Toward an Eco-Social Contract for Regenerative Futures

This essay introduces the eco-social contract as a visionary governance framework that integrates power, transaction, and care across state, market, and commons. In contrast to fragmented, transactional development approaches, it emphasizes relational processes, civic agency, and bioregional stewardship. Drawing on political philosophy, Indigenous worldviews, and Integral Theory, the piece calls for a multi-level, polycentric renewal of human and institutional relationships — one rooted in empathy, complexity, and systems thinking. Ultimately, it’s a call to rebuild the social contract as a web of care, capable of responding to ecological collapse, inequality, and institutional breakdown with co-creative resilience.

featured image | Photo by Erik Mclean

Introduction

Intractable development challenges cannot be resolved through technical or financial solutions alone. They often arise from collective action failures shaped by invisible social norms, belief systems, and institutional structures as well as individual values and behaviors. Achieving meaningful progress necessitates shifting power relations and realigning aspirations and value systems to foster collective well-being. Hence, there is greater need for more integrated approaches – those that combine relational dynamics and political process with the technical and quantitative tools that have long dominated traditional development paradigms. States, private sectors, and civil societies all have critical roles to play as agents of change. Yet their efforts are often fragmented, constrained by unsynchronized relationships that hinder collaboration and systemic outcomes.

What’s missing is a shared framework – one that enables harmonization and mutual alignment across diverse actors, inviting fluid collaboration and systems thinking for broader societal transformation. Understanding the political, economic, and social dimensions of power, resource flows, and decision-making is essential. This calls for attention to structure, ownership, agency, and inequality – not as abstract categories, but as lived realities.

This article introduces the concept of the eco-social contract: a relational and integrative framework for navigating the intertwined governance challenges of economic growth, social justice, and environmental sustainability. It offers a relational framework to navigate and rebalance the dynamics of power, transaction, and care across the state, market, and commons—opening up pathways that are inclusive, regenerative, and co-creative.

What is Eco-social Contract

A social contract, though it can be calibrated in a multitude of ways, fundamentally represents commitment and agreements to living well together. Rooted in classic political philosophy, the social contract theories have evolved over time. In 17th and 18th century, thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), John Locke (1632-1704), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1772-1778) and Immanuel Kant (1742-1804) conceptualized it as a foundation for legitimate governance. In modern times, social contract has been revitalized as a framework for considering new principles and practices that reflect evolving choices and values in a changing world. Significant contributions in the latter half of the 20th century, as compiled and compared by Weale (2020) include Buchanan and Tullock’s The Calculus of Consent (1962), Grice’s The Grounds of Moral Judgment (1967), Gauthier’s Morals by Agreement (1986), Barry’s Justice as Impartiality (1995), Scanlon’s What We Owe to Each Other (1998), and Rawls’ A Theory of Justice (revised 1999). Today, amid mounting ecological and social crises, new articulations of the social contract are emerging that center interdependence and planetary boundaries.

Intensifying climate crisis and widening inequalities have fractured traditional contracts. Yet these same pressures are opening space for a more just and regenerative vision – one that harmonizes human activities with natural systems. Contributions such as Huntjens’ Natural Social Contract (2021) and those from the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD)’s global studies underscore the urgency of rethinking governance frameworks for our common future.

Countries like Ecuador (in 2008) and Bolivia (2010) were the first countries to implemented legal frameworks that grant nature legal rights and protections, incorporating indigenous thinking of Pachamama and representing early models of eco-social principles in practice (Kauffman and Martin, 2021). Though implementation remains complex, these experiments reflect growing yearning for inclusive, future-oriented systems. Furthermore, several countries and communities in the global North are moving away from traditional growth-centered notions of progress. New Zealand and the European Union are incorporating well-being frameworks into public policy (Kempf, et al., 2022).

The proposed eco-social contract intends to bring together all relevant stakeholders—citizens, state actors, the private sector, and the often-overlooked ‘silent’ stakeholders, future generations and natural systems. Regenerative development depends on relationships, agreements, and incentives that shape behavior, influence institutions, and ultimately determine social, economic, and ecological outcomes.

This framework complements traditional quantitative approaches with relational and contextual tools, addressing often-overlooked factors such as ecological health, cultural sensitivities, institutional dynamics, and social identities. It introduces a political economy lens rooted in three interrelated dimensions: power, transaction, and care, corresponding to the functional logics of the state, market, and commons, respectively.

