Rupture and Reweaving

Rupture and Reweaving

GRASS COCOON | JUNE 2018

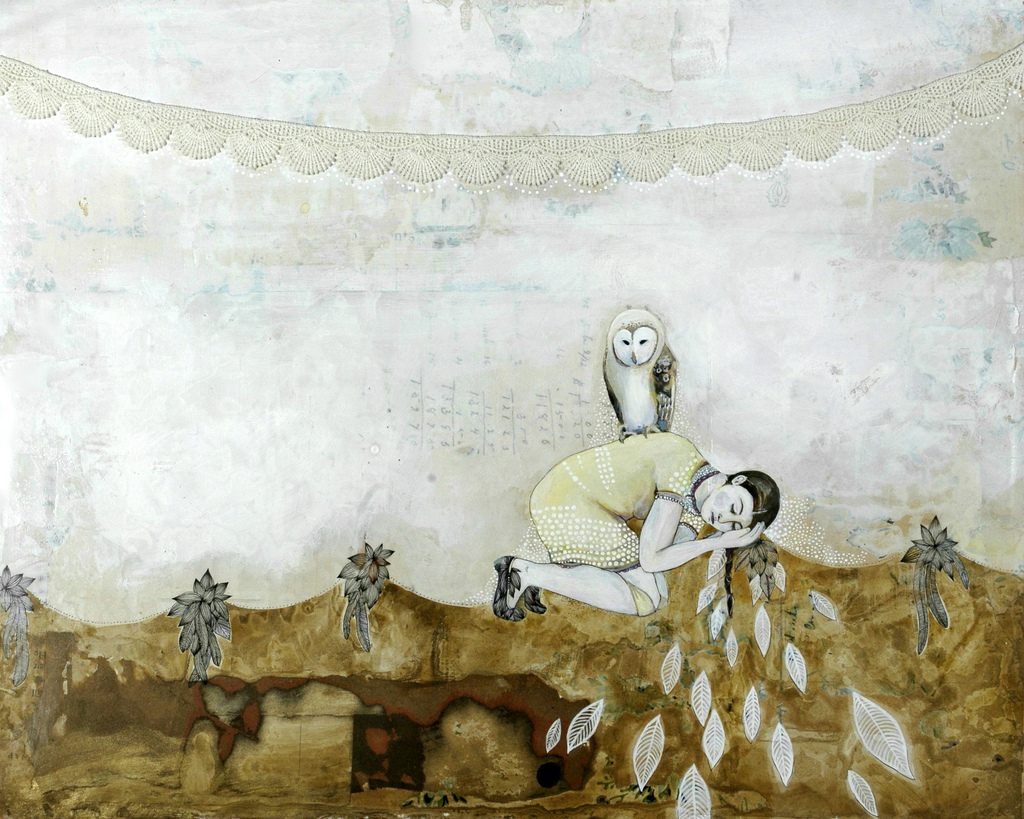

I contemplated making Grass Cocoon for two years. The image was persistent and it took up residence in my imagination, so I finally committed to making it and enlisted the help of friend, naturalist, educator, basket-maker, and now beloved model, Nicole Larson.

I doubted and judged this project every step of the way, even on the day that I made it. If I hadn’t made a plan with Nicole to meet at a certain time and day, I surely would have doubted this piece into non-existence, and I would likely be a librarian right now instead of an artist.

This piece changed my life. It was shared widely on social media and was well received (aside from abundant concerns about ticks and chiggers.) From this experience I learned to just make the things I wanted to make, without judgement.

I learned that it is possible to scrutinize an idea, and to apply a formal decision-making process to each piece, without assigning value. I decided to let other people decide if my work has value to them, and to remain confident about the essential role of my work in my life. After all, when everything is said and done, these are experiences I want and need to have.

In short, I learned to wrestle the voice of self-doubt into submission, at least long enough to make these pieces, and give them a chance to see the light of day.

LACE SKIRT | JULY 2019

Driving through Silverdale, Washington, I passed an abandoned lot that was full of Queen Anne’s Lace. The plants were enormous and there were hundreds of them. As I continued driving, the Queen Anne’s Lace took root in my imagination, and before long I envisioned a skirt made of the stuff, with a woven cotton bodice.

I returned to the lot the next day and harvested a small portion of the flowers on the site. I worked on the piece for two days, storing the work in progress upside down in a bucket of water to keep it happy overnight.

I didn’t have a model lined up and the piece needed to be documented right away, so I decided to wear it myself. Right before the shoot, it seemed to me that the white cotton of the bodice was just too white. I wanted to dye it a light pink, so I scoured my house looking for food coloring or dye, or anything liquid and red that I could quickly apply to the cotton. Alas, all that I could find was an ancient bottle of Nyquil. It was in fact liquid… and red. So, reluctantly I watered down the Nyquil, brushed it onto the bodice of my skirt, and went to the shoot.

My husband shot the pictures, conferring with me about the angles, distances, poses, and light. Our sweet dog Oso was with us in the field that day and was intrigued by my new Nyquil smell.

This piece was, and continues to be, a joy.

EXTENSIONS | DECEMBER 2020

This piece was a product of spending many hours exploring my favorite Port Townsend field. I had long felt a profound connection to this place and was trying to find a way to express my feelings of devotion and love for it. I wanted to find a visual way to express my deep feeling of connection to this land. When you look long and hard enough, sometimes you get lucky and land on an idea that feels right. Having had very long hair my whole life, a braid seemed like a natural way to connect my model to the earth. This piece came to me from wherever ideas come from, and I will be forever grateful for it.

In both “Grass Cocoon” and “Extensions” my model, Nicole, could not walk away from her situation. She was literally bound to the Earth. She was also profoundly at peace with her condition. We cannot escape our relationship with the natural world. There can be no “us” without “it.”

KATRINA | SEPTEMBER 2021

Over the years, I have come to know and love the bull kelp that I find washed up on our Puget Sound beaches.

On a mid-September day, I sat on the beach, lamenting the passing of summer and the likelihood that this piece would have to wait until the following year. A few moments later, Katrina ran past me on the beach. I’d never seen her before. I’m pretty sure my heart skipped a beat or two. On her way back, I blurted something out about needing a model for a project and would she consider working with me. As luck would have it, she didn’t think I was crazy, and my kelpy vision came to fruition the very next day. I’m still counting my lucky stars.

I built this piece directly on Katrina’s body, and yes, the thin straps of the bodice are indeed made of kelp. Making this piece and working with Katrina, the kelp, the tide, and the sun, felt like a crazy miraculous dream.

GREY STUDY WITH ALISON | AUGUST 2022

The brutal, inconceivable, utterly devastating truth of the matter is that I lost my beautiful 23-year-old son, Corbin, to an accidental overdose on February 5th, 2022.

Since then, my life has been a complicated grueling mess. No idea which way is up. No thought in my head except Corbin. Mental and emotional anguish. No interest in anything. No motivation except my own survival, and that of my daughter and husband. My creativity came to an abrupt halt. The agony of this loss has been all consuming. There is more to say, but not here.

Grey Study with Alison is a project that I started working on before I lost Corbin. I took a stab at it a year and a half ago and couldn’t pull it together. My model lived too far away. The weather would shift before she could meet me. And the fennel skirt deteriorated due to moving it in and out of the car too many times. I gave up on it for a time and then later asked my dear friend Alison if she would model for me. Her lovely mom, Joy, an accomplished knitter, agreed to knit a sweater for the project. I recreated the fennel skirt this spring and we waited for a foggy morning to shoot the piece. We got our chance on Tuesday, August (we call it Faugust here in Port Townsend) 23, and I was able to pull myself together for the project despite inertia and self-doubt. I cried a lot afterward.

The piece seems to capture the vastness of my grief and the acute sense of loneliness that I’ve felt since losing my son. If I had to assign a color to the grief experience it would be the color grey.

Alison was the perfect model and muse for this project, not only because her hair is the most lovely warm grey color that worked so well with the color of her sweater, that worked so well with the color of the dried fennel stalks, that worked so well with the cloth with which I wove them together. And not only because of the subtle gestures of her head and hands and shoulders that somehow conveyed my sadness and aloneness so well. But because without her, I would not have survived these last 7 months.

PHOENIX FROM THE FLAME | DECEMBER 2023

When I lost Corbin it felt like I died too. Everything went dark. Eventually, I discovered that there was a tiny ember still burning in me somewhere, and I knew that I needed to keep it alive. I needed to feed it. That’s where the idea for this piece came from. As I was preparing the materials for this project this summer, Sinead O’Conner, a hero of mine, tragically died. Like me, Sinead also lost a son in 2022, and I think maybe she couldn’t keep her ember going. I decided to dedicate this piece to her. It’s the least I could do for my wild courageous hero.

To all of you who are experiencing trauma, pain, or loss, please try to keep your ember going. I will do the same.

