Tending the Wild

This section is named after a book by Kat Anderson that describes the relationship between the pre-colonial indigenous people of California and the land. Anderson demolishes the myth that hunter-gatherer people were mere occupants of pristine “nature,” demonstrating their deliberate, sustained influence on the composition of biotopes and species in their territory. Entire landscapes that appeared to the untrained eye of white settlers as wild were anything but. Anderson explains:

Through coppicing, pruning, harrowing, sowing, weeding, burning, digging, thinning, and selective harvesting, they encouraged desired characteristics of individual plants, increased populations of useful plants, and altered the structures and compositions of plant communities. Regular burning of many types of vegetation across the state created better habitat for game, eliminated brush, minimized potential for catastrophic fires, and encouraged diversity of food crops. These harvest and management practices, on the whole, allowed for sustainable harvest of plants over centuries and possibly thousands of years.21

When white settlers marveled at the stupendous bounty of fish, game, and wild plant foods that the Indians, it seemed, lazily lived off in an indolent existence, when John Muir wrote his glorious praise of California’s Central Valley with its endless meadows of wildflowers, they were actually looking at a sophisticated garden, lovingly tended for generations. According to the elders Anderson interviewed, “wilderness” was not a positive concept in Native culture; it meant land that was not well tended, land in which human beings were not exercising their duty to protect, enhance, and develop life. It is easy to see how the perception of indolent natives living in “virgin” wilderness facilitated intrusion onto their territory. After all, they were just inhabiting it; they weren’t developing it, they weren’t doing anything with it. It was going to waste. The ideology of the wild is of a piece with the ideology of conquest.

What looked to European settlers like untamed wilderness was actually the product of millennia of intentional human influence. Calling it wilderness, or “virgin territory,” gave them license to occupy it, cultivate it, “develop” it, and “improve” it.

This attitude is still wreaking its damage today in places like Brazil, where Amazonian tribes attempting to establish rights to their ancestral territory are required to prove the traditional occupancy of that territory.

The difficulty is that their mark on the land is not of a kind that the government can easily recognize. They did not establish permanent farms or dwellings. The ideology of “the wild” renders the mutuality of their relationship to the land invisible.

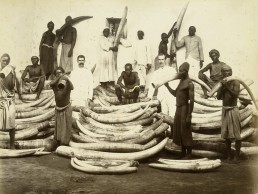

Modern conservationists might be excused for wanting to minimize human impact, since the kind of human impact we’ve seen in the industrial era makes the caring observer recoil in horror. We might be excused for promoting an ethic of “leave no trace.” We might be excused for envisioning a future where humanity retreats to bubble cities, space colonies, or a virtual reality, leaving nature behind to recover its former wholeness, relating to it as a spectacle or a venue for recreation, visiting it perhaps as zero- impact ghosts, observers but not participants.

Tending the Wild suggests a different vision, freeing us from the perceptions with which industrial society has imbued us. Instead of zero impact, it suggests positive impact. Instead of leave no trace, it suggests “leave a beautiful trace” or “leave a healing trace.” It suggests that we ask, “What is our proper role and function in service to the health, harmony, and evolution of this whole of which we are a part?”

We have potent gifts of hand and mind that take the form of technology and culture. These gifts are not meant for us alone. They are meant to serve the wholeness and evolution of Life.

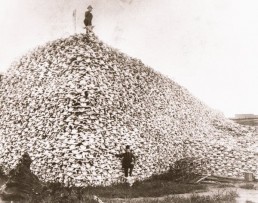

True, as a civilization we have not used our gifts in this way. Even pre- industrial peoples wreaked considerable havoc, contributing to the desertification of the Middle East and other areas, and to the disappearance of North and South America’s megafauna. The latter coincided with dramatic changes in the composition of vegetation: the extinction of mammoths, mastodons, and other megafauna led to forests replacing savannas in many parts of the continent, along with a steep decline in overall biodiversity 22 and nutrient availability.23 Perhaps it was through the tragedy of these extinctions that the newcomers to North America learned to pay special attention to preserving and expanding what remained of the continent’s biological wealth.

Just because someone is indigenous does not mean he or she, or her culture, knows how to live in mutually beneficial harmony with the earth. It is something each culture must learn. Furthermore, each level of developmental scale requires a new learning.

Extinctions of megafauna and other animals and plants regularly followed human settlement of new lands. Australia, the Americas, New Zealand, Madagascar, and Polynesia all experienced them, suggesting a kind of inevitability to anthropogenic ecocide, which has only accelerated along with our capacity to perpetrate it. Yet, in the end, people in all of these places eventually came into equilibrium with their lands. In most places, as the subsequent biological wealth of the Americas exemplifies, it was an abundant and biodiverse equilibrium. This suggests another possibility beyond Man the Destroyer—that we can learn from our mistakes, that we can mature in our gifts and turn them toward a different purpose.

If so, then we have a lot to learn from indigenous people who sustainably tended and enriched the lands and waters they called home. Sometimes this might entail learning from their actual methods, but more probably it is a matter of adopting the mentality that gave birth to those methods in the first place, since the environment of ten thousand or even five hundred years ago is probably lost forever. That mentality is the product of the worldview I call the Story of Interbeing, a story that unites the diverse mythologies of indigenous peoples. More practically, it means forging intimate, respectful relationships with nature in its specific, local embodiment. Through extended close observation and interaction with nature, we can begin to hear answers to questions like “What does the river need?” “What does the mountain want?” “What is the dream of the land?”

These are the kind of questions that may take long, intimate observation—scientific and otherwise—to answer. There is no sure formula to determine which land should be grazed with compact herds, and which land should be protected from grazing entirely. There is no sure formula to determine which exotic species should be controlled as an “invasive,” and which should be welcomed for their contribution to a new balance.

This latter question is reflected in the debate between restoration ecologists, who seek to reverse ecological damage and bring back native species, and the “new ecologists” who question the assumptions behind the concept of restoration. Science writer Janet Marinelli describes the divide:

At a time when restoration of forests and other ecosystems is increasingly essential, the dominant paradigm of restoration science has been shaken to its core. Restoration ecologists, for whom returning lands to their state before the arrival of Europeans on the continent is still the basic, if rarely stated, goal, have been at loggerheads with so-called new ecologists, who challenge the primacy of native species in conservation thinking and champion the “novel ecosystems” of native and exotic species that increasingly dominate the planet.24

This passage hints at an emerging synthesis between the two positions. Human intervention is obviously necessary to restore ecosystems—not necessarily to their former state, but to a state of health. Yet, neither is their former state an irrelevancy. Historical knowledge is useful in understanding the land’s needs, where they came from, and how to meet them. No general formula can tell us, for example, when an invasive species needs to be controlled, and when it is actually an agent of a damaged ecosystem coming back into balance.25

Neither “trusting nature” nor “restoring ecosystems” offers a reliable recipe for action. The question is not whether to participate, but how. Absent a recipe, we are left with place-specific, intimate observation and sincere inquiry informed by the understanding of the nonlinear, living nature of each ecological being. That’s how we gain the wisdom to know how to participate in regenerating the health of the places and planet we inhabit.

All of the regenerative practices I’ve described in this chapter partake in a common sponsoring idea. Earth is alive. What is alive, we can love. What we love, we wish to serve. When what we love is sick, we want to ease its suffering and serve its healing. The more deeply we know it, the better we can join its healing.

From Climate—A New Story by Charles Eisenstein. Published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2018 by Charles Eisenstein. Reprinted by permission of publisher.

Flipping the script on climate change, Eisenstein makes a case for a wholesale reimagining of the framing, tactics, and goals we employ in our journey to heal from ecological destruction

320 pages | Release Date: 2018-09-18

…a conversation with Charles Eisenstein

Kosmos | What does our depletion of the planet’s gifts have to say about our modern addictions and habits of consumption? What are some historic ‘seeds’ of consumption that are contributing to our converging crises?

Charles | I believe that addiction results from trying to meet a need with something that can only assuage the discomfort of the unmet need, but cannot satisfy it. The current industrial system is good at satisfying — to repletion and beyond — our quantifiable needs (equitable distribution is another matter). Meanwhile, essential qualitative needs go unmet. No amount of possessions, or BTUs per capita, or floor space per capita, or gigabytes of internet connectivity, can satisfy our needs for intimacy, connection, authenticity, aesthetic pleasure, community, meaning, or belonging. It is the lack of these things that drives society to acquire more and more of their substitutes.

An isolated, alienated individual disconnected from meaningful participation in a larger purpose is bound to be a good consumer, seeking to fill the void left by the disintegration of community and meaning.

What is the cause of this disintegration? In part, it is the economic system, which depends for its functioning on endless growth. Growth means growth in goods and services in the money economy. That is the fundamental basis of credit and money creation. So we have an endless expansion of the money realm, and consequently a reduction of more and more of life to money. It is almost the reverse of what is commonly assumed: rather than greed or addiction driving economic growth; it is mostly that economic growth drives greed and addiction. Economic growth requires the stripmining of community and nature; the conversion of relationships into services and nature into commodities.

The conversion of quality to quantity is inevitable when more and more things are mapped onto a linear scale called “value.” The result is a pervasive poverty that afflicts rich and poor alike. The rich can at least maintain an illusion of wealth by purchasing substitutes for what has been lost.

Kosmos | What is mindful consumption? Is it possible to become loving consumers?

Charles | Mindful consumption means developing awareness of the causes and effects embodied in what we consume. It means seeing the object of consumption not as a separate object, but in all its relationships. The current system encourages us to see products in isolation — there it is on the shelf, all packaged up. Its source, the labor and natural resources that went into it, the harm or benefit that its production caused… none of these are visible. Mindful consumption simply seeks to make them visible.

In ancient economies all these things were already visible, because production was not so distant nor the division of labor so elaborate. The provenance of any object or any meal was obvious. That’s not the case with standardized products like, say, a cell phone, produced through a global coordination of resources, labor, and creativity. To be mindful then, we need information about supply chains, production practices, ecological effects, and so on.

I do not advocate trying to translate this information into a formula or ethical code, for example by calculating your carbon footprint and making decisions by the numbers. I advocate a kind of self-trust that says, “As my awareness of causes and consequences grows, I trust that I will naturally make decisions that serve life.”

Kosmos | In terms of activism, is anger or rage ever helpful? Why or why not?

Charles | Anger creates movement and gives expression to stuck energy. The problem is that anger is so easily diverted onto convenient, false targets. We want to find someone to be angry at. However, those people or institutions may merely be expressing symptoms of a deeper problem. For example, a lot of people direct their rage at Donald Trump. That’s quite understandable, but let’s suppose we tear him down. The anger is appeased and, if we were driven by anger, we put down the protest signs and go home, thinking, “Problem solved.” Yet on some level we know that Donald Trump, or anyone you hate, is an expression of deeper conditions.

If I were an evil overlord seeking to maintain the status quo, I would set up despicable leaders to absorb the energy of discontent and direct it away from system change.

I am not saying, “You shouldn’t be angry.” It isn’t about should or shouldn’t. It is simply about seeing the truth. Recently a friend of mine discovered his wife had been lying to him for years, maintaining a web of deception, gaslighting him. His anger was intense. His friends were angry too. Yet when we ask, “Why did she do that?” and discover her childhood trauma, it is hard to stay angry. We understand, “If I’d been abused like that, I too might be manipulative and controlling just like her.”

The question is, do you want to win a fight? Or do you want a healed Earth? Do you want victory over the White supremacists, or do you want to end racism? Do you want to dance in triumph over your defeated enemy, or do you want the wars to stop? This is not about anger being bad, and it is not about suppressing anger. It is about dissociating the primal motive energy of anger from the narratives that invite us to set up and battle an enemy.

In our society, broad acceptance of that invitation has brought intense political polarization. When people look at every public figure through the lens of “Which side is he on?” there is no possibility of engaging any idea outside the continuum defined by the standard poles. In my climate book, I do my best to disarm this tendency by describing the normative spectrum of opinion and identifying the problematic hidden assumptions all sides share. But still, people try to figure out which side I’m on. But because I refuse to offer up a target for their anger, I’m afraid everyone will think I’m not on their side. In a way they are right. Under current circumstances, I believe that grief and not anger is the best guide moving forward.

Kosmos | One of my favorite lines in the book is: If the world’s illnesses could be healed within the confines of the Story of Separation, then we could safely divorce spirituality from activism. Since they can’t and we can’t – what kind of spirituality is most needed now? Are certain forms of activism more helpful than others?

Charles | Spirituality can mean different things to different people. In this context, I meant it to refer to those phenomena and experiences that do not fit into materiality, as conceived by science and the dominant force-based theory of causality. In short, we are attempting the impossible. The illnesses are incurable given what we as a society have accepted as real. Therefore, we need to reach for a larger conception of what is real, who we are, and how change happens. In the book, I talk about people whose bodies have healed from supposedly incurable medical conditions. I ask, “What is the equivalent for the social body, the ecological body, the body politic?”

As to what kind of spirituality is needed now, it is to take seriously the experiences and perceptions that we have relegated to the “spiritual” realm and to reincorporate them into the material. It is to embrace non-quantitative ways of knowing. It is to move past the old mechanistic view that saw human beings as the only full subjects in the world. It is to explore the universal indigenous perception that the world, and everything in it, bears consciousness, beingness, and some form of intelligence and purpose. Then we no longer need to impose our own intelligence on the world, but we seek instead to listen for and participate in something greater.

Any activism informed by this kind of spirituality will help change the ground conditions that will determine the life or death of this planet.

References

21. Anderson (2006).

22. Barnosky et al. (2016).

23. Doughty et al. (2013).

24. Marinelli (2017).

25. For a critical discussion of the complexities of invasive species management, see Tao Orion’s book Beyond the War on Invasive Species. Often the efforts to control invasive species do more harm than good.

This article resonates strongly for me. I have just begun to read a novel by Annie Proulx entitled “Barkskins”. It is the story of the demise of the forests . The first part talks about a man from France who has come to New France to colonize. His contempt for the trees is appalling and I believe it exemplifies how the Europeans viewed nature. Eisenstein captures the kind of thinking that has allowed the human species to get where it is. Thank you for such insightful and informative articles such as this.

I absolutely love this as I love all of Charles’s writings. I’m myself in the process of trying to return to my native roots/ land of Colombia. However, after living here so long in the U.S. I don’t have much family or community in Colombia. I’m not sure how to proceed forward in my life but I know I am part of the ecosystem there and I belong there…surely not here. But then how to proceed with very little resources and a child in tow is beside me…plus everybody around me telling me how horrible of an idea it is. If anyone has suggestions/guidance that would be greatly appreciated. Thank you!