This dialogue with Dr. Jessica Hutchings explores the grief and resilience of Māori communities amid renewed assaults on language, culture, and land under a far-right government. Hutchings weaves insights from her dual activist heritage—Māori sovereignty and Gandhian resistance—with a call to remember ourselves as nature-beings. She shares Māori cosmology as a pathway to healing and warns against the commodification of Indigenous wisdom.

DESCHOOLING DIALOGUES

Episode 9 – Alnoor Ladha with Dr. Jessica Hutchings

This dialogue took place in December 2023 at Mangaroa Farms in Aotearoa (New Zealand) as part of a Biome Trust gathering.

Alnoor Ladha (AL) | Welcome to the Deschooling Dialogues. This podcast is a co-creation between Culture Hack Labs and Kosmos Journal. Culture Hack Labs is a not-for-profit advisory that works with social movements. You can find out more@culturehack.io. Kosmos Journal is a cultural-spiritual journal that you can find out more about at kosmosjournal.org. This podcast is brought to you by the dedicated viewers and supporters of Kosmos.

I also want to thank our production team of Jeff Kulig and David Frank, who are supporting us as part of the Ma Earth team. I also want to thank Biome Trust and these lands of Mangaroa Farms. We’re sitting here today in Aotearoa, also known as New Zealand.

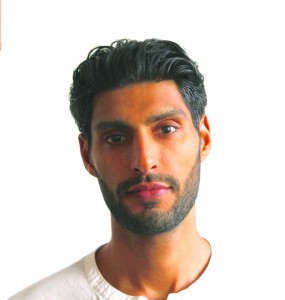

We’re here with Dr. Jessica Hutchings. It’s an honor to be with you. Thank you for joining us.

Jessica Hutchings (JH) | My honor, kia ora.

AL | For the audience: Dr. Jessica Hutchings is a Māori activist who works on food sovereignty, land rights, and Indigenous rights. Jessica comes from the Ngāi Tahu tribe on her father’s side, and on her mother’s side she is Gujarati, which we share in common — and comes from the lens of Gandhiji and the salt marches in the Dandi Beach region. Extraordinary to have these two powerful resistance lineages and activist lineages in one incarnation. And so by way of intro, I think we’ll just start with the context lines and maybe a little bit about your story if you want to weave it in.

JH | Kia Ora. Thank you, and thank you very much for talking with me today. I think you’re right — I think it’s about these two activist lineages coming together in the different sides of what we call our whakapapa, or from my culture in Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview), what we refer to as our genealogy or our lineage.

On my Māori side, we’ve been fighting against colonial forces for many generations. My tipuna (ancestors) have been fighting, and we continue to do that right now in the present day — even more now, with a swing to a far-right government here.

On my Indian side, my grandfather was a freedom fighter, and with many of the men in our ra — the villages, in the village where I came from — there was no choice but to go and walk with Gandhiji, as our lands were being encroached by the British.

So it’s British colonization on both sides of my whakapapa

And it’s no wonder that I’m an activist. I have a deep, deep calling for Earth justice, for Earth democracy, for returning back to being nature-beings, for calling out injustice when we see it.

So it’s always been the work that I’ve been doing, and I’m now, I suppose, at a point in my life where I can take off some of the cloaks that society have put on me or that I chose as well in my career to do. I ascribed a persona of an academic and did PhD studies and postdoctoral studies and Indigenous health and in environmental studies. But actually it’s just time now in my fifties to start to pull all of those cloaks off to realize the more I know, the less I know and to become more humbled in that place of being, in nature being. So I think that’s where the activist work and the activist lineage is taking me now.

AL | Yes, indeed. Colonialism for all its shadows is also what redefines purpose in some ways. When you’ve incarnated into lineages such as yours, purpose becomes clear.

I also have British colonial rule on all four sides, Persian, Arab, Indian, East African. But the context of this island is very particular, right? Because colonialism, settler colonialism, started in earnest officially in the 1840s, which is very recent. The British had 350 years to perfect “divide and rule” and “define and rule”. Perhaps you could share a little bit about the context of colonialism on this island and its effects on Maori peoples and the ecology here.

JH | Thank you for that question because it really sets the context for the conversation that we are going to have because right now, today, it is ever present in our everyday reality as Indigenous peoples. We’ve just had a far right government sworn into New Zealand, and supposedly they’re going to be in power for three years. So we are at this stage now where everything is being pulled back. Our language is now being stripped out of our government agencies. And this was only announced last week.