MARLO WITH QUILT IN CEDAR GROVE | DECEMBER 2024

The idea for this bark blanket dropped into my mind while I was admiring various pieces of bark that adorn my studio. I chewed on the idea a bit, and settled on the unlikely concept of a patchwork quilt made of bark.

I feel in retrospect that this project blends the tradition of the patchwork quilts of my New England upbringing, with the traditional cedar bark clothing of the Northwest Coast Native American cultures. My being an adoptee of the Northwest Coast landscape, this mixture feels apt.

This project is yet another attempt on my part to describe my belief that nature can heal and comfort us, and that we are part of the fabric of the natural world.

Artist’s Statement

I work in nature to address issues concerning humanity and the Earth. I am profoundly moved by the natural world, and I am fortunate to live close to beaches, forests, and fields that inspire and sustain me and also provide me with the raw materials required to make my work.

My goal is to express, as beautifully and as compellingly as I can, the contents of my inner world and imagination, as well as my preoccupation with the relationship between humans and nature. With my work, I attempt to describe a connectedness between us and our environment that seems to have been all but forsaken. I hope to nurture this dynamic relationship, which is our birthright and obligation, and to perhaps even rekindle and reawaken a yearning for it in others. Simultaneously, I hope to satisfy my own need to embed myself in nature.

Issues that are of preoccupying concern to me include racism, sexism, climate change, patriarchy, and capitalism. Movements that I support and hope to advance include Black Lives Matter, intersectional feminism, LGBTQ+ rights, and Indigenous Peoples’ rights. I see an obvious correlation between the mistreatment of the Earth and the mistreatment of women and all marginalized human beings.

Finally, I wish to respectfully acknowledge that the land upon which I live and work is unceded ancestral land of the Coast Salish peoples.

About Jeanne Simmons

Jeanne was born in coastal New Hampshire and grew up in a raucous household with four siblings. She graduated from the Maine College of Art in 1991 with a BFA in Sculpture. Upon graduating, she attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture.

In 1992, Jeanne moved to Chicago to attend graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She couldn’t cope with city life, so she drove west, eventually settling on Vashon Island, WA, where she later met her husband, Gunter Reimnitz, who is also a sculptor.

Jeanne’s work has been featured in numerous national and international publications. She is currently working with filmmaker Ward Serrill (The Bowmakers and The Heart of the Game) on a film about her work and process.

Accompanied

Accompanied

In the fall of 2024, Hurricane Helene devastated North Carolina. Elsewhere, torrential rains collapsed mountainsides, swallowing villages, towns, and bodies in miles of mud. Volcanoes poured lava into inhabited spaces, lacing water with sulfur. Wildfires reduced entire landscapes to char, erasing homes and all forms of life that once inhabited them.

Communities, Presence disrupted. Destroyed. And now decomposing.

Nature is rising to interrupt human abuses of power. Yet, those who wield domination continue efforts to obliterate communities, histories, wisdom traditions, and, of course, the Earth. Reverence for life feels engulfed once again in the white noise of unbearable anguish.

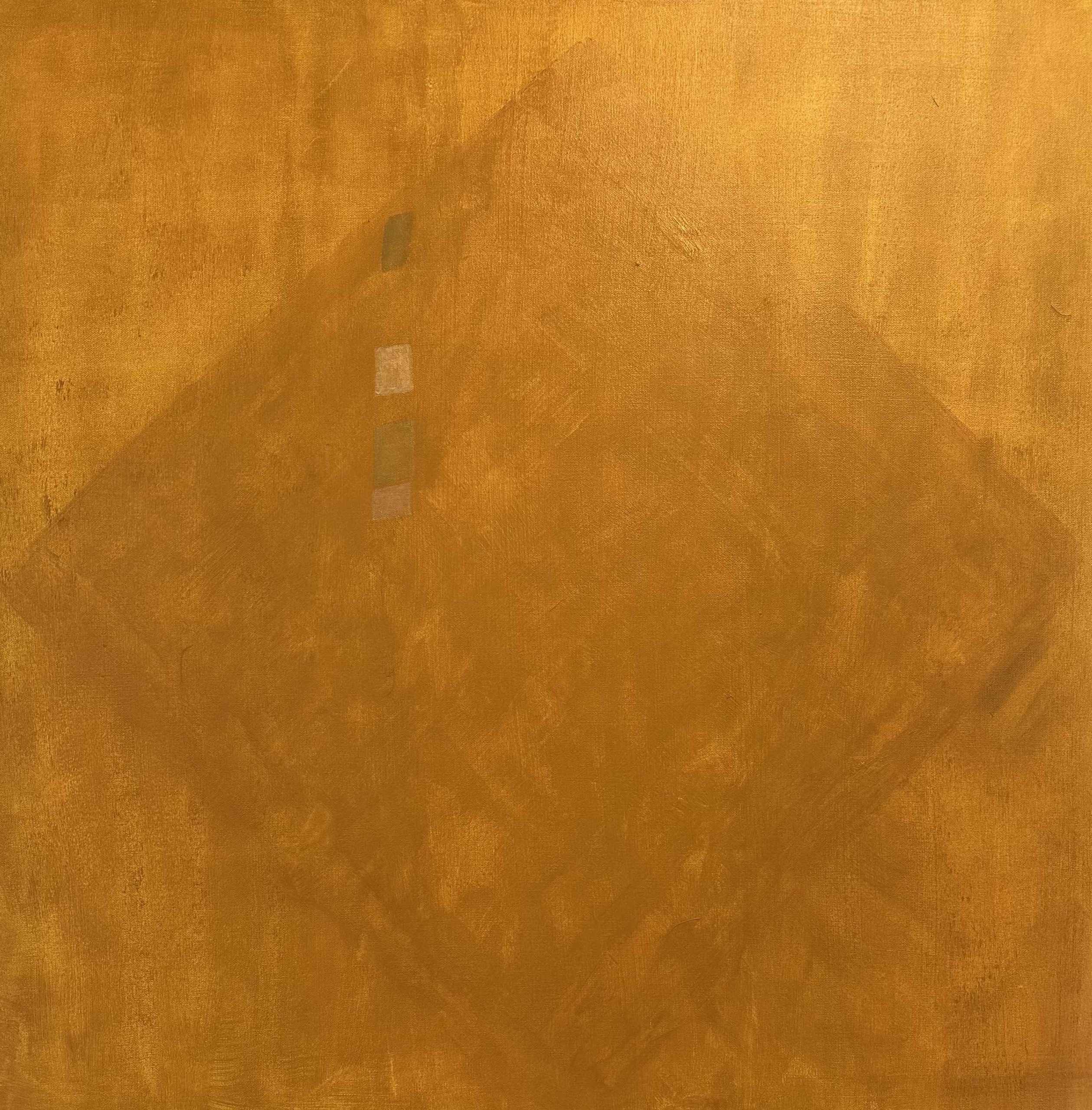

That white noise invaded my studio, my capacity to metabolize such devastation. For months, I sat before a blank canvas, waiting for a break in the static, a glitch in the white noise to open a way forward.

In time, light filtered in through the window illuminating the canvas and its structure from behind. There it was! The window, literally becoming the portal of possibility.

On a palette I poured gold, bronze and yellow hues, letting the brush bring these to the canvas as it chose too. Ethereal light penetrated the canvass from behind, forming a rich invitational ground I could trust to hold what needed to be seen. Soul-stunting white noise giving way to “seeing what is felt”.

.

Something more was coming…

Devastation, and yet, a doorway… Light! And the shadow of a bird presencing.

I stopped, needing to weep a while, recognizing the burning and the birthing that had arrived. So Painful and Possible. I sighed deeply, into continuing…

Wind-swept char covering everything, dimming even shadow bird… but still… Light, like Love, persisting.

Accompanied.

Always, She is there, appearing in the convergence – an outline now upon the threshold of Light. Reminding me to let go, let go, let go. Be brave enough to see. And in the midst of it all to blindly trust Light, trust Love. Tenderness holds me. She enters and Peace continues to form.

The white noise gone, I am touched deeply by what remains – by the seeds that endure. Hope arrives through the tender act of presencing pain. Once again, we are held in creative light, a tender radiance that expands the limits of our present conditions.

As birds do, may we bear witness to what must be seen, and offer new seeds to the continuum of our becoming – flying amidst, and with, the Beauty that arises and calls us forward.

About Mary Putera

Mary Putera is an organizational consultant and Associate Professor in the Expressive Arts Department at Lesley University in Boston, MA. She trusts sensory-centered artmaking as an inherent human capacity – a practice of wisdom and relational interdependence with all life. Facilitating and participating in community artmaking is one of her greatest joys. Mary’s work seeks the places where Beauty is flourishing, and the invitations Beauty extends to us—to form life with Them, so that all beings may flourish together. https://theartofintegrity.org/

Passing Time

Passing Time

featured image | Annette

The silent dark is broken by the padding of feet, drawing me slowly out of the depths of dreaming. The bedroom door opens a fraction, letting in a thin rectangle of light, then closes, drawing out the light once again. Something else has slipped in with the light. I strain my ears, listening for clues, but there’s only a sixth sense of another presence. Then comes a sigh, softer than the gentlest breeze, and a small sleepy body slips in beside me. Inside the covers, a cold foot presses on my belly.

On winter mornings the darkness lingers. I expect my children to wake with the light, later each morning, until the solstice, but that isn’t what happens. Instead they wake early, 6am, 5am, sometimes even 4am, and shuffle around the house in the cold, waiting for the sun, expecting breakfast and stories and warm fires from me. Every winter I tell them they mustn’t wake so early. Tell them it isn’t fair. Tell them I won’t. But I always do.

They try. For minutes at a time they hold back their restless energy and lie in bed, searching their senses for morning clues. They listen for the stillness before dawn, the distant rush of cars, birds stirring, a change in the feel of things. . . They listen until the exquisite pain of anticipation propels them out of bed and into the new day.

This morning though, I am given a reprieve. My son’s breath is steady, his mouth open, sleep has claimed him once again. It’s still dark and will be for hours yet. But I’m awake now and restless. I need the toilet. My arm is going numb where his head lies, cutting off my circulation. For a moment I wonder about that, how much heavier we become in sleep. How much there is inside our heads. How much we don’t use. I think about weight too, how there are different kinds of weight. The sort we measure on a scale, and the other sort. The heaviness that some people carry around them – their shadows filled with the past. I’m restless, but I’m putting off the inevitable. Whoever heard of waking a sleeping child? My oldest daughter cries out and I tense, but it’s quiet again. A passing fear.

There’s nothing heavy about my children, no shadows weighing them down, and I wish I could always keep it this way. I wish I could ward off the troubles of life, but we all have our own journeys to make. As Kahlil Gibran wrote so beautifully in The Prophet, ‘Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of life’s longing for itself. . . You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth…’

I am the bow, but not the archer. I’m not the maker of a destiny but the enabler. And what a responsibility that is. To be stable and strong for them. To give my children gladness, to teach them empathy and compassion and confidence. To show them how to find their way into the flow of life. To help them become truly human.

I am the bow, but not the archer. I’m not the maker of a destiny but the enabler. And what a responsibility that is. To be stable and strong for them. To give my children gladness, to teach them empathy and compassion and confidence. To show them how to find their way into the flow of life. To help them become truly human.

Or is it my children who are teaching me what I need to know? In so many ways they’re already wiser than me. I tell time by my children, counting the moments I still have. They tell time by embracing life. Days, months, years, slip through my fingers, while they fill each moment with themselves. I reach back into the past, strain forward into the future. They live in the now. Naturally. Easily. The way all wisdom traditions tell us we should.

I’m lying here awake, feeling the weight of my own shadows, my mind flitting from one thought to the next. I plan dinner, write a shopping list in my head, worry about the bills, panic about outfits for the school fancy dress ball, nudge my husband until he stops snoring and feel guilty because I’m not up already, using this rare solitary time for something more useful. But what sweet comfort, to be sandwiched gently between my husband and my son on this cold morning, feeling my son’s breath warm upon my cheek. How could I possibly regret anything so precious?

It’s no good though, my arm is hurting and I have to move it. I try to do this gently, hoping I can slip it out from under my son’s head without disturbing him. But he wakes and smiles at me, a face so clear I can see it in the almost dark.

‘Best mum,’ he says.

Then.

‘Mummy, let’s talk about mysteries.’

He’s sitting up, eyes bright, mind spinning with possibilities and I’m amazed at how smooth his transition is between sleeping and waking. I’m slow, dragging myself out of unconsciousness, grasping uselessly at my dreams which slip effortlessly away, tantalisingly out of reach. My brain stays fuddled, but he’s bright. He’s here. Now. And I want him to always be like that.

‘Mysteries?’

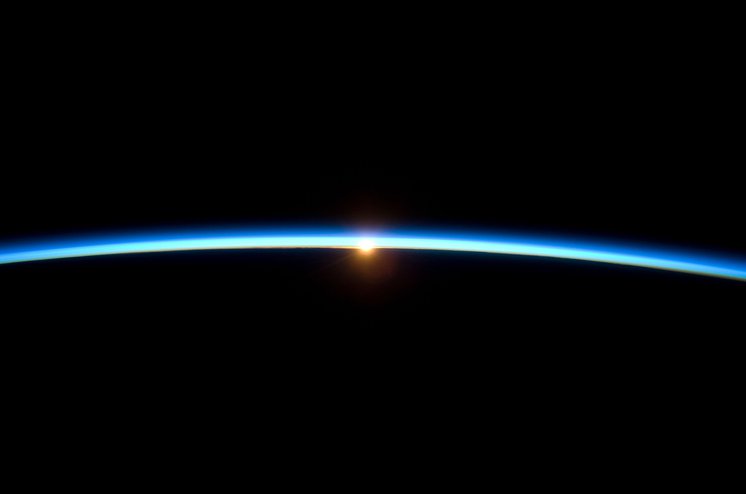

‘You know. . . Infinite space, imaginary numbers . . . What’s underneath a whirlpool? Inside a blackhole?

I think about blackholes. How scary they sound, the way they absorb energy, their appetite insatiable. Humanity is like that, sucking up the earth’s energy. There are individuals too, who deplete others of their life energy, sucking, sucking, trying to fill the empty space inside themselves. The more they suck the hungrier they are, that’s the irony of it. But for every vampire there is someone who radiates positive energy. Someone to whom others gravitate.

‘Mum,’ says my son, nudging me.

‘Most galaxies,’ I tell him, ‘have a supermassive black hole in their centre, a bit like a giant plug hole. Some of them are as big as billions of suns put together.’

His eyes are wide with wonder.

‘Is that as big as infinity?’ he asks.

‘No, infinity is bigger than anything.’

‘Like families,’ he says.

‘Families?’ I ask, puzzled, then wait while he thinks, loving the little furrow on his forehead and the faraway look in his eyes.

‘The way they go on forever, both ways. . . grandma and great grandma and us.’ He takes a breath. ‘And then we’ll have kids. . . and so will they. . .’

Slowly it’s dawning on me, the beautiful thing that my son has achieved. He’s connected space and time with infinity.

‘Yes!’ I say. ‘Yes, that’s exactly it.’

I clamour about in my memory for more wonders to feed my insatiable son.

‘As the stars and planets get closer to a blackhole they speed up, faster and faster, and time speeds up too, until a year is only twenty or thirty days. Imagine that, you’d have a birthday every few weeks.’

He laughs out loud at this but I can see his mind at work, calculating the present potential.

‘And there’s a theory that these supermassive black holes shoot out jets of matter, sometimes millions of light years long.’

‘Why?’ he asks.

‘I don’t know. Perhaps they throw up the bits they don’t want. Or maybe they recycle all the old negative energy and spit out fresh clean matter. Isn’t that a lovely thought.’

My son is quiet, he’s storing it, a special sweet to savour. He’ll want more, but I’ve reached the limits of my black hole knowledge and my daughters are waking. The stillness is being taken over by activity: lights flicking on and off, the toilet flushing, someone blowing their nose. It’s time to get up. Reluctantly I leave the warmth of my bed for the shock of a cold toilet seat. Then fumble about in the dark looking for slippers, woolly socks and a jacket. The chores are about to begin: breakfast, packed lunches, teeth, faces, clean undies, shoe laces. . . But first there’s the frosty trip outside for wood, the grass frozen solid, crunching under my feet, as I breathe steamy dragon breaths and ignore my shivering for long enough to stand staring up at the Milky Way, wondering at the universe once again after all these years of forgetting. . .

Another gift from my children.

All day

I hold them close.

About Rosie Dub

Dr Rosie Dub is a novelist (Gathering Storm and Flight), mentor, teacher, developmental editor and facilitator of Centre for Story (www.centreforstory.com), a platform for reimagining the world through story. Rosie has taught creative writing for many years in both the UK and Australia. She currently teaches on the MA in Writing program at Swinburne University in Melbourne. Rosie’s PhD research explored how purpose of story as a developmental tool. She shares her ongoing research in her Alchemy of Story workshop series and her twice monthly Alchemy of Story substack newsletter which explores how story forms us, how it frees us and how we can create our own transformational stories that help to reimagine our world. Rosie lives in Hobart, Tasmania.

Gaia Within | Choosing Care in an Unraveling World

Gaia Within | Choosing Care in an Unraveling World

Featuring the art of Jerry Sage, a contributor to Pixabay, whose collection can be found here.

“Far more satisfying than pretending to have control would be to actually exercise it.”

—Tarthang Tulku, Dimensions of Mind

As we look across a planet overwhelmed with suffering—like an overcrowded boat shedding passenger into unforgiving waves—we realize that we should never have entrusted the care of our Mother to others. Why weren’t we paying attention to her decline? How could we have forgotten that it was through her care that we first began searching for our own destiny?

Trying to learn from my mistakes, I remember times when I managed to break free from a private, lonely trajectory mired in misery and loss. Observing the world around me now, it’s clear that my distress was never mine alone.

What is coming into focus—gradually replacing an anthropocentric worldview for many of us—is the realization that our species can no longer assume a guaranteed place at the table. Having distanced ourselves from the global family, no longer acting as a caring member, we must now ask: When the future arrives, will we still be welcome? Who will walk with our world into the future?

What is coming into focus—gradually replacing an anthropocentric worldview for many of us—is the realization that our species can no longer assume a guaranteed place at the table. Having distanced ourselves from the global family, no longer acting as a caring member, we must now ask: When the future arrives, will we still be welcome? Who will walk with our world into the future?

Mother Earth has remained loyal in her care for all the beings she brings into existence, nurturing, harmonizing, and sustaining life for billions of years. Among the countless species she supports, humans are just one. In time, she will surely find a way to confront the harm we have inflicted upon her and her other offspring.

What is in question is not the survival of our world, but whether humanity will be invited along to participate. For her own survival, our Mother may have no choice but to shed us like an old snakeskin—once part of her, now a suffocating remnant of an earlier stage in her evolution.

It’s not just the scorching fires, scouring winds, flooding coastal cities, flattened homes, and all the threats to terrestrial life for which we must give account. Humanity has turned against its own future by appointing the most selfish and broken among us to lead.

Time might bring back the coral reefs and provide space for species that are not yet extinct to rebuild their populations. Forests could reclaim hillsides while birds, butterflies, and bees construct their nests and hives in their shade. But how can our species survive when we choose leaders who are blind to the living intelligence that created us—whose unbalanced minds cannot even hear the symphony of life still playing around them?

Most of us just need that symphony to continue, to carry us forward in its rhythms. How tragic that continued human participation is now in jeopardy because a minority has cast its lot with forces of indifference, destruction, and cruelty.

Before I get carried away, I need to pull myself back into a realm of hope and community.

It might truly be a blessing if a wise and benevolent being arrived from beyond our world, using their power to guide humanity back toward ways of living, communicating, and collaborating in harmony with the planet—replacing our relentless extraction of anything that can be monetized and discarded in the dust. But if such a presence exists, why has it not revealed itself?

Likewise, if Gaia could bargain directly with humanity, she might set unbreakable terms—making it impossible for industries to poison rivers while selling clean water in plastic bottles or preventing the obscenely wealthy from rewriting the rules to consolidate their power. Yet Gaia, whose vast intelligence has nurtured life’s immense diversity within her embrace, seems incapable of stooping to engage in the narrow calculations of human ambition, power, and control. Instead, she, like the rest of creation, can only bear witness as humanity dismantles its own world—and the worlds of all the beings with whom we share our place in the sun.

Does the responsibility of guiding terrestrial life safely to shore really rest on the shoulders of the good-hearted and holistically conscious among us? That hopeful vision seems adrift, lost at sea. The phrase “As above, so below” may suit a Creator God, but it falls short in describing a planetary intelligence whose neural network is woven into the fabric of the Earth itself. Gaia is neither above nor below; she is a living world, continuously evolving in the direction shaped by the collective actions of her countless interdependent beings.

I am neither alone nor exceptional in feeling powerless within a society driven by those whose destructive choices go unchecked by wisdom, compassion, poetic imagination, or the vast cosmic awareness that our species is capable of. We owe a profound debt to activists who develop alternative energy sources, cultivate healthy food, and remind us that we inhabit a sacred, living planet. Yet most of us are simply trying to move through life with kindness and awareness—even as a tsunami surges inland, threatening the heart of our shared home.

I can’t say whether my approach is anything more than a private truce with discouragement but let me share the shape it has taken.

I published a novel, Gaia Awakens, (available later this month),in which many characters strive to live with decency and care but find themselves trapped in the shadow of extractive economies, the looming threat of nuclear annihilation, the shame of human-caused mass extinctions, and the unfolding catastrophe of climate breakdown. They feel powerless to halt these forces or escape their consequences.

Among them are two alien “adjudicators” who initially see no alternative but to annihilate the human species before the ark of life is dragged under.

This fictional world became a stage on which I could play out my fears for our own. One of the characters, who took his own life—just as my son did six years ago—returns from the realm of the dead with a message for a long-lived adjudicator who has forgotten his original purpose on Earth. This emissary from the beyond knows what it is to feel like an outsider, to long for belonging.

Even if this foray into fiction does nothing else, it has allowed me to imagine a continuing life for my son.

As I continued documenting my characters’ lives, I kept hoping their fate would unfold more favorably than the trajectory I see gaining momentum in our own. Yet after my first draft, they still faced the same challenges we do—still living under the weight of a deeply entrenched system, too pervasive for well-meaning individuals to halt. My hope that I could shape my fictional world in a way that would reveal not just a solution to their crisis, but also a path for us to follow, began to feel like a delusion.

But in the next draft, something shifted. It wasn’t that the aliens devised a clever or forceful plan. It wasn’t that Gaia started selectively shaking off billionaires and oil executives, or that she somehow inspired lobbyists and politicians to act with integrity. Instead, people simply grew more confident in their care for one another—more willing and able to follow impulses not dictated by the relentless demands of business as usual.

It was as if Gaia awakened to her own power in the cosmos and began finding allies among the human species. Gradually, others noticed this shift and began to join in, showing up as their better selves—grateful that they no longer had to lurk in the shadows, feeling helpless, isolated, and invisible. As this collaboration between individuals and their living world took hold, corrupt leaders found themselves with fewer and fewer followers.

A part of me wonders if the helplessness I’ve been feeling is the real delusion. There are, without a doubt, those who seek to control the world for their own ends. But if we choose to live with care, supporting the courageous actions of those around us, then Gaia will embrace us as she awakens to her place in the vast cosmos—a greater realm where she has always been a cherished and beloved daughter.

Return to the table-of-contents for this Issue, Beyond Conditioned Thinking

About Michael Gray

Michael Gray is the author of The Flying Caterpillar, a memoir, and the novels Asleep at the Wheel of Time, about whales, aliens, and humans, and Falling on the Bright Side, about his experience working with the disabled, and Winter Came Early: Reflections on outliving my son“, about his beloved son Jon who ended his life in 2019 at the age of 27. He is the cofounder of Friends in Time (a nonprofit he founded with a friend who has ALS), and past board president of New Mexico Parkinson’s Coalition and Pathways Academy (a school for kids with autism and other learning issues). A regular contributor to various journals, Gray also writes a weekly blog on www.michaelgrayauthor.com.

Composting Grief | Co-healing with the Earth

Composting Grief | Co-healing with the Earth

Featured photo | by Joshua Hoehne

Grief reminds us that, in the divine alchemy of transformation, things sometimes appear to go backwards as they move forward.

The rewilding of humanity and our genetic transformation is contingent on the way we handle grief. Grief can be felt as a loss of species, ecosystems, and meaningful landscapes due to an environmental lesion. It constantly shifts and changes, varying from person to person at different stages of life. Grief is a separate political system, indifferent to Left or Right ideologies and solely focused on consciousness.

All levels of consciousness are affected by grief, whether it is emotional or mental, ancestral or generational, ecological or cellular. A grief-related thought can alter our sound, vibration, and even the functioning of our DNA. While grief cannot be contained or fixed, we can learn to walk alongside it with strength, calmness, and order.

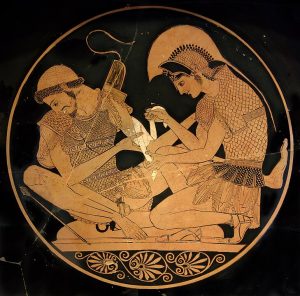

Grief | Ally and Divine Force

Works of ancient Greek literature explore grief as a divine force. In Homer’s Iliad, one universal right is the memorial. In the Trojan War, silver coins were placed at burial sites of fallen soldiers as tokens to remember the lives that were sacrificed in service of a shared civic mission. At the end of the story, the physical tokens were replaced by mourning and shaped stories: a combination of totemism and ceremonialism. The narrative is repeated in Sophocles’ “Antigone” and Euripides’s “The Suppliants,” which encapsulate the perspective that grief is a divinely sanctioned right. As a metaphorical guide , memories of the past continue to accompany our way through life and lead us to the future. There is still a delicate balance in the way we treat our grief and memories of our ancestors and creation.

The key is in recognizing how profoundly our thoughts can shift our genetic state. We have an aptitude to evolve without waiting hundreds or thousands of years.

I believe the human body is capable of communicating through signals of sound, hormones, and photons to itself and its surroundings, including underground ecology—the Earth.

A Grief Ecosystem

Nature’s medicine lies in the ground. The soil is the dust, blood, flesh, and bones of our ancestors as much as it is a part of our own being and waking experiences. It is so present in molecules of air and food that we miss it entirely. The soil connects all of the pieces together, in a sense, the way grief does. It Grief is the intimate fabric of connection with the natural world. Humans belong to the land just like any animal, plant, mineral, water, and air particle, and each being experiences the emotional, spiritual, mental, and physical fertility of the ground.

The concept of “composting grief’’ resonates as a way of transforming energy into a renewed sense of purpose and growth. I think of this as transmutation or snake medicine: sound, meditation, selfless service, praying, nature, movement. I propose that we explore the concept of a symbiotic relationship between human grief and its impact on the underground microbial life—the microbiome—through a multidisciplinary approach that encompasses scientific, physiological, and ethereal aspects of meditation.

Similar to composting, I believe a human being is capable of cognitively and physiologically transferring ionic energy containing grief information into the Earth through conscious meditation and grounding techniques. What has been referred to as “grounding,” or simply placing your bare feet on the Earth’s surface, reduces cortisol levels, inflammation, and calms the nervous system through the absorption of the ground’s negative ions.

The soil contains various bacteria that absorb and masterfully manipulate electrons and ions in their environment. In meditation, we intentionally release feelings of hurt, worry, and fear, guiding our thoughts to calmness. Breathwork further enhances this process by encouraging awareness and presence within each cell, helping to alleviate anxiety and welcoming openness to new possibilities. Using the same vibration-driven principles present in grounding, meditation, and breathwork, a person reconnects with their inner self and facilitates an energetic exchange of grief with the soil, fostering personal healing and evolution.

The soil is a network of life-giving microorganisms, akin to the mitochondrial membrane potential in our cells, that support the vital bioenergetics of the underground mystery. Actinomycetes, fungi, bacteria, nematodes, earthworms, whiteworms, millipedes, flies, land snails, and beetle mites are first-level consumers of compost.2 This layer supports the rest of the underground microbiome—protozoa, rotifera, soil flatworms, predatory mites, ants, rove beetles, feather-winged beetles, ground beetles, mold mites, springtails, pseudoscorpions, centipedes, and other undiscovered species.3 All of these organisms support the existence of higher tropic life forms. They date back nearly four billion years and will probably survive any future extinction event.

This diverse soil microbiome mirrors our body’s repair system. Whenever a cell exhibits harmful effects on its genetic material, such as mitochondrial oxidative stress, DNA fragmentation, alteration of gene expression, or genetic mutations, T cells are recruited to mount an immune response. T cells work together with glial and neuron cells to regulate the damaged cells’ microenvironment: glial cells are insulation and nutrition; neurons carry messages and meanings. Grief is cached inherently within the memory of T cells and turned into a passage of intergenerational information. T cells can be likened to soil microbes that repair soil health through nitrogen fixation and suppression of pathogens.

As we’ve seen, bacteria are an important component of the soil microbiome. Bacteria aren’t solitary organisms. They exist on everything and are deeply embedded in the human DNA construct. They use a cohabiting language of electrical signaling to other bacterial forms for their survival. This mode of communication between humans and bacteria isn’t fundamentally different from the language between humans and water, or humans to humans. It is as real as channeling, meditating, or talking with a loved one.

A book, Grounded: A Fierce, Feminine Guide to Connecting with the Soil and Healing from the Ground Up, by Erin McMorrow was sent to me as a surprise gift by my friend, Maggie Kennedy, who said she felt would resonate with me. Not only did it resonate with me, but it turned out that this book on sacred interconnectedness activated my own path of regenerative healing through writing. So, I became a writing student under Dr. McMorrow’s guidance.

“Composting is a form of giving back to Mother Nature and the cycles of nourishment,” Dr. McMorrow says, “and it’s also a reminder that the things we think we can’t use can actually be returned to the earth with care and used for something else (the material version of releasing any energy from our bodies that doesn’t serve us).”1 Human and soil microbiome share an inherent quality: both are in a constant state of repurposing energy to regenerate life: “grounding” and “earthing.” Studies have yet to explore the proliferating impact the human body has directly on the soil through meditation because it’s immeasurable. One can only trust, believe, and commit to doing it to experience the results. By prayer, mantra, or meditation, human beings can create a meaningful relationship with soil.”

In 2020, one of the first studies examining the impact of meditation on gut bacteria, which are crucial to overall health, compared bacterial responses between study participants who meditated and those who did not. The results showed three types of bacteria—Bifidobacterium, Roseburia, and Subdoligranulum—responded to the brain’s influence and led to a series of changes in the intestinal flora that improved the body’s holistic regulation. These changes included enhanced cellular motility and stronger immunity.

Meditation activates the gut-brain axis (GBA), an increasingly discussed topic in the last decade. The GBA is a bidirectional communication network between the central nervous system, autonomic nervous system, and the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA). The gut-brain axis integrates gut function with emotional and cognitive centers in the brain. A 2021 study on meditation and gut microbiota proposed that meditation can reinforce healthy gut-brain axis* crosstalk through the central nervous system (CNS) and ANS pathways.4

While conventional science emphasizes the role of the gut microbiome influencing our emotional well-being, my inquiry on the axis between meditation, emotions, and soil ecology is yet to be systematically explored: The study on the effect of meditation on intestinal flora hints at a possible connection between emotional well-being, as fostered through practices like meditation, and the broader ecological systems that surround us.

The suggested link between meditation and the underground microbiome—composting grief—draws upon the relationships among cyclic meditation, the microbiome, the gut-brain-axis, esoteric teachings, and various healing practices.

A 2022 study by Maeder and colleagues used acoustic “soundscapes” to predict temporal and spatial dynamics† of organisms in the soil.6 Although soundscapes are more commonly researched above the ground, the results of the study suggest that the acoustic diversity can be calculated from different soil communities. The evident differences between soil soundscapes can provide insights into the soil’s composition (such as taxa richness) and help evaluate the relationships between living soil microorganisms with greater precision. In a similar manner, we could apply eco-acoustic technology and statistical methods to observe the impact of grief meditation and sound as a noninvasive approach to monitoring “soil ecology” in the composting grief process. Grief reminds us that, in the divine alchemy of transformation, things sometimes appear to go backward as they move forward. Through our shared experiences of grief, both we as individuals and the planet can evolve together.

In the next section, we will explore a meditation technique that combines the elements of soil and sound to facilitate the transmutation of grief. Feel free to immerse yourself in this process and trust your instincts, as healing is an organic and unique journey for each individual.

Composting Grief Meditation

Start by putting both feet on the ground, or visualizing the feet in the soil. You could close your eyes and see roots from your tailbone lowering into the ground, physically connecting with the land. Think of gratitude for the soil and its underworld microorganisms.

Thank you, Mother Earth, for sustaining our bodies and spirit with the sacred spirits of water that I return back to the land, rivers, and streams with gratitude.

Call on your divine guides, ancestors, and angels.

Reflect on the grief that you would like to compost: fear, loss, shame, jealousy, anger/rage, anxiety, depression, hopelessness, confusion, discomfort, chaos, hate, and discord—stressors that can be associated with grief and trauma. Form them into a shape. Take an inhale, and with the exhale, move the shape in a downstream pattern through your perineum, legs, and feet into the ground, like tree roots. Repeat with each inhale.

This motion creates a downward spiral, shifting laterally to cycle upward. The “down” cycle represents the grief that will be energetically decomposed by the underground microbiome to give life; the “up” cycle is the oxygenated life that is created by the microorganisms and absorption of the ionic charge from the ground. This circular scheme is stimulating a cellular connection between the human body and the underground microbiome. Its biochemical symbiosis will enrich the acidity, moisture, and oxygen to allow decomposition slowly over time with safe byproduct levels of carbon dioxide. It is earthing for you, composting grief for the fertility of the soil and the garden of your life.

You can stay in this meditation for as long as you feel comfortable. Gratitude is the portal through which your emotions continually filter through as they penetrate the ground through the biochemical channel of your chakras. When you are ready to end the meditation, take a moment to express appreciation to the land and your guides.

Placing your hand on the ground is a way of relaying the ground’s sensitivity to the brain. The ground will share information to you in multiple ways, whether through its vegetation, animal attraction, or the vibration that the ground connects with you on a cognitive level. Consistency enhances your body’s connection with the ground, fostering a sense of restoration and prolificacy. Remember, this practice aims to support your healing journey, as grief is not something to be fixed but a process to be navigated with compassion and understanding.

As our understanding of the interconnectedness of life and its adaptability continues to grow, we can explore intuitive nutrition, elemental sounds, and effective fertilizing techniques to nurture a symbiotic relationship with grief. This knowledge helps us to shift our perspective on grief’s role in our lives. As we learn more about bacterial intelligence and its impact on consciousness, evolution, and cognition, we open gateways to new approaches of connecting with our bodies, caring for the land, and pursuing a path of mindful individuation.

†Spatial dynamics is the study of the relationship between an entity and its surrounding environment, and as a result, temporal dynamics is the observation of the inherent complex changes to the entity’s behavior over time.

References

- McMorrow, Erin. Grounded: A Fierce, Feminine Guide to Connecting with the Soil and Healing from the Ground Up. Louisville, Colorado: Sounds True, 2021.

- “All the Compost Creatures: Levels 1, 2 and 3.” Planet Natural Research Center. December 8, 2022.

- “All the Compost Creatures: Levels 1, 2 and 3.” Planet Natural Research Center. December 8, 2022.

- Ningthoujam D. S., N. Singh, and S. Mukherjee. “Possible Roles of Cyclic Meditation in Regulation of the Gut-Brain Axis.” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (2021): 768031.

- Alonso et al., “Maladaptive Intestinal,” 163–72; Alvery et al., “Gut- Derived,” 480–89; Cogan et al., “Norepinephrine,” 1060–65; Freestone et al., “Involvement of Enterobactin,” 39–43.

- Maeder M., X. Guo, F. Neff, Mathis D. Schneider, and M. M. Gossner. “Temporal and Spatial Dynamics in Soil Acoustics and Their Relation to Soil Animal Diversity.” Plos One 17 (2022): e0263618.

About Ruslana Remennikova

Ruslana Remennikova is a former research scientist for the Fortune 100-ranked company ThermoFisher Scientific where she worked with vaccine sciences. In a 2016 leap of faith for a more meaningful life, she left the world of corporate science to later open a sound medicine practice while writing her first book, Activating Our 12-Stranded DNA: Secrets of Dodecahedral DNA for Completing Our Human Evolution. She is the founder of Songbird Science, a research company exploring frequency and consciousness. Born in Ukraine, she currently resides in central Virginia.

Amid the Darkness | Human Kindness in Gaza

Amid the Darkness | Human Kindness in Gaza

I keep looking at my people, and perhaps the greatest blessing throughout the entire calamity being visited upon us is that we constantly urge each other to remain tender toward one another.

With all of the violence, pain, and suffering we are living through, we are angry, anxious, and on edge all the time. It is a constant struggle to remain sane, continue to live by our values, and to treat each other gently. But we keep finding energy where none is left.

This is where perhaps the Israeli regime is right: We are all fighters in Gaza, in Palestine. We are all fighters because we dare to maintain our humanity. This is the battle unspoken, the one we are taking on with nothing but heart and starved bodies, surviving bomb after bullet, and bullet after bomb.

We are indeed fighters, warriors, and the population that keeps rising up. The banality of our struggle is missed in how the world sees us: We are not merely victims of Israel’s ruthless wrath; we are the ones directly resisting even if that resistance does not look like what you think.

Standing together

During these taxing and laborious times, I learned the layers of what it means to have a family, to be a human, and to support each other selflessly.

When Israel targeted Gaza as a whole, it was doing something even more sinister than taking lives and destroying buildings. It was attempting to destroy the intangible things that bind us together. This is the strategy of colonial armies and regimes – to divide and conquer.

Israel wasn’t trying to slaughter us all. It will always preserve parts of the population simply so it can say, “We didn’t eradicate them, see?”.

But what Israel’s administration is doing – at least trying to do – is to transform the kinship and safety we feel with each other; to pit us against each other, make us resentful towards one another, and engineer a population that directs its rage and frustration inward. What Israel, and all of its allies, cannot understand, comprehend, or recognise is that at every moment we do the exact opposite.

They have cut off aid trucks from entering the Gaza Strip, blocking us from accessing our money, and causing the prices of even the most basic items to rise unbelievably high. But we have stood together from the beginning. It is true some people have become selfish, thinking only of themselves. But others have done everything they can to split the limited amount of food that we have – even when it is the only food they have for their children – and share it with others.

Family and survival

What we are surviving in Gaza is not just the ferocity of Israel’s lethal weapons; it is also the mental exhaustion, emotional dysregulation, and depletion of hope and faith that the past year has brought. I believe Israel is doing this so that if they ever decide to give us a real opportunity to negotiate, we will seek the bare minimum.

After all, we are made of flesh, bone, heart, and soul – all fragile components of our human composition; all of which require constant taking care of, and all capable of becoming rotten. The only thing saving us, is us. The family battalion is the battalion that is fighting one of the hardest battles.

Before the war, my family wasn’t rich, but I lived a life most girls dream of. I had the luxury of a home, a higher education, and the finest material to paint. I am an oil painter, and I used to paint on canvas. I miss it more than I ever imagined. Of course, we couldn’t afford every single thing I desired, but I was content and grateful. Now, I see my father during this war struggling just to keep us alive.

Israel has made it so we can’t access the money in our bank accounts, and my father has no way of making a living. Still, he has been trying his best to provide us what we need. Even when he can’t, he selflessly offers us the little bit of food we have even if it means he will have to go without, preferring to provide for our needs over his own.

Long-Term Environmental Consequences

The environmental impacts of the war in Gaza are unprecedented, according to a preliminary assessment by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), exposing the community to rapidly growing soil, water and air pollution and risks of irreversible damage to its natural ecosystems. UNEP reiterates the call for an immediate ceasefire to protect lives and eventually help mitigate the conflict’s environmental impacts.

“Not only are the people of Gaza dealing with untold suffering from the ongoing war, the significant and growing environmental damage in Gaza risks locking its people into a painful, long recovery. …Water and sanitation have collapsed. Critical infrastructure continues to be decimated. Coastal areas, soil and ecosystems have been severely impacted. All of this is deeply harming people’s health, food security and Gaza’s resilience,” said Inger Andersen, UNEP Executive Director.

The preliminary assessment finds:

- The conflict undoes progress on Gaza’s environmental management systems, including development of water desalination and wastewater treatment facilities, a rapid growth in solar power, and investments in the restoration of the Wadi Gaza coastal wetland.

- An estimated 39 million tonnes of debris have been generated by the conflict – for each square metre in the Gaza Strip, there is now over 107 kg of debris. This is more than five times the quantity of debris generated from the 2017 conflict in Mosul, Iraq. Debris poses risks to human health and the environment, from dust and contamination with unexploded ordnance, asbestos, industrial and medical waste, and other hazardous substances.

- The water, sanitation, and hygiene systems are almost entirely defunct. Gaza’s five wastewater treatment plants have shut down, with sewage contaminating beaches, coastal waters, soil, and freshwater with a host of pathogens, nutrients, microplastics, and hazardous chemicals. This poses immediate and long-term threats to the health of Gazans, marine life, and arable lands.

- The solid waste management system is severely damaged. Five out of six solid waste management facilities in Gaza are damaged. By November 2023, 1,200 tonnes of rubbish were accumulating daily around camps and shelters. A shortage of cooking gas has forced families to burn wood, plastic and waste instead, endangering women and children in particular. This, coupled with fires and burning fuels, is likely to have sharply lowered Gaza’s air quality, though no open-source air quality data is available for Gaza.

- Munitions containing heavy metals and explosive chemicals have been deployed in Gaza’s densely populated areas, contaminating soil and water sources, and posing a risk to human health which will persist long after the cessation of hostilities. Unexploded ordnance poses especially serious risks to children.

- Destruction of solar panels is expected to leak lead and other heavy metals, causing a new kind of risk to Gaza’s soil and water.

Limited by the security situation and access restrictions, the preliminary assessment is informed by remote sensing assessments, data from Palestinian technical entities, consultations with multilateral partners, previously unpublished material from UN field-based activity, and scientific literature.

Source | UNEP

A Child’s Life in Gaza, Photos by Hosny Salah

Pulling me through

At times I have reached rock bottom, I have lost hope, I have thought, “This is the end”. I only just turned 22, and I have believed that I will die displaced, that I will be blown into pieces and no one would be able to recognise my features, that I will die hungry without being able to fulfil even my smallest desires – to eat a meal in my home again and live until I get married and have a family of my own, to die after a long, happy life surrounded by the people I love.

When this happens, amid all the darkness that only seems to get darker, the only thing that pulls me through is my family.

My family was forced to flee on 7 October last year from our home in al-Tuffah, a neighbourhood in the historic centre of Gaza City that has existed since the 13th century.

My brother, who lives in Deir al-Balah, in the centre of the Gaza Strip, took our whole family under his roof. Thank God, we have not been forced to evacuate again. But we are always afraid. His home is next to a hospital, and hospitals have frequently been targeted by the Israeli military. We did have to escape once, when they bombed the mosque next to the house, but we were able to return.

He crammed his own family – his two daughters and two sons – into one room just to give the rest of us some space to feel comfortable. This is family; this is coming through despite the scarcity of resources, despite the density of breaths in a single room, despite the bombs around us, despite it all.

With me, my parents, sisters, and brothers, and their spouses and children, and my uncle and his family – there were a lot of us to take in. Twenty-eight people in one house. But my brother tried to make us feel safe during the most horrifying nights. At a bare minimum, he tried to make us feel we were still at home.

Two extremes

During winter months, we shared blankets and hugs. When we woke up cold at night, terrified by the artillery bombardments, we had each other. We gave each other strength and patience. We shared food at the same table. We played cards late at night to ease the long cold nights.

I remember my sister-in-law. She was pregnant, and she got sick. You know how painful that can be. A pregnant woman is vulnerable and weak already. She was so worried, and it was a freezing winter night. My uncle’s wife woke up in the middle of the night and made her a warm soup. I know you might think it is nothing, but it was everything she needed to heal.

When I had a fever – a very painful one – I remember my body wouldn’t stop shivering under a lot of blankets. My mother stayed there holding me in her embrace. I thought I was going to die. My face was so red, like it was on fire. I remember the whole house was there for me, asking me if I needed anything.

I couldn’t help but wonder, “How can there be two extremes in the world: humane and inhumane?” Some people fight to do whatever it takes to help each other ease the pain; others keep proving that they have no problem inflicting it.

I don’t exactly know what was wrong with me. I had a bad fever, and my body could not stop shaking. There are so many sick people. There have been huge outbreaks of disease, especially among children. It is impossible to find medicine, and if you manage to find some it is really expensive. There is only one clinic in our area to respond to all of this. It is a struggle to get an appointment – I never got one. Luckily, I survived.

These are the things

One day, I was sitting by the beach with my bare feet on the shore. I was really devastated. Miserable. I could not help but cry. A little girl sat by my side. She was very beautiful. Her hair was bleached from the heat of the sun, her skin burnt, and she was asking for money. I had none at that moment to give her.

When she saw me crying, she sat by me and asked me to play with her in the sand. So we played and made a little castle. She managed to make me laugh, and kissed me on the cheek.

Later, as I was walking down the dead streets, I saw a man selling bananas. I was craving any fruit, especially bananas, as they remind me of home. I used to love eating one every morning before heading to my university. I asked the man how much one cost. The man told me a very high price that I couldn’t afford. I kept walking, but he called after me and offered me a banana for free.

I ate the banana with tears in my eyes. It tasted like heaven to me because it reminded me of home.

These are the things I will be grateful for until the day I die: A kiss on the cheek from a barefoot child on the burning sand; the man who gave me a banana for free because he knew I was craving one and didn’t have the money to pay for it; the people who have been there for me by my side; the people who have opened their homes to their displaced brothers and sisters, and those who share their food and their children’s food with others.

I am grateful to every single human who has kept their humanity despite the horrifying violence we live in every day.

–––––

The New Humanitarian puts quality, independent journalism at the service of the millions of people affected by humanitarian crises around the world. Find out more at www.thenewhumanitarian.org.

Haiti's 'Sin' of Resistance

Haiti’s ‘Sin’ of Resistance

Featured image | by TopSphere Media

Background

Haiti is experiencing a multifaceted crisis marked by severe gang violence and significant economic and social challenges for its people. Despite international interventions, such as the Multinational Security Support mission headed by Kenya, the strategy has been hindered by unclear goals, lack of accountability, and inadequate backing for Haitian institutions. Additional issues include a shortage of armored vehicles, helicopters for medical evacuations, prepared barracks, and proper communications equipment. This mission, which received UN Security Council approval last October, has faced considerable opposition in both Haiti and Kenya.

Many of the tragedies befalling the island nation trace back to colonial interventions

Years ago before I began teaching, I became friendly with a maintenance crew member on the job. He was a brotha, but what connected us was our shared religious beliefs. We would engage in water cooler talk about faith, sports, the weather, and current events.

Before his departure, we had a conversation in early 2010 lamenting the situation in Haiti. The nation had just experienced a devastating earthquake, killing hundreds of thousands of people. I commented on my hope for recovery and peace in the land. He responded by saying that Haiti has a history of heartache and devastation, and the reason for that is due to the nation’s sin.

I asked him to elaborate.

He said that because, historically, there has always been a contingent of Haitians who practice voodoo and, as a result, they were being punished by the creator. I tried to explain to him why he was wrong.

First, I told him that what he called voodoo is a diasporic fusion of traditional African faith systems and Catholicism (used, in some cases, as a form of resistance to Catholicism); second, that most Haitians were Christians; and lastly, that the circumstances plaguing the Haitian people were the fault of the French as well as the United States, both of which punished the nation for liberating itself from colonial rule.

If sin is the culprit for Haitians’ suffering, it is the sin of the colonizers, not the resisters. Saying these things is the reason this brotha stopped speaking to me.

I was saddened, not only because what I thought to be a developing friendship suddenly ceased, but because I was afraid that more Black people thought like this—that Haiti was to blame for its condition. Whether one pinned the blame on gang violence, a multiplicity of religions, or corruption in the government, Haiti was at fault for its own plight.

As Frederick Douglass said of Haiti in 1893, “Haiti is Black, and we have not yet forgiven Haiti for being Black or forgiven the Almighty for making her Black.” And today, the West still has not forgiven the descendants of the Haitian revolutionaries for showing the world the first truly free nation in the hemisphere.

Numerous reports and pictures of what’s happening in Haiti would have one believe that the Haitian people are incapable of running their own country and that an intervention from the “international community” is necessary. However, clarity comes by way of understanding history; history explains why, as Douglass said, Haiti has not yet been forgiven.

Crisis in Haiti

- The UN reports that gang violence has killed 2,500 people this year alone.

- Widespread poverty: Even before the current crisis escalated, Haiti, ranked by the World Bank as the most impoverished nation in Latin America and the Caribbean region, struggled with economic challenges that deeply impacted its people’s daily lives.

- Food insecurity: Haiti teeters on the brink of a hunger crisis, with acute hunger affecting more than 4.3 million people, nearly half of the Haitian population, according to the World Food Programme (WFP). Additionally, 1.4 million people face emergency levels of hunger.

- Displacement: Ongoing conflicts and natural disasters have displaced approximately 362,000 people within the country.

- Healthcare crisis: The upheaval in late February has pushed Haiti’s health system to the brink of collapse. Violence has forced the closure of three major hospitals, while armed attacks and shortages of medicine and staff have led to scaling back or the shutdown of many health centers.

- Gender-based violence: Women and girls bear the brunt of the escalating violence, as gang activity has further increased gender-based violence.

Source | https://www.worldvision.org

Historical Context

The island was originally named Ayiti by the Taino who inhabited Hispaniola. When the French arrived there in the seventeenth century, centuries of disease from European invaders had already wiped out much of the Indigenous population. With the land, the French created sugar and coffee plantations and kidnapped Africans to serve as the labor force. They kidnapped so many Africans that eventually enslaved people vastly outnumbered the French. Chattel enslavement—where people were legally regarded as property—was brutal on the island. As a result, resistance was rampant.

Maroon communities soon developed on the island. Inspired by the French Revolution of 1789, Africans undertook their own revolution beginning in 1791. Pierre Dominic Toussaint—later named Toussaint L’Ouverture—led the battle for independence, driving Napoleon mad with disdain. L’Ouverture’s capture notwithstanding, Africans achieved victory and declared independence from France on January 1, 1804, under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

After achieving independence from France, there was no “happily ever after” for the Africans of the former colony of Saint Domingue. The French responded with a choice for the Africans: pay reparations to the French enslavers or fight another war. In July of 1825, Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer chose the former. The Haitians owed more than 150 million francs. Haiti didn’t have the money to pay the debt, so they were coerced by the French to borrow from French banks to pay it.

This is known as the double debt. According to The New York Times, Haitians paid about $560 million in today’s dollars, which could have added $21 billion to the Haitian economy over time.

These are funds that could have built the nation. Instead, they went to further build up France. As Haiti finished its repayment, the French hijacked Haiti’s treasury, establishing the Haitian National Bank in Paris under the control of French financiers. The Haitians believed that the move would bring investment in the country. But it only continued to weaken Haiti’s economy.

Next came the United States, beginning with an operation in 1914 where the Marines walked out of Haiti’s national bank with $500,000 in gold destined for Wall Street. Citing the Monroe Doctrine, which framed any foreign intervention in the Americas as a threat, the United States launched a full-scale invasion and occupation of Haiti in response to German inroads into the Haitian economy. Racist ideas stoked by the media—like the notion that “some of the highest officials of Haiti took part in the cannibalistic rites of voodoo”—provided cover for the campaign.

Maybe that’s where my “friend” got his ideas from, but I digress.

Dollar diplomacy—loan disbursements overseen by American financiers coupled with a twenty-year military presence—was the mechanism for the U.S. occupation and the increase in wealth of American banks, including Citigroup, formerly the National City Bank of New York. Haiti, as well as the Dominican Republic, became “friendly” to foreign (American) investors. According to The New York Times, the United States did so by:

“Dissolving Haiti’s parliament at gunpoint, killing thousands of people, controlling its finances for more than thirty years, shipping a big portion of its earnings to bankers in New York, and leaving behind a country so poor that the farmers who helped generate the profits often lived on a diet ‘close to starvation level.’”

Following colonial rule was the nearly thirty-year dictatorial reign of Francois and Jean-Claude Duvalier, who had the support of the United States. With that support, Papa Doc, Baby Doc, and the Duvalier syndicate of family and insiders stole millions of dollars from the country. The years of non-investment in the nation’s agriculture and infrastructure yielded poverty, malnutrition, and illiteracy for much of Haiti’s population.

In 1990, Catholic priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide, an advocate of liberation theology, was elected President, with 76 percent of the vote, campaigning on the social, economic, and political empowerment of the poor while reforming institutions like the military—much to the dismay of the economic elite and the military itself. He lasted only nine months due to a military coup, assisted by a CIA discrediting campaign. He was reinstalled in 1994 with limited power per negotiations with the United States.

Aristide returned to power in 2001 as the elected president with 92 percent of the vote. But the international community wanted him out. The Ottawa Initiative on Haiti was held in Canada in early 2003, when the United States, France, and Canada decided to remove Aristide again. A few weeks later, on the 200th anniversary of Toussaint L’Ouverture’s death, Aristide demanded that France pay the island nation the $21,685,135,571 that had been extorted as part of the double debt.

In response, the Haitian elite funded an armed resistance and the United States equipped them with weapons. One of its leaders, Guy Philippe, was trained by U.S. special forces in the Dominican Republic and legitimized by Western media. Another insurgent leader was Andre Apaid, who led the Group of 184. He was supported by the International Republican Institute (IRI)—an organization funded by the U.S. State Department.

The coup d’état to remove President Aristide took place in February 2004. The campaign was driven by Philippe and Louis Jodel Chamblain, the former head of a rightwing paramilitary group responsible for countless atrocities under the military junta that ruled Haiti from 1991 to 1994. Like Philippe, Chamblain was also trained in the Dominican Republic.

On February 29, 2004, President Aristide and his family were removed from power. U.S. and French officials claimed that Aristide’s autocratic turn, and not his call for reparations, precipitated their regime change goals. According to Thierry Burkard, French ambassador to Haiti at the time of Aristide’s ouster, however, his removal was “probably a bit about” the call for reparations. Additionally, Aristide’s governance suffered from instability and a lack of security.

Since Aristide’s removal, the United States, France, and the United Nations’ Stabilization Mission in Haiti have played a large role in the nation’s political affairs. In 2019, Congress passed the Global Fragility Act (GFA) as a policy to justify future invasions and occupations in the name of preventing Russia and China from extending their influence.

The first nation to be selected for intervention was Haiti. This choice was made to prevent Haiti from establishing diplomatic ties with China and Russia and therefore preventing their access to Haiti’s natural resources. A notable endorser of the GFA was Georges Fauriol, a senior associate for the Center for Strategic and International Studies and one of the IRI strategists who had helped overthrow President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004.

The GFA comes with a ten-year plan where U.S. government agencies work “in a more strategic, unified, and locally-led fashion to address the underlying causes of conflict and insecurity while working with partners to prevent or mitigate the impact of future crises.” Exacerbating the “need” for intervention was the assassination of then-president Jovenel Moïse in July of 2021 and a devastating hurricane one month later.

The Biden Administration pledged that the GFA will use the United Nations and “other multilateral organizations” to carry out its missions. With that, the United States and Ecuador introduced a U.N. resolution for a multinational force in Haiti that was approved placing Kenya at the lead. The Core Group of ambassadors designated by the United Nations (from the United States, France, Canada, Germany, Brazil, Spain, and the European Union) declared Ariel Henry the new Prime Minister and leader of the nation, although an interim prime minister was already in place leading the country. Henry’s tenure, considered corrupt by most Haitians, ended in 2024 with his resignation at the behest of armed gangs who threatened civil war had he remained.

The current chaos in Haiti is blamed on a succession of poorly managed governments that have engaged in political corruption and economic mismanagement, and thus failed to provide Haitians with essential services. Mainstream media in the United States reinforce this narrative with pictures and videos on their platforms of gang violence, poverty, and a beleaguered police force.

But the chaos is the fault of the United States, France, and the rest of the international community—whom Henry called upon as soon as he came to power. Paramilitary gang violence painted as the root of the instability can be traced back to the Duvalier era. The gangs today are sustained by the interests of a small political and economic elite in Haiti, which are connected to foreign interests.

Since Haiti sought to establish itself, Western powers have worked to not only exploit the country but paralyze it from becoming a sustainable power. Because of the impact of the double debt, the United States can justify its interventions due to the conditions of the country—which are a direct result of money and resources fleeced by France. But the language used ignores this double debt.

The truth is that Haiti’s recent succession of leaders—Latortue, Martelly, Moïse, and Henry—were all approved or directly selected by the U.S. government; that Haiti is under a twenty-year occupation by the United States and the international community; and that it doesn’t look like it’s going to change. Intervention has only incapacitated Haiti and more intervention will do the same.

When Aristide made the call for reparations from the French in 2003, in attendance was the French ambassador to Haiti at the time, Yves Gaudeul. Speaking at the time, Gauduel admitted that France was “very disdainful of Haiti.” He continued, “What I think we will never forgive Haiti for, deep down, is that it is the country that beat us.” What Gaudeul left out was that Haiti was Black and that in the West, Black people defeating the white power structure is unforgivable.

The history of Haiti since is a history of the West never forgiving and never forgetting. My former friend believed that the Haitians were punished for their sins by the creator. When is the time the French and U.S. are held accountable for theirs against Haiti?

***

The main body of this article originally appeared in The Progressive, May 25, 2024 and is reprinted with their kind permission.

Since 1909, The Progressive has aimed to amplify voices of dissent and those under-represented in the mainstream, with a goal of championing grassroots progressive politics. Their bedrock values are nonviolence and freedom of speech.

Return to Volume 24 Issue 4, Collective Mind of Peace

About Rann Miller

Rann Miller is an educator and freelance writer based in New Jersey. His Urban Education Mixtape blog supports urban educators and parents of children attending urban schools. He is the author of the recently released book, Resistance Stories from Black History for Kids (Bloom Books for Young Readers, March 2023). Follow Rann on Twitter @RealRannMiller

Earth Hospice

Earth Hospice

“Unfortunately, there’s a lot more where that came from,” says Mike as we gather another armload of ash logs from the back of his truck and carry them into my shed. Mike and his family live in a log cabin on ten acres of woodland composed mostly of white pine and ash, and the ash is dying.

“I know,” I say as I stack the firewood on the growing pile. “It’s so sad.” An insect that probably hitched a ride to the U.S. from Russia in a wooden packing crate about thirty years ago is decimating ash trees across more than thirty-five states and five Canadian provinces. The emerald ash borer is a showy creature, with a sparkling green back and a scarlet belly, but its glamourous appearance belies a monstrous appetite, and it has already killed more than fifteen million trees.

Mike picks up one of the logs and draws his finger over the wheat-colored wood. “Here, you can see the tracks they make.”

Like a ribbon of toothpaste unfurled by a toddler engrossed in a stealthy experiment, the pale white trails loop and wind through the cambium. It is this tissue just under the bark that draws water and nutrients through the tree; by eating their way through it, the beetles slowly interrupt the vascular system, and the tree dies. The emerald ash borer, or EAB, is aided in its march through North America’s forests by climate change, for fewer very cold days give it more opportunity to keep flying on to new and tasty locations.

We both fall into the silence of helplessness.

“So,” says Mike, trying to put a positive spin on the conversation, “just let me know if you need more.”

Climate change, a fairly benevolent term on the surface, is seeded by heat. However, despite one cheery report I heard on the radio a couple of decades ago, this is not the simply kind of heat that could make it possible for vineyards to flourish in Maine. Climate change brings heat that spawns calamitous reactions in multiple directions, each of which spawns new problems. It is a fearsome process and one that will go on expanding, shattering, and rearranging until, finally, the world ceases to pump excessive carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Climate change itself is the biggest invasive beast in human history.

The bravest among us despair, even as they resolve to buy local foods and electric cars, plant pollinator gardens, and refrain from getting on planes. The more timid console themselves by evoking hope and an abiding belief that God or scientific ingenuity will somehow yank us out of the boiling pot at the last minute. However, the chance that the nations of the world will, without delay, take the steps required to reduce carbon emissions radically enough to prevent the most devastating effects of climate change looks unlikely. Scientists now say we will probably not be able to prevent the temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the goal set at the 2015 climate summit in Paris.

We must take a deep collective breath and say, Yes, the Earth as I know it is dying.

***