, cultural, and place based values integration into contemporary business models. He graduated from The Kamehameha Schools, attended the United States Air Force Academy at Colorado Springs, and earned a B.S. degree in Public Administration from the University of Southern California.

Kumu is a recognized cultural resource, sought after keynote speaker, lecturer, trainer and facilitator and is mentored & trained by respected kūpuna (elders). He is a practitioner & instructor of several Native Hawaiian practices: hoʻoponopono (stress release and mediation), lomi haha (body alignment) and Kaihewalu Lua (Hawaiian combat/battle art).