AL | They have only been in power for two weeks.

JH | They’ve only been in power, I think they were only formed, as government, last week.

AL | So it was their first act to come after Māori culture.

JH | Yeah, it’s their first act to come after Māori culture. We could have an intellectual conversation about it. You and I have both in our lineages have experienced British rule, but as a human being, as an Earth being, that’s embedded in my culture and my language and my relationships with Nature, I’m just weeping. I’m just weeping. And my friends and my family, we are weeping for it because it’s not about rights. It’s not that we don’t have the right to our language that we have a right to speak it. Sure we do, but it’s actually, it’s the essence of who we are, and it’s the language that speaks to the land in this country. So my ancestors fought for our language to, again, have visibility in Aotearoa, and I can’t believe that we’re at this stage where now it’s being pulled back and they are saying that Indigenous languages in New Zealand are not relevant.

JH | Yeah, it’s their first act to come after Māori culture. We could have an intellectual conversation about it. You and I have both in our lineages have experienced British rule, but as a human being, as an Earth being, that’s embedded in my culture and my language and my relationships with Nature, I’m just weeping. I’m just weeping. And my friends and my family, we are weeping for it because it’s not about rights. It’s not that we don’t have the right to our language that we have a right to speak it. Sure we do, but it’s actually, it’s the essence of who we are, and it’s the language that speaks to the land in this country. So my ancestors fought for our language to, again, have visibility in Aotearoa, and I can’t believe that we’re at this stage where now it’s being pulled back and they are saying that Indigenous languages in New Zealand are not relevant.

We all need to speak English. Everybody understands English. Let’s have all the signage in English around government departments and government services. For many of us, myself included, this is one of the cloaks that I would like to have thought that I’ve de-cloaked, but here I am putting it back on right now.

So I’m really conscious of that as well. But a lot of our work has been in working for these very incremental wins and little changes, and there’s something to be said when these small wins get pulled apart, it makes me think about the resistance work and the activist work that we do when we are only making these incremental shifts, what’s the bigger shift, actually that we need to make?

And so as we weep, I, we connect back to Papatūānuku, our Earth Mother, back to our deities of Nature and find our solace back in our cultural paradigms again.

AL | We are seeing this everywhere across the world, right?

It is the consequences of the Western, materialist, separatist, rationalist, capitalist culture breaking down; it is the fulcrum in many ways, of late-stage capitalism. What we’re also seeing is the transference of the blame back onto immigrants, onto Indigenous peoples, onto the so-called “Other” without taking any real responsibility. And it’s another way to hold on to the existing structures.

People want to talk about colonialism as if it’s some historical event, but it’s ongoing coloniality. There’s an ongoing capitalist colonialist reality, and the descendants of the colonialist settlers here, and almost everywhere in the world, are now voting in far right governments and extremist governments, and fascist authoritarian governments, as a way to cope with the changes that have been brought by the very system they created in the first place.

And so we are at this very strange moment historically, where instead of reckoning or reconciliation or rematriation of land or the things that the majority world is demanding, we’re actually seeing a renaissance of statist, fascist, xenophobic, racist policies the world over. And it’s probably going to increase as climate change and inequality and the other consequences, the logical outcomes of neoliberal state policies, play themselves out. And it’s happening in a very particular way here.

To go after culture first, to go after Māori language first. And social change is also operating within the existing paradigm. It’s sanctioned activism, sanctioned by big philanthropy, by big government, by grants, by the remit you’re allowed to operate in. How does this play out here on a day-to-day level?

JH | I always talk about ongoing settler colonialism in New Zealand. And so colonization isn’t just something that happened in 1840 when the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between Indigenous peoples, between Māori tribes, who in 1840 within these documents that were signed, identified or claimed that space as independent sovereign nations. One of the impacts of colonization in Aotearoa has been that it has grouped Māori tribes together as one homogenous group, but actually we are independent sovereign nations, and we were always that pre-colonization. So even the way that the crown or the colonist refers to or sees Māori is incorrect in terms of how we structure ourselves tribally as a people.