The eco-social contract strengthens four interconnected capacities – state, market, civic, and bioregional – as levers for transitioning toward regenerative, inclusive societies rooted in well-being. These capacities provide entry points for context-specific transformation, enabling systems to self-correct through feedback loops and the renewal of relationships and resources.

By integrating power, transaction, and care, eco-social contracts offer a fresh lens for navigating the complexities of modern governance and advancing sustainable outcomes for all stakeholders. At the heart of this approach is care, a relational design principle that ensures governance and economic systems serve both ecological and social well-being.

In sum, the eco-social contract provides a framework to:

- Gain clarity on complex challenges.

- Foster systems thinking and interconnection.

- Nurture care and agency to co-create viable solutions tailored to specific contexts.

The Fundamentals of the Framework: Power, Transaction, and Care

The state, market, and commons each operate through the dimensions of power, transaction, and care, which shape how they interact and fulfill their respective roles in society. Traditionally:

- State operates through power to uphold the rule of law, maintain order, deliver public services, and create enabling conditions for livelihoods, enterprise, and social stability.

- Market operates through transaction, using exchange and pricing mechanisms to allocate resources and create economic value.

- Commons, supported by communities and commoners, are rooted in care – fostering collective well-being and cooperation to meet shared needs.

In the eco-social contract framework, the state, market, and commons each embody the dimensions of power, transaction, and care within themselves, while dynamically interacting to shape society. The state, as a power system, can enact inclusive policies like universal healthcare or conditional cash transfers (care), and use public procurement to deliver essential services such as education and infrastructure (transaction). Markets contribute by advancing circular economy innovations, adopting fair labor practices to strengthen community resilience (care), and forming coalitions to influence industry standards (power). Communities—both physical and virtual—engage in commoning processes to self-organize around shared resources (power) and develop social and solidarity economies (transaction) rooted in mutual care and collective well-being.

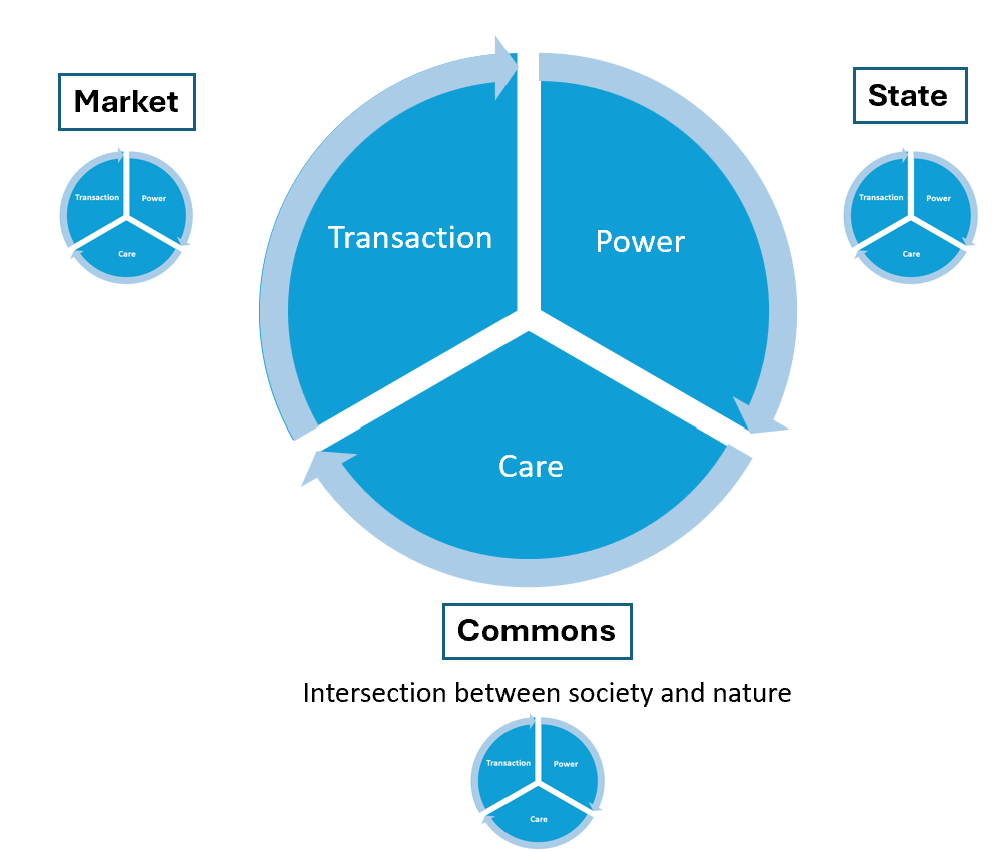

Figure 1: Self-regulating Cycle of Human/Institutional Relationships: Care, Transaction, and Power

This nested and interconnected structure reflects the interdependence of the three dimensions:

- Care fosters empathy, responsibility, and well-being, grounding societal relationships in shared values.