We are an easy target. We always have been in politics, the marginalized, the queer folks, those of us that are queer, those of us that live on the margins, live in those liminal spaces. We’re always the ones that are easy fodder for the politicians. And we’ve just suffered two months of electioneering with a whole lot of race baiting. Now we have a government that’s come in and the race baiting is still going on with what I would describe as a legislative assault writ large right across our legislative framework in New Zealand to remove every clause that gives rights to the Māori and that recognizes and uplifts the Treaty of Waitangi.

So the Treaty of Waitangi, is the founding document of Aotearoa. It is the document that the British signed with the leaders of our tribes at the time in 1840. And it guarantees to Maori our sovereign rights. What it gives to the British is it gives them the right to govern, but that doesn’t supersede our right to sovereignty. It also provides our people is full undisturbed protection of our lands, forest, fisheries, waters, and other taonga. And taonga refers to treasures. So that’s things like language.

That’s the intangible.That’s our soils, that’s Papa, that’s our Earth Mother. All of our deity landscapes as well are protected. One of the things that people think about when they think about New Zealand is, oh, clean and green. A lot of people want to come to New Zealand because it’s clean and green. Well, that’s a myth.

We have some of the worst pollution in the world in our waterways. We have some of the highest rates of biodiversity loss anywhere in the world. We are not a clean and green nation by any means. But what that has meant for my people is that it’s meant that we have been excluded from being able to eat our cultural landscapes. And so with biodiversity loss, we have the loss of our traditional food sources.

And so the impact for us of colonization has been to dismantle everything, which is what the colonizer does. Dismantle your language, dismantle your cultural practices. We will exclude you from the remaining remnants of wild areas that are left. And we will establish those as conservation areas that we know come from a history of white supremacy, of excluding and locking out Indigenous or native peoples from their lands.

So our experience of colonization is very similar to the experience of many other Indigenous peoples all over the world. But what I often hear when I travel is that, oh, Maori, you’ve got it good. Oh, it’s not so bad for Maori colonization. And I hear this from predominantly non-Indigenous people when I travel, it’s almost kind of like the, oh, you are the good Indigenous ones. I mean, oh, you’re the good brown person in the room.

Actually every aspect of our culture has been assaulted.

I think it’s really easy to see that colonization still exists in right now at this moment because when we see our culture dismantled and pulled apart and then put back together and then reinterpreted and fed back to us, and we are told that this is actually what Maori means and this is the value that we are going to place on it, that’s what colonization is. When someone takes your culture and pulls it apart, puts it back together and then feeds it back to you, or actually in most cases totally dismantles it, so you cannot recognize it to be able to put it back together.

So we are back to the barricades here, which might be for many of your listeners after the two terms of Jacinda Ardern as our Prime Minister with a big open heart and love for people that we have actually now swung really hard to the right, and that’s really concerning for Māori communities.

The day the government got sworn in at the beginning of this week, there was a national day of action called for anybody in New Zealand. We went to the protest on Monday and marched down to our parliament with hundreds and hundreds of people, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. That happened all around the country. So that’s heartening, but it’s also a real ache that we’ve been marching on the streets for generations and we’re still doing it.

AL | Yes, it’s a devastating context. And this idea that we can do some kind of oppression hierarchy who’s received the worst end of colonialism, is itself such a colonialist construct of competition and ranking.

You said something very beautiful about finding solace in the Earth that you coexist with. Maybe you could say a little bit about Māori cosmology in this context.

JH | I love the phrase of one of our Māori elders, Māori Marsden, who talks about our worldview as this interwoven Māori universe. And when I think of a universe, I’m outside of this planet, I’m out in the cosmos then, and everything is interwoven and everything is interconnected, and I think about the microbes in the soil, and then I think about the whetu or the stars in the sky and the correlation between stars and soil biodynamic practitioners.

I stir a lot of cow poo and sometimes, and then apply that Preparation 500 [a Biodynamic preparation] onto our land, onto our property. But that’s all about making those connections between the soil and the stars. And that’s what the interconnected Māori woven universes are like many other Indigenous cultures started in the void of nothingness. And then from that void of nothingness came the first sounds. And it’s from those first sounds that then we have the beginnings of creation.

There’s a beautiful prayer, and that prayer/incantation talks about the beginning of our world, starting from Te Kore, from the great nothingness, and then it follows all of the different realms through, coming right through to our Earth Mother, Papatūānuku, to our Sky Father, Ranginui. And then it’s from those beings, from those divine beings, that us as humans, Tangata, that humans came forth and emerged into the world.

So that cosmology, the Atua line or the deity line, stretches in cosmological time. I don’t even want to describe what it is; but it’s a realm of time that’s immense. And then we think of the human period of time, which is just a little drop. And so we have to connect back. That’s who we are. We only know ourselves as Indigenous peoples through coming to know ourselves through our Atua, because we all embody — we all embody the essence and the characteristics of all of our gods, of all of our Atua, of all of the shape-shifting that Tāne did, of the earthly grounding that Papatūānuku, our Earth Mother, can give us, of the calm that Hineahuone, who’s the deity of our soils, of what she can provide.

We can feel the Ihi or the anger or the breeze of Tāwhirimātea. So Ihi is the seat of our emotions. And we’ve lost that. We’ve lost that — not just as human beings, but as Indigenous peoples especially. We live in a settler-colonial reality. So we don’t talk about ourselves as the manifestation of the realms of the Atua, but actually when we are feeling Riri, when we are feeling angry, or when we are feeling a bit unsettled, we might know it as Haeana or something else, but actually that’s the deity of the wind coming through me. So that gives me an opportunity to connect to those Atua landscapes.

And so knowing ourselves as divine — being as a divine being and in relationship with the divinity of nature — is what the Māori worldview is all about.

AL | It strikes me three aspects that are quite common, interwoven through mystical traditions, Indigenous traditions, and wisdom cultures; those worthy of the word “culture” is that there’s an embeddedness. You’re embedded in something bigger than yourself as opposed to the atomization of Western culture. There is an entanglement, a deep understanding of entanglement at a quantum level, at a biome level, at an ecological level, at a relational level.

AL | It strikes me three aspects that are quite common, interwoven through mystical traditions, Indigenous traditions, and wisdom cultures; those worthy of the word “culture” is that there’s an embeddedness. You’re embedded in something bigger than yourself as opposed to the atomization of Western culture. There is an entanglement, a deep understanding of entanglement at a quantum level, at a biome level, at an ecological level, at a relational level.

And then there’s entrustment, there’s responsibility that comes with these endowments, whereas western culture can be characterized as “entitlement” culture. Literally the entire Western legal system is based on the notion of private property title. Entitlement is so deep in the core of Occidental mindset and with colonization, there was an exportation of that entitlement all around the world. And we’re seeing the effects of that play out everywhere we look, even in the healing cultures, people feel entitled to their trauma in the West. There’s nothing we’re not entitled to. There’s a homelessness in this.

And as you were talking about the deities of these lands, that deities and gods were always “of place” because they lived on the same realm. That’s how we interacted. That’s where we learned from. And as soon as you have the universalization and the colonization of Christianity where there’s now a God nowhere, somewhere up there, which is universal and imposed, it becomes the God of homeless people. And so homeless people, what Steven Jenkinson would call “spiritual orphans”, bring their homeless God, the God of nowhere. And there’s this deep disconnection even in the deepest aspects of spirituality within the God of Christianity being distant and Other, and it plays itself out in the colonialist capitalist landscape.

JH | We have a phrase in our language where when we stand in our tribal meeting houses and we greet the Earth Mother, we would say, I greet the Earth Mother outside. I also too am an embodiment of the Earth Mother.

I am a gardener and I spend a lot of time with my hands in the soil, and I am the embodiment of our soil deity without a doubt. That’s who I am in a relationship with for most of my week actually. That’s who I tend to and nurture for most of the week. All of the other deities are racing around, and the wind and the rain comes and this, that and the other, and we have a reverence for them. But I really feel that connection with Hineahuone.

AL | Mircea Eliade, one of the great comparative religion scholars from the 1920s and 1930s in the US wrote many beautiful books. One of his ideas and theories from comparative religion, studying mystical traditions, Indigenous traditions, Tibetan Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, was that what mystical traditions and Indigenous traditions share are two things. One is the understanding of reincarnation, and the other, is embodiment.

So let’s take Norse culture. A Norse fishermen in the fjords somewhere is not praying to Thor when they’re fishing. They embody Thor in order to complete their task. That was the role of the gods to serve as an archetype to embody, to become.

And there was also a deep understanding that there was a karmic cycle and time was cyclical, and he would come back. And what we see with the Abrahamic traditions is this cutoff from the idea of reincarnation, right? Only Christ is the final resurrection. We’re waiting for the second coming, we go to heaven or hell. There’s an imposed binary and finality in that.

The point of God [in Abrahamic traditions] is to pray to God, to ask for your needs or to go through the mediation of a pope or a pastor or what have you, to pray for you, to pay for forgiveness through indulgences or what have you.

There’s a disconnection when these two aspects are missing, when the idea of cyclical time and reincarnation, and the idea that we are fractal aspects of the divine, embodying aspects of the divine, are lost. When we lose those two things, we have what we have now, which is a culture of monotheism, monoculture of the mind, monotony, etc.

JH | In our Māori culture, we don’t have a philosophy of reincarnation, which is really interesting. But then of course on my Indian side, it’s a very different story. When our people die in Māori culture, they move up to the realms of the stars. That’s where they move to. And so we have a time of releasing our dead, those that have passed away, and we call that time Matariki, which signifies a new year.

Yes, we can describe it as Māori New Year, our ancestors never went, oh, it’s Māori New Year. It was a time to farewell the dead, connect with the seasons. It was a significant moment. And it’s the time of the rising of the star cluster that you may know as Pleides. It’s known by lots of different names around the world. When that star cluster rises, then the Waka, which carries our recent dead, moves to the other realms.

AL | And it’s cyclical and it’s embedded in this reality, right? There is not some absent God in the universe, it’s a star system that is in relationality with Gaia herself.

JH | All the time. Yes, all the time. And it’s also too, part of that ceremony, all of the stars in that cluster have a relationship to food. So it’s not just about farewelling those that have passed on, but it’s also about making offerings to the star cluster and to the deities residing in that star cluster to ensure bountiful harvest for the next season that’s coming.

AL | This is the cyclical nature of the dead feeding the living and the living feeding the dead. That’s so embedded in wisdom traditions and we can see the implications of a death-phobic culture of the West, where the Silicon Valley set are trying to upload consciousness to the cloud and find their immortality and live forever, not because of a love of life, but because of a fear of death.

JH | We have a practice in Māori culture of a period of mourning or a funeral process called a Tangi or a Tangihanga, which is to cry. We go into this period for about three days. So we are with the body on the Marae which is our traditional meeting house. It’s an open space so anybody can come in and the body lies in state, and we sleep and we lie with the body and we touch it and we grieve with the body.

Some of us have had the privilege of growing up with these traditions of Māori culture, and while we have everyday settler colonialism happening in New Zealand, we are experienced in death and dying from a very young age because we’ve slept next to our loved ones as they begin their journey up to the stars. So it’s not anything to fear, actually. It is part of our culture. It just seems abnormal to think that it’s not part of a culture, but it’s part of a culture.

AL | This is probably a good transition to what we need to deschool and unlearn as the dominant culture, as part the master narrative. And we’ve touched on a few things with food, ecology, cyclical nature, embodiment, death and dying. But how would you phrase your counsel to the young and immature culture of the West with its childish claims on life and reality?

JH | I would say we need to unschool and unlearn ourselves as being humans because that’s an ascribed term. It’s a cloak. Then we ascribe some meaning to that. And then from that comes a set of behaviors that we display. We need to take that cloak off and we need to learn to cloak as nature beings again. We need to remember our place in the ecology of the world, in relationship to our deities and in relationship to nature.

There is no separation and no hierarchy in any of the cultures that I come from or that we come from in terms of humans over Nature. I mean, this is a false binary that has been imposed on us through Renaissance thinking right through to colonization.

So what I would say to the young people of the West, is to remember yourself as nature-beings and to not try and find it through the head space, but to find it through the heart space or as we refer to in our Māori culture as the liver, these organs in our body that are just as powerful and just as important for opening up light and opening up spaces for transformational change.

So come to know yourself again. And I think the way to do that is to be still and to be silent and to be with, and to not be dominant, and to not be over the top, but actually just to learn to be with and to breathe with Nature. We don’t need to do anything. We don’t need to be anything. We’re not asking anything from Her.

We’re just being, we’ve done so much harm, as we know, to Nature. I mean, and this is again, it’s the weeping inside, it’s stronger and stronger every year. We really feel it, especially in our country that our rivers and our other lifeblood of our land, and they’re the veins of our Earth Mother, of Papa and Rangi, and they’re being polluted by dairying, by fertilizers, by chemicals, by really poor land management practices. We have to come and know ourselves as nature-beings again and find that connection back in that’s so deeply important for Indigenous peoples listening.

What I’d say is that we need to come back and know ourselves again as Indigenous peoples. And so this is a lifelong journey for those of us that live in settler-colonial nations because everywhere around us is dominant white culture, everywhere around us, hetero-normative, white, patriarchal culture is everywhere.

And so how then for myself, as a queer Indigenous woman, how then do we come and know ourselves when it’s not reflected in society? So for Indigenous peoples listening, one of the things that the colonizers did was they took away our dignity as Indigenous peoples to know ourselves as indigenous. Our language wasn’t good enough, our culture wasn’t good enough, our food sources weren’t good enough. And so all of that was dismantled and it was replaced and imposed with an imperialist logic of what is defined as better. We need to move that to the side and we need to, people use the word decolonizing.

I’m not sure about that term. I wrote a book about decolonization, and now I’m questioning even the nature of the title of that. But I think the notion of really coming back to love ourselves as Indigenous peoples because we haven’t been loved. We weren’t loved by the colonizer, and then society all around us did not reflect love to us because we couldn’t find a place to express our culture. And unfortunately, this is what’s happening right now in this country.

Our language, again, is under threat. Our cultural practices are again under threat. And for myself, what I feel is that again, we are not liked in our own country, that there’s no love, that there’s a lack of empathy, there’s a lack of compassion. There’s a lack of love, what we call Aha. There’s a lack of love for Indigenous peoples again. So we have to love ourselves because our job is to love our deities and to love the Earth. And so if we want to embark on this healing journey and move towards a collective consciousness of healing the Earth, then we need to be able to find that love for ourselves again.

AL | Thank you for sharing all of this, and your work. What can western allies do? Children of colonialist settlers and the children of conquistadors, what can they do to be in solidarity with Indigenous peoples?

JH | Great question. I love this question. Walk behind or walk beside Indigenous peoples, but do not walk in front. I think I said a little bit earlier that kind of colonization is when the colonizer unpicks our culture and our ways of being and then kind of repackages it back and sells it back to us or tells us about that; don’t do that to us. I see that all the time. I see that in the food movements. I see that in permaculture. I see that in some of the spiritual movements. I see that in organics. I’m beginning to see it in regenerative, organic agriculture.

AL | New Zealand tourism.

JH | Oh, New Zealand tourism. Yes, absolutely. And also too, sport as well. The commodification of culture. It suits the purpose for sport. It suits the purpose for profit, monetary gain, but actually it’s denigrating our culture.

Our culture, like all other Indigenous cultures, isn’t sitting out there to do a pick and mix. I’ll take this bit of your language, I’ll have that bit. I’ll take that bit of a cultural practice, but yet you’re not taking all of the negative indices of no housing, low socio-economic status, low employment, all of the negative indices that Indigenous peoples all over the world face a result of colonization.

So there needs to be a check and balance around cultural misappropriation. There’s a role for non-Indigenous allies to walk with us, which is to walk beside or behind, but not in front, to not commodify or misappropriate our culture and then package it back to us and sell it as your own.

And then the final thing I’d say is, just around this term indigeneity, and the misappropriation of the term indigeneity. I’ve done a lot of thinking and writing about this over the years, but as Indigenous peoples in a settler-colonial context, like New Zealand, we only really know ourselves as Indigenous in relation to the “other”. So we only know ourselves as Indigenous in relation to the colonizer.

Before the colonizer arrived, we didn’t even know ourselves as Māori people. We knew ourselves as our independent nation states, our tribes and our tribal groupings. And so when I hear non-Indigenous people say, we need to indigenize ourselves, for me, all I hear is the pick and mix. I’ll take the close connection with Nature. I’ll take a few Indigenous words here. I might take the way that you culturally prepare your food, but I’ll just leave all of the hardship and the harm and the impacts of colonization for you Indigenous peoples to sort out. So I have a caution around that.

I think as we work together to evolve this new world that we are evolving and kind of co-creating together and thinking about how this could be, and I know our wisdom from our Indigenous peoples and my ancestors and your ancestors has a big role to play in that, but we need to do better and not commodify our way there along the journey,

AL | Tiokasin Ghosthorse, a Lakota elder and dear elder brother, who has been on the Deschooling Dialogues often says, there’s this trend amongst Westerners to say, well, we’re all Indigenous. What’s problematic about it, of course, on the one side, is this is a political claim, right? Indigenous people are fighting for their rights all over the world through the claim of indigeneity. So to just co-opt the term and make it imply coming back to the Earth or something generic is also part of the extension of colonial settler.

JH | Absolutely.

AL | And then the second aspect of what he says is: How Indigenous are you behaving? That’s the marker. Do you know the names of the plants and trees and flora and fauna around you? Do you know the healing properties? Do you live in circle ways? Are you embedded in your tribe, which is embedded in then broader ecology? If the answer is no, you can’t claim indigeneity as another interesting idea.

There’s something more happening here. And often what I think about, as somebody who’s been socialized in the West, on what the role of Western allyship could be, is to be good students of the dominant culture, to really understand the illness and the sickness and the disconnection of a separatist, materialist, rationalist, capitalist worldview. And if we do that, if we really were to internalize that, if we were to really internalize what it takes to prop up one western life, two to three thousand calories a day, and the iPhone and the globalized supply chain of extraction and amazon.com and all of that, we would fall to our knees in humility.

We would also stop exporting Western culture around the world through imposition, universalism, extraction and calling it financial inclusion or development or aid or what have you. And in some ways, that’s the best we can ask of Western allies is to stop the perpetuation of the supremacy of capitalist colonialist culture and stop imposing it on places in the world. And we need Western allies to do that and play that role within their cultures to be conscientious objectors of the master narrative.

JH | I absolutely agree, and I think as an activist about what we call a “flex-roots” level or grassroots level. Flax roots, we call it in our country here. I think about the everyday activism that people can do. We have a lot of young people all around the world, but in New Zealand as well, marching for climate change. Our young people want to know what to do. And they’re actually contributing more than my generation around how to be a good ally because what we call treaty discourse, the discourse around our founding document in Aotearoa has percolated and found its way through the fabric of society in New Zealand.

And so we have this younger generation that I’m hoping will be way more conscious. What I question, wonder, worry about is the connection back into self and back into Nature. And I can say this from probably 30 years of resistance work and of being an activist at the front lines of movements.

And then you’re just always in that resistance mode. You’re just always pushing against. And actually, when we are always doing that as Indigenous people, we miss the opportunity to work in those spaces where we can develop and where we can reclaim and where we can come back to know ourselves as Indigenous people.

So that’s just my little question mark around all of the school strikes around climate change. It’s like, well, what’s going to happen when you stop resisting? When do you stop marching? Then where are you going to go? Then what have we actually built together? What have we thought about together to create a new type of consciousness for the world that we want to leave for our mokopuna, our grandchildren?

AL | Beautiful question. That’s a beautiful way to end. Thank you so much. Thank you for being with me and for the work you do in the world. Thank you.

About:

Dr Jessica Hutchings (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Huirapa, Gujarati) is nationally and internationally recognised as a leader and researcher in Indigenous food systems and Māori food and soil sovereignty, she is a founding Trustee of the Papawhakaritorito Charitable Trust that works to uplift Indigenous seed, soil and food sovereignty and Hua Parakore (Māori organics) through research, development and community practice. She lives on 12 acres and is a Hua Parakore verified family food grower. She has been a member of Te Waka Kai Ora – the Māori Organics Authority for the last two decades.

Jessica is also a widely published author, including recent books, Pātaka Kai Growing Kai Sovereignty (Massey Univeristy Press, 2025), Te Mahi Oneone Hua Parakore: A Māori Soil Sovereignty and Wellbeing Handbook (Freerange Press 2020), and Te Mahi Māra Hua Parakore: A Māori Food Sovereignty Handbook (Te Tākupu, 2015). Dr Hutchings has been working at the crossroads of Indigenous knowledge and environmental wellbeing for the last three decades and is passionate about Indigenous social justice, organic farming and self-determination. She was named as a finalist in 2023 for the New Zealander of the year in the Environment category as well as being named one of New Zealand’s top 50 influential women in food and drink.

For further information see:

jessicahutchings.org.nz

https://www.papawhakaritorito.com/

Social media details:

Instagram: @papawhakaritorito_trust

https://www.facebook.com/PapawhakaritoritoCharitableTrust/