- Transaction structures resource exchange and ensures economic and organizational sustainability.

- Power governs and regulates these relationships to uphold justice, balance competing interests, and prevent exploitation.

When held in dynamic balance, these dimensions form a self-regulating cycle of human and institutional relationships:

- Care directs power: Care ensures that power serves the well-being of people and ecosystems, rather than domination or exploitation.

- Transaction structures care: Transaction provides the organization, accountability, and sustainability needed to implement and scale caring practices effectively.

- Power regulates transaction: Power acts as a check on transaction, protecting the commons, and preventing exploitative practices in markets and exchanges.

Societies suffer when these dimensions are imbalanced—when care is subordinated to transaction, or power is exercised for control rather than protection. For example, ecosystems treated solely as commodities erode communal well-being and the moral fabric of society. Similarly, captured states may divert public power toward elite interests, cutting funding for essential services and environmental protections. These distortions fracture the social contract and diminish the legitimacy of governance systems.

To remediate these risks, eco-social contracts must be inherently oriented toward process and relationship. By being attuned to relational dynamics and systemic flows, they enable adaptive responses to emerging challenges and help restore dynamic balance. For it to take root, functional states and markets must operate within a larger context of care—ensuring their actions are guided by collective well-being and long-term sustainability (Table 1).

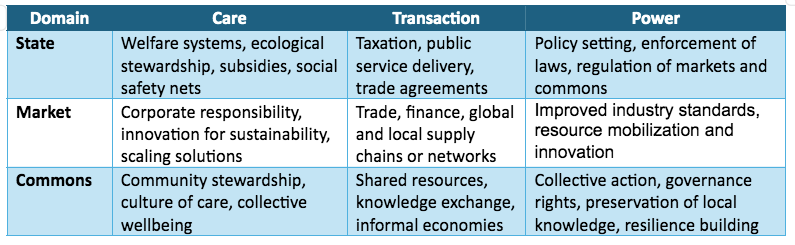

Table 1: Interplay of Power, Transaction, and Care within State, Market, and Commons Interactions

Note: The examples listed under each domain and dimension are not exhaustive, nor are they strictly exclusive. Rather, they are meant to illustrate the original spirit or positive potential that each dimension – care, transaction, and power – can bring.

Importantly, a genuine eco-social contract also requires transforming the power relationships that underpin ecological degradation and social inequity. This transformation is supported by decentralized networks of civic and business communities, where community becomes a principle of care that unites individuals and institutions. To ensure policy coordination and structural support, state-level institutions must align with these networks, responding to local realities and reinforcing the collective capacities of citizens and enterprises. Businesses can form regional hubs alongside civil society actors to embed eco-social values into commerce, innovation, and shared responsibility.

This polycentric structure leverages network effects to catalyze systemic change—weaving together state, market, and commons actors into a collaborative “Web for Life.” It balances centralization for coordination with decentralization for local adaptation, creating the conditions for inclusive, society-wide participation in regenerating our ecological and social systems.

Operationalizing the Framework: Integrated Capacity Building

Governance structures shape how state and non-state actors interact, define power relations, and make decisions for the collective good. To meet today’s complex challenges, these structures must embed care as a guiding principle – enhancing society’s capacity to steward both people and planet. When applied to governance and economic systems, care can shift them from extractive to regenerative, prioritizing equity, well-being, and sustainability. Such transformation engenders both institutional safeguards (e.g. anti-monopoly regulation, participatory decision-making) and human capacities, such as emotional intelligence and systems thinking.

Civic actors play a pivotal role in catalyzing decentralized networks that can scale care, hold institutions accountable, and align markets with regenerative principles. However, civil society is not inherently cohesive. In contexts marked by fragmentation or polarization, bridging divides and fostering collaboration becomes essential to embedding care-centered governance across micro, meso, and macro levels, and across sectors.

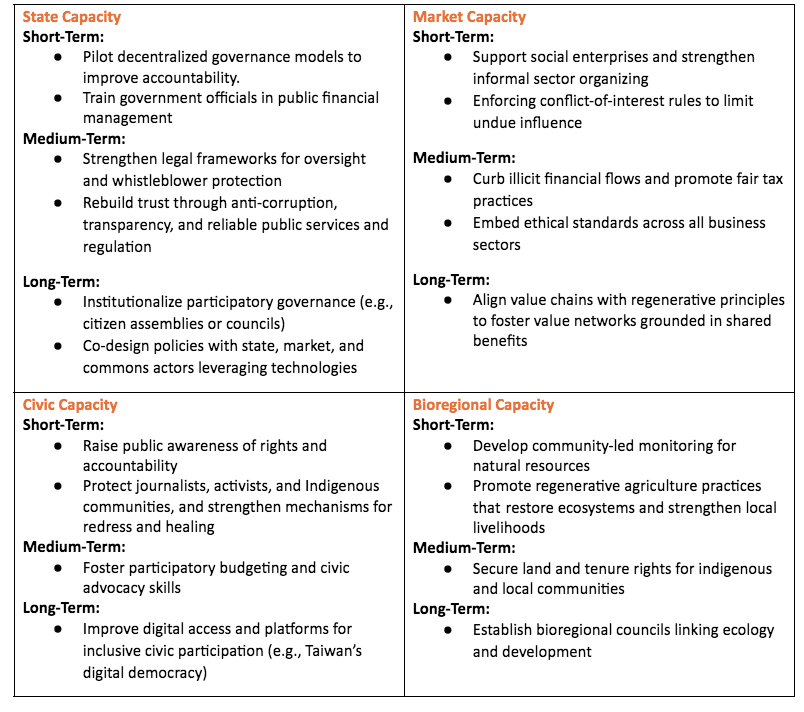

These efforts lay the groundwork for an integrated approach to capacity building at all domains:

- State Capacity: Design inclusive policies grounded in care and ecological stewardship. Strengthen legal and institutional frameworks to enforce rights, provide public services, and uphold social stability

- Market Capacity: Support regenerative business models and transform value chains to promote equity, decent work, and environmental sustainability.

- Civic Capacity: Empower civic actors to foster social accountability, scale community innovations, and revitalize the commons as a shared way of life.

- Bioregional Capacity: Ensure ecosystems thrive with biodiversity and ecological integrity in ways that are locally and regionally relevant.

Most importantly, capacity-building efforts across state, market, and civic sectors must converge toward social capital formation, strengthening social cohesion and laying the foundation for inclusive, collaborative societies capable of addressing unique challenges and opportunities in local contexts.

While the establishment of a commons-based eco-social contract that values every individual and form of life takes multipronged efforts, it is essential for regenerative development. Building this foundation requires large-scale, open and inclusive dialogues within and across communities to foster civic engagement and social accountability. Such efforts help reduce power asymmetries by creating checks and balances among state and non-state actors, while also making space for restorative justice. Strengthening civic discourse and capacity -through meaningful conversations, shared sense-making and coordinated action -is crucial to counterbalance state-market power dynamics, prevent elite capture, and address inequality. Ultimately, individuals, beyond their professional roles in their employment, play a vital role in restoring bioregions, revitalizing community connections, and nurturing responsible citizenship.

Application: Addressing Elite Capture through Eco-Social Contracts

Each country’s path toward integrating social inclusion and environmental sustainability into its development paradigm is shaped by its political processes, institutional histories, and cultural context. Governments govern differently depending on how power is distributed and exercised. Transforming entrenched power relations requires more than technical interventions – it invites a whole-of-society effort to empower citizens and enable governments to challenge vested interests.

This section applies the eco-social contract framework to one of the most persistent development challenges: elite capture, particularly acute in resource-rich or fragile settings where governance is dominated by narrow interests. The central question becomes: How can elite-driven governance models be transformed into citizen-focused systems?

The eco-social contract reframes this challenge by addressing not only technical gaps, but also the structural and relational dynamics that sustain elite capture. Since power and resources are often concentrated among elites, transformation involves shifting incentive structures, regulating undue influence, and encouraging behavioral change so elites contribute to – rather than block -inclusive development (World Bank, 2022). Three interdependent strategies support this shift:

- Building stakeholder capacity: Strengthen the state, market, civil society, and bioregional actors to operate in complementary and reinforcing ways.

- Transforming power dynamics: Close governance gaps, implement redistributive policies, and strengthen local actors to counterbalance asymmetries.

- Fostering locally relevant reforms: Tailor reforms to local contexts, support legal pluralism, and engage communities in co-creating monitoring systems and feedback loops.

At its root, elite capture stems from a disconnect between elites and shared well-being. A scarcity mindset sustains systems where power is concentrated, and public resources are unequally distributed. Reframing governance as a relational process – centered on care, mutual responsibility, and collective flourishing – offers a powerful entry point. This shift begins with honest dialogue and coalition-building across levels. Governments, civil society, and the private sector coordinate efforts to advance inclusive reforms and redirect governance toward the common good.

Ultimately, nation-building depends on citizens’ capacity to participate meaningfully and hold institutions accountable—alongside state and market actors willing to innovate and share power. The eco-social contract highlights the need for integrated capacity-building and rebalanced relationships. Table 2 outlines examples of policy actions that can support inclusive transitions, but these must be adapted to fiscal realities and available capacity.

Table 2 Illustrative Reforms to Rebalance Power and Address Elite Capture through Eco-Social Contracts

Relational Pathways to Systemic Change

Solving deep-rooted inequalities requires more than isolated reforms or individual capacity-building. It demands a fundamentally relational approach—one that focuses on the quality of relationships and the design of processes that enable collective wisdom, coordination, and care.

This involves aligning multiple dimensions of development, drawing inspirations from Integral Theory (Wilber, 2000):

- Interior Dimensions (Values and Culture): Cultivating societal values rooted in care, empathy, and ecological awareness through practices of arts, eco-literacy, and relational skill-building.

- Exterior Dimensions (Systems and Policies): Designing institutional mechanisms – governance structures, legal frameworks, and participatory processes – that protect ecosystems and uphold equity.

- Individual and Collective Perspectives: Balancing personal agency with communal well-being using technologies such as participatory methods and Warm Data Labs.

When these inner and outer, individual and collective dimensions are integrated, eco-social contracts become not only conceptually meaningful, but practically actionable. A deeper awareness of what connects, conditions, and divides people—especially in the invisible interior realms—is essential for real progress.

Eco-social contracts operate across multiple levels: individual, organizational, national, and international. Their interconnectedness can catalyze systemic transformation. For instance, when a business adopts eco-social principles – embedding fair labor, environmental stewardship, and community engagement – it can influence peers and shift standards sector-wide. Similarly, pioneering countries that embrace inclusive, regenerative governance can inspire shared learning and foster regional integration to enhance ecological, social, cultural and economic vitality of the region over the time.

Eco-social contracts operate across multiple levels: individual, organizational, national, and international. Their interconnectedness can catalyze systemic transformation. For instance, when a business adopts eco-social principles – embedding fair labor, environmental stewardship, and community engagement – it can influence peers and shift standards sector-wide. Similarly, pioneering countries that embrace inclusive, regenerative governance can inspire shared learning and foster regional integration to enhance ecological, social, cultural and economic vitality of the region over the time.

This relational web means that no action exists in isolation. Connections across sectors, regions, and scales amplify change. By reorienting development toward relationship and process, ripple effects can take hold -transforming both local realities and the global landscape.

By illuminating the dynamic interplay of power, transaction, and care within the state-market-commons nexus, the eco-social contract becomes more than a framework – it is a living relational field for social renewal. This process-oriented, participatory approach moves beyond expert-led, outcome-driven models. Instead, it invites practitioners, change agents, and citizens alike to engage with complexity, attune to context, cultivate care, and co-create futures grounded in mutual responsibility and shared well-being.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to express heartfelt gratitude to Forrest Landry, whose direct guidance, encouragement, and foundational metaphysical work have been a continual source of inspiration in shaping the ideas behind the proposed eco-social contract. For his work involving triples, please refer to An Immanent Metaphysics (2009, 2023).

References

Kempf, I. and Hujo, K (2022): Why Recent Crises and SDG Implementation Demand a New Eco-Social Contract

Kauffman, C. and Matin, P. (2021): The Politics of Rights of Nature – Strategies for Building A More Sustainable Future

Huntjens, P. (2021): Towards a Natural Social Contract – Transformative Social-Ecological Innovation for a Sustainable, Healthy and Just Society

Scott, J. (2014): The Major Political Writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Two Discourses and the Social Contract

UNRISD (2023): Global Study on New Eco-Social Contracts

UNRISD (2022): Crisis of Inequality – Shifting towards a New Eco-Social Contract

Weale, A. (2020): Modern Social Contract Theory

Wilber, K. (2000): A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science, and Spirituality

World Bank (2022): Reimaging Government for Good

Reorienting development toward relationship and process in order to balance personal agency and communal well-being as well as finding the sweet spot between centralized coordination and decentralized adaptation is a fascinating vision for eco-social contracts. The potential for thriving, vibrant communities in global communication is endless. And better yet, it is actually possible. Thank